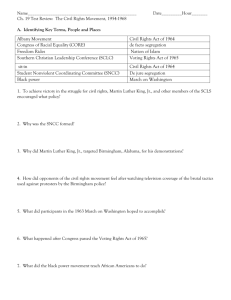

The Civil Rights Movement

advertisement

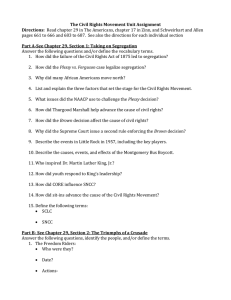

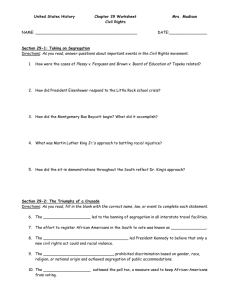

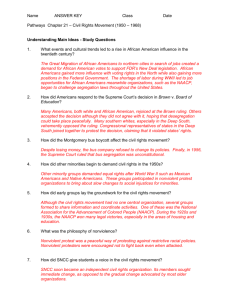

The Civil Rights Era Postwar Movement towards Racial Integration African Americans fought in World War II and also worked in war industries in the United States during the war. After the war, they once again faced the racial discrimination that had been traditional before the war, but many people took bold actions to end discrimination and promote integration. Integration of the U.S. Armed Forces When Congress refused to adopt anti-lynching laws and a ban on poll taxes, in 1948, President Harry Truman issued an executive order to integrate the U.S. armed forces and to end discrimination in the hiring of U.S. government employees. In turn, this led to civil rights laws enacted in the 1960s. Jackie Robinson In 1947, Jackie Robinson was the first African American to play for a major league baseball team in the U.S., the Brooklyn Dodgers. This led to the complete integration of baseball and other professional sports. Robinson was the National League’s most valuable player in 1949 and the first African American in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Until this time, African Americans played professional baseball in the Negro League. In the Brown v. Board of Education case (1954), the U.S. Supreme Court declared that state laws establishing “separate but equal” public schools denied African American students the equal education promised in the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court’s decision reversed prior rulings dating back to Plessy V. Ferguson in 1896. Many people were unhappy with this decision, and some even refused to follow it. The governor of Arkansas ordered the National Guard to keep nine African American students from attending Little Rock’s Central High School; President Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock to force the high school to integrate. Brown v Board of Education Reaction to the Brown Decision Official reaction to the ruling was mixed. In Kansas and Oklahoma, they expected segregation to end with little trouble, in Texas, they promised compliance but said it could “take years”, and in Mississippi and Georgia they vowed total resistance. To hasten compliance, the Supreme Court handed down a second decision ordering schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” The Montgomery Bus Boycott On December 1, 1954, Rosa Parks, a seamstress and NAACP officer, in Montgomery, Alabama, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus so that a white man could sit down. The Montgomery Improvement Association, led by a young Martin Luther King, organized a boycott of the buses. For 381 days, African Americans refused to ride the buses until the Supreme Court finally outlawed bus segregation. Martin Luther King and the SCLC Martin Luther King based his ideas of nonviolent resistance on those of Gandhi. King joined with more than 200 ministers and civil rights leaders to found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which staged protests and demonstrations throughout the South. Letter from a Birmingham Jail Letter written on April 16, 1963, by Martin Luther King from the Birmingham City Jail in response to a statement made by eight white Alabama clergymen in which they criticized MLK, as an “outside agitator” King argued that without nonviolent forceful direct actions, true civil rights could never be achieved and that "one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws." The letter includes the famous statement "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere" Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee In April of 1960, students at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee - SNCC. Many college students viewed the pace of change as too slow. SNCC, hoping to harness their energy, would create one of the most important student activist movements in American history. SNCC vs. SCLC Two civil rights groups prominent in the struggle for African American rights in the Sixties were the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Although the SCLC and SNCC started as similar organizations, they grew to differ over time., especially in the SNCC’s changing composition. SCLC SNCC Founding Founded by Martin Luther King, Founded by African American Jr. and other ministers and civil college students with $800 rights leaders received from the SCLC Goal To carry on nonviolent crusades To speed up changes mandated against the evils of second class by Brown v. Board of Education citizenship Original Tactics Marches, protests, and demonstrations throughout the South, using churches as bases Sit-ins at segregated lunch counters all across the South; registering African Americans to vote, in hopes they could influence Congress to pass a voting rights act Later tactics Registering African Americans to vote, in hopes they could influence Congress to pass a voting rights act Freedom rides on interstate buses to determine if southern states would enforce laws requiring segregation in public transportation Original Membership African American and white adults African American and white college students Later Membership Same as original African Americans only; no whites Original Philosophy Nonviolence Nonviolence Later Philosophy Same as original philosophy Militancy and violence, “black power” and African American pride Television Changes The first regular television broadcasts began in 1949, providing just two hours a week of news and entertainment to a very small area of the East Coast. By 1956, over 500 stations were broadcasting all over America; bringing news and entertainment into the living rooms of most Americans. Kennedy/Nixon Presidential Debates In the 1960 national election campaign, the Kennedy/Nixon presidential debates were the first ones ever shown on TV. Seventy million people tuned in. Although Nixon was more knowledgeable about foreign policy and other topics, Kennedy looked and spoke more forcefully because he had been coached by television producers. Kennedy’s performance in the debate helped him win the presidency. The Kennedy/Nixon debates changed the shape of American politics. Sit-ins In February 1960, students from North Carolina’s Agricultural and Technical staged a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter at a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina. Television brought coverage of the protests and the ugly face of racism – whites beating, jeering at, and pouring food over students who refused to strike back - into homes throughout the United States. By late 1960, students had descended on and desegregated Jim Crow lunch counters in 48 cities in 11 states. Freedom Riders In 1961, six whites and seven blacks set out on a special bus ride throughout the South to test Supreme Court decisions banning segregation on interstate bus routes and segregated facilities in bus terminal. These Freedom Riders were beaten and severely injured. In Anniston, Alabama, a mob of 200 whites tossed a fire bomb destroying the bus. SNCC members volunteered to continue the ride. After the volunteers were beaten by police in Birmingham, Alabama, Attorney-General Robert Kennedy sent 400 federal marshals to protect the riders. Marching to Washington To persuade Congress to pass President Kennedy's proposed civil rights bill, on August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 people converged on Washington, D.C. Martin Luther King appealed for peace and racial harmony in his “I have a dream” speech. Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Two weeks after King’s historic speech, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was firebombed, claiming the lives of four young girls. TV News Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement - 1 TV newscasts also changed the shape of American culture. Americans who might never have attended a civil rights demonstration saw and heard them on their TVs in the 1960s. In 1963, TV reports showed helmeted police officers from Birmingham, Alabama using high pressure water hoses to spray African American children who had been walking in a protest march. TV News Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement - 2 The reports also showed the officers setting police dogs to attack them, and then clubbing them. TV news coverage of the civil rights movement helped many Americans turn their sympathies towards ending racial segregation and persuaded Kennedy that new laws were the only way to end the racial violence and to give African Americans the civil rights they were demanding. Civil Rights Act of 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This law prohibited discrimination based on race, religion, national origin, and gender. It allowed all citizens the right to enter any park, restroom, library, theater, and public building in the United States. One factor that prompted this law was the long struggle for civil rights undertaken by America’s African American population. Civil Rights Act of 1964 Another factor was King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech; its moving words helped create widespread support for this law. Other factors included previous presidential actions that combatted civil rights violations, such as Truman’s in 1948 and Eisenhower’s in 1954, and Kennedy’s sending federal troops to Mississippi (1962) and Alabama (1963) to force integration of public universities there. Freedom Summer In 1964, in what was known as Freedom Summer, SNCC concentrated its efforts on registering voters in Mississippi, where 90% of African Americans were unable to vote. Some 1,000 volunteers, mostly white, one-third female, went to Mississippi to help the mostly African American SNCC, staff register black voters. The project encountered violent opposition, including the abduction, torture, and murder of three volunteers, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney by the Ku Klux Klan. Voting Rights Act of 1965 In 1965, the SCLC decided to conduct a major voter registration campaign in Selma, Alabama, where African Americans were more than half the population but only 3% of the registered voters. The SCLC hoped to provoke a hostile white response that would force the Johnson administration to sponsor a federal voting-rights law. Television news broadcast images from Selma of police on horseback attacking demonstrators, using tear gas, whips, and clubs. Ten weeks later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. SNCC Evolves In the later 1960s, led by fiery leaders such as Stokely Carmichael, SNCC focused on "black power” and then protesting against the Vietnam War. As early as 1965, James Forman said he didn’t know “how much longer we can stay nonviolent” and in 1969, SNCC officially changed its name to the Student National Coordinating Committee to reflect the broadening of its strategies. Malcolm X New leaders, including Malcolm X, were emerging who argued that blacks should take control of their communities, livelihoods, and culture. Malcolm X’s message that blacks should separate from white society appealed to many African Americans and their growing pride in their identity. His call for armed self-defense frightened most whites and many moderate African Americans. After a pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm X still burned with a hatred of racism and injustice but his views towards whites changed. On Feb. 21, 1965, he was shot and killed. Black Panthers The Black Panther Party achieved national and international notoriety through its involvement in the Black Power movement from 1966 until 1982, becoming an icon of the counterculture of the 1960s. They instituted programs designed to alleviate poverty, improve health among inner city black communities, and soften the Party's public image. However, the group's political goals were often overshadowed by their confrontational, militant, and violent tactics against police. Individual Rights During most of the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren Court, as it was known, became famous for issuing landmark decisions, such as declaring that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, that the Constitution includes the right to privacy, that the right of free speech protects students who wear armbands as an antiwar protest on school grounds, and that all states must obey all decisions of the Supreme Court. Miranda v. Arizona In 1963, the Warren Court issued another of its landmark decisions, Miranda v. Arizona. Police must inform suspects of their constitutional rights at the time of arrest. The case involved a man named Ernesto Miranda, who was convicted and imprisoned after signing a confession, although, at the time of his arrest, the police questioned him without telling him he had the right to an attorney and the right to remain silent. The Miranda decision strengthened Americans’ individual rights. Engel v. Vitale Engel v. Vitale (1962) • Court ruled that it is unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and encourage its recitation in public schools • held that the mere promotion of a religion is sufficient to establish a violation, even if that promotion is not coercive Gideon v. Wainwright Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) • unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own attorneys New York Times v. Sullivan New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) • extended the protection offered the press by the First Amendment • held that debate on public issues would be inhibited if public officials could sue for inaccuracies that were made by mistake • made it more difficult for public officials to bring libel charges against the press, since the official had to prove that a harmful untruth was told maliciously and with reckless disregard for truth The assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, in November, 1963, was a tragic event with a twofold political impact. 1. The assassination showed Americans just how strong their government was because, although the president could be killed, the U.S. government would live on. 2. The assassination gave the new president, Lyndon Johnson, the political capital to force his domestic legislative agenda through Congress. This included the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which launched Johnson’s “War on Poverty” and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in American schools and other public places. Tragedy in Dallas The Other America: Poverty in the U.S. Michael Harrington wrote The Other America (1961) • argued that up to 25% of the nation was living in poverty • many believe that this book is responsible for President Lyndon B. Johnson's "War on Poverty" The Great Society During a 1964 speech, President Johnson summed up his vision for America in the phrase “the Great Society.” His programs to make the United States a great society would secure civil rights for all Americans and eliminate poverty. The Medicare program is an important legacy of the Great Society, as are policies and programs that sought to improve elementary and secondary education, to protect the environment, and to reform immigration policies. Voting Rights Act of 1965