Leadership and Community Change Workbook

advertisement

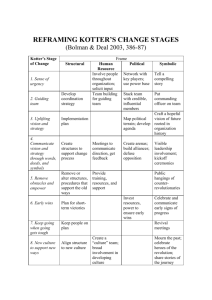

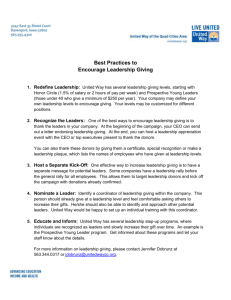

As leaders and change agents in the communities we serve, we often have noble goals and lofty visions, but in practice we are not focused and concrete enough to make progress that is tangible and contagious, and as a result we often cannot get any traction toward our goals. Our purpose with this workbook is to introduce a formula for making progress with community change in hopes that it inspires a more intentional approach to leadership for change, particularly on the intractable and elusive larger goals that are vexing our leaders year to year – “reducing poverty,” “building a culture of health,” or “nurturing the entrepreneurial spirit.” The seven step formula we introduce here is inspired by the work of John Kotter at the Harvard Business School who helps frame the issue with his assertion that “Management is about coping with complexity and leadership, by contrast, is about coping with change,” and Chip and Dan Heath in their volume Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. The steps are illustrated with examples from legendary nonprofit and public sector case studies of leadership and change, notably: William Bratton and the Broken Windows Theory of Policing in New York City Charles Best and the online teacher's supply portal Donors Choose Paul Levy and institutional change at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center You may find it useful to access these linked cases and read through them prior to stepping through this workbook. Briefly stated, the seven steps that comprise our formula regarding leadership for change are: 1. URGENCY – Focus on a problem with a sense of urgency or one that mobilizes by stirring outrage. 2. SMALL SCALE – Pick a small scale solution that people can relate to and replicate. 3. VISION – Find the feeling by creating and communicating a compelling vision. 4. SCRIPT – Script the critical moves by telling people exactly what to do and empowering them in creative ways. 5. CELEBRATE WINS – Point to the destination and create and celebrate wins or arrivals at key waystations. 6. MULTIPLY – Multiply the gains. 7. BOTTLE IT – Institutionalize to preserve. We will now examine each step in detail to introduce a promising and time-tested path for leadership that leads to change. 2 Because it’s hard to motivate concern and action or even prioritize the issue as something to think about if the consequences of inaction aren’t dire, the first practical step is to engage people emotionally in the issue. This can be done by selecting a problem that pushes the public’s panic buttons, as was done in New York City in the mid-1990s when the city had an out of control crime rate and fear was a palpable emotion on the streets and throughout the boroughs. With crime running rampant, it did not take much for the city’s leaders and the public to line up behind this issue. With the focus on organizational change, Paul Levy, the new CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, was able to harness the full attention and energy of the employees and Trustees by facing down a financial crisis that threatened the viability of the institution. Sometimes, there is nothing like imminent joblessness to really get people’s attention. Even if it’s not the life-threatening or job-threatening degree of danger, emotions can be engaged by stirring a sense of outrage – the moral indignation that may rise from the feeling that in our society – or in our community – we just cannot tolerate a condition like this – we can and must do better. This is the situation Charles Best confronted as a new teacher in the New York City public schools where there was no public budget for consumable supplies in the 3 classroom. Teachers were buying all the supplies they needed out of their own pockets. The willingness to stand up for change was ignited by stirring the sense that civilized communities that have their priorities straight simply do not act this way. So the sum up… to get attention and the degree of focus that leads to action, pick an issue that is urgent, dire, or one that stirs up emotional outrage. People have to have the fire in their belly to act. One of the enduring problems associated with “big goal” change – let’s say reducing poverty in the community – is that even though it may pass the emotional or urgency test, it is often so big and multi-faceted that people feel defeated just trying to get their arms around it. It is too big, too overwhelming to do anything about. You don’t know where to start, and your locus of control is diminished because there are so many economic, social, and educational factors that feed the growth of the problem. So picking a small scale starting place that frames the problem as one that can be solved, at least partially, is a critical second step. This was the operating principle behind Bratton’s selection of petty but visible crime as the focus of the NYC Police Department’s initial very public crackdown on crime in and across New York City. By targeting perpetrators of car break-ins, “squeegee men” that shake down drivers at traffic lights, and turnstile jumpers on the city’s transit system, the focus on very public, very 4 visible, and very pervasive types of crimes set the stage for a dramatic intervention that could play out in the public eye and in the press and broadcast media. In drawing attention to the crisis around school supplies and its effect on quality education and teacher morale, Best started with the focus on a single classroom – his own, then grew the issue school-wide – then district-wide, but to gain any traction at all, the power of the solution first had to be demonstrated small scale, then replicated and grown. Levy, searching for starting place for his turn-around that would both give the medical center some locus of control and fully engage the medical staff as a point of pride, chose to focus on increasing quality of care and improving patient satisfaction. These were the tools the hospitals could use to leverage systemic change. In sum, pointing to a tangible starting place that people can put their arms around and embrace is essential. This in turn advances the locus of control issue – the degree to which the leader can control or own the issue and thereby direct the success of the outcome. In the parlance of the Heath brothers in Switch, the imperative is to “shrink the change.” 5 Kotter’s work on leadership and change drills down on the assertion that leadership involves setting direction, but beyond that requires capturing stakeholders with a vision. He notes: “In every successful transformation effort that I have seen, the guiding coalition develops a picture of the future that is relatively easy to communicate and appeals to customers, (stake)holders, and employees…. A vision says something that helps clarify the direction in which an organization needs to move.” Chip and Dan Heath refer to the vision thing as “finding the feeling,” and in their metaphorical dance between the elephant and the rider that plays out throughout their entertaining volume, both of which are essential for engineer change successfully, the elephant gets powerfully and emotionally motivated to move as a result of the feeling that is connected to the vision. In our example cases, this vision plays out in distinct ways. To address petty street-level crime in New York City, Bratton had to empower officers to act and did this by turning the culture of management upside down- letting officers and precinct captains have much more control over their priorities, responses, and crime-fighting actions. This empowerment was successful in the 1990s but has since been widely discredited as the many incidents of police abuse of power in recent years have opened up the ugly dark side of officer empowerment to public inspection. At the time, this vision of an alive, active, and responsive police force, was a welcome vision and one that drove both departmental management reform and a huge reduction in the crime rate. For Charles Best, showcasing the vision of the online teacher’s supply portal – Donors Choose – powered by the donations of caring individuals who wanted to help teachers and students, was the way to connect teacher need with philanthropy through technology – a compelling vision of how this could be done on a huge scale in the future. At the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the vision of the future was one where high quality care, better patient outcomes, and a high degree of patient satisfaction transformed the heretofore dysfunctional hospitals into a major healthcare competitor. This vision was one that was created simply – first by Levy the CEO being transparent and accountable in a blog that grew to be increasingly visible, then by the power of the staff and Trustees aligning their personal and professional pride behind the compelling vision of a highly-regarded medical center that was loved by its patients. In 2007, Trustees approved two long term goals that created anchors for this vision- to eliminate preventable harm by January 1, 2012 and to achieve patient satisfaction scores that place Beth Israel Deaconess among the top 2% of hospitals also by January 1, 2012. The vision in each case is that of a responsive, caring system that has been created through a culture change – in management, in professional practice, or through donors using technology to drive change – any and all of which enabled a larger groups of stakeholders to “find the feeling” embedded in the vision and harness the energy to move forward with the change process. But how to move forward and what – exactly - to do? That is the next question. 6 Once people are energized by the vision and are listening to you, the next step is to tell them exactly what to do – or as the Heaths say, “to script the critical moves.” Our case studies offer a range of responses that shed light on the various ways this can be done. Paul Levy led the hospitals in following perhaps the most fundamental of these scripts. His objective was to make staff proud of the outcomes and to use the sense of achievement to drive further improvement. His vehicle for this was to introduce annual operating plans. The case study narrative indicates: “Annual operating plans enabled managers to maintain focus. Each operating plan contained three or four major goals, the first of which would be focused on quality and safety. The second goal would focus on patient satisfaction and the third would be a financial goal.” For their part Charles Best and Donors Choose were confronted by a classic chicken and egg management dilemma: Donors would come to the website only if there were a number of exciting projects posted, while teachers would only take time to post projects and needs if there were numerous donors visiting the site. To address this, Best grew initial success by guiding his New York City colleagues to post exciting projects while at the same time tapping personal and family networks to fund the projects and thereby demonstrate tremendous initial success on his initial city-wide scale. 7 Meanwhile, elsewhere in New York City, Police Commissioner Bratton was scripting critical moves for his newly empowered police officers who were suddenly proving to be a force in neighborhoods across all the boroughs. Among the particulars in the script: Take part in community meetings and become active with neighborhood groups; be visible on the street outside the confines of a vehicle by biking and walking; and focus on the issues that matter to people – look at the quality of life and work on it with residents. In an environment that is filled with the uncertainty that a change process brings about, Kotter emphasizes the importance of leaders communicating constantly and through all available channels. But what leaders say is important, too. Chip and Dan Heath remind us that in times of change, autopilot choices don’t work anymore because change brings new choices that create uncertainty and uncertainty can lead to paralysis that will result in continuing with the known comfort of the status quo. In their words: “Many leaders pride themselves on setting high-level direction… It’s true that a compelling vision is critical, but it’s not enough. Big-picture, hands-off leadership isn’t likely to work in a change situation because the hardest part of change – the paralyzing part – is precisely in the details… The Rider has to be jarred out of introspection, out of analysis. He needs a script that explains how to act and that’s why the successes we’ve seen have involved such crisp direction.” 8 To generate momentum toward the change goal and to create and sustain a sense of progress that sweeps stakeholders along, it is important to point to the destination but at the same time celebrate wins when short-term victories are achieved and waystations have been touched. Kotter writes: “Real transformation takes time and a renewal effort risks losing momentum if there are not short-term goals to meet and celebrate. Most people won’t go on the long march unless they see compelling evidence in the first 12 to 24 months that the journey is producing expected results. Without short-term wins, too many people give up or actively join the ranks of those people who have been resisting change.” Many students of business culture are familiar with the acronym BHAG – Big Hairy Audacious Goal – and as we’ve seen, those can sometimes lead to paralysis unless the interim steps are 9 broken down into tangible, manageable parts. The Heaths introduce the image of the “destination postcard” – a vivid picture from the near-term future that shows what could be possible. “What’s essential, though,” they conclude, “is to marry your long-term goal with short-term critical moves… You have to back up your destination postcard with a good behavioral script.” In our illustrative cases, this is done is a variety of ways. In revolutionizing policing and reducing crime in New York City, Bratton introduced the power of big data at the precinct and station house level and got the rank and file excited about the tangible statistical drops in crime that the department’s new data systems were reporting. Tracking and celebrating these interim wins offered multiple opportunities for celebration every month. Levy at BID followed a similar path. The annual operating plans drove an improvement in performance that was contagious in the system and gains in quality and patient satisfaction could be tracked continuously and celebrated internally as trend lines on new dashboards moved steadily in a positive direction. As the hospital’s new commitment to transparency moved this data onto the CEO’s blog and the hospital’s website, a larger audience began to notice and follow the change with interest. Having experienced initial success in the New York City public schools with Donors Choose, Charles Best was still captivated by the destination postcard that promised nation-wide applicability. The next steps in that journey were able to be taken thanks to an appearance on the very popular and credibility-enhancing Oprah show where Best trumpeted the success in New York. This opened the door to his next waystation – the opportunity to go statewide with Donors Choose in North Carolina. In short, because the change process can often be a long one, the sense of urgency can dissipate and the process can stall out. Finding compelling ways to continue to point to the final destination while creating and celebrating opportunities for short-term wins goes a long way toward sustaining momentum and leaders grind away at the change process. 10 With initial victories being celebrated at waystations along the route, leaders of successful change efforts look for ways to multiply those early victories to create unstoppable momentum as well as to harness the energy and credibility associated with early wins to tackle needed system and structural changes and to get the right people on the bus for the balance of the journey. The leaders in our illustrative cases each harness different allies that become their multipliers. Bratton had achieved success on several levels – culturally he had upended the department and empowered officers at the street level and he introduced big data to track and celebrate gains. To translate this success to the next level and galvanize the support of the entire city, he next turned to marketing and public relations and by becoming a fixture in the press and on televised news, he became a hero who overshadowed Mayor Giuiliani and sets standards for policing nationwide. Charles Best, meanwhile, had the good fortune to translate the success of his statewide effort with Donors Choose in North Carolina into a multi-million dollar scale-up investment by Silicon Valley donors to take Donors Choose to a national scale. This led to the building of a more massive infrastructure, a fulfillment network, and the huge management challenge associated with the coordination and development of an ever-growing network of schools, teachers, and donors. Paul Levy at Beth Israel Deaconess continued the active sharing of data by putting dashboards up in all the hospital units, undertaking a campaign to reinforce a culture of caring and listening, and continue the philosophy of transparency that even made great leaps forward as a result of 11 owning up to a serious surgical error that still advanced the public perception that it was truly a hospital on the move. In each of these settings, there is much at this level that grows through the contagion factor especially in efforts that are powered by the media or multi-million dollar investments. But as Kotter reminds us, it is also attributable to the efforts of leaders to tie the gains being made to the new approaches, behaviors, and attitudes exhibited by everyone along the way. The leaders connect the dots so that the change process is visible and understandable for all. Arguably the hardest part of change is making it stick, having it become a permanent part of organizational culture or the larger life of the community. Kotter notes: “In the final analysis, change sticks when it becomes “the way we do things around here,” when it seeps into the bloodstream of the corporate body. Until new behaviors are rooted in social norms and shared values, they are subject to degradation as soon as the pressure for change is removed.” In our cases, the institutionalization process played out along different lines. Bratton and the New York City police made tremendous strides in changing the culture of policing, reducing crime, managing with the help of big data, and galvanizing the city with the help of a favorable media and public relations blitz. After two years, the success proved to be too much for the 12 Mayor who then removed Bratton, but the changes had been cemented in place by then and even under new command crime rates continued to fall for the next five years in New York. Over time, the downside of officer empowerment exploded in tragic ways so that now this movement is somewhat discredited, but in the 1990s Bratton’s change was seen as visionary and heroic. At Beth Israel Deaconess, Levy’s basic approach was “finding out what you’re good at and doing more of it.” His commitment to transparency and the steadfastness around quality care and patient satisfaction not only helped the hospitals achieve their January 1, 2012 big goals, it drew over 10,000 visitors a day to learn from the stories on the institution’s website. BID’s Director of Health Care Quality noted: “We have moved beyond quality simply being a compliance issue. It’s been important to have a consolidated group of clinicians who can help integrate the quality instructions with the clinical work. We have been able to introduce change that is effective. People don’t want change but they will tolerate it if it leads to improvement. The focus on safety and transparency is now established. It has become a central plank in helping us continue our tradition of caring and excellence in delivery of care.” Donors Choose, meanwhile, still seems to be a work in progress, largely brought on by the difficulty of finding a funding mechanism that can sustain the huge organizational infrastructure that was built with the Silicon Valley investment. Best has toyed with adding a “fulfillment fee” to each donation and has strengthened efforts to obtain support from foundations coast to coast. Meanwhile, the specter of mission creep has also popped up with the idea of using Donors Choose as a vehicle to pursue larger goals related to systemic reform of public education. These tensions play out through the organization to this day. In the final analysis, having the visionary leader stay in place throughout the change process is clearly useful, but as we’ve seen, it is not necessarily essential. Bratton departed but the benefits of a changed culture were carried on by successors. Levy saw himself as a change agent from the beginning and found that his background in management rather than medicine was an asset. An MD is again in charge at BID today, and the changes wrought by Levy have stayed because they became baked into organizational culture. Charles Best, of course, no longer teaches in the classroom, having committed to growing and managing Donors Choose. There to nurture the vision and continue to point to the destination, Donors Choose can still be considered a work in progress. 13 Since we have cited “poverty reduction” as one of the big hairy audacious goals that has been established for our community, it may be useful to try and apply the seven steps involved in leadership to community change to this compelling issue. Here is how it might take shape: Steps 1. URGENCY – Focus on a problem with a sense of urgency or one that stirs a sense of outrage. 2. SMALL SCALE – Pick a small scale solution that people can relate to and replicate with a high locus of control. 3. VISION – Find the feeling by creating and communicating a compelling vision. 4. SCRIPT – Script the critical moves by telling people exactly what to do. Implications Poverty rate is growing locally, becoming entrenched with downside attributes like crime, violence, drugs, and blight that have never been seen before in this region; a moral affront. Solutions pursued are often out of the control of those most affected. Launch a community movement to create more start-up small and micro-businesses that can start as small income supplements and grow. As they do it will increase income, build pride and a sense of hope, and give a sense of control for those emerging from poverty. Empowerment: “I’m in charge of my own destiny for once.” Get entrepreneurship training widely established and accessible. Develop micro-financing with CDFIs, investors, foundations, and government. Offer coaching and mentoring. “Small is beautiful.” 14 5. CELEBRATE WINS – Point to the destination and create and celebrate short-term wins and waystations. 6. MULTIPLY – Multiply the gains 7. BOTTLE IT – Institutionalize the culture. Share success stories. Celebrate intermediate milestones like incorporation, financing, first profit, etc. Push success stories out through social and mass media; establish ongoing entrepreneurship incubators at community centers. Enlist successful alumni as coaches; keep leaders and financing in place; maintain a peer support system to sustain progress for the long haul. Take what you’ve gleaned from these steps and apply it to your own change goal. To download a Word document that will expand as you enter your thoughts Click here. Steps 1. URGENCY – Focus on a problem with a sense of urgency or one that stirs a sense of outrage. Implications 2. SMALL SCALE – Pick a small scale solution that people can relate to and replicate with a high locus of control. 3. VISION – Find the feeling by creating and communicating a compelling vision. 4. SCRIPT – Script the critical moves by telling people exactly what to do. 5. CELEBRATE WINS – Point to the destination and create and celebrate short-term wins and waystations. 6. MULTIPLY – Multiply the gains 15 7. BOTTLE IT – Institutionalize the culture. We would appreciate your feedback on the utility of this leadership and change workbook. Click here. Chip Heath and Dan Heath, Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York: Broadway Books, 2010. John P. Kotter, “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail” Harvard Business Review On Point Winter, 2014. pp. 30-37. John P. Kotter, “What Leaders Really Do,” Harvard Business Review On Point Fall, 2014. pp. 5262. 16