Edexcel climate update

advertisement

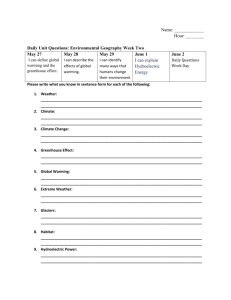

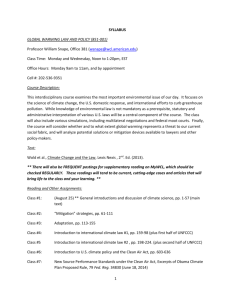

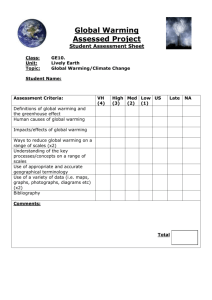

CLIMATE CHANGE UPDATE Edexcel GCE Geography AS Unit 1 PowerPoint presentation with notes January 2011 Climate change update 2010 PowerPoint outline • Climate change and its causes • The Impacts of global warming • Coping with climate change Climate change: the long-term evidence Temperature rise The longterm data show natural variability but a fairly steady longterm trend. In the last 100 years there is a strong upwards movement away from the established trend. Climate change: more evidence for change Extreme events • The 2010 floods in Pakistan left millions homeless and at least one-fifth of the country under water. • In Russia, the summer 2010 drought led to wildfires. • Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) reached a high of 52°C in 2010. • The UK had its heaviest snowfalls and coldest weather for decades in December 2010. • Extreme events of any single year cannot be taken as definite proof of climate change. • But most scientists say events in Pakistan and Russia in 2010 can be seen as consistent with climate change predictions. Climate change: natural or human causes? (1) Evaluating the evidence Temperature rises and CO2 levels are always linked in the historical record. CO2 levels are now their highest for 800,000 years. This coincides with unprecedented temperature rises. Despite recent media controversy over aspects of how climate change data have been handled by some scientists, humans are almost certainly to blame for recent global warming. Climate change: natural or human causes? (2) Other influences at work ? El Nino and La Nina events naturally last for a few years and cause weather changes in many places. •The North Atlantic Oscillation is another climatic phenomenon that may be linked with the recent cold winter in the UK in 2010. •Sunspot activity can lead to temperature change. •But none of these explain recent global warming. Climate change: unprecedented warming Warming trends Sea surface temperatures record a rise (this might lead to more hurricane activity). Temperatures over land are rising too. (These trend lines relate to the recorded average for 1960-1990.) Arctic impacts of global warming (1) Melting ice The Artic is heating twice as fast as the rest of the world and even faster than models predicted. The region may yet warm by as much as 16°C ! Some years can bring a minor recovery of ice; but the longterm trend is greater melting. Impacts of global warming: sea-level rise The causes • Sea-levels around the UK have risen by 10 cm since 1900. Globally, sea-levels is rising – the result of a warming climate in two important ways: • 1. Thermal expansion – as water warms it expands, like liquid in a thermometer. • 2. Melting land-based ice (but not sea ice – this has no effect). Large amounts of water are locked on land in glaciers and permafrost. Meltwater from this pours into oceans, raising levels. • Global sea level rise of this kind is called a eustatic change. • Local changes – such as land subsidence in delta regions – can make the problem even worse. Impacts of global warming: IPCC scenarios (1) Temperature predictions A wide range of predictions exist as a result of IPCC 2007 and more recent NOAA 2010 analysis. It is broadly accepted by most scientists that a rise of 1.5 – 4.0 °C is now inevitable. Impacts of global warming: IPCC scenarios (2) Changing precipitation Warmer air holds more moisture - so precipitation may rise in today’s cooler places. Areas that are already arid may suffer even lower rainfall. But there is uncertainty about how rainfall patterns will change overall. Impacts of global warming: the tipping points Albedo & methane • ‘Tipping point’ effects are those that result in positive feedback and an acceleration of changes like global warming. • Loss of snow and ice cover could cause positive feedback (as albedo values change and less and less sunlight is reflected). • The release of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from the melting of the Arctic tundra could result in massively higher carbon concentrations in the atmosphere, triggering a feedback loop of warming temperatures melting more ice and releasing more methane. • The omission of potential feedback mechanisms from some climate change models may lead to an underestimation of risk. Coping with change: adaptation & mitigation Different approaches Adaptation and mitigation are the two key responses; and there are also different types of mitigation target. Mitigation means slowing global warming by tackling the underlying problem of the build-up of GHG, e.g. by switching to renewable energy sources. Adaptation Carbon intensity means dealing with the consequences of climate change, for instance by strengthening flood defences. is a measure of how much carbon dioxide is produced in relation to GDP. A country like China whose GDP is rising can partially mitigate by decreasing the carbon intensity of its GDP as that figure rises - but total emissions still rise. Coping with change: a global agreement (1) Pre-Kyoto • Global concern about climate change has been mounting since the late 1980s. • In 1988, the UN Environmental Programme and the World Meteorological Organisation set up the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). • At the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, 190 countries signed a treaty agreeing that the world community should ‘achieve stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations’. • In 1997, world leaders met again in Kyoto in order to develop the treaty further into a more detailed biding agreement known as a protocol. Coping with change: a global agreement (2) Kyoto • The Kyoto Protocol required all signatories to agree to a legally binding GHG emissions reduction target. For instance, the official EU target was 8%, a goal later increased to 20% by 2020. • It failed to achieve its full effect partly because it was not originally supported by the USA. • The exemption of emerging economies from seeking binding targets became a serious weakness when China overtook the USA to become the world’s largest carbon emitter. • The Kyoto Protocol expires in 2012. Any new pact will be groundbreaking if it can bring together for the first time developed and rapidly emerging economies with legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Coping with change: a global agreement (3) Copenhagen & Cancún • At the 2009 Copenhagen summit, developed and developing country governments agreed to try to prevent temperatures rising more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. • But the pledges made were not legally binding. • Talks in Cancún took the accord reached at Copenhagen a stage further. Countries agreed: to try and set up a “green fund” that will distribute money to help poor countries cope with climate change; increased international co-operation on low-carbon technology; more help for developing nations preserve their forests. Coping with change: roles of key players Carbon stock and flow In 2005, much of the extra CO2 already added to Earth’s atmosphere has come from developed countries. This is called the carbon stock. Developing countries are not as responsible for this legacy. Between 2005 and 2030, much of the new CO2 being produced will come from developing countries – this is called the carbon flow. Coping with change: views of key players Superpower pledges Pledges of the global superpowers European Union has made a binding pledge to cut its emissions by 20% by 2020 (compared with 1990 levels). United States Is still the world’s second biggest carbon dioxide emitter, producing 5,900 million tonnes of CO2 (e) each year. No binding pledge yet. China has a 2020 target to reduce the carbon intensity of its fastgrowing GDP. GHG emissions in 2020 will be 40% higher than today, but lower than they might otherwise be. India has set a non-binding target of 24% reduction in emissions intensity is sought by 2024, equal to savings of nearly 2000 mtCO2(e). Coping with climate change: progress report Technological fix needed ? • “BY 2030, three-quarters of all humankind may have moved to the cities. An estimated 3 billion will live in slums without access to sanitation, clean water, public transport, medical clinics or schools. Their lives are likely to be neither comfortable nor – if the link between extremes and climate change is a real one – long. Six of the planet's 10 most populous cities are already vulnerable to cyclone, flood or tsunami. But extremes of heat, and the consequent increase in urban air conditioning, are likely to make future heat-waves even more lethal.” (Guardian newspaper) • “The world is neither willing nor able to go cold turkey when it comes to ending its addiction to fossil fuels. The problem, particularly for China, India, and the rest of the developing world, is that there simply are not any affordable alternatives. We need to increase spending on green-energy research by a factor of 50.” (Bjørn Lomborg, director of the Copenhagen Consensus Centre) • • • • • • Data from Met Office Illustrations from Financial Times (with permission) Reporting from Financial Times & Guardian http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/5b76b578-04d3-11e0-a99c00144feabdc0.html#axzz19zSp4IH8 http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/72993406-b398-11df-81aa00144feabdc0.html#axzz19zMi0HaR http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ec28be44-061e-11e0-976b00144feabdc0.html#axzz19zSh9NLP