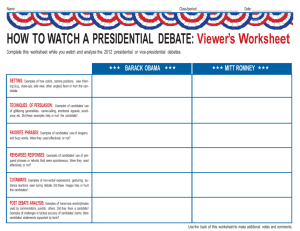

Windows into Teaching and Learning in Social Studies

advertisement