Buprenorphine in Medication Assisted Treatment

advertisement

Buprenorphine in Medication

Assisted Treatment (MAT):

Problem or Solution?

Quintin Thomas Chipley, M.A., M.D., Ph.D.

and

Greg Jones, M.D., ABFM, ABAM, MRO

Prepared for CAPTASA 2016

DISCLOSURES

Neither presenter has any financial interest in any mode of

treatment as discussed in this presentation.

Quintin Chipley is employed at the University of Louisville as a

counselor to students at the Health Science Center. The U of L

is gracious to allow Chipley latitude to pursue professionallyrelevant endeavors outside of his work duties, but the

university should not be considered responsible for the

opinions and conclusions offered in this presentation.

Greg Jones is the medical director of the Kentucky Physicians

Health Program. Although that organization continues to be a

long-standing supporter of CAPTASA, and also supports Dr.

Jones’ relevant professional endeavors exterior to his

employment, the KPHF should not be considered responsible

for the opinions and conclusions offered in this presentation.

OVERVIEW

• HISTORY of BUPRENORPHINE and its use in

Medication Assisted Treatment1

• Problems observed in the research-and-policy

literature regarding Buprenorphine MAT

• Clinical anecdotes suggesting problems which

need future research

• Preliminary report on descriptive statistical data

gathered from The Healing Place, men’s and

women’s campuses, Louisville, Kentucky.

1

The material for the history of buprenorphine is taken from an excellent, well-balanced,

and carefully researched article: Nancy D. Campbell and Anne M. Lovell. “The History of the

Development of Buprenorphine As an Addiction Therapeutic.” Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences. Issue: Addiction Reviews. 1248. 2012. 124-139. Referred to in the

following as Campbell and Lovell, 2012.

PART 1

HISTORY of BUPRENORPHINE

and Its Use in

Medication Assisted

Treatment

Buprenorphine:

A Tale of Markets, Labs, and Laws

Five Periods of Development, Pitch, and Legislation

1) 1966- 1978: Marketplace: Reckitts (a British household-chemicals manufacturer)

search for a non-addictive opiate analgesic which they hope can be nonprescription.

They discover buprenorphine in 1966 and start human trials.

Laboratory: In 1975, buprenorphine garners interest among U.S. researchers as a

possible addiction treatment before approved as analgesic use in U.K. in 1978.

2) 1978- 1982: Market: Poor sales as an injectable analgesic for acute pain.

Lab: U.S. researchers classify it as partial agonist/ antagonist within the larger groups

of antagonist opioids. These researchers want to find a “magic bullet” antagonist.

3) 1982 –1993: Market: sublingual for acute pain introduced, but Reckitts has been

losing interest due to weak sales; sells most marketing rights to other companies.

Lab: U.S. researchers want to make it an addiction treatment. French clinicians are

already using it off-label as a “harms reduction” addiction treatment.

4) 1993 - 2002: Market, Lab, and Law mingle: search for new indications (e.g. refractory depression (not labelled for this use yet, but pay attention to the

implications); treating opiate addiction; France officially allows use for addiction

treatment. Drug Abuse Treatment Act (DATA) of 2000 in U.S. allows outpatient office

treatment of addiction unlike specially licensed clinics required for methadone.

5) 2002 to the present: Market, Lab and Law merge: labelled use for treating “opiate

addiction” gains FDA approval in 2002, to fill the demand created by DATA 2000.

The first period:

1966-1978

• Buprenorphine, a semisynthetic opioid derived from

thebaine, is isolated in 1966 by the British company

Reckitt and Coleman, now named Reckitt Benckiser.

They had hoped to find an analgesic for acute pain that

would be as effective as morphine, but non-addictive

and eligible for over-the-counter sales.

• Buprenorphine entered human trials in 1971 and was

approved for market in the United Kingdom in 1978.

The British company began supplying buprenorphine

as a research drug to the U.S. A.R.C. in Lexington, KY. In

1975, strong interest in buprenorphine as a possible

drug with which to treat addiction began at that

location.

Second Period: 1978-1982

• The injectable form of buprenorphine failed to

secure consistent choice-of-use among physicians

because the suppression of acute pain was poor.

• Even at prescribed doses, the medication proved

to be addictive, though this clinically documented

fact contradicted conclusions drawn from a 1978

study (see next slide).

• A sublingual formulation was introduced in 1982.

Second Period: 1978-1982

(Continued)

• “In 1979, Jasinski classified the narcotic antagonists into three groups: (1)

compounds that produced agonistic effects that do not resemble

morphine (nalorphine and cyclazocine), (2) compounds that do not

produce agonistic effects (naloxone and naltrexone), and (3) antagonists

that produce agonistic effects that resemble those of morphine because

they are also partial agonists of morphine. By then, six category 1 narcotic

antagonists had been introduced as analgesics with low abuse potential.

According to Jasinski’s scheme, propiram and buprenorphine fit category

3. Interest shifted to these ‘partial agonists of the morphine type,’ which

did not constitute a homogenous class due to their intrinsically different

capacities for producing euphoria, sedation, and psychotomimetic

effects.” (Campbell and Lovell, 2012, p. 132; red-font emphasis added by presenter.)

PAY ATTENTION TO THE ASSUMPTION OF “intrinsically different.” Also, this is when Jasinski begins citing

his 1978 study to declare “it [buprenorphine] produced ‘very little physical dependence’ even with

chronic administration .” (Campbell and Lovell, 2012, p. 132.) There is a real problem (though we do NOT

consider it an intentional misrepresentation) with the way Jasinski interpreted the data reported in

Jasinski, D.R., Pevnick, J.S. and Griffith, J.D., “Human Pharmacology and Abuse Potential of the Analgesic

Buprenorphine: A Potential Agent for Treating Narcotic Addiction,” Archives of General Psychiatry, 35,

April 1978, 501-516. In that study, only three subjects completed the active treatment arm of the study,

and the primary measure of “physical dependence” was degree of dysphoria created when administered

naloxone as a reversal antagonist. Here is the problem: naloxone and buprenorphine are so similar in

avidity for mu-receptor sites that the full antagonist naloxone is a poor competitor against buprenorphine

compared to the way naloxone molecules can dislodge morphine or heroin from receptors and then

defend against their return to reoccupy the receptor.

Third Period:

1982- early 1990’s

• The injectable forms and the sublingual forms of

buprenorphine were available but not much-used for

analgesia. By the early 1990’s, French physicians began

using the sublingual forms off-label to reduce needlesharing among addicts with the goal of reducing HIV

infections.

• U.S. government researchers with the famous

“Narcotics Farm” in Lexington, KY had moved to

Maryland as the ARC after 1979 (and was renamed the

NIDA Intra Mural Research Program in the 1990’s.)

Donald Jasinski was one of these scientists.

Third Period:

1982- early 1990’s (CONTINUED)

In a 1983 meeting of the Committee on Problems of Drug

Dependence (CPDD), a group under the National

Academy of Sciences, meeting,

“Jasinski spoke to buprenorphine’s advantages over

naltrexone, noting that his subjects liked buprenorphine

better, and ‘felt comfortable on it. The induction of a

feeling state that they found salient following

buprenorphine was certainly there. . . Most of our

subjects told us that it was, in fact, the most reinforcing

drug that they had ever used’ (p. 95). Despite this

caution, buprenorphine was offered as a ‘safe and

effective mode of pharmacotherapy for heroin

addiction.’”

Campbell and Lovell 2012, p. 133. Font emphasis added by presenter.)

Third Period:

1982- early 1990’s (CONTINUED)

“But the shift from research to industrial drug development for addiction

treatment took off at the intersection of two trajectories: formal interest on

the part of NIDA and a change of orientation within Reckitts. In 1989, the U.S.

Congress mandated that a Medications Development Program be established

in NIDA. The following year, NIDA established the Medications Development

Division (MDD) to develop close working relationships between academia,

the pharmaceutical industry, and government agencies, including the FDA, so

as to develop and evaluate addiction treatment medications to the point that

they could go through the FDA approval process.[…. ]The time was propitious

for Reckitts, as well. Disappointed with its analgesia business, the company

had contracted out buprenorphine commercialization to numerous

companies worldwide and had abandoned ethical1 drug development in the

early 1980s.” (Campbell and Lovell, 2012, p. 134. Emphasis added)

1

“Ethical” is used here in a very specific sense of “for human use.” It does not mean “in accord

with guiding principles of acceptable behavior and judgement.” Reckitts had been mostly a

household-chemical (that is, Lysol, etc.) manufacturing company. Their disappointing foray into

analgesic medication had burned them financially, and they had returned to their origins. They

probably would have kept their products under the kitchen cabinet -- and out of the medicine

cabinet -- if NIDA had not aggressively courted them to reconsider their own product,

buprenorphine, for the new indication of opiate-addiction treatment.)

Fourth Period:

1993-2002

“In 1993,MDD also approached Reckitts about formalizing

their already existing mutual interest in developing

buprenorphine for addiction treatment. NIDA was

interested in buprenorphine by itself and in combination

with naloxone (to prevent diversion).1 Reckitts was NIDA’s

obvious choice for a Cooperative Research and

Development Agreement (CRADA), as another company

would have had to conduct safety and toxicology studies

from scratch for a new indication.” Campbell and Lovell 2012, p. 134.)

1Adding

naloxone to methadone as a diversion-deterrent had been proposed

many years before, though it had not been actively pursued because officials felt

that confining methadone to dedicated, clinic-only-distribution would blunt

diversion sufficiently. Their idea to add naloxone as diversion prevention was

theory-driven rather than experimentally well-demonstrated, either for

methadone or for buprenorphine. The theory presupposes that all brains basically

respond similarly. If you believe that brains prone to addiction work differently

than those not prone to addiction, the theory will not be convincing.

Fourth Period:

1993-2002 (CONTINUED)

In 1994, France and some countries in Asia approve

buprenorphine for labeled use in opiate addiction

treatment as an attempt to reduce HIV infections

from shared needles. The use is explicitly

understood as “harms reduction.”1 Reckitts begins

buying back it rights to the drug. The same years,

U.S. gave Reckitts the CRADA approval, and

included a 7 year “orphan drug” marketing

protection based entirely on economic risk. This is

the first medication granted “orphan” status on an

economic argument.

1It

is crucial to distinguish “harms reduction” and “recovery from

addiction. “ Choices that might be good for the first goal can very well

be bad for the second goal.

Fourth Period:

1993-2002 (CONTINUED)

Until this time, buprenorphine was only a Schedule 5 drug (i.e. lowest

perceived danger). An interesting “contest” (i.e. – fight) between two

U.S. government agencies emerged. The DEA wanted it to put it on

Schedule 2, which would have effectively precluded any simple outpatient use. NIDA, however, was helping Reckitt Benckhiser lobby

Congress to allow physicians with extra-training to treat addicts at

regular outpatient office visits. The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of

2000 (DATA of 2000) allowed such trained physicians to apply for a DEA

exemption (that is the “x” on a DEA license number), buprenorphine

was placed on Schedule 3 around 2001, and in 2002 the FDA approved

the indication for opiate addiction treatment. The American Society of

Addiction Medicine (ASAM) began voicing strong approval of

buprenorphine for addiction-treatment beginning in 1998. ASAM was

entirely supportive of DATA of 2000, two years before buprenorphine

could be legally used by any physician outside the few approved

experimental-trial locations.

Fifth Period:

2002 - Present

Although buprenorphine has moved back into the market as an analgesic

(now for chronic pain) the strongest market, however, is for MAT. There has

been an explicit shift from a) use as a short-term (a few weeks) “step-down”

detox agent for physiological opiate dependence to b) use as a long-term (18

to 24 months; perhaps lifetime) for a mixed population of with addiction who

are mostly polysubstance-abusing addicts. An FDA advisory committee

recommended on January 12, 2016 that an implanted buprenorphine device

(6 month longevity per implant) be approved fully by the FDA for the purpose

of MAT 1. This form awaits final FDA approval. Veterinarians use the injectable

formulation for animal analgesia.

The literature -- both primary journal articles and policy statements for bestpractices – on MAT with buprenorphine tends to be unclear as to whether the

goal for MAT is eventual abstinence-based living for the individual patient or if

it is “harms reduction” for the population as a whole.

1Szabo,

Liz. “Panel recommends FDA approve implant to treat opiate addiction.“ USA Today. January 12, 2016.

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/01/12/implant-aims-help-addicts-stop-using-heroin-prescription-painkillers/78677618/

Accessed January 13, 2016.

Fifth Period:

2002 – Present - Continued

• Special training for prescribing physicians was created as an eight-hour

course.

• The DATA 2000 federal law restricted states from passing legislation that

forbade office practice on the basis of the opiate nature of the drug.

• The restricted case-load in any one physician’s practice was originally set

at 10 patients, was almost immediately increased to 30 patients in the first

year with 100 patients allowed after demonstrating a year’s experience.

Prescribers are now petitioning for the removal of all patient-load caps on

practice enrollment.

• Patients are usually seen once a month

• Payment for buprenorphine MAT was originally about $700 per month,

usually fee-for-service in cash. The cost now tends to be about $250 per

month. Some states have modified laws to require that prescribing

physicians accept insurance, and this requirement seems to pass muster

with the DATA 2000 federal law.

• Medicaid pays for much of the drug cost.

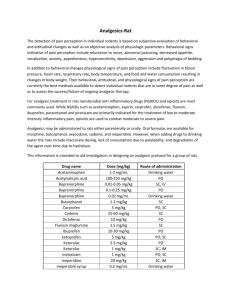

TOP 5 KY MEDICAID DRUG COST 2013:

Suboxone is 2nd at 17 million dollars

Script

Count

Member

Count

Quanty

Dispensed

Days

Supplied

Ranking by

Ranking by Member

Script Count Count

Ranking by

Total Spend

Drug Name

Total Spend

ABILIFY

$ 24,906,824.45

38737

6305

1163656.25

861954

1

85

139

SUBOXONE

$ 17,038,816.62

68863

6264

2317728

457642

2

46

140

METHYLPHENIDATE ER

$ 14,538,070.11

104687

17038

3376217

2236036

3

23

62

ADVAIR DISKUS

$ 13,124,576.01

50231

12661 3008171.635

991852

4

67

82

VYVANSE

$ 12,513,247.64

74453

11598

1380065

5

39

90

2213005

Part 2

Problems Observed In

the Research-and-Policy Literature

Regarding Buprenorphine MAT

Philosophies and Mental Health Science

Pure science, supposedly, is driven only by quantifiable data that is

interpreted as true information. The lens of interpretation, however, is

ground by philosophies, and philosophical theory harbors bias. We can

neither safely abandon the strengths of science nor ignore its weaknesses.

1) In the post-WW II years, researchers had immense trust in the ability of

science to correct human ailments with pharmaceutical agents. Advances in

medications to help treat everything from bacterial infections to depression

and psychotic disorders contributed to the optimism. But this burgeoning

optimism also led to the period of the 1960’s when dangers were minimized

or missed; a time, for example, when amphetamines and benzodiazepines

were freely distributed not only with little concern for addiction but even

with bold assertions that addiction was not possible.

2) In the post-WW II years, and especially by the 1960’s, psychology and

psychiatry in the U.S. were dominated by strict behaviorism’s learning

principles as discovered by B.F. Skinner. This psychology model has, as a

foundational premise, the notion that brains of similar intelligence will be

uniformly responsive to punishers and rewards in learning and unlearning

behaviors. It was not until Social Learning Theory (Albert Bandura in the early

1960’s) and Cognitive-Behavioral Theory (Aaron Beck in the later 1960’s and

early 1970’s) did a significant role for affect (i.e. – emotion) in learning arise.

Philosophies and Mental Health

Science- Continued

3) Campbell and Lovell, 2012, clearly describe a decadeslong tradition of very strong hopes among the U.S.

“Narcotics Farm” researchers that some opiate

antagonist would be the “Holy Grail” of addiction

treatment. This hope seems to be the only reasonable

explanation of Jasinski’s choice to classify buprenorphine

under the heading, “antagonist,” despite the clearly

established knowledge that the medication showed

morphine-like agonist action. We are not attributing

intentional misrepresentation as his motive, but we do

suspect that clear science was obscured by the

laboratory’s philosophical agenda that purported good

intentions.

Some Background on Discoveries

• Watson and Crick first described the mechanism of

inheritance, Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, in 1953.

• Donald Goodwin published in a series of four articles1

in the early 1970’s the definitive proof from the

“natural laboratory” in Denmark using adoption

records that alcohol addiction is more strongly

predicted by manifestations in the biological than by

manifestations in the adoptive environment.

• The “Decade of the Brain” of the 1990’s used the newly

improved non-invasive, neuro-imaging techniques to

demonstrate distinct differences in living-brain function

for addicts versus non-addicts.2

1Summarized in

Goodwin, Donald. Is Alcoholism Hereditary? New York : Oxford University Press, 1976. Print.

a more recent article that will provide in the reference list a good guide to this advance in imaging to addiction, see

Goldstein, Rita Z and Nora D. Volkow. “Dysfunction of the Prefrontal Cortex in Addiction: Neuroimaging Findings and Clinical

Implications.” Nature. 12. November 2011. 652- 669. Print.

2For

Implications for the Buprenorphine

MAT Researchers

The major researchers for developing addiction-treatment

applications of buprenorphine were all educated at the

graduate study level before these advances had made much

of an impact on their notions about neuropharmacology of

addiction. A rough summary of the implications might be:

1) They tended to think, “All brains are basically the same,

and all brains train in the same way,”

2) They did not have the advantage of understanding the

impress of genetic load,

3) They had not absorbed the implications of the role that

affect (i.e. - emotion) plays in learning, and

4) They were of the generation of medical scientists who

were entranced by a wide array of proposed

pharmacological solutions.

BLUNT PROBLEM: Opiate Receptors “Burned”?

There is a notion that opiate addicts “burn out” their mu

receptors for the remainder of their life (i.e. – they will

always be deficient in ability for endogenous opioids and

encephalin substances to sooth the brain). This notion

has no credible foundation in any study we have found.

We are open to reviewing such if we can be pointed to

the sources. There are studies that show, for example,

that extensive methamphetamine-use permanently

truncates neuronal axons beyond repair,1 but the mureceptor “burnout” hypothesis does not seem to have

similar hard-data based on micrographs of post-mortem

neurons or based on fluorescent antibody studies.

1Gold

MS, Kobeissy FH, Wang KK, Merlo LJ, Bruijnzeel AW, Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. “Methamphetamine- and trauma-induced brain

injuries: comparative cellular and molecular neurobiological substrates.” Biological Psychiatry. 2009 Jul 15;66(2):118-27. PMID:

19345341

Blunt Problem: No Euphoria?

The buprenorphine literature continues to state that the drug causes little euphoria

because of the “ceiling effect” that occurs when the antagonist action trumps the

agonist action. The ceiling effect for buprenorphine alone (i.e. – when no sedativehypnotic drug like a benzodiazepine or alcohol is also present) is true for respiratory

suppression (brain-stem/ mid brain area). But this effect is not generalizable to all

parts of the brain; nor to polysubstance abusers.

THE PROBLEM is TWO FOLD:

• First, even the researchers know that naïve subjects can, and do, get high on

buprenorphine. It is true that an active heroin or Rx opiate addict will not get

much euphoria from buprenorphine, but a detoxed-addict or a first-time user will

and does get high. BUPRENORPHINE IS A DRUG OF REWARD.

• Second, IT IS A DRUG OF REWARD primarily because of the dopamine system, not

the nociceptive system. The major mu-receptor activity in the brain associated

with pain-control does not cause a “high.” Reduction of pain and induction of

euphoria are different phenomena. Opiate-receptors on interneurons in the

ventral tegmental area normally keep dopamine neurons from firing easily, but

when an opiate agonists settle on them, those interneurons stop inhibiting

dopamine release and a dopamine surge occurs. For 85% of the population, this

action may not be such a big concern because those people have a relatively

robust dopamine-reward system. They are “normals.” For persons who are

however predisposed to addiction genetically and, very possibly, epigenetically,

this action is serious. Introducing the predisposed addict’s pleasure-reward system

to any opiate agonist will likely trigger the phenomenon of craving.

Blunt Problem – Comparison Studies?

Articles that report on buprenorphine MAT tend only to compare it to other types of

MAT (clonidine, for example). The studies have not compared long-term use of

frequently-administered buprenorphine as MAT to long-term participation in

Abstinence-Based, peer-supported, frequently-attended programs such as 12 Step

Recovery. In fact, the presence of such “highly motivated subjects” as found in 12

Step Recovery would exclude them from a comparison-study because the MAT

comparison group would not be expected to show such motivation. The one study

which tried to compare buprenorphine-MAT to psychosocial therapies (i.e. variations of “talk therapy”) has been withdrawn from the field and the original

authors now concur that the study lacked sufficient data from which to draw any

conclusions.1 The studies most often measure success simply as “retention in

treatment” (i.e. – subjects show up for a longer period of time for some treatment).

The articles frequently generalize conclusions to populations not yet tested.

Examples:,1) results from MAT for Prescription opiate addicts is generalized to apply to

heroin addicts. 2) Results from studies about detoxification are generalized to longterm or life-time maintenance. 3) Results from opiate-only addicts are generalized to

polypharmacy addicts.

Mayet S, M Farrell, M Ferri, L Amato, M Davoli, “Psychosocial treatment for opiate abuse and dependence (Review).”The

Cochrane Library. 2004: 4. Reprint. 2010.

1

Blunt Problem – Harms Reduction vs.

Personal Recovery?

The confusion of the two different goals -- harms reduction and personal

recovery – in the research literature has bled into public policy pressures and

mandates.1 Harms reduction has as its main goal protection public interests

from addicts’ behaviors. Personal recovery has traditionally focused on an

individual finding a way to be abstinent from mind-altering drugs. The two

domains overlap, but they are not identical. As buprenorphine MAT advocates

amplify claims that this approach is evidence-based, three problems emerge.

1) There is no evidence comparing Buprenorphine MAT to Abstinence-Based

Recovery. Both approaches have believers, but neither side has controlledstudy evidence. NEITHER SIDE. 2) The Harms Reduction approach to social ills

has been quickly transformed into an Drug-substitution-Based Personal

Recovery, but this transformation has not paid attention to a real issue of

HARMS PROMOTION among a very vulnerable section of the population. This

vulnerable segment comprises the 8 to 15 % of the humans who are

predisposed to any-and-all addictions. These people are very likely 1) to have

predictive family histories and they are very likely 2) to exhibit polysubstance

abuse profiles. They do not usually get better on buprenorphine and they

often abuse buprenorphine (see study results below). They sometimes

transition from buprenorphine to heroin.2 - CONTINUED NEXT SLIDE

Blunt Problem – Harms Reduction vs.

Personal Recovery? - Continued

This vulnerable population -- many who have failed buprenorphine MAT in

the past – can find centers where, with sufficient motivation on their part and

with sufficient shielding from exposure to all drugs of reward on the part of

the center administrations, they can learn a design for living which allows

them to pursue abstinence-based personal recovery. Recent Public Policy

decisions and case-law findings increasingly attempt, however, to force such

abstinence-based-recovery centers to include in their case-loads participants

who choose buprenorphine MAT. If this trend gains power and force, it will

severely compromise the recovery-milieu of abstinence for those who choose

to pursue abstinence. A “clean” environment and a shared communal

experience is crucial for participants who are motivated to remain clearly

abstinent of all mind-altering substances.

1Vestal,

Christine. “In Drug Epidemic, Resistance to Medication Costs Lives.” Stateline: Pew Charitable Trust. January 11, 2016.

http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/01/11/in-drug-epidemic-resistance-to-medication-costs-lives

Accessed January 13, 2016.

2Weiss,

Roger D., Jennifer Sharpe Potter, Margaret L. Griffin, Scott E. Provost, Garrett M. Fitzmaurice, Katherine A. McDermott, Emily N. Srisarajivakul,

Dorian R. Dodd, Jessica A. Dreifuss, , R. Kathryn McHugh, Kathleen M. Carro. “Long-term outcomes from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials

Network Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 150 (2015). 112–119.

{PRESENTERS’ COMMENT: THIS STUDY IS PUBLISHED BY A TEAM WHERE THE LEAD RESEARCHER DISCLOSES FINANCIAL TIES TO RECKITT BENCKISER. EVEN

THOSE WHO STRONGLY SUPPORT THE WIDE USE OF BUPRENORPOHINE AS M.A.T. HAVE ACKNOWLEDGED THAT PRESCRIPTION OPIATE ADDICTS WITH NO

PREVIOUS HEROIN USE HISTORY HAVE ADVANCED TO HEROIN AFTER EXTENDED TREATMENT WITH BUPRENORPHINE.]

Blunt Problem – Is Ancillary

Counseling Support is Erratically

Advised and/ or Monitored?

Practice guidelines suggest that buprenorphine prescribers encourage

patients to engage in some form of non-medication psycho-social

therapy or peer-support. The buprenorphine MAT advocate industry

that has set those guidelines, however, 1) has not, determined by

random-assignment, controlled measurement studies which ancillary

therapy modality to encourage, 2) the prescribers have generally not

been held accountable for their patients’ failure to continue with such

ancillary treatment, and 3) the outcome-goal (e.g. - Eventual

buprenorphine MAT cessation with continued opiate abstinence?

Lifetime continuation of buprenorphine MAT with lifetime abstinence

from all other opiates? Eventual buprenorphine MAT cessation with

subsequent abstinence from alcohol and all drugs-of-reward?) are not

defined. (See study results below)

Blunt Problem – Is There Agreement on

Advice Given for Duration of

Buprenorphine MAT?

Practice varies from a 7 day, detox administration to a recommendation of

life-time maintenance. Consider Reckitts response to journalist:1

“Has RBP written a protocol for titration off of the medication SUBOXONE®

Film or SUBUTEX® (buprenorphine HCl) Sublingual Tablet? If not, why?”

"No. Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc. believes there is no “one-sizefits-all” approach to opioid dependence treatment, and the company is not

aware of an established guideline or protocol for titration. The decision to

discontinue therapy with SUBOXONE® Film after a period of maintenance

should be made as part of a comprehensive treatment plan. Patients seeking

to discontinue treatment for opioid dependence should be advised to work

closely with their healthcare provider on a tapering schedule and should be

apprised of the potential to relapse to illicit drug use associated with

discontinuation of opioid agonist/partial agonist medication-assisted

treatment.“

1Roberts,

Dawn. “So You Thought You Could Get Off Suboxone?” The Fix: Addiction and Recovery,

Straight Up. September 04, 2014. https://www.thefix.com/content/hard-to-kick-suboxone?page=all .

Accessed January 13, 2016. Red font emphasis added by presenters.

Blunt Problem – Diversion Has

Increased

“2014 NFLIS Finds Nearly Three Times More Buprenorphine Than Methadone Reports

The National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) collects drug test results

from law enforcement-encountered drug items submitted to and analyzed by state

and local forensic laboratories across the country. NFLIS data can provide valuable

information about trends in the drugs seized by U.S. law enforcement. In 2014, the

number of NFLIS reports for buprenorphine reached a high of 15,209, almost three

times the number of methadone reports (5,559). Buprenorphine reports increased

from 90 in 2003 (one year after buprenorphine was approved to treat opioid

dependence) to 15,209 in 2014. In contrast, methadone reached a peak of 10,016

reports in 2009, and has since decreased each year. In 2014, the Northeast had the

highest rate of buprenorphine reports (9.79 per 100,000 persons aged 15 or older),

while the West had the lowest rate (2.09 per 100,000 persons). More information

about buprenorphine can be found in the CESAR FAX Buprenorphine Series, available

online at http://go.umd.edu/cesarfaxbuprenorphine .“

CESAR FAX Volume 24, Issue 13, found at:

http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/cesarfax.asp

Blunt Problem – Diversion Has

Increased

KENTUCKY MEDICAL EXAMINATION OFFICER’S

REPORT - 2014

Kentucky Resident Drug Overdose

Deaths by Drugs Involved (High

volume drugs)

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

ALPRAZOLAM

ETHANOL

HYDROCODONE

2011

2012

OXYCODONE

2013

2014

HEROIN

FENTANYL

Kentucky Resident Drug Overdose

Deaths by Drugs Involved (Lower

volume drugs)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

BUPRENORPHINE

GABAPENTIN

2011

METHAMPHETAMINE

2012

2013

2014

THC

% Change Shown on KY MEO Toxicology Reports from 2013 to 2014

Fentanyl

Hydrocodone

Gabapentin

Buprenorphine

Heroin

Methamphetamine

Ethanol

Alprazolam

0.0%

100.0%

200.0%

300.0%

400.0%

500.0%

600.0%

Part 3

Clinical Anecdotes

Suggesting Problems

Which Need Future Research

Anecdotes CAN Lead to Data

Although the “plural of anecdote is not data,” a

deaf ear to anecdotes is most certainly a form of

“contempt prior to investigation.” Testable

hypotheses in medicine and mental health are

derived by careful attention to the signs and

symptoms of patients in the clinical settings, and

both treatment professionals and the patients in

addiction-recovery settings have been reporting

important things that deserve investigation.

“Is Dose Selection Supported?”

Criteria for choosing an induction-dose criteria

have never been well established by

randomized, controlled trials. This problem has

led to some patients, especially patients with

recent physiological addiction to prescription

opiates but with current remission from acute

withdrawal, to experience the induction dose as

the strongest “high” ever experienced in their

drug-use career. Avoiding iatrogenic euphoria

would seem to be an important goal.

“Is There An Increased Risk of

Depression?”

Some treatment center professionals have noted that

their participants who have been placed on

buprenorphine MAT seem to be more likely to exhibit

treatment-resistant major depression when compared to

the depressive episodes exhibited by recovering

participants not on this same MAT. The question of

possible iatrogenic depression requires investigation,

especially since an increasing trend has emerged to

suggest multiple-year to life-long adherence to MAT.

See also, Scherrer, Jeffrey F. Joanne Salas, Laurel A. Copeland, Eileen M. Stock, Brian K. Ahmedani, Mark D. Sullivan, Thomas Burroughs, F.

David Schneider, Kathleen K. Bucholz, and Patrick J. Lustman. “Prescription Opioid Duration, Dose, and Increased Risk of Depression in 3 Large

Patient Populations.” Ann Fam Med January/February 2016 14:54-62; doi:10.1370/afm.1885.

“CONCLUSIONS Opioid-related new onset of depression is associated with longer duration of use but not dose. Patients and practitioners

should be aware that opioid analgesic use of longer than 30 days imposes risk of new-onset depression. Opioid analgesic use, not just pain,

should be considered a potential source when patients report depressed mood.”

With each incremental increase (one month, two months, and three months duration), the risk on new-onset depression increased. This study

did NOT include any patients on buprenorphine (whether for pain treatment or for addiction treatment), but buprenorphine is an opioid

which originated as analgesic, has maintained that analgesic indication, has expand formulations for that analgesic application. This question

deserves to be answered so that patients who are considering the offer of many months or lifetime treatment can have a true informed

consent.

“Is Cessation of Buprenorphine More

Difficult Than Other Opiate Cessations?”

Anecdotes1 for participants in buprenorphine

MAT who decide to taper-off and then to quit

the extended maintenance report that the

withdrawal and cessation is more difficult than

even other MAT agents such as methadone. If

this is established by controlled research, proper

Informed Consent would need to be modified to

warn patients of this probability.

Roberts, Dawn. “So You Thought You Could Get Off Suboxone?” The Fix: Addiction and Recovery,

Straight Up. September 04, 2014. https://www.thefix.com/content/hard-to-kicksuboxone?page=all . Accessed January 13, 2016.

“When Should the Patient Plan to Stop

Buprenorphine MAT?”

As noted above, the research literature itself

does not give clear statements to this question.

Patient anecdotes suggest that prescriber

practices vary widely and wildly. Some patients

cannot even recall having been told by the

prescribers ANY target cessation goal.

“Possible Overdose Morbidity/Mortality

When Mixed with Sedative-Hypnotics?”

As shown in Section 3 above, states are including

buprenorphine (and the metabolite

norbuprenorphine) in toxicology screens and

reports. What is lacking so far is an analysis which

sorts out the overdose deaths which show when

buprenorphine is only present with any sedativehypnotic (e.g. – alcohol, benzodiazepines,

barbiturate)[ that is, when other well-known

mortality-associated opiates are absent.

“Extra Challenge Managing Overdose

in the ER?”

Emergency Department physicians already report that treating an

acute buprenorphine overdose by administering the reversal

(antagonist) agent naltrexone is difficult. Acute opiate overdose

treatment is initiated on history (if known) and clinical symptoms

(pupil size, respiration rates, etc.) and begins before lab results are

returned. Even then, common lab panels have not included

buprenorphine. In the first hour or two after naltrexone

administration, the patient’s signs improve, but these revert to the

poor levels of first presentation because buprenorphine molecules will

successfully compete against naltrexone to return to receptor-sites

before the liver detoxifies the plasma-levels of circulating drug.

Emergency Departments are busy places, and a suddenly (and

unexpectedly) “crash” of a previously stabilized patient is harrowing for

all concerned.

“What Social/Financial Burdens Are

Created by Diversion?”

Many participants in legally prescribed buprenorphine MAT report that

they procure their one-month supply from a pharmacy, they sell to

street-buyers a large portion (perhaps three-fourths) of the supply in

order to get money to purchase on the street opiates of preference

(diverted pain pills or heroin), hold back a portion (perhaps one-fourth

of the supply) for personal back-up use to stave of “drug sickness” in

the case that they cannot get a opiate of choice due to “dry spells” in

supply or lack of money.

This becomes a social financial burden because the purchase-price for

the legitimate prescription is often funded by others – sometimes

family members, but very often by Medicaid dollars.

When this occurs, Medication Assisted Treatment has become

Medication Facilitated Addiction, and the required capital for this form

of diversion is actually a diversion of dedicated health-care dollars. The

financial impact on public health care deserves study.

PART 4

Preliminary Report

on Descriptive1 Statistical Data

Gathered from The Healing Place,

Men’s and Women’s campuses,

Louisville, Kentucky.

1These

data are descriptive and not predictive according to standard use of those two terms

in inferential statistics. The subjects are drawn from a single cohort of a naturally-occurring

social setting. There is no random assignment to varied and controlled treatment

conditions. Having stated this fact clearly, we unapologetically hold the opinion that the

careful attention to these kinds of descriptions can help addiction-treatment professionals

and policy-developers understand more accurately the experience of these sorts of

subjects in this type of condition.

PARTICIPANT GENDER

120 Male

112 Female

TOTAL 232

PARTICIPANTS’ DRUGS OF

PREFERENCE

Subjects named three drugs in decreasing preference. The

drugs were coded in the classes of Heroin, Prescription

opiates, Alcohol, Benzodiazepines, Stimulants, Cannabis, and

Hallucinogens. Responses were searched to count the number

of times when either Heroin or Prescription Opiates occurred,

showing:

ZERO= 31% 1 time= 46% 2 times= 20% 3 times= 3%

(Background and Interpretation: Of the 232 subjects, about one-fourth were

almost exclusively alcohol users, or alcohol-and-non-opiate drug users. This

group did not have much opiate history or interest. Of the other subjects,

opiate-abuse was strong, but “opiate-only” users were extremely rare

(essentially only 3%). The opiate-addicts, therefore, in this setting are also

polysubstance abusing/ addicted.)

PARTICIPANT Self-Diagnosis

(N = 223, not 232 because

9 protocols failed to ask)

ADDICT:

48,

ALCOHOLIC:

66,

ADDICT AND ALCOHOLIC: 109,

NEITHER:

0,

or 22%

or 29%

or 49%

or 0%

History of buprenorphine use

(N = 232)

Had used buprenorphine

Had not used buprenorphine

146, or 63%

86, or 37%

Of Those Who Had Used

Buprenorphine (n = 146),

Those Who Used It ONLY WITH Prescription:

5, or 3.5%

Those Who Used It ONLY WITHOUT Prescription:

101, or 69%

Those Who Used It WITH AND WITHOUT Prescription:

40, or 27.5%

146 had used buprenorphine

(both circles combined)

101 only used

without Rx

(light blue

“C-shaped”

portion of

large circle)

146 had used

buprenorphine

(both circles

combined)

101

No

40

RX

=

141

Rx=45

45 had access by

Rx. (small circle).

Of them, 40 used

sometimes with

an Rx and

sometimes

without an Rx

5 (dark blue portion

of the small

circle). 5 of them

only used with an

Rx (light blue

“fingernail” of

small circle).

Intentional Euphoria-Seeking by

Use of Buprenorphine

Those who did so who only used without prescription

(n= 101):

77, or 76%

Those who did so who used both with and without

prescription (n= 40):

34 or 85.2%

Those Reporting Prescription-OnlyAccess to Buprenorphine (n=5) Who

Reported Taking Other Drugs or

Alcohol with Their Rx Buprenorphine

to Get a High

4, or 80%

Those Who Reported They Had Used

Buprenorphine to Get Through Rough

Days Until They Could Get Their

Preferred Drug of Choice

(“Bridge Use”)

Those who only used without prescription (n = 101):

79, or 78%

Those who used with and without prescription (n = 40):

34, or 85%

Ancillary Treatment-Advice from

Buprenorphine Prescribers to Those

Who Had Obtained by Prescription

(n=46)

Advised to attend AA/NA meetings:

29, or 63%

Advised to attend group or individual therapy:

28, or 61%

Suggested Duration and Reported

Duration of Buprenorphine MAT

In the first wave of subjects entered in the study (n =175)

the 34 subjects who had received prescription

buprenorphine MAT responded to this question as

follows: some do not recall having been told a time

frame for duration of treatment (n=16). There was one

report of a stated lifetime duration (i.e. - n=1). The 17

remaining subjects were told a range of 7 days or (n=1),

one month (n=2), 2 months (n=5), 3 months (n=2), 6

months (n=3), 9 months (n=1),12 months (n=2), 18

months (n= 2), and 24 months (n= 1).

In the second wave of enrollment, we asked subjects to

state how long they had stayed on buprenorphine. Seven

(7) subjects responded: “Does not remember” (n=1), 48

months (n=1), 24 months (n=1), 12 months (n= 2), 8

months (n=2).

Of Those Who Had Used

Buprenorphine (n = 146), Subjects

Who Report1 an Overdose When

Combining Buprenorphine with Other

Drugs or Alcohol

5, or 3.4%

1Note

well: whatever these experiences were for these few

subjects, they are the users who survived to report.

Diversion of Prescribed

Buprenorphine

In a third revision of the interview protocol,

subjects who reported ever having had received

buprenorphine by legal prescription (n = 11)

were asked if they had ever sold, traded, or

given away part of their prescription. Nine (n=

9), or 82%, answered “yes.” (One subject stated

bluntly that he only obtained prescribed

buprenorphine in order to sell it to others.)

SUMMARY POINTS

Is buprenorphine ever useful in addiction

treatment? Yes,

but only for

a) a very narrow range of patients

b) who are ONLY opiate-addicted

c) who do not show a significant family-history of

addiction

d) and only when used for a brief course of tapered

detoxification.

SUMMARY POINTS - Continued

Is buprenorphine an abused drug-of-reward? Yes.

Is buprenorphine often diverted? Yes.

Is buprenorphine addictive? Yes.

Is the withdrawal from buprenorphine easier to tolerate

than the withdrawal from methadone? No,

not if reports gathered in clinical interviews

are to be trusted.

Does a “ceiling-effect” protection against overdose-death

secondary to respiratory depression exist? Yes,

when ONLY buprenorphine is present. But safety

in this regard is not clearly established when

mixed with sedative-hypnotics. Nor is danger

in such cases established. Proceed with caution.

SUMMARY POINTS - Continued

Does the “ceiling effect” on respiration also

generalize to the prevention of euphoria? NO!

1) No research literature ever proves this assertion,

2) early research literature reports euphoria,

3) over 75-80% of the subjects from our addictionrecovery population report euphoria,

4) they report heightened euphoria by varying doses,

5) and they report mixing it with other substances to

enhance euphoria.

Are induction and maintenance dose choice well

established by research? No.

The Future for this Descriptive Study

The survey items which have yielded the pilot –

study information are now embedded in the

protocol used by the Center for Drug and Alcohol

Research, University of Kentucky, T.K. Logan, Ph.D.,

lead researcher. This center is tasked to collect data

continuously and regularly on participants at all

Healing Place locations in Kentucky (private, nonprofit) and at all Recovery Kentucky centers (a

division of the Commonwealth of Kentucky’s

Housing Authority). With this work, we hope to take

seriously the following famous statement:

"Facts do not cease to exist

because they are ignored."

-Aldous Huxley (1928)