Historical Context on Movements

advertisement

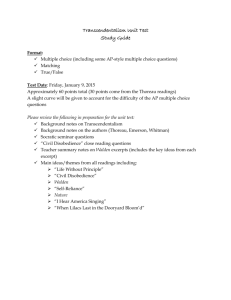

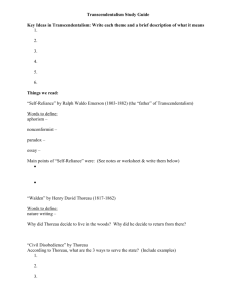

Background Information on the American Revolution, Transcendentalism, and the Civil Rights Movement American Revolution The American Revolution was a political upheaval that took place between 1765 and 1783 (open warfare occurring, 1775–83) during which colonists in the 13 American colonies rejected the British monarchy and aristocracy, overthrew the authority of Great Britain, and founded the United State of America. In 1775, Jefferson was elected to the Continental Congress. He drafted the Declaration of Independence, signed on July 4, 1776. Historians differ on whether the American Revolution was primarily an intellectual movement or an economic dispute. It has been said that the American Revolution was a tax revolt in patriotic dress. Either an Enlightenment battle over natural rights and citizenship, or an expression of resentment by merchant interests, by the mid 1760’s, differences between Britain and the colonies were exacerbated by a series of economic disputes. At issue: trade and taxes and duties on goods that were imposed on the colonies to pay for the cost of Empire. Britain was deeply in debt. Commercialism was the accepted custom, and as such, the thought was that the colonies should contribute more to the common security of the realm. Aside from noting in detail the grievances, or “usurpations” of Britain, the Declaration reflects the shift in ideas of representation and democratic legitimacy taking place at the time. Benjamin Franklin and John Adams assisted the 33-year-old Jefferson in writing the Declaration. In the previous months, at least ninety local declarations of independence were circulating around the colonies. Jefferson relied on them, as well as the social contract theory of John Locke in his writing. Social contract theory: the view that persons' moral and/or political obligations are dependent upon a contract or agreement among them to form the society in which they live. Transcendentalism People, men and women equally, have knowledge about themselves and the world around them that "transcends" or goes beyond what they can see, hear, taste, touch, or feel.This knowledge comes through intuition and imagination not through logic or the senses. People can trust themselves to be their own authority on what is right. A TRANSCENDENTALIST is a person who accepts these ideas not as religious beliefs but as a way of understanding life relationships. The individuals most closely associated with this new way of thinking were connected loosely through a group known as THE TRANSCENDENTAL CLUB, which met in the Boston home of GEORGE RIPLEY. Their chief publication was a periodical called The Dial, edited by Margaret Fuller, a political radical and feminist whose book Women of the Nineteenth Century was among the most famous of its time. The club had many extraordinary thinkers, but accorded the leadership position to RALPH WALDO EMERSON. The Transcendental Club was associated with colorful members between 1836 and 1860. Among these were literary figures NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, and WALT WHITMAN. But the most interesting character by far was HENRY DAVID THOREAU, who tried to put transcendentalism into practice. A great admirer of Emerson, Thoreau nevertheless was his own man — described variously as strange, gentle, fanatic, selfish, a dreamer, a stubborn individualist. For two years, Thoreau carried out the most famous experiment in self-reliance when he went to WALDEN POND, built a hut, and tried to live self-sufficiently without the trappings or interference of society. The following was his motivation for writing “Civil Disobedience”--Henry D. Thoreau was arrested and imprisoned in Concord for one night in 1846 for nonpayment of his poll tax. This act of defiance was a protest against slavery and against the Mexican War, which Thoreau and other abolitionists regarded as a means to expand the slave territory. As a group, the transcendentalists led the celebration of the American experiment as one of individualism and self-reliance. They took progressive stands on women's rights, abolition, reform, and education. They criticized government, organized religion, laws, social institutions, and creeping industrialization. They created an American "state of mind" in which imagination was better than reason, creativity was better than theory, and action was better than contemplation. And they had faith that all would be well because humans could transcend limits and reach astonishing heights. Civil Rights Movement Nearly 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation (1863), African Americans in Southern states still inhabited a starkly unequal world of disenfranchisement, segregation, and various forms of oppression, including race-inspired violence. “Jim Crow” laws at the local and state levels barred them from classrooms and bathrooms, from theaters and train cars, from juries and legislatures. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine that formed the basis for state-sanctioned discrimination, drawing national and international attention to African Americans’ plight. In the turbulent decade and a half that followed, civil rights activists used nonviolent protest and civil disobedience to bring about change, and the federal government made legislative headway with initiatives such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Many leaders from within the African American community and beyond rose to prominence during the Civil Rights era, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Andrew Goodman and others. They risked—and sometimes lost—their lives in the name of freedom and equality. King and nearly 50 other protestors and civil rights leaders had been arrested after leading a Good Friday demonstration as part of the Birmingham Campaign, designed to bring national attention to the brutal, racist treatment suffered by blacks in one of the most segregated cities in America—Birmingham, Alabama. For months, an organized boycott of the city’s white-owned-and-operated businesses had failed to achieve any substantive results, leaving King and others convinced they had no other options but more direct actions, ignoring a recently passed ordinance that prohibited public gathering without an official permit. For King, this arrest—his 13th—would become one of the most important of his career. Thrown into solitary confinement, King was initially denied access to his lawyers or allowed to contact his wife, until President John F. Kennedy was urged to intervene on his behalf. As previously agreed upon, King was not immediately bailed out of jail by his supporters, having instead agreed to a longer stay in jail to draw additional attention to the plight of black Americans.