HOW THE NORTH WAS BUILT – Juillet 2013 ITV Press Center

advertisement

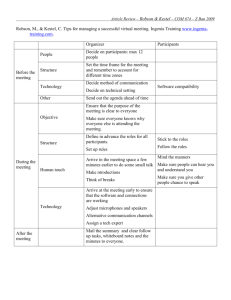

HOW THE NORTH WAS BUILT – Juillet 2013 ITV Press Center Episode: 1/2 Diffusion: Mardi 09 Juillet 2013 Chaîne: ITV Publication: Mardi 25 Juin 2013 Production: Silver River “Recently I moved back to the north, after spending many years down south and other places. There is something very special about this location, I love the landscape, the cities and of course, the people. I want to see how people in this rugged land dug the coal, laid the railways, built the ships that powered an empire, and made this the greatest industrial nation on earth. The industries might have gone but the people, their values and sense of belonging, they’re still here, as strong as ever.” Robson Green has moved back home to the north and immerses himself in telling the incredible story of how industry has shaped both a place and its people. This brand new, two-part series celebrates the rugged northern landscape and how the sheer hard work of the people in the north contributed to the industrial revolution which changed the face of the world. The north is where Robson’s family has its roots and is steeped in industrial heritage. Robson’s father was a fourth generation miner in the pits of Dudley, which towered over the houses where he was brought up. The story of how the north was built is intimately connected with Robson’s own family history. The mining of coal propelled Britain onto the world stage as an industrial giant and Robson begins by exploring the history of mining in the north whilst looking back over his own family history. Visiting his home town Robson says: “This is where I grew up. It’s a small mining village a few miles north of Newcastle called Dudley. My father was a miner. As was his father. As was his father before him. I remember waking up every morning in my bedroom and seeing the pit heads that surrounded the village.” Robson gathers together members of his own family to talk about their memories of the mining community and life back then. His Uncle Gordon remembers: “I left school on the Thursday and started at the pit on the Tuesday. That’s where the money was then. You could make some decent money at the pit.” In the early Victorian era, whole families could be found working down the pit. This was outlawed by the Mines Act in 1842 but women and children continued to play a key role in the economy of mining villages. Women ran the home, keeping a fire going and running hot baths for their husbands and sons who could all be working different shifts and spending eight hours a day underground and filthy. Robson investigates the rumour that mine owners sought to control the lives of their workers. Curator Jonathon Kinleysides says: “The mine owners would often pay the miners in tokens rather than cash. And those tokens could only be redeemed at the mine owner’s shop.” He also joins former miner Andy Smith underground in a pit face to experience the conditions faced by his own father and generations before. Once they have reached the bottom of the pit, Andy explains the dangers the miners faced on a daily basis: “Roof fall, gases, in rush of water, flooding. They were main ones and they're still prevalent today but they're just more under control now.” Robson also explores what life was like away from work and how a new culture evolved around industrial life, from working men's clubs, pubs, and holidays to music to sport, education and politics. Robson says: “I remember my dad coming home from a shift. He would tend his allotment. Growing his prize winning flowers. Or he would be practising one of the great loves of his life: ballroom dancing. My granddad loved racing pigeons. There was a life away from work. A life of aspiration, education, and being creative.” He meets former miner and pigeon racer Dave Turnton to find out more about the connection between mining and pigeon racing. Dave says: “When I first started at Hamsworth pit in ‘62 there were loads of miners got pigeons then and I think it’s the great outdoors. It sounds silly that somebody who works down (the) pit likes (the) outdoors. And hobbies like fishing, pigeon flying, whippet racing, gardening and having allotments. All outdoors because when you spent seven and half hours underground (you) didn’t see sunlight. You didn’t want to go and get cooped up in (the) house.” Robson moves on to Lancashire where the famously damp climate was perfect for the production of cotton. Cotton was to put Britain at the centre of world trade. What happened in the mills of Burnley, Blackburn, Bury and Oldham shaped the economy of the West Indies, the United States, India, Africa and the Far East. Manchester historian Anne Beswick explains to Robson the importance of the industrial revolution: “For the first time in history, an ordinary working man could make money without having inherited land. Before that you were aristocracy or you were, ‘the rest’.” The cotton mills were a punishing place to work, with 13 hour shifts, six days a week in dusty conditions and soaring temperatures. Robson says: “Well, my mum and dad never wanted me to go down the mine but I can't imagine parents at that time wanting their children to come into a place like this.” Robson then explores how a revolution in transport would change the face of the landscape, with the introduction of the railways. In 1830 there were only a few dozen railways in the country. By 1851, 6800 miles of railway track had been laid. Robson enjoys the experience of driving a steam train himself and says: “No innovation during the industrial revolution captured the public’s imagination as much as the railway. We’re still fascinated with steam trains today but back then in the early 19th century, these machines changed the face of the North, in ways we just can't comprehend today.” The railways didn’t just move goods, they also moved people. Robson meets historian Russell Hollowood to discover the impact of the trains on people’s lives. Russell says: “Before the railways, everything moves at the speed of a horse or a narrow boat on a canal. The railways break all those barriers. Suddenly someone can go from Liverpool to Manchester and back inside a day and have a meeting. Before the world of the railways people didn’t think so much of time in terms of seconds, minutes or even hours. It was morning, or afternoon, or the day. Now you're in a world where people can check a timetable and say, ‘I can be with you in 20 minutes.’” The introduction of the railways changed the lives of workers. Every year they would get a week’s unpaid leave while the machinery was maintained and would all head to one place, Blackpool. The modern day holiday was born. Historian Robert Poole explains to Robson what Blackpool meant to the workers: “It’s hard for us to imagine what a liberation it was to go to the seaside for a week. They'd be working 12 hours a day. Working six days a week. But for one week in the year they don’t have to do that. They feel physically different.” Concluding the episode, Robson reflects on what he has learnt about the great industries of coal, cotton, steam-power and the railways, the incredible impact they had worldwide and what this meant for the infamous northern character. Episode: 2/2 Diffusion: Mardi 16 Juillet 2013 Chaîne: ITV Publication: Jeudi 04 Juillet 2013 Production: Silver River 2 Robson Green has moved back home to the north and immerses himself in telling the incredible story of how industry has shaped both a place and its people. This brand new, two-part series celebrates the rugged northern landscape and how the sheer hard work of the people in the north contributed to the industrial revolution, which changed the face of the world. In episode two, Robson finds out how iron, steel and shipbuilding shaped the north, in the second wave of the industrial revolution. The growth of the railways created an insatiable demand for metals and the iron and steel produced in Sheffield, changed the face of the North beyond recognition. Smelting still takes place in Sheffield today and Robson visits a local factory. Robson says: “Every instinct in my body is telling me to stay away from this environment. You really don’t appreciate the noise, but most of all the temperature. I think I’ve given myself a suntan these last ten minutes.” During the industrial revolution cities like Newcastle and Sheffield grew at lightning speed and basic services such as housing and sanitation, struggled to keep up with the population boom. However, one institution kept up with these incredible changes, and that was the pub. The Beer Act of 1830 allowed people to sell beer from their own homes. Within eight years of the act being passed 46,000 beer houses had opened and the pub had become an indispensable part of Northern working life. Robson meets historian Bill Lancaster who explains how the pub was a community for men: “My grandmother used to talk of Sundays when all the men would flock down to the pub Sunday lunchtime and the women stayed home and cooked the dinner. Women would sit in the back lanes peeling potatoes and one of the women had gone down to the pub and come back with a bucket with beer. So they had these buckets of potato peelings going in and they’d also have cups on the floor. They could pick their cup up and dip it in the bucket and drink beer.” Pubs were the heart of the new industrial communities and sponsored many activities including the one sport which would come to dominate the north, football. Many famous teams began life as a pub team, after Victorian publicans realised that football was good for business. Links between the coal mines and the football field have always been strong and Robson meets Jack Charlton to discuss his cousin, all time great, Jackie Milburn. Jack says: “Jack used to take us. He’d take us in and sit us at the front, me and our Bob. There was no cricket. There was no rugby. There was but nobody ever went to see them. Football was the game in Northumberland.” Sheffield United was known as ‘The Blades’ after the knives produced in the area and Robson visits Peter Gribbon who has been grinding blades locally all his life. He tries his hand at grinding a blade, a hugely dangerous job. Losing fingers and legs, when grindstones burst, was a common occurrence in the 19th century. Peter explains the other health risks: “The dust off the grindstone used to get on the chest. In the old days they were dead at 30 and if they were on a dry stone even younger than that. But the wet grinders, 30, 35 they were old men and dead.” Also exposed to many dangers were the workers in the steel mills. Working hours were irregular and inside the mills was a combination of searing temperatures and toxic gases. Much of the steel produced was destined for the ship building industry and by 1900 Britain was building more ships then any other country in the world. The Royal family regularly visited the region to launch the metal giants. Ship launches had a sense of occasion with a brass band and families coming out to watch. Robson remembers his own experiences: “When they launched the ships and even when I was at the shipyard it really gave the area a sense of pride and belonging and identity. It was a very emotive time watching the launch of a ship, especially if you were part of the building process.” Robson’s first job was as an apprentice draughtsman at the Swan Hunter Yard and he takes a trip back with former colleague Bill Campbell. Robson says: “There was a lot of people working here in the early ‘80s when I arrived. And that’s where Will Crackett stayed. He was the office manager. He was the one who hauled us in when I announced that I wanted to be an actor when I was leaving in ’86. I did enjoy working here and there was a great sense of pride and worth when you see the ships go down.” Robson meets former shipbuilder Bob Growcutt who expresses his regrets about the industry. Bob says: “The working man, in my opinion, has never gotten the slightest little bit of recognition for his contribution to what he’s give this country. My biggest regret in my life really has to be somebody robbed me of passing my skills, knowledge and experience and my art back to the next generations that have been passed from my father to me, his father to him.” Robson also explores how the industrial revolution shaped the lives of the workers in the north and helped them to forge an identity. Jonathan Kinleysides, curator at the Beamish museam, explains to him: “It created very close-knit communities because underground you never knew when you needed the man next to you to save your life, so they depended on each other and the same on the surface. If one family fell on hard times everybody rallied ‘round and helped.” The only way workers had of protecting themselves and their families, was to band together in trade unions. Once unions began to gain strength around 1900, they became a force to be reckoned with. Strikes became more common and the first and only general strike in British history took place in 1926. Robson’s family have a connection with the most dramatic event of the strike, the derailment of the flying Scotsman. Robson explains: “My great-grandfather on my mother’s side, William Golightly, was President of the Northumberland Miners’ Association, and in a speech to striking miners he urged them to do everything they could to stop the transport of coal on the railways. So, fired up by these words, a group of striking miners sabotaged a railway line near Cramlington in the North East.” The miners mistakenly stopped a passenger train, rather then a freight train and despite not causing any fatalities or serious injuries, harsh sentences were handed down to them. Robson remembers: “One of those miners is called Arthur Wilson. And he used to cut my hair in a little shed behind our house. And when I used to get my haircut he never used to speak to me! I was going, ‘What’s wrong with him, he doesn’t like me?’ And one fella nudged me and he went, ‘He doesn’t like your middle name.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He went, ‘Golightly.’ He didn’t like William Golightly because they felt William could have supported them more in a campaign to get them released.” Ten years after the strike, Britain was in the grip of the great depression and unemployment sharply rose. In October 1936, 207 men set out on a march to the Houses of Parliament to draw attention to the extreme poverty being suffered by the people of the North East. The march sadly didn’t achieve what it set out to do but the Jarrow Crusade shows us that the people of Jarrow and the North East didn’t just lie down accept their fate; they fought for what they thought was right. Robson concludes: “If our story of how the North was built has an endpoint, then it must surely be the miners’ strike of 1984/1985. It was a watershed event and one that marked the end of the power of the miners’ union and also signalled a shift of an economy based on making things to one based on services. I saw first hand how the strike drove deep divisions into mining and villages but I also saw how people came together to help each other over the course of the year long strike.”