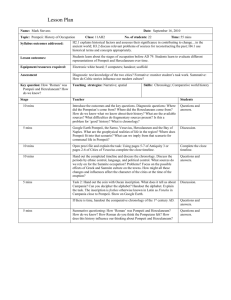

Ancient sources on Pompeii and Herculaneum

advertisement

Ancient sources on Pompeii and Herculaneum – packages of information 1. Primary and secondary sources: Primary sources date from the time of the events in question. They include monuments, inscriptions, human remains and accounts written by people who witnessed those events. Secondary sources date from after the events. They include accounts written by modern and ancient historians. There are few secondary sources on Pompeii and Herculaneum. 2. Ancient writers: Pliny the Younger (AD 61 – 113) is our main source on the eruption in AD 79. He and his uncle both witnessed it. Pliny the Elder died trying to rescue a friend. In about 112 AD Pliny the Younger wrote a letter to the historian Tacitus describing the eruption and recounting his uncle’s rescue attempt. Pliny the Elder (c. AD 23 – 79) was a naturalist who wrote about the geography and economy of Campania. Strabo (64/63 BC- c. AD 24) was a Greek geographer, who wrote about Campania. Cassius Dio (c. AD 155 – 235), also known as Dio Cassius, was a Roman historian who mentions the destruction of Pompeii in one of his volumes. Seneca (c. 4 BC – AD 65) was a Roman philosopher and naturalist who wrote about the earthquake that damaged Pompeii and Herculaneum in AD 62. Tacitus (c. AD 56 – after 117) was a Roman historian who mentions a fight between rival spectators at the gladiatorial games in Pompeii in AD 59. This caused the emperor Nero to ban all such games in the city for ten years. 3. Official Inscriptions: These were created by the Romans to record events, decrees, regulations, financial records, locations in cities, towns and the countryside, and magisterial positions. They were carved onto bronze plates, and fixed to the walls of public buildings – e.g. Nero’s decree banning gladiatorial games. 4. Wall notices: Public notices were painted on walls throughout the city. They included political posters, announcements about upcoming shows in the amphitheatre, plus upcoming property sales and rentals. 5. Graffiti: Graffiti was the main form of mass communications, so was everywhere. It was scratched into walls, as paint was expensive. The most common topics were gladiators and politics. Other topics included sex, love, drinking, gambling, plus advertising for bars, shops and brothels. Graffiti shows us that literacy levels were high in Pompeii and Herculaneum. 6. Wax tablets and rolls of papyri: Wooden tablets covered in wax have been recovered from Pompeii. These reveal the business activities of two merchants. They tell us detail about the legal status of freed slaves, family structures, land disputes and relations between neighbours. 1 1,800 rolls of carbonised papyri were recovered from Herculaneum. 7. Statues and sculptures: These were normally carved in marble or cast in bronze, and placed in temples, public squares and private homes. Subject matter included famous Romans, deities and family members. 8. Frescoes: Frescoes were wall paintings made on wet plaster. Most houses had them: elaborate scenes in rich ones, simple decorations in poor ones. 9. Mosaics: Mosaics are pictures and patterns made from thousands of chips of coloured glass, stone or pottery. They are found on floors, roofs and walls. In wealthy homes, they depict elaborate mythological scenes. In poor ones, they are simply black and white patterns. 10. Garden and household belongings: The gardens of rich houses were decorated with statues of deities. These same houses also contained ceramics, ornaments, vases, cutlery, jewellery, mirrors and other household items. Tables, chairs, beds and even a baby’s cradle have been found. 11. Human and animal remains: Very few skeletons survived intact in Pompeii. Most were destroyed during early excavations, due to carelessness on the part of the excavators. Many skeletal remains also decayed following the eruption, as they were not buried deeply enough to seal them from contact with oxygen. In the 1860s, Giuseppe Fiorelli put liquid plaster into the cavities he found, and produced moulds of bodies. They tell us a lot about how the people died. More recently, translucent epoxy resin has been used on new skeletal discoveries. Using MRI scanning, it is possible to tell the age, height, sex, appearance, health and even possible occupation of these victims of the eruption. Few human remains were initially found in Herculaneum, leading archaeologists to believe that most people fled the eruption. However, in 1982, many skeletons were discovered in boathouses at the edge of the ancient beach. These skeletons were better preserved than those in Pompeii, due to the depth at which they were buried. These bones have revealed that the victims came from a broad spectrum of society. 12. The limitations, reliability and evaluation of sources: Much of the evidence at Pompeii and Herculaneum has been stolen, lost or destroyed – by the elements, by careless archaeology, and by tourists. There is also not enough money available to properly preserve the site, so a third of Pompeii has been left untouched. There is also too little written evidence to back up the archaeological evidence. For these reasons, we cannot be certain that all our ideas about the cities are true. 2