Standard 4, Artifact 2, 1884 Presidential Election

advertisement

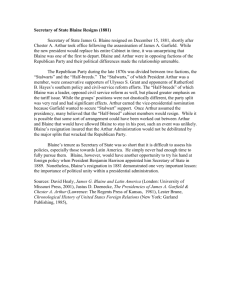

David K. Thomas 12-13-13 HI336 Final Paper Professor Leonard Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion: A Historical Fallacy? “I have not a particle of ambition to be president of the United States….[but should I] be selected as the nominee, my sense of duty to the people and my party would dictate my submission to the will of the convention.”1 So wrote Grover Cleveland on June 30, 1884, in a personal letter to Daniel Manning, who would later become the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under Cleveland. However, Cleveland not only won the 1884 presidential election, but he was the first Democrat to be elected to the oval office since James Buchanan who was president from 1857 to 1861. A brief look at Cleveland’s past does little to explain how a largely unknown governor of New York state could receive the Democratic presidential nomination and then win an election over the Republican candidate James G. Blaine. Blaine had served as a member of the House Representatives, the U.S. Senate, was the Speaker of the House and then later U.S. Secretary of State. Blaine was above all a man of magnetism; everyone who met Blaine simply loved or hated him with no emotions in between. As Richard E. Welch Jr., a biographer of Cleveland accurately notes, “One can always view election results from two different perspectives: why the loser lost and why the winner won.”2 Perhaps then, it would be better to ask why did Blaine lose the 1884 presidential election? Many historians would argue that Cleveland was elected largely because a New York clergyman associated with Blaine alienated voters by making an anti-Catholic remark during the last week of the campaign. This remark then caused the popular vote to shift just enough to change the results of the state of New York, thus altering the Electoral College and declaring 1 Grover Cleveland, Letters of Grover Cleveland 1850-1908. Ed. Allan Nevins (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Riverside Press, 1933), p. 35. 2 Richard E. Welch, The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas, 1988), p. 41. 1 Cleveland to be victorious. While an interesting notion, this historical theory does nothing to explain the complexities of the 1884 presidential election or the larger historical implications. On October 30, 1884, during the final week of the presidential campaign, Blaine attended a clerical meeting in which various local religious leaders in New York gave speeches showing their support for Blaine. At one point, Rev. Samuel D. Burchard promised to support Blaine for the presidency of the U.S. and stated to the gathered crowd that “We are Republicans and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism, and rebellion. We are loyal to our flag. We are loyal to you.”3 The popular historical argument goes that this remark from Burchard offended many Irish voters during the 1884 election and caused them to vote for Cleveland instead. The New York Times, a rather proCleveland newspaper at the time, stated that “No utterance of any politician during the campaign now ending has so aroused the community, and especially Roman Catholics.”4 Blaine himself did not take note of what Burchard had said at the time, as he was very tired. He also failed to disassociate himself from Burchard later, however, even though Blaine’s own mother was an Irish Catholic. To make matters worse, some newspapers falsely subscribed the words of Burchard to Blaine himself. In the end, Cleveland won the 36 electoral votes of New York state by a little over 1,000 popular votes in over 1.1 million votes cast.5 Mark Wahlgren Summers’ book, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion: The Making of a President is perhaps the most extensive study of the U.S. presidential election of 1884 and, as the title implies, highlights the importance of this single event during the election. Many other historians have done so as well. 3 Mark W. Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion: The Making of a President, 1884 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2000), p. 282. 4 “Rum, Romanism, Rebellion: The Rev. Dr. M’Glynn’s Counsel to Catholics,” The New York Times, November 2, 1884, p. 7. (unless otherwise noted, newspaper articles did not name the author) 5 Election of 1884, The American Presidency Project, (online resource) http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ showelection.php?year=1884. 2 Unfortunately, the popular historical argument concerning Burchard’s “rum, romanism, and rebellion” remark does not add up. There are several issues with this historical argument without even considering outside political forces. As Allan Nevins astutely notes, “If the phrase was new, the idea was old.” In fact, in 1876 James A. Garfield stated that the Republicans had been “worsted by the ‘combined power of rebellion, Catholicism, and whiskey’” when he incorrectly thought that a Democrat was going to claim the Oval Office.6 Burchard did not even originate the alliteration of his statement. A Maine newspaper published in 1880 stated that the spirit that ran the Democratic Party was “The Spirit of Rule or Ruin (as in 1861), Rum and Romanism, Rebellion, and Despotism!”7 Therefore, conceptually this statement from Burchard was not at all original, nor was the alliteration. Attributing Blaine’s failure to win the Irish vote to Burchard’s remark also fails to look at the event in historical context. Charles Edward Russell, in his biography of Blaine titled Blaine of Maine, argues that “The Irish vote was becoming Republican.”8 Russell is correct in this assertion because “Blaine polled a bigger Irish vote in New York City, Chicago, and Boston than any Republican presidential candidate before him.”9 However, the issue for the Republicans in this instance was that they had to win the Irish Catholic voters to their side; the Democrats simply had to bring them back in. Likewise, Russell argues that “The Irish voters that had turned in such numbers to Blaine were mostly of the Catholic faith. They took Burchard’s sentence as an intolerable and wanton insult to their religion, and returned to the Democratic” party.10 6 Allan Nevins, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1932), p. 182. Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion, p. 80. 8 Charles Edward Russell, Blaine of Maine; His Life and Times (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1931), p. 400. 9 Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion, p. 292. 10 Russell, Blaine of Maine, p. 401. 7 3 There are many dissenting historical voices which claim that Cleveland was elected for reasons other than Burchard’s anti-Catholicism. It is notable that nearly all of these varying theories agree that Cleveland was victorious largely because of the political mishaps of Blaine. For instance, one biographer, Irving Stone, writes bluntly that “It was James Mulligan who defeated James Blaine for the presidency.”11 This is a reference to James Mulligan, a Boston bookkeeper who discovered numerous letters that confirmed that Blaine had sold his influence while in the House of Representatives to railroad interests, the most extensive and notable being Jay Gould. These letters cost Blaine the Republican nomination in 1876 and again in 1880. Relating to the Mulligan letters, Don C. Seitz argues in The “Also Rans” that a particular cartoon depicting Blaine as a tattooed man with the writing from the Mulligan Letters imprinted on his body was particularly damning to Blaine. The cartoon was possibly “the most far-reaching, effective cartoon ever drawn and being widely circulated did dreadful damage to the Republican candidate.”12 The cartoon was drawn by Bernhard Gilliam, a cartoonist for Puck magazine, which was known for its political satire in general and for its sympathy for Cleveland’s campaign. Interestingly, even Blaine himself did not blame his defeat on Burchard’s remark. Instead, in an interview originally printed in the Boston Journal, Blaine attributed his loss to the “Independent Republicans” (the Mugwumps) for bolting from the Republican Party and the “Republican Prohibitionists” who had decided to vote for a third-party candidate, John St. John, instead. When the remark of Burchard was mentioned by the interviewer, Blaine stated that despite Burchard’s gaff, he still “had thousands and thousands” of New York Irish votes 11 Irving Stone, They Also Ran: The Story of the Men Who Were Defeated for the Presidency (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1943), p. 241. 12 Don C. Seitz, The "Also Rans"; Great Men Who Missed Making the Presidential Goal (Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1968), p. 294. 4 anyway.13 Blaine appears to be at least partially justified in holding dissenting Republicans responsible for his loss because early in the campaign “influential Republican newspapers…lifelong members of the party, declared….that they could not and would not support the [Republican] ticket, if Governor Cleveland” received the Democratic nomination.14 The fact that so many Republicans would be willing to bolt from the party upon the nomination of Blaine to run for the Republicans stands as a testament to his polarizing personality. Although Blaine may be remembered for various scandals and for losing the 1884 United States presidential election, he still had many and often powerful supporters. Thomas W. Knox shows his support for Blaine in an 1884 biography on Blaine and his running mate John A. Logan. The “biography” which was little more than a pro-Blaine propaganda piece that came out just in time for the election. Knox argues that Blaine “bears the love of all, and his charity and benevolence to the poor and needy are almost without bounds.”15 Knox even dedicated this book “to the Republican Party, which has controlled the destinies of a great nation….and safely guided it in the greatest era of progress the world has ever known.”16 Moreover, various capitalists such as Jay Gould certainly remembered Blaine from the years when he sold his influence in the House of Representatives for the benefit of railroad tycoons. When studying the 1884 presidential election one must keep in mind that there were numerous last minute mistakes other than Burchard’s gaff that could have cost Blaine the election. One of Cleveland’s most praising biographers was Allan Nevins and even he focuses more on the mistakes of Blaine than he does on the political gifts of Cleveland when writing about the 1884 presidential election. In particular, Nevins cites a “Prosperity dinner” that was 13 “Announcements,” The Waterville Mail, November 21, 1884, p. 1, (Microfilm). Edward Stanwood, James G. Blaine: American Statesman (New York: AMS Press, 1908), p. 279-280. 15 Thomas W. Knox, The Lives of James G. Blaine and John A. Logan (Hartford, Connecticut: The Hartford Publishing Company, 1884), p. 223. 16 Ibid., p. III. 14 5 meant to raise badly needed funds for Blaine in the final week of the campaign. It took place just hours after Rev. Burchard made his intolerant remark towards Irish Catholics. Present at this dinner held in Delmonico’s, a famous New York restaurant, were numerous wealthy capitalists from the time period. Unfortunately for Blaine, the dinner failed to raise substantial funds and instead alienated him from many working-class citizens. Nevins argues that “At a stroke [Blaine] lost the votes of thousands of workingmen.”17 Articles from The New York Times certainly support this claim. The critically-titled article “Feeding Their Candidate: The Monopolists’ Dinner to the Tattooed Man” referenced both this dinner and the “Mulligan Letters” and portrayed Blaine as a politician completely out of touch with working-class citizens.18 Another article from The New York Times went so far as to accuse Blaine of mortgaging “his Administration within a week of the election to the most notorious gang of jobbers that the country contains.”19 Blaine appeared to be both corrupt and disconnected with the common American people. Notably, even if it is true that Cleveland was legitimately uninterested in becoming president as late in the political season as June, 1884, Blaine was facing a different psychological issue when running for the Oval Office. Because of reoccurring troubles with scandals such as the Mulligan Letters, “Blaine himself had serious misgivings as to his own ability to be elected if nominated” in 1884.20 This mindset was partially caused by the fact that he had failed to secure the Republican nomination in both 1876 and 1880. Richard Welch also notes that during the 1884 presidential election that there was a short-term economic recession that could have harmed Blaine because the Republicans were in control of the Oval Office and would therefore receive 17 Nevins, Grover Cleveland, p. 183. “Feeding Their Candidate: The Monopolists’ Dinner to the Tattooed Man,” The New York Times, October 30, 1884, p. 2. 19 “Some of Blaine’s Hosts,” The New York Times, October 30, 1884, p. 3. 20 Stanwood, James G. Blaine, p. 273. 18 6 more blame for economic issues. 21 Blaine himself was aware of this, which likely furthered his anxiety. Various third party candidates were also working against Blaine. General Benjamin F. Butler was the most prominent of the third party candidates and as governor of Massachusetts, he had a particularly strong following in that state. In his biography on Butler, Howard P. Nash, Jr. argues that Butler “took an active part in the campaign only in the hope of effecting Cleveland’s defeat” because he believed Cleveland was an enemy to free labor.22 Ironically, Blaine felt that Butler’s campaign was more damaging to his own chances of being elected than Cleveland’s and predicted that Butler would receive roughly 250,000 votes overall. Blaine simply wanted Butler to stay out of the election entirely if he truly wanted to hurt Cleveland instead of taking potential votes away from the Republicans.23 There was also the candidacy of the aforementioned John St. John, a prohibitionist, that took votes away from the Republican Party. When all was said and done, in the state of New York, “563,154 [votes were cast] for Cleveland, 562,005 for Blaine, 25,016 for St. John, and 16,994 for Butler.”24 Nationally, Cleveland’s total popular vote was only 0.7% higher than Blaine’s even though he had 219 electoral votes to Blaine’s 182. Also on a national scale, Butler received the most votes of the Third Party candidates with roughly “175,000 votes, running best in Michigan, fairly well in Massachusetts, and very badly in New York.”25 The other key third party candidate was Belva Ann Lockwood, a champion of women’s rights, who was demanding suffrage for all American women. Although she herself could not vote, she argued that she could still be voted for. Little came of her candidacy and of her possibly 21 Welch, The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland, p. 41. Howard P. Nash, Stormy Petrel: The Life and Times of General Benjamin F. Butler, 1818-1893 (Rutherford, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1969), p. 296. 23 Stanwood, James G. Blaine, p. 285. 24 Nash, Stormy Petrel, p. 297. 25 Nevins, Grover Cleveland, p. 187. 22 7 “working behind the scenes with Congressional Republicans, hop[ing] to derail Cleveland’s victory.”26 However, as Lockwood’s biographer, Jill Norgren, astutely notes, the states of Indiana and New York were absolutely essential in the 1880 presidential election for a Republican victory, and by extension, the 1884 presidential election as well. Likewise, when speaking of Democrats less than two weeks before the election would be held, Blaine stated that “Instead of memories of the Union [Democrats] invoke the prejudices of the rebellion in their aid and ask that New York and Indiana shall join in the unholy alliance and turn the National government over to the South.”27 Actually Blaine and Logan would lose Indiana, partially because of the fact that Cleveland’s running mate, Thomas A. Hendricks, was from that state and at various times had served in the House of Representatives, the Senate and as the governor of Indiana.28 The various characters running in the 1884 presidential election certainly gave it entertainment value, or troubling potential outcomes depending on one’s perspective. Summers states in the opening words of his introduction to Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion that the “The presidential election of 1884 was one of the gaudiest in history, the campaign itself nearly legendary.”29 This is because of the clash of personalities between the magnetic, if not polarizing, character of Blaine and the almost dark horse candidacy of Cleveland. Unfortunately, this is all that the 1884 election has come to be known for, when in fact there were legitimate and important political and social issues during this time period. Some of the most recognizable moments of the 1884 presidential election come from the slogans “Blaine! Blaine! James G. Blaine! Continental liar from the state of Maine! Burn this letter!” and “Ma! Ma! Where’s my 26 Jill Norgren, Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would Be President (New York: New York University Press, 2007), p. 141. 27 “Announcements,” The Waterville Mail, October 24, 1884, p. 1, (Microfilm). 28 Election of 1884, The American Presidency Project (online resource). 29 Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion, p. XI. 8 pa? Gone to the Whitehouse? Ha, ha ha!” Furthermore, there is no denying that in The Republican Campaign Text-Book from 1884, Democrats are accused of every atrocity from large-scale financial irresponsibility to hating and discriminating against Union Soldiers.30 Arguably, the event that the presidential election of 1884 is best known for is Cleveland’s affair with a young woman named Maria Halpin, a scandal that could very well have derailed Cleveland’s entire political career. However, Cleveland won support from some of the most unlikely of individuals because of his purported honesty and his willingness to openly share information with the press concerning his affair with Halpin. One such person was Maria Halpin’s former preacher who stated that even though he did not intend to vote for Cleveland, “I think him an honest man.”31 It also helped Cleveland that newspapers such as The New York Times appeared to be particularly pro-Cleveland, most likely because they liked the notion of having a politician from their home state in the White House. This does not mean that Cleveland was without his critics. One newspaper, The Independent, stated that if the allegations against Cleveland having an affair were true, then “this is a most conclusive reason why the American people should not now make him President of these United States.”32 Their reasoning was that if Cleveland could be indecent in his private life, then his political life could be little better and would be a detriment to the entire nation. Despite such damning opinions, Cleveland managed to make the Halpin scandal rather irrelevant during the election. The Republicans also failed to capitalize on this matter and instead focused more on the political issues between the major political parties. 30 The Republican Campaign Text Book for 1884 (New York: Republican National Committee, 1884). “Maria Halpin: A Buffalo Clergyman Speaks His Mind, Mrs. Halpin’s Former Pastor Says that Grover Cleveland Acted Nobly,” The Boston Globe, October 31, 1884, p. 5. 32 “Grover Cleveland,” The Independent, September 4, 1884, p. 16. 31 9 Some of the political and social issues that the Republicans and Democrats focused on included the Chinese Exclusion Act and, by extension, the rights of free (white) labor. Despite the rather common opinion that the Republicans were the party of higher morals during this time period, it was actually the Republicans, with the leadership of Blaine in particular, who pushed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act through Congress. Amongst various racist statements, Blaine bluntly asserted, “I am opposed to the Chinese coming here; I am opposed to making them citizens; I am opposed to making them voters.”33 The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first act in U.S. history to actively discriminate against a certain ethnic group by denying them the right to immigrate to the United States. Interestingly enough, although a major social issue, the Republicans and Democrats did little to distinguish themselves on this blatantly racist law. The Republican Party Platform of 1884 states that “we pledge ourselves to sustain the present law restricting Chinese immigration, and to provide such further legislation as is necessary to carry out its purposes.”34 Limiting Chinese immigration was all part of the larger goal of politicians to appeal to working-class laborers. Likewise, in the Republican 1884 platform, it reads “We favor the establishment of a national bureau [and] the enforcement of the eight hour law.”35 On the other hand, the Democrats stated in their 1884 Party Platform that “we nevertheless do not sanction the importation of foreign labor” in any situation as it would harm free white labor.36 On other political and social issues, the Republicans and Democrats found themselves very much at odds. Feelings of political sectionalism with roots in the U.S. Civil War are easily observable and are perhaps what distinguished the two parties the most. The Republicans 33 Andrew Gyory, Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), p. 4. 34 Republican Party Platform of 1884, The American Presidency Project, (online resource) http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29626. 35 Ibid. 36 Democratic Party Platform of 1884, The American Presidency Project, (online resource). http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29583#axzz2jiMDSc2G 10 credited themselves with “saving the union” in their 1884 Party Platform and went on to say that “in Southern States….the will of a voter is defeated.”37 Moreover, when speaking of Blaine’s running mate John A. Logan of Illinois, Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont remarked that “We have never had a stronger candidate for the Vice-Presidency…He served in two wars, and carries three wounds. The soldiers will rally to him in force.”38 Knox also mentions that Edmunds predicted that Logan would be able to win the state of Indiana for Blaine, but this was not to be. Notably, Knox neglects to mention that Edmunds thought that Blaine himself was “a political menace.”39 The Democrats also had fresh memories of the Civil War as well. In their 1884 Party Platform they emphasized “the reserved rights of the states; and the supremacy of the Federal Government within the limits of the Constitution.”40 With so many political mishaps and important issues on the table, it becomes increasingly difficult to believe that one single, unoriginal statement, whose significance is rather questionable, changed the course of the 1884 presidential election, and by extension, the history of the United States. David F. Healy wisely notes that “A shift in New York State of 600 votes would have elected Blaine.” With that in mind Healy states “When elections are that close, any arbitrarily selected factor…..might be said to be the determining one….In the end, Blaine failed to win the election because he was unlucky.”41 Even though Summers in his book ultimately subscribes to the “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion” theory he does add that “Just about anything could have defeated Blaine in New York, with so small a margin.”42 I see little reason to think 37 Republican Party Platform of 1884, The American Presidency Project (online resource). Knox, The Lives of James G. Blaine and John A. Logan, p. 349. 39 Nevins, Grover Cleveland, p. 178. 40 Democratic Party Platform of 1884, The American Presidency Project, (online resource) [Emphasis mine]. 41 David F. Healy, Statesmen Who Were Never President (Ed. Kenneth W. Thompson, Lanham, Maryland: University of America, 1996), p. 40. 42 Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion, p. 292. 38 11 that it was the unfortunate remark made by Burchard that defeated Blaine as opposed any of the other factors that have been noted above. Although Healy makes an excellent point in his assertion that Blaine could have lost New York for any number of reasons, he does not comment on why exactly New York was the tipping point that decided the election. The fact is, even by winning the states of New York and Indiana, as crucial as they had been for a Republican presidential victory in 1880, Cleveland could never have been elected without the solidly Democratic South. Cleveland received over 60% of the popular vote in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia, nearly 70% of the popular vote in Texas and 75.3% of the popular vote in South Carolina. Cleveland needed 201 electoral votes or more in order to become president and the southern states that had seceded during the American Civil War provided him with 107 electoral votes in 1884 out of the total 401 electoral votes of the Electoral College. The four “border states” during the American Civil War gave Cleveland an additional 40 electoral votes.43 The legacy of the “Solid South” began with the 1880 presidential election and it would not be until 1920 that even a single one of the eleven states (Tennessee) that had seceded during the Civil War would vote for a Republican for president.44 One can infer that the solidifying of the Democratic South is directly related to the end of the Reconstruction Era, which concluded in 1877 when Northern troops ceased to occupy the South. This also marks the point when Republicans ceased to have any tangible political sway in local and state politics in the South. This is partially because the voting rights of African Americans, who would remain loyal to Republicans for years to come, were brutally suppressed during this time. However, sometimes the votes of African Americans were still counted in disturbing ways. There was a gruesome saying in the South that went “A dead darkey always 43 Election of 1884, The American Presidency Project, (online resource). Election of 1920, The American Presidency Project, (online resource). http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1920 44 12 makes a good Democrat and never ceases to vote” and this occurred on a large scale in Louisiana. Other southern states allowed their dead white citizens to count as Democratic votes as well.45 Such dishonesty and foul-play is what would keep the South a stronghold for the Democrats for decades to come. Even with the Solid South, Democrats found that they were unable to elect a Democrat other than Grover Cleveland until 1912 when Woodrow Wilson was elected. Even then, Wilson’s victory was largely because the Republican vote was split between the Republican candidate, William H. Taft and the Progressive candidate, Theodore Roosevelt. When one researches an overview of the Electoral College during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it becomes clear that it was only in rare instances that Democrats could convince a well-populated, northern state, such as New York in 1884, to break ranks and join what Blaine considered to be the “unholy alliance” of the South.46 The Democrats had a virtual stranglehold on the South, and to a lesser degree, the Border States. There were elections in which the Democrats were victorious in acquiring the electoral votes of western and mid-western states during this time period. However, these states had lower populations and few electoral votes as a result. Winning these states meant fairly little in the Electoral College. Once the Solid South had been established after the end of Reconstruction, what the Democrats needed for a presidential victory was to win one or two large-population northern states. Even when Cleveland won the popular vote in 1888, this did not matter because the Democrats had failed to win a northern state such as New York, Ohio, or Pennsylvania.47 Democrats found that they were able to achieve presidential victories when there were political 45 Summers, Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion, p. 249. “Announcements,” The Waterville Mail, October 24, 1884, p. 1, (Microfilm). 47 Election of 1888, The American Presidency Project, (online resource) http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1888. 46 13 splits within the Republican Party, or when third party candidates took votes away from the Republicans. This happened in 1884, again in 1892 with the re-election of Cleveland and yet again in 1912 with the election of Woodrow Wilson.48 To attribute Cleveland’s victory solely to the “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion” statement of Burchard downplays the numerous other aspects of the 1884 presidential election. More importantly, this mindset also fails to recognize immense political trends that had their roots in the American Civil War, whose legacy would be felt for decades to come in American history. The results of the 1884 presidential election are a testament to this. 48 Election of 1912, The American Presidency Project, (online resource) http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1912. 14 Bibliography: Primary Sources: Cleveland, Grover. Letters of Grover Cleveland 1850-1908. Selected and Edited by Allan Nevins. Ed. Allan Nevins. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Riverside Press, 1933. "Democratic Party Platforms: Democratic Party Platform of 1884." Democratic Party Platforms: Democratic Party Platform of 1884. Web. 01 Nov. 2013. <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29583>. Knox, Thomas W. The Lives of James G. Blaine and John A. Logan. Hartford, Connecticut: The Hartford Publishing Company, 1884. The Republican Campaign Text Book for 1884. New York: Republican National Committee, 1884. "Republican Party Platforms: Republican Party Platform of 1884." Republican Party Platforms: Republican Party Platform of 1884. Web. 01 Nov. 2013. <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29626>. Newspapers: The Boston Globe The Boston Journal The Independent The New York Times The Waterville Mail 15 Secondary Sources: "1884 Presidential Election." 1884 Presidential Election. Web. 31 Oct. 2013. <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1884>. "1892 Presidential Election." 1892 Presidential Election. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1892>. "1912 Presidential Election." 1912 Presidential Election. Web. 2 Dec. 2013. <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showelection.php?year=1912>. Gyory, Andrew. Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1998. Healy, David F. "James G. Blaine." Statesmen Who Were Never President. Edited by Kenneth W. Thompson. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1997. 27-45. Nash, Howard P. Stormy Petrel: The Life and Times of General Benjamin F. Butler, 1818-1893. Rutherford, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1969. Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1932. Norgren, Jill. Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would Be President. New York: New York University Press, 2007. Russell, Charles Edward. Blaine of Maine; His Life and Times. New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1931. Seitz, Don C. The "Also Rans"; Great Men Who Missed Making the Presidential Goal. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1968. Stanwood, Edward. James G. Blaine: American Statesman. New York: Houghton-Mifflin, Riverside Press, 1906. 16 Stone, Irving. They Also Ran: The Story of the Men Who Were Defeated for the Presidency. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1943. Summers, Mark W. Rum, Romanism, & Rebellion: The Making of a President, 1884. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2000. Welch, Richard E. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas, 1988. 17