The Neoclassical French Theater

advertisement

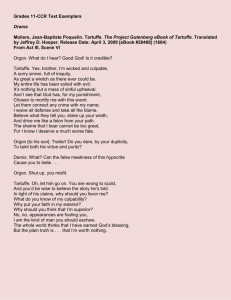

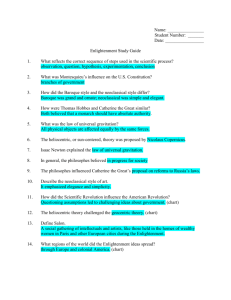

The Neoclassical French Theater The neoclassical French theater’s conventions were inspired by the classical drama of Greece and Rome. Hence the term neoclassical to describe it. Like its ancient antecedents, the seventeenth-century French theater observed the ancient unities: the unity of time, a stipulation that a play’s action be confined to a twenty-four hour period; the unity of place, a single setting; and the unity of action, a single plot. Moliere’s Tartuffe honors all three. Plays that violated the unities were thought to be crude and inelegant by the educated neoclassical audience, which consisted largely of courtiers and aristocrats and well-to-do merchants. Tartuffe was performed for the court of Louis XIV. French neoclassical plays sometimes reflected the ideas and upheld the values popular among these classes; sometimes they satirized them. In either case, the good manners, wit, and common sense of neoclassical comedy mirrored the aristocratic world and suited its audience. The neoclassical stage differed from the stages of Shakespeare and Sophocles in being an indoor theater with a pictureframe stage. The proscenium arch with its curtain separated audience from actors. Neoclassical plays were enacted on a box stage, which represented a room with a missing fourth wall, allowing the audience to look in on the action. The scenery was not elaborate. It was painted and served as a backdrop for the action. Candles and lanterns illuminated both the actors and the audience. Costumes tended toward the elaborate and ornate as in Elizabethan drama. On both the Elizabethan and neoclassical stages actors were ordinarily costumed in contemporary dress that was appropriate to the social status of the characters. A major difference between neoclassical and earlier drama was that female actresses assumed women’s roles, enabling playwrights to include more extensive, more frequent, and more realistic love scenes than had been possible previously (since boys had assumed women’s roles in Shakespeare’s time). As in the earlier eras of drama, however, language still did much of the work, so that even though the intimacy of the French neoclassical playhouse – with a capacity to seat perhaps four hundred spectaors – allowed for refinements of facial and physical gesture, action remained subordinate to dialogue. Moliere Moliere was a poet and an actor as well as a playwright. He performed in his own plays, playing Orgon in Tartuffe. Moliere’s genius was limited to comedy. His comedies were satiric rather than romantic. Moliere was the king of farce. He was the most influential playwright of the neoclassical period, and had the largest impact on playwrights after his time. He freely admitted to depicting the failings of humans truthfully. He used farcical characters to depict true character-types of the time period, and was persecuted for attacking human weakness. He utilized the criteria of the Académie, as well as neoclassical language (he often used rhymed couplets). Another characteristic of neoclassical theatre that is often apparent in his plays is deus ex machina. In two of his most popular plays, Tartuffe and The Would-Be Gentleman, the conflict is resolved in the end with a letter arriving from the king solving all the problems and providing closure to the story. Molière also had his own theatre troupe, and their theatre was called the Palais Royal. In 1665, Louis XIV made Molière's troupe “The Kings Men." He died in 1673 while acting in The Imaginary Invalid . Because he was associated with the theatre, he was refused a Church burial. Louis became upset and, in the end, Molière was buried at night in a small parish. Not long after his death, in 1680, Louis consolidated the Molière-Marais group, which was entitled the Comedie Francaise, the first (and still existing) national theatre. Tartuffe satirizes both religious hypocrisy and fraudulence. It also pokes fun at the obsessive fanaticism and the blind gullibility of those who allow themselves to be victimized by the greedy and the selfserving. When Tartuffe was first staged in 1664, it stirred up those who considered it an attack on religion. Moliere retitled it The Imposter to indicate that Tartuffe’s piety is fraudulent, the original version of the play was censored and banned. To defend himself and the play against charges that Tartuffe attacked religion, Moliere wrote three prefaces and later changed his original ending. The publicity enhanced the play’s o\popularity, and the work was returned to the stage under the protection of the King. Its three-hundred-year-plus life span, however, is due neither to royal protection nor to notoriety, but rather to the ingenuity and vitality of its plot, the profundity of its characterization, and the brilliance of its language, unerringly translated by Richard Wilbur into rhymed iambic pentameter couplets. DiYanni, Robert. Literature Reading Fiction, Poetry, Drama, and the Essay. Boston, Massachusetts, 1998. Alvin Goldfarb. Bibliography: A. Houssaye, Behind the Scenes of the Comédie Française (1889) H.C. Lancaster, The Comédie Française, 2 vols (1941; 1951).