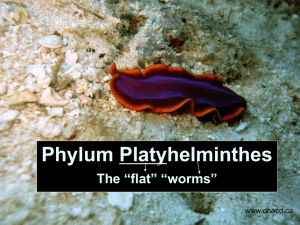

Phylum Platyhelminthes

advertisement

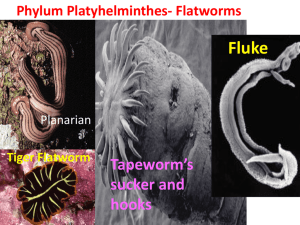

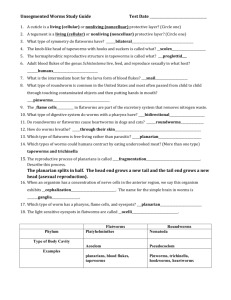

Phylum Platyhelminthes T H E F L AT W O R M S Body Plans Up until now, we have talked about animals with diploblastic body plans. What does it mean to be diploblastic? It means that you have two major cell layers: the endoderm (inside layer) and ectoderm (outside layer). What two animal Phyla have we studied that are diploblastic? Phylum Porifera (sponges) and Phylum Cnidaria (jellyfish, coral, and their relatives) However, from here on out, we will be exploring the triploblastic world. What does it mean to be triploblastic? It means that you have three major cell layers: the endoderm, the ectoderm, and the mesoderm (middle layer). What does YOUR mesoderm consist of? Body Plans Continued We will first start off with triploblasts that DO NOT have a coelem (body cavity). Remember that these animals are called Acoelemates. The prefix a- means NOT or NO, so “acoelemates” means no coelem (no body cavity). Why are flatworms special? What makes these guys different from Phylum Porifera and Phylum Cnidaria? Phylum Platyhelminthes have bilateral symmetry instead of asymmetry or radial symmetry. Phylum Platyhelminthes have a mesoderm which allows them to develop true muscles. Phylum Porifera and Phylum Cnidaria did not have a mesoderm and thus did not have true muscles. Phylum Platyhelminthes has a true nervous system, meaning a brain with attached nerve cords. Neither Phylum Porifera nor Phylum Cnidaria had a brain. Where do they live? Flatworms can live just about anywhere. There are terrestrial flatworms (meaning they live on the ground or underground). There are freshwater flatworms (meaning they live in streams and ponds). There are marine flatworms (meaning they live in the oceans). And there are parasitic flatworms. Where do you think parasitic flatworms live? If they are free living (meaning NOT a parasite), they fall into the class called Turbellaria. If they are parasitic, they fall into either the class called Trematoda (flukes) or the class called Cestoidea (tapeworms). Let’s start with Class Turbellaria. We’ll get to the other two classes in due time. Class: Turbellaria What and How do they eat? They can be either predators, scavengers, or herbivores. Believe it or not, a flatworm’s mouth is NOT near his head, but actually in the middle of his body on the ventral side. Inside the mouth opening is a tongue-like organ called the pharynx. The flatworm finds food, then secretes enzymes from the pharynx onto the food, which break it down into pieces small enough for the worm to eat. It would be the equivalent of you cutting your food into bite-size pieces that actually fit in your mouth. Exchanges with the Environment Even though flatworms have certain organs, they do NOT have lungs or a bladder. So how do they breathe and how do they get rid of wastes? DIFFUSION In the case of removing wastes, specialized cells called flame cells are responsible for the diffusion of wastes and maintaining homeostasis. Nervous System and Sense Organs Flatworms are the first animals to have a true nervous system, meaning that they have a brain and have 3 distinct types of nerve chords. Sensory nerves respond to an external stimulus and send a signal to the brain. Motor nerves receive a signal from the brain and route it to its destination in the body. Association nerves serve as connections between sensory and motor nerves. Sense Organs Flatworms have two eyespots on the top of their head that detect light. Most flatworms will move AWAY from light. They also have auricles on the side of their head. The auricles look like what we would call ears, but actually function more like two tiny noses, and are used to search out food. Turbellarian Reproduction Like the sponges we studied before, turbellarians are monoecious. What does it mean to be monoecious? Turbellarians can be reproduce sexually or asexually if a partner is not available. Asexual reproduction occurs through a process called transverse fission. This is where the worm can separate itself into two halves and each half will become a new worm. Class Trematoda: Flukes Most flukes are flat and oval. They feed on host cells. Almost all adult flukes are parasites of vertebrates, while immature flukes can be parasites of vertebrates or invertebrates. Have at least two different forms: an adult and one or more larval stages. Life Cycle of a Trematode 1. An egg hatches in freshwater and a ciliated larval form called a miracidium swims out. 2. The miracidium swims until it finds a good intermediate host, usually a snail. Once inside the snail, it develops into its next larval form, a sporocyst. This is where asexual reproduction occurs. 3. The asexual stage results in the next larval form, the cercaria. A cercaria has a digestive tract, suckers, and a tail. Cercaria leave the snail and swim freely until they find the second host. This host could be an invertebrate, a vertebrate, or even a plant. 4. The final host eats the invertebrate, vertebrate, or plant infested with the cercaria. Once inside the final host, usually a vertebrate, the cercaria develops into a juvenile. 5. The juveniles mature into adults inside the final host. As adults, they are able to engage in sexual reproduction and produce lots of fertilized eggs. The eggs then get pooped out by the host and end up in the water supply ready to begin the cycle again. Life Cycle of a Typical Fluke Class Cestoidea Characteristics: Tapeworms Tapeworms almost always parasitize the digestive tract. Can be anywhere from 1mm to 25m in length. There have been rare cases where tapeworms have been even longer than 25m. Tapeworms lack a digestive system of their own. Why might this be? Adult tapeworms consist of a long series of repeating units called proglottids. Each proglottid contains its own complete set of reproductive structures. Instead of a true mouth, tapeworms have a sucker-like organ called a scolex, which it uses to attach itself to the digestive tract of its host. Cestoidea Reproduction Tapeworms are monoecious. What does this mean again? In tapeworms however, if no appropriate mate is present, they CAN self-fertilize! Where would we find a tapeworm? In any vertebrate animal, but most commonly in Beef Pork Fish Lamb Dogs From all these sources, tapeworms find their way into US!!!! Tapeworm Life Cycle How Do I Know If I Have a Tapeworm or other Infectious Worm? If you live in North America or Eastern Europe, you probably don’t have an infectious or parasitic worm. Why not? We wear shoes when we go outside. Our meat supply is raised under stringent standards and inspected before it reaches our table, AND we COOK our meat, which kills any unnoticed eggs. Our pets are usually not raised on a farm with access to infected vegetation, AND are usually medicated and/or vaccinated for worms. (One exception-- newborn animals.) During winter months, parasitic and infectious worms cannot survive here outside of a host, it’s just too cold. But…What If???? On the off chance that you do become infected, 9 times out of ten, you won’t know! Most people infected with a tapeworm show no signs or symptoms until the tapeworm reaches sufficient size to cause an intestinal blockage. In this case, it needs to be removed surgically. Sometimes, people experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anemia due to B12 deficiency, and weight loss. And if it’s a fluke, you will experience the same types of symptoms. In even rarer cases, pieces of a tapeworm can break off and infect other areas of your body, such as your liver, heart, and even your brain. But again, this is EXTREMELY rare! Removal