Transport Layer Details - the Department of Information Technology

advertisement

Transport Layer

TCP and UDP

CT542

Content

•

•

•

•

Transport layer services provided to upper layers

Transport service protocols

Berkley Sockets

An Example of Socket Programming

–

•

Elements of transport protocols

–

•

Adressing, establishing and releasing a connection

Transport layer protocols

–

–

•

•

Internet file server

UDP

•

•

TCP

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

UDP segment header

Remote Procedure Call

Service model

TCP Protocol

The TCP Segment Header

TCP Connection Establishment

TCP Connection Release

TCP Connection Management Modeling

TCP Transmission Policy

TCP Congestion Control

TCP Timer Management

Wireless TCP and UDP

Additional Slides

Services provided to the upper layer

– Provides a seamless interface between the Application

layer and the Network layer

– The heart of the communications system

– Two types:

• Connection oriented transport service

• Connectionless transport service

– Key function is of isolating the upper layers from the

technology, design and imperfections of the subnet

(network layer)

– Allows applications to talk to each other without

knowing about

• The underlying network

• Physical links between nodes

Network, transport and application layers

TPDU

• Transport Packet Data Unit are sent from transport entity to

transport entity

• TPDUs are contained in packets (exchanged by network

layer)

• Packets are contained in frames (exchanged by the data link

layer)

Transport service primitives

• Transport layer can provide

– Connection oriented transport service, providing an error free

bit/byte stream; reliable service on top of unreliable network

– Connectionless unreliable transport (datagram) service

• Example of basic transport service primitives:

DISCONNECT

CONNECT

SEND/RECEIVE

primitives

a client

a server

connection

wants

can be

toused

talk

is notolonger

exchange

the server,

needed,

data

it executes

itafter

must

thebe

this

connection

released

primitive;

LISTEN ––inwhen

a– when

client

application,

the

server

executes

this inhas

the

been

order

transport

established;

to free blocking

up

entity

tables

either

caries

inthe

party

the

outserver

transport

this

could

primitive

do

entities;

(blocking)

itsending

can

RECEIVE

be asymmetric

a connection

for

packet

theend

other

primitive,

until

a(by

client

turns

upto wait(either

request

party

sends

to

a to

disconnection

dothe

SEND;

serverwhen

and

TPDU

waiting

the TPDU

to the

forremote

arrives,

a connection

transport

the receiver

accepted

entity;

is unblocked,

response),

upon arrival,

blocking

does

thethe the

required

connection

processing

is released)

andorsends

symmetric

back a (each

reply direction is closed separately)

caller until

the

connection

is established.

FSM modeling

• In a basic system you can be one of a finite number of

conditions (states)

–

–

–

–

–

listening - waiting for something to happen

connecting

connected

disconnected

whilst connected you can either be

• sending

• receiving

– In this way we have defined the problem to be a limited number of

states with a finite number of transitions between them

State diagram for a simple transport

manager

• Transitions in italics are caused by packet arrivals

• Solid lines show the client’s state sequence

• Dashed lines show the server’s sequence

Berkley sockets

• The first four primitives are executed in that order by the servers

• The client side:

– SOCKET must be called first to create a socket (first primitive)

• The socket doesn’t have to be bound since the address of the client doesn’t matter to the server

– CONNECT blocks the caller and actively establishes the connection with the server

– SEND/RECEIVE data over a full duplex connection

– CLOSE primitive has to be called to close the connection; connection release with

sockets is symmetric, so both sides have to call the CLOSE primitive

File server example:

Client code

File server example:

Server code

Transport protocol

• Transport protocols reassemble the data link protocols

– Both have to deal with error control, sequencing and flow control

• Significant differences between the two, given by:

– At data-link layer, two router communicate directly over a physical wire

– At transport layer, the physical channel is replaced by the subnet

• Explicit addressing of the destination is required for transport layer

• Need for connection establishment and disconnection (in the data-link

case the connection is always there)

• Packets get lost, duplicated or delayed in the subnet, the transport

layer has to deal with this

Addressing – fixed TSAP

• To whom should each message be sent??

– Have transport address to which processes can listen for connection requests

(or datagrams in connectionless transports)

– Host and process is identified Service Access Points (TSAP, NSAP)

• In Internet, TSAP is the port and NSAP is the IP

Addressing – dynamic TSAP

How a user process in

host 1 establishes a

connection with a

time-of-day server in

host 2.

•

Initial connection protocol

– Process server that acts as a proxy server for less-heavily used servers

– Listens on a set of ports at the same time for a number of incoming TCP connection requests

– Spawns the requested server, allowing it to inherit the existing connection with the user

•

Name server (directory server)

– Handles situations where the services exist independently of the process server (i.e. file server,

needs to run on special hardware and cannot just be created on the fly when someone wants to talk

to it)

– Listens to a well known TSAP

– Gets message specifying the service name and sends back the TSAP address for the given service

• Services need to register themselves with the name server, giving both its service name and its TSAP address

Establishing a connection

• When a communication link is made over a network (internet)

problems can arise:

– The network can lose, store and duplicate packets

• Use case scenario:

– User establishes a connection with a bank, instructs the bank to transfer large

amount of money, closes connection

– The network delivers a delayed set of packets, in same sequence, getting the

bank to perform another transfer

• Deal with duplicated packets

• There way handshake to establish a connection

Deal with duplicate packets (1)

• Use of throwaway TSAP addresses

– Not good, because the client-server paradigm will not work anymore

• Give each connection an unique identifier (chosen by the initiating party and

attached in each TPDU)

– After disconnection, each transport entity to update a used connections table (source

transport entity, connection identifier) pair

– Requires each transport entity to maintain history information

• Packet lifetime has to be restricted to a known one:

– Restricted subnet design

• Any method that prevents packets from looping

– Hop counter in each packet

• Having a hop counter incremented every time the packet is forwarded

– Time-stamping each packet

• Each packet caries the time it was created, with routers agreeing to discard any

packets older than a given time

• Routers have to have sync clocks (not an easy task)

– In practice, not only the packet has to be dead, but all the sequent acknowledges

to it are also dead

Deal with duplicate packets (2)

• Tomlinson (1975) proposed that each host will have

a binary counter that increments itself at uniform

intervals

– The number of bits in the counter has to exceed the

number of bits used in the sequence number

– The counter will run even if the host goes down

– The basic idea is to ensure that two identically numbered

TPDUs are never outstanding at the same time

– Each connection starts numbering its TPDUs with a

difference sequence number; the sequence space should

be so large that by the time sequence numbers will wrap

around, old TPDUs with the same sequence numbers are

long gone

Connection Establishment

– Control TPDUs may also be delayed; Consider the

following situation:

• Host 1 sends CONNECTION REQ (initial seq. no, destination

port no.) to a remote peer host 2

• Host 2 acknowledges this req. by sending CONNECTION

ACCEPTED TPDU back

• If first request is lost, but a delayed duplicate CONNECTION

REQ suddenly shows up at host 2, the connection will be

established incorrectly; 3 way handshake solves this;

– 3-way handshake

• Each packet is responded to in sequence

• Duplicates must be rejected

Three way handshake

• Three protocol scenarios for establishing a connection using a

three-way handshake.

– CR and ACK denote CONNECTION REQUEST and CONNECTION

ACCEPTED, respectively.

(a) Normal operation.

(b) Old duplicate CONNECTION REQUEST appearing out of nowhere.

(c) Duplicate CONNECTION REQUEST and duplicate ACK.

Asymmetric connection release

• Asymmetric release

– Is abrupt and may result in loss of data

Symmetric connection release (1)

Four protocol scenarios for releasing a connection.

(a) Normal case of a three-way handshake

(b) final ACK lost – situation saved by the timer

Symmetric connection release (2)

(c) Response lost

(d) Response lost and subsequent DRs lost

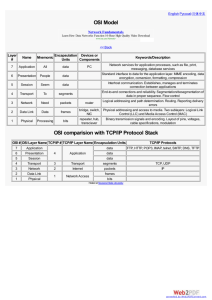

TCP/IP transport layer

• Two end-end protocols

– TCP - Transmission Control Protocol

• connection oriented (either real or virtual)

• fragments a message for sending

• combines the message on receipt

– UDP - User Datagram Protocol

• connection less - unreliable

• flow control etc provided by application

• client server application

The big picture

IPv6 Applications

AF_INET6

sockaddr_in6{}

IPv4 Applications

AF_INET

sockaddr_in{}

m-routed

ping

traceroute

app

app

app

app

traceroute

ping

API

TCP

UDP

transport

ICMP

IGMP

network

IPv4

32 bit

address

128 bit

address

IPv6

ARP/

RARP

data-link

• Internet has two main protocols at the transport layer

– Connectionless protocol: UDP (User Datagram Protocol)

– Connection oriented protocol: TCP (Transport Control Protocol)

ICMP

v6

User Datagram Protocol

• Simple transport layer protocol described in RFC 768, in

essence just a IP datagram with a short header

• Provides a way to send encapsulated raw IP datagrams

without having to establish a connection

– The application writes a datagram to a UDP socket, which is

encapsulated as either IPv4 or IPv6 datagram that is sent to the

destination; there is no guarantee that UDP datagram ever reaches

its final destination

– Many client-server application that have one request – one

response use UDP

• Each UDP datagram has a length; if a UDP datagram

reaches its final destination correctly, then the length of the

datagram is passed onto the receiving application

• UDP provides a connectionless service as there is no need

for a long term relation-ship between a client and the server

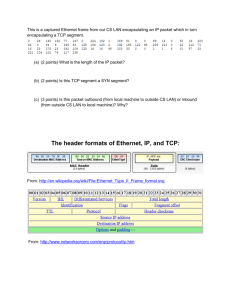

UDP header

• UDP segment consists of 8 bytes header followed by the data

• The source port and destination port identify the end points within the

source and destination machines; without the port fields, the transport

would not know what to do with the packet; with them, it delivers the

packets correctly to the application attached to the destination port

• The UDP length field includes the 8 byte header and the data

• The UDP checksum includes the 1 complement sum of the UDP data

and header. It is optional, if not computed it should be stored as all

bits “0”.

UDP

• Does not:

– Flow control

– Error control

– Retransmission upon receipt of a bad segment

• Provides an interface to the IP protocol, with the added feature of

demultiplexing multiple processes using the ports

• One area where UDP is useful is client server situations where the

client sends a short request to the server and expects a short replay

– If the request or reply is lost, the client can timeout and try again

• DNS (Domain Name System) is an application that uses UDP

– shortly, the DNS is used to lookup the IP address of some host name; DNS

sends and UDP packet containing the host name to a DNS server, the server

replies with an UDP packet containing the host IP address. No setup is needed in

advance and no release of a connection is required. Just two messages go over

the network)

• Widely used in client server RPC

• Widely used in real time multimedia applications

Remote Procedure Call (1)

• Sending a message to a server and getting a reply back is like making a function call

in programming languages

• i.e. gethostbyname(char *host_name)

– Works by sending a UDP packet to a DNS server and waiting for the reply, timing out

and trying again if an answer is not coming quickly enough

– All the networking details are hidden from the programmer

• Birrell and Nelson (1984) proposed the RPC mechanism

– Allows programs to call procedures located on remote hosts, and makes the remote

procedure call look as much alike a local procedure call

– When a process on machine 1 calls a procedure on machine 2, the calling process on

machine 1 is suspended and execution of the called procedure takes place on 2

– Information can be transported from caller to the callee in the parameters and can come

back in the procedure result

– No message parsing is visible to the programmer

• Stubs

– The client program must be bound with a small library procedure, called the client stub,

that represents the server procedure in the client’s address space

– Similarly, the server is bound with a procedure called the server stub

– Those procedures hide the fact that the procedure call from the client to the server is not

local

Remote Procedure Call (2)

Step 5:

1: the

2:

3:

4:

Client

client

kernel

server

calling

stub

stub

is sending

on

the

the

isispacking

receiving

calling

client

thestub.

the

message

themachine

server

parameters

This from

isprocedure

is

a local

passing

the

into

client

procedure

awith

the

message

machine

message

the call,

unmarchaled

and

towith

from

makes

the the

server

thea

parameters

system

machine,

transport

parameters.

call

stack

over

pushed

to send

atotransport

the

into

theserver

message;

theand

stack

stub.

network

packing

in the protocol.

normal

the parameters

way

is called marshaling,

and it is a very wide use technique.

The reply traces the same path in the other direction

Problems with RPC

• Use of pointer parameters

– Using pointers is impossible, because the client and the

server are in different address spaces

– Can be tricked by replacing the call by reference

mechanism with a copy-restore one

• Problems with custom defined type of data

• Problems using global variables as means of

communication between the calling and called

procedures

– If the called procedure is moved on a remote machine,

because the variables are not longer shared

Transmission Control Protocol

• Provides a reliable end to end byte stream over unreliable

internetwork (different parts may have different topologies,

bandwidths, delays, packet sizes, etc…)

• Defined in RFC793, with some clarifications and bug fixes in

RFC1122 and extensions in RFC1323

• Each machine supporting TCP has a TCP transport entity (user

process or part of the kernel) that manages TCP streams and interfaces

to the IP layer

– Accepts user data streams from local processes, breaks them into pieces (not

larger than 64KB) and sends each piece as a separate IP datagram

– At the receiving end, the IP datagrams that contains TCP packets, are delivered

to the TCP transport entity, which reconstructs the original byte stream

– The IP layer gives no guarantee that the datagrams will be delivered properly, so

it is up to TCP to time out and retransmit them as the need arises.

– Datagrams that arrive, may be in the wrong order; it is up to TCP to reassemble

them into messages in the proper sequence

TCP Service Model (1)

• Provides connections between clients and servers, both the

client and the server create end points, called sockets

– Each socket has a number (address) consisting of the IP address of

the host and a 16 bits number, local to that host, called port (TCP

name for TSAP)

– To obtain a TCP service, a connection has to be explicitly

established between the two end points

– A socket may be used for multiple connections at the same time

– Two or more connections can terminate in the same socket;

connections are identified by socket identifiers at both ends

(socket1, socket2)

• Provides reliability

– When TCP sends data to the other end it requires

acknowledgement in return; if ACK is not received, the TCP entity

retransmits automatically the data and waits a longer amount of

time

TCP Service Model (2)

• TCP contains algorithms to estimate round-trip time between a client

and a server to know dynamically how long to wait for an

acknowledgement

• TCP provides flow control – it tells exactly to its peer how many bytes

of data is willing to accept from its peer.

• Port numbers bellow 1024 are called well known ports and are

reserved for standard services

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Port 21 used by FTP (File Transfer Protocol)

Port 23 used by Telnet (Remote Login)

Port 25 used by SMTP (E-mail)

Port 69 used by TFTP (Trivial File Transfer Protocol)

Port 79 used by Finger (lookup for a user information)

Port 80 used by HTTP (World Wide Web)

Port 110 used by POP3 (remote e-mail access)

Port 119 used by NNTP (Usenet news)

TCP Service Model (3)

• All TCP connections are full duplex and point to point (it

doesn’t support multicasting or broadcasting)

• A TCP connection is a byte stream not a message stream

(message boundaries are not preserved)

– i.e. if a process is doing four writes of 512 bytes to a TCP stream,

data may be delivered at the other end as four 512 bytes reads, two

1024 bytes reads or one 2048 read

(a) Four 512-byte segments sent as separate IP datagrams.

(b) The 2048 bytes of data delivered to the application in a single READ

CALL.

TCP Service Model (4)

• When an application sends data to TCP, TCP entity may

send it immediately or buffer it (in order to collect a larger

amount of data to send at once)

– Sometimes the application really wants the data to be sent

immediately (i.e. after a command line has been finished); to force

the data out, applications can use the PUSH flag (which tells TCP

not to delay transmission)

• Urgent data – is a way of sending some urgent data from

one application to another over TCP

– i.e. when an interactive user hits DEL or CTRL-C key to break-off

the remote computation; the sending app puts some control info in

the TCP stream along with the URGENT flag; this causes the TCP

to stop accumulating data and send everything it has for that

connection immediately; when the urgent data is received at the

destination, the receiving application is interrupted (by sending a

break signal in Unix), so it can read the data stream to find the

urgent data

TCP Protocol Overview (1)

• Each byte on a TCP connection has its own 32 bit sequence

number, used for various purposes (re-arrangement of out of

sequence segments; identification of duplicate segments,

etc…)

• Sending and receiving TCP entities exchange data in the

form of segments. A segment consists of a fixed 20 byte

fixed header (plus an optional part) followed by zero or

more data bytes

• The TCP software decide how big segments should be; it

can accumulate data from several writes to one segment or

split data from one write over multiple segments.

– Two limits restrict the segment size:

• Each segment including the TCP header must fit the 65535 byte IP payload

• Each network has an maximum transfer unit (MTU) and each segment must

fit in the MTU (in practice the MTU is a few thousand bytes and therefore

sets the upper bound on the segment size)

TCP protocol Overview (2)

• The basic protocol is the sliding window protocol

– When a sender transmits a segment, it also starts a timer

– When the segment arrives at the destination, the receiving TCP

sends back a segment (with data, if any data is to be carried)

bearing an acknowledgement number equal to the next sequence

number it expects to receive;

– If sender’s timer goes off, before an acknowledgement has been

received, the segment is sent again

• Problems with the TCP protocol

– Segments can be fragmented on the way; parts of the segment can

arrive, but some could get lost

– Segments can be delayed and duplicates can arrive at the receiving

end

– Segments may hit a congested or broken network along its path

TCP segment header

Options

Source

Sequence

TCP

URG

ACK

PSH

RST

SYN

FIN

Flow

Checksum

flag

flag

header

flag

flag

control

flag

and

field

is

is

indicates

is

Number

isis

used

destination

used

set

set

length

provided

in

was

to

to

TCP

to

to1designated

1isrelease

pushed

restart

establish

tells

to

ifassociated

isurgent

indicate

for

done

ports

how

aextreme

connections;

data,

connection

connections;

using

identify

many

pointer

tothat

with

provide

so variable

reliability.

the

32

the

every

is

the

bit

receiver

acknowledgement

that

in

itextra

local

words

specifies

use;

the

byte

size

has

connection

It

facilities

endpoints

the

is

become

checksums

sliding

that

are

requested

urgent

that

contained

is sent.

not

window;

the

confused

for

pointer

requests

number

covered

sender

the

to

Itthe

is

deliver

in

header,

connection;

used

the

is

the

due

have

is

has

used

by

Window

valid;

TCP

for

to

the

no

the

the

SYN

to

aamore

received

header;

regular

host

data

if

indicate

each

set

=

size

1to

host

number

athis

0,

crash

data

field

and

header;

byte

then

ACK

is

the

may

to

tells

or

required

offset

the

transmit;

the

conceptual

the

of

any

decide

how

=different

application

packet

most

0other

from

tomany

because

indicate

Both

for

important

doesn’t

the

reasons;

pseudo-header

purposes:

itself

bytes

current

SYN

upon

the

that

how

contain

may

it

one

Options

and

arrival,

the

is

sequence

ittois

also

be

FYN

ispiggyback

allocate

the

an

shown

used

sent

without

field

used

acknowledgement,

one

segments

starting

number

tois

to

on

that

the

re-arrange

of

reject

acknowledgement

buffering

the

its

allows

variable

at

have

own

next

the

which

an sequence

invalid

the

each

slide;

ports

byte

itlength;

to

so

data

urgent

host

acknowledged;

form

starting

the

when

segment

attechnically

number

field

appropriate

to

data

the

a performing

specify

full

atreceiving

isis1024;

or

buffer

not

to

and

refuse

be

the

it

in

afield

thus

ause;

has

the

port

end,

anis

number

before

indicates

found;

ignored

been

attempt

the

guaranteed

window

computation,

maximum

connection

received

passing

this

to

plus

(the

size

the

open

TCP

facilitates

toAcknowledgement

its

start

field

the

be

itresponse

payload

host

ato

processed

data

connection

of

with

the

data

IP

interrupt

field

application;

value

form

is

does

within

willing

is

ina0padded

bear

correct

48

messages

isnumber

the

legal

bits

to

an

itsegment,

accept;

with

order

is

acknowledgment

unique

and

used

field

without

an

means

all

to

TSAP

additional

is

measured

Internet

detect

ignored)

getting

that duplicate

bytes

so

in

hosts

zero

the

it32has

TCP

up

byte

bits

areto

data

SYN

itself

required

words.

if itsand

=involved

length

1 and

to is an

in

Acknowledgement

carrying

ACK

(Acknowledgement

odd

accept

number;

=at1;such

leastthe

message

536

checksum

number

+20

number

types

TCPis

fields

-1)

segments

simply

have

specifies

been

the sum

received,

theinnext

1’s byte

complement

and no

expected

more accepted

TCP pseudoheader

• The pseudoheader contains the 32 bits IP addresses of the

source and the destination machines, the protocol number (6

for TCP) and the byte count for the TCP segment (including

the header)

• Including this pseudoheader in the TCP checksum

calculation helps detect miss-delivered packets, but doing so

violates the protocol hierarchy (since IP addresses belong to

the network layer, not to the TCP layer)

TCP extra options

• For lines with high bandwidth and high delay, the 64KB widow size is

often a problem

– i.e. on a T3 line (44.736 Mb/s) it takes only about 12ms to output a full 64KB

window. If the round trip propagation delay is 50 ms (typical for a

transcontinental fiber), then the sender will be idle ¾ of the time, waiting for

acknowledgements

– In RFC 1323 a window scale option was proposed, allowing the sender and

receiver to negotiate a window scale factor. This number allows both sides to

shift the window size up to 14 bits to the left, thus allowing for window size up

to 230 bytes; most TCP implementations support this option

• The use of “selective repeat” instead of “go and back n” protocol

described in RFC 1106

– If the receiver gets a bad segment and then a large number of good ones, the

normal TCP protocol eventually time out and retransmit all the unacknowledged

segments, including the ones that were received correctly

– RFC 1106 introduces NACs to allow the receiver to ask for a specific segment

(or segments). After it gets those, it can acknowledge all the buffered data, thus

reducing the amount of data retransmitted.

TCP connection establishment

It is use the three-way handshake protocol

a) Normal case

b) Call collision case, when two hosts are trying to establish a connection

between same two sockets

– The result is that just one connection will be established, not two, because the

connections are identified by their endpoints.

TCP connection establishment …

client

socket

connect (blocks)

2

SYN X

(active

connection)

connect returns

4

X+1

SYN Y, AC K

SEQ = X+1

, ACK=Y+1

server

socket, bind, listen

1

(pasive connection)

accept (bocks)

3

accept returns

read (blocks)

The

[2]

initial

client,

sequence

after

the

number

creation

onof

a connection

a new

socket,

is not

issues

(to

anavoid

active

confusion

open

by calling

whenmust

a

[1]the

[3]

[4]the

the

the

client

server

server

must

must

must

acknowledge

be prepared

acknowledge

to

the

the

accept

server’s

client’s

an0 SYN

incoming

SYN

and

connection;

the server

connect.

host

This

Aown

clock

the

based

client

scheme

TCP tois socket,

send

used,

SYN

a segment

clock

(which

every

stands

4 us.

this crashes).

also

issend

normally

itscauses

done

SYN

bycontaining

calling

theawith

initial

bind

sequence

andtick

listen

number

and

it For

isfor

for the

synchronize)

additional

safety,

to tell

when

the server

a host crashes,

the client’s

it may

initial

notsequence

reboot for

number

the maximum

for the data

packet

thatlife

called

data

Note

that

that

passive

the

SYN

server

open

consumes

will

send

one

on

byte

the

of

connection.

sequence

space

The

server

so

it

can

sends

be

SYN

the client

time

(120s)

will

to send

makeon

sure

thethat

connection;

no packets

normally

from previous

there is connections

no data sent are

withstill

SYN:

roaming

it

and

acknowledged

thetheACK

ofunambiguously

the

client’s

single segment

just contains

around

Internet,

an IP

header,

somewhere.

a TCP SYN

headerin

anda possible

TCP options

TCP connection termination

• The connection is full duplex, each simple connection is released

independently

• To release a connection, either party can send a TCP segment with

FIN bit set, which means that there is no more data to transmit

• When FIN is acknowledged, that direction is shut down for new data;

however, data may continue to flow indefinitely in the other direction

• When both directions have been shutdown, the connection is released

• Normally, four TCP segments are used to shutdown the connection

(one FIN and one ACK for each direction)

• To avoid complications when segments are lost, timers are used; if the

ACK for a FIN packet is not arriving in two packet lifetimes, the

sender of the FIN releases the connection; the other side will

eventually realize that nobody seem to listen to it anymore and times

out as well

TCP connection termination

client

server

(pasive close)

(active close)

close

1

FIN M

2

read returns 0

ACK M+1

FIN N

4

3

close

ACK=N+1

[2]

other

end

receives

theapplication

FIN

andfirst,

performs

a passive

close.

Theend

received

SYN

[3]

[4]

[1]the

sometime

the

one

TCP

application

onlatter,

the system

calls

the

close

that

receives

that

and the

received

we

final

say that

FIN

thethis

end-of-file

(the

endperforms

that

will

didis

acknowledged

by theThis

TCP;

the cause

receipt

of

the

FIN

issend

also

passed

the application

close

the

the active

active

the socket;

close)

close.

acknowledges

this

will

end’s

TCPthe

its

sends

TCP

FIN

ato

FIN

segment,

a FINonto

packet

which

means it

as an end-of-file; upon the receipt of FIN, the application will not receive anymore

is finished sending data

any data on the socket

TCP state transition diagram

• The heavy solid line –

client

• The heavy dashed line

– server

• The light lines unusual events

• Each transition is

labeled by Event causing

it/Action

TCP transmission policy

• Window management in TCP, starting with the client

having a 4096 bytes buffer

TCP transmission policy

• When window size is 0 the sender can’t send segments with

two exceptions

– Urgent data may be sent (i.e. to allow the user to kill the process

running on the remote machine)

– The sender may send 1 byte segment to make the receiver reannounce the next byte expected and window size

• Senders are not required to send data as soon as they get it

from the application layer;

– i.e. when the first 2KB of data came in from the application, TCP

may have decided to buffer it until the next 2KB of data would

have arrived, and send at once a 4KB segment (knowing that the

receiver can accept 4KB buffer)

– This leaves space for improvements

• Receivers are not required to send acknowledgements as

soon as possible

TCP performance issues (1)

• Consider a telnet session to an interactive editor that reacts

to every keystroke, we will have the worst case scenario:

– when a character arrives at the sending TCP entity, TCP creates a

21 bytes segment, which is given to IP to be sent as a 41 bytes

datagram;

– at the receiving side, TCP immediately sends a 40 bytes

acknowledgement (20 bytes TCP segment headers and 20 bytes IP

headers)

– Latter, at the receiving side, when the editor (application) has read

the character, TCP sends a window update, moving the window 1

byte to the right; this packet is also 40 bytes

– Finally, when the editor has interpreted the character, it will echo it

as a 41 byte character

• We will have 162 bytes of bandwidth are used and four

segments are sent for each character typed.

TCP optimizations – delayed ACK

• One solution that many TCP implementation use to

optimize this situation is to delay acknowledgements

and window updates for 500ms

– The idea is the hope to acquire some data that will be

bundled in the ACK or window update segment

• i.e. in the editor case, assuming that the editor sends the echo

within 500 ms from the character read, the window update and

the actual byte of data will be sent back as a 41 bytes packet

– This solution deals with the problem at the receiver end,

it doesn’t solve the inefficiency at the sending end

TCP optimizations – Nagle’s algorithm

• Operation:

– When data come into the sender TCP one byte at a time, just send the first byte

as a single TCP segment and buffer all the subsequent ones until the first byte is

acknowledged

– Then send all the buffered characters in one TCP segment and start buffering

again until they are all acknowledged

– The algorithm additionally allows a new segment to be sent if enough data has

accumulated to fill half the window or a new maximum segment

• If the user is typing quickly and the network is slow, then a substantial

number of characters may go in each segment, greatly reducing the

usage of the bandwidth

• Nagle’s algorithm is widely used in TCP implementations; there are

some times when it is better to disable it:

– i.e. when an X-Window is run over internet, mouse movements have to be sent

to remote computer; gathering them and send them in bursts, make the cursor

move erratically at the other end.

TCP performance issues (2)

• Silly window syndrome (Clark, 1982)

– Data is passed to the sending TCP entity in large blocks

– Data is read at the receiving side in small chucks (1 byte)

TCP optimizations – Clark’s solution

• Clark’s solution:

– Prevent the receiver from sending a window update for 1 byte

– Instead have the receiver to advertise a decent amount of space

available; specifically, the receiver should not send a window

update unless it has space to handle the maximum segment size

(that has been advertised when the connection was established) or

its receiving buffer its half empty, which ever is smaller

– Furthermore, the sender can help by not sending small segments;

instead it should wait until it has accumulated enough space in the

window to send a full segment or at least one containing half of the

receiver’s buffer size (which can be estimated from the pattern of

window updates it has received in the past)

Nagle’s algorithm vs. Clark’s solution

• Clark’s solution to the silly window syndrome and Nagle’s

algorithm are complementary

– Nagle was trying to solve the problem caused by the sending

application deliver data to TCP one byte at a time

– Clark was trying to solve the problem caused by the receiving

application reading data from TCP one byte at a time

– Both solutions are valid and can work together. The goal is for the

sender not to send small segments and the receiver not to ask for

them

• The receiving TCP can also improve performance by

blocking a READ request from the application until it has a

large chunk of data to provide:

– However, this can increase the response time.

– But, for non-interactive applications (e.g. file transfer) efficiency

may outweigh the response time to individual requests.

TCP congestion control

• TCP deals with congestion by dynamically

manipulating the window size

• First step in managing the congestion is to detect it

– A timeout caused by a lost packet can be caused by

• Noise on the transmission line (not really an issue for modern

infrastructure)

• Packet discard at a congested router

– Most transmission timeouts are due congestion

• All the Internet TCP algorithms assume that

timeouts are due to congestion and monitor timeouts

to detect congestion

TCP congestion control

• Two types of problems can occur:

– Network capacity

– Receiver capacity

• When the load offered to a network is more than it can handle, congestion builds up

– (a) A fast network feeding a low capacity receiver.

– (b) A slow network feeding a high-capacity receiver.

TCP congestion control

• TCP deals with network capacity congestion and receiver

capacity congestion separately; the sender maintains two

windows

– The window that the receiver has guaranteed

– The congestion window

• Both of the windows reflect the number of bytes that the

sender may transmit; the number that can be transmitted is

the minimum of the two windows

– If the receiver says “send 8K” but the sender knows that more than

4K will congest the network, it sends 4K

– On the other hand, if the receiver says “send 8K” and the sender

knows that the network can handle 32K, then it sends the full 8K

– Therefore the effective window is the minimum between what the

sender thinks is all right and the receiver thinks is all right

Slow start algorithm (Jacobson, 1988)

• When a connection is established, the sender initializes the congestion

window to the size of a the maximum segment in use; it then sends a

maximum segment

– If the segment is acknowledged in time, the sender doubles the size of the

congestion window (making it twice the size of a segment) and sends two

segments, that have to be acknowledged separately

– As each of those segments is acknowledged in time, the size of the congestion

window is increased by one maximum segment size (in effect, each burst

successfully acknowledged doubles the congestion window)

• The congestion window keeps growing until either a timeout occurs or

the receiver’s window is reached

• The idea is that if bursts of size, say 1024, 2048, 4096 bytes work

fine, but burst of 8192 bytes timeouts, congestion window remains at

4096 to avoid congestion; as long as the congestion window remains

at 4096, no larger bursts than that will be sent, no matter how much

space the receiver grants

Slow start algorithm (Jacobson, 1988)

• Max segment size is 1024 bytes

• Initially the threshold was 64KB,

but a timeout occurred and the

threshold is set to 32KB and the

congestion window to 1024 at

transmission time 0

• The internet congestion algorithm uses a third parameter, the threshold, initially

64K, in addition to the receiver and congestion windows.

– When a timeout occurs, the threshold is set to half of the current congestion window, and

the congestion window is reset to one maximum segment size.

• Each burst successfully acknowledged doubles the congestion window.

– It grows exponentially until the threshold value is reached.

– It then grows linearly until the receivers window value is reached.

TCP timer management

• TCP uses multiple timers to do its work

– The most important is the retransmission timer

• When a segment is sent, a retransmission timer is started

• If the segment is acknowledged before this timer expires, the

timer is stopped

• If the timer goes off before the segment is acknowledged, then

the segment gets retransmitted (and the timer restarted)

• The big question is how long this timer interval should be?

– Keepalive timer is designed to check for connection

integrity

• When goes off (because a long time of inactivity), causing one

side to check if the other side is still there

TCP timer management

• TCP uses multiple timers to do its work

– Persistence timer is designed to prevent deadlock

• Receiver sends a packet with window size 0

• Latter, it sends another packet with larger window size, letting

the sender know that it can send data, but this segment gets lost

• Both the receiver and transmitter are waiting for the other

• Solution: persistence timer on the sender end, that goes off and

produces a probe packet to go to the receiver and make it to

advertise again its window

– TIMED WAIT state timer used when a connection is

closed; it runs for twice the maximum packet lifetime to

make sure that when a connection is closed, all packets

belonging to this connection have died off.

Wireless TCP

• The principal problem is the congestion control algorithm,

because most of the TCP implementations assume that

timeouts are caused by congestion and not by lost packets

• Wireless networks are highly unreliable

– The best approach with lost packets is to send them ASAP,

slowing down (Jacobson slow start) only makes things worst

• When a packet is lost

– On wired networks, the sender should slow down

– On wireless networks, the sender should try harder

• If the type of network is not known, it is difficult to make

the correct decision

Wireless TCP

• The path from sender to receiver is inhomogeneous

– Making the decision on a timeout is very difficult

• Solution proposed by Bakne and Badrinath (1995) is to split the TCP connection

into two separate TCP connections (indirect TCP)

– First connection goes from sender to the base station

– Second connection from base station to the mobile receiver

– Base-station simply copies packets between the connections in both directions

• Both connections are homogenous, timeouts on first connection can slowdown the

sender while on the second connection makes the sender (base-station) try harder

Wireless TCP - Balakrishnan et al (1995)

• Doesn’t break the semantics of the TCP, works by making small

modifications of the code at the base station end

– Addition of an agent that would cache all the TCP segments going out to the

TCP mobile host and ACK coming back from it;

– When the agent sees a TCP segment going out but no ACK coming back, it will

issue a retransmission without letting the sender know what is going on

– It also generates retransmission when it sees duplicate ACK coming from the

mobile host (it means the mobile host missed something)

– Duplicate ACK are discarded by the agent (to avoid the source interpret it as

congestion)

• One problem is that if the wireless net is very lossy, the sender may

timeout and invoke the congestion control algorithm; with indirect

TCP the congestion algorithm wouldn’t be started unless there is

really congestion in the wired part

• There is a fix for to the problem of lost segments originating at the

mobile host

– When the base-station notices a gap in the inbound sequence numbers, it

generates a request for a selective repeat of the missing bytes using a TCP

option

References

• Andrew S. Tanenbaum – Computer Networks,

ISBN: 0-13066102-3

• Behrouz A. Forouzan – Data Communications

and Networking, ISBN: 0-07-118160-1

Additional Slides

Quality of service

RTTP, RTCP and Transactional TCP

Supplement - Quality of service (1)

• Connection establishment

– Delay – time between the request has been issued and the confirmation being

received; the shorter the delay, the better the service

– failures

• Throughput – the number of bytes of user data transferred per second; it is

measured separately for each direction

• Transit delay – the time between a message being sent by the transport user

the source machine and its being received by the transport user on the

destination machine

• Residual error ratio – the number of lost messages as a fraction of the total

sent; it theory it should be 0

• Protection – provides a way for the user to make the transport layer provide

protection against unauthorized third parties

• Priority – a way for the transport user to indicate that some of its

connections are more important then other ones (in case of congestion)

• Robustness – probability of the transport layer spontaneously terminating a

link

Supplement - Quality of service (2)

• Achieving a good quality of service requires negotiation

– Option negotiation – QoS parameters are specified by the transport

user when a connection is requested; desired and minimum values

can be given

• May immediately realize that the requested value is not achievable,

returning to the caller an error, without contacting the destination

• May request a lower value from the destination (i.e. it knows it can’t achieve

600Mb/s but it can achieve a lower, still acceptable rate, 150Mb/s); it

contacts the destination with the desirable and minimum value; the

destination can make a counteroffer …etc.

– Good quality lines cost more

• Maintain the negotiated parameter over the life of the

connection

Real Time Transport Protocol

• Described in RFC 1889 and used in multimedia applications (internet

radio, internet telephony, music on demand, video on demand, video

conferencing, etc..)

• The position of the RTP in the protocol stack is somewhat strange: it

has been decided to be in user space and work normally over UDP

• Working model:

– The multimedia application generates multiple streams (audio, video, text, etc)

that are fed into the RTP library;

– The library multiplexes the streams and encodes them in RTP packets which are

fed to a UDP socket

– The UDP entity is generating UDP packets that are embedded into IP packets;

IP packets are embedded into Ethernet frames and sent over the network (if the

network is ETH)

• It is difficult to say which layer the RTP is in (transport or application)

• Basic function of RTP is to multiplex several real time data streams

into a single stream of UDP packets; the UDP stream can be sent to

single destinations (unicast) or to multiple destinations (multicast)

Real Time Transport Protocol

(a) The position of RTP in the protocol stack.

(b) Packet nesting.

Real Time Transport Protocol

• Each packet has a number, one higher than its

predecessor

– Used by the destination to determine missing packets

– If packet is missing, best action is to try and interpolate it

• No flow control, no retransmission, no error control

• RTP payload may contain multiple samples coded

any way the application wants

• Allows for time-stamping (time relative to the start

of the stream, so only differences are significant)

– This is used to play synchronously certain streams

RTP header

P bit

indicates

the

packet

has

padded

tothe

apresent

multiple

of 4first

Contributing

The

Sequence

The

Synchronization

X

CC

Payload

timestamp

bitfield

number

tellstype

source

tells

that

issource

produced

field

how

isthat

anidentifier,

just

extension

tells

many

identifier

a counter

by

which

contributing

if

the

header

any,

tells

stream’s

that

encoding

isbeen

which

increments

is

used

present;

sources

source

algorithm

when

stream

are

the

to

on

mixers

note

each

format

has

packet

when

are

been

RTP

and

present

belongs

packet

the

used

in

bytes;

last

padding

byte

tells

how

many

bytes

were

added

meaning

The

(MP3,

sent;

sample

to;

the

itstudio;

M

is

itthe

PCM,

is

bit

the

inof

used

the

isin

method

the

an

etc);

that

packet

toextension

application

detect

case,

since

used

was

the

lost

every

tomade;

header

multiplex

mixer

specific

packets

packet

this

are

is the

marker

field

not

and

carries

synchronization

defined;

demultiplex

can

bit;

this

help

it field,

the

can

reduce

only

be

multiple

the

source

used

jitter

thing

encoding

todata

and

by

that

mark

the

is

can

defined

the

change

decoupling

streams

startduring

is

over

being

ofthe

athe

video

one

first

mixed

transmission

playback

single

word

frame

arestream

of

listed

from

the the

extension

here.

of UDP

packetpackets.

that

arrival

gives

time

the length; this is an

escape mechanism for unforeseen requirements

Real Time Transport Control Protocol

• It handles feedback, synchronization for the RTP but

is not actually transporting any data

• Feedback on delay, jitter, bandwidth, congestion and

any other networking parameters

• Handles inter-stream synchronization whenever

different streams use different clocks with different

granularities

• Provides a way of naming different sources (i.e. in

ASCII text); this information can be displayed at the

receiver end to display who is talking at the moment

Transactional TCP

• UDP is attractive as transport for RPC only if the request and the

reply fit into a single packets

• If the reply is large, using TCP as transport may be the solution, still

some efficiency related problems

– To do RPC over TCP, nine packets are required (best case scenario)

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Client sends SYN packet to establish a connection

Server sends ACK + its SYN

The client completes the three way handshake with an ACK

The client sends an actual request

The client sends a FIN packet to indicate it is done sending

The server acknowledges the request and the FIN packet

The server sends back the reply to the client

The server sends a FIN packet to indicate it is done

The client acknowledges the server's FIN

• Performance improvement to TCP is required, this is done in

Transactional TCP, described in RFC 1379 and 1644

Transactional TCP

(a) RPC using normal TPC (b) RPC using T/TCP.

• The idea is to modify the standard connection setup

to allow data transport