Chapter 5

advertisement

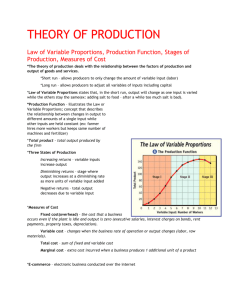

Chapter 5 COSTS AND PRODUCTIVITY 1. Opportunity Costs The correct measure of the costs of any action is what has been given up by taking that action instead of another. (Why accounting and law professors are paid more) The opportunity cost of any action— consumption, production, leisure, government spending—is the value of the next-best alternative lost. Opportunity cost is precisely defined not by any alternative but by the next-best alternative. The opportunity cost of any resource—land, labor capital, materials—is the payment that that resource would receive in its next-best alternative use. 1.1 Explicit and Implicit Costs When a firm requires resource it makes payments for the resources; the skilled mechanic gets a weekly paycheck; etc. An explicit cost (also called an accounting cost) is incurred when an actual payment is made for a resource. Firms also incur implicit costs in acquiring and using resources; no actual payments are made; no money changes hands, but these are real costs to the firm. An implicit cost is incurred when an alternative is sacrificed by the firm using a resource that it owns. 1.2 Economic Profits Economic profit equals the firm’s revenues minus its total opportunity costs (explicit plus implicit costs). A normal profit is earned when total revenues equal total opportunity costs. An economic profit is earned when total revenues exceed total opportunity costs. 2. The Short Run and Long Run The optimal (profit-maximizing) level of output depends on how opportunity costs change with the level of output. Business firms expand their volume of output by hiring or using additional resources. As more resources are employed, the opportunity costs of production increase. The opportunity cost of the resources used to produce output depend on their prices and their productivity. The higher the resource prices, the higher the opportunity costs of production. The lower the productivity of resources, the higher the opportunity costs of production. 2. The Short Run and Long Run – cont. Time plays a role in determining resource cost; some resources can be increased or reduced more rapidly than others. Variable inputs increase with output. Fixed inputs cannot be changed in the relevant time frame. Economists distinguish between the short run and long run when considering the time necessary to change input levels. 2. The Short Run and Long Run – cont. The short run is a period of time too short for plant or equipment to be varied. Additional output can be produced only by increasing the variable outputs, usually labor and material. The long run is a period of time long enough to vary all inputs and for firms to enter and leave the industry. The long run is not a predetermined amount of calendar time; a new assembly line may be installed in a few weeks. 3. Diminishing Returns Ricardo, an English economist (1500’s), noted that agricultural land was in fixed supply even though other factors of production like labor, could be increased, there were limits to the growth of agricultural output. As more variable inputs were added to the fixed amount of input, land, eventually these variable inputs would yield smaller and smaller additions to output. Why? As the fixed input became overcrowded with variable inputs, as more farmhands were added to already overcrowded farmland, their extra contribution to output would become smaller and smaller. 3. Diminishing Returns – cont. The marginal product (MP) of labor—or of any variable factor—is the increase in output that results from increasing the input by one unit. (Labor, output and Marginal product example) The law of diminishing returns states that as ever larger inputs of a variable factor are combined with fixed inputs, eventually its MP will decline. (Why wine is produced almost everywhere) 4. Short-Run Costs The behavior of costs in the short run reflects the law of diminishing returns. 4.1 Fixed and Variable Costs In the short run, some factors (such as plant and equipment) are fixed in supply; even if the firm wanted to increase them, it would not be possible in the short run; the cost of these fixed factors are fixed costs. Fixed costs (FC) do not vary with output: variable costs (VC) do. Total costs (TC) are fixed costs plus variable costs: TC = FC + VC. 4.1 Fixed and Variable Costs – cont. In the long run, all costs are variable and fixed costs are zero. In the short run, some costs are fixed. There is no way to change fixed costs; fixed resources have no alternative use; they are fixed and cannot be used elsewhere. Output can be expanded only by an increase in variable inputs and thus in variable costs. 4.2 Marginal and Average Costs Productivity and costs are inversely related. The higher productivity, the lower costs; The lower productivity, the higher costs. 4.2.1 Marginal costs TC = FC + VC Since fixed costs are constant, as output increases both total costs and variable cost increase by the same amount. Marginal costs (MC) is the change in total cost (or, equivalently, in variable cost) divided by the increase in output—or, alternatively, the increase in costs per unit increase and output (Q): MC = TC/Q = VC/Q. 4.2.2 Average cost While marginal costs look at the change in costs per unit change in output, average costs spread total, variable, or fixed costs over the entire quantity of output. Average variable cost (AVC) is variable cost divided by output. Average fixed cost (AFC) is fixed cost divided by output. Average total cost (ATC) is total cost divided by output, which also equals the sum of average variable cost and average fixed cost. 4.3 The Cost Curves FC + VC = TC (Panel A, Panel B example) FC/Q + VC/Q = TC/Q AFC + AVC = ATC The law of diminishing returns dictates that marginal costs must eventually rise as output expands. Marginal cost equals ATC and AVC at their minimum values. 5. Long Run Costs In the long run, enterprises do not have any fixed costs; all costs are available; the business is free to choose any combination of inputs to produce output. Once long run decisions are executed (the company completes a new plant), the enterprise again has fixed factors and fixed costs. In the long run, enterprises are free to select the cost-minimizing level of capital, labor, and land inputs; their decisions are based on the prices the firm must pay for land, labor, and capital. 5.1 Shift in Cost Curves See Acme Steel example 5.2 The Long-Run Cost Curve In the long run, all costs are variable; therefore, there is no distinction between long-run variable costs and long-run total costs—there is only long-run average costs. Long-run average cost (LRAC) is the average cost for each level of output when all factor inputs are variable. In the long-run, the enterprise is free to select the most effective combination of factor inputs because none of the inputs are fixed; the long-run cost curve envelops the short-run cost curves, forming a longrun curve that touches each short-run cost curve at only one point. 5.3 Economics and Diseconomies of Scale In the short run, the fact that some factors of production are fixed causes the short-run average total cost curve to be U-shaped. The law of diminishing returns does not apply to the long run because all inputs are variable. Why would long-run average costs (LRAC) first decline as output expands and then later increase as output expands even further? Firms experience first economies of scale, then constant returns to scale, and finally diseconomies of scale as output expands. 5.3.1 Economies of Scale The declining portion of the LRAC curve is due to economics of scale. Economies of scale are present when an increase in output causes average costs to fall. Workers are able to specialize in various activities; increase their productivity or dexterity through experience, and save time in moving from one task to another. 5.3.1 Economies of Scale – cont. Economics of scale occur because of the greater productivity of specialization in any of a variety of areas, including technological equipment, marketing, research and development, and management. As the output of an enterprise increases with all inputs variable; average costs will decline because of the economies of scale associated with increased specialization of labor, management, plant, and equipment. 5.3.2 Constant Returns to Scale Economies of scale will become exhausted at some point when expanding output no longer increases productivity. Constant returns to scale are present when an increase in output does not change average costs of production. 5.3.3 Diseconomies of Scale As the enterprise continues to expand its output, eventually all the economies of largescale production will be exploited and longrun average costs will begin to rise. The rise in long-run average costs as output of the enterprise expands is the result of diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of scale are present when an increase in output causes average costs to increase. 5.3.3 Diseconomies of Scale – cont. Diseconomies of scale can be caused by various factors: As the firm continues to expand, managers must assume additional responsibility, and managerial talents are spread so thin that the efficiency of management declines. The problem of maintaining communications within a large firm grows, and additional rules, regulations, and paperwork requirements become commonplace. As the output of an enterprise continues to increase, average cost will eventually rise because of the diseconomies of scale associated with the growing problems of managerial control and coordination. 5.4 Minimum Efficient Scale Firms and industries differ in their patterns of LRAC; they have different minimum efficient scales. The minimum efficient scale is the lowest level of output at which long-run average costs are minimized. Minimum efficient scale is an important determinant of industrial structure. In industries such as restaurants, commercial printing, etc., where firms reach their minimum efficient scale at low levels of output, the industry is populated by a large number of small firms. 5.4 Minimum Efficient Scale – cont. In industries such as automobiles and electricity generation, where minimum efficiency scale is not reached until there are very high volumes of output, the industry is populated by a small number of large firms. Minimum efficiency scale, therefore, plays an important role in determining the amount of competition in the industry. (Airbus versus Boeing example)