Keys to Effective Lecture

advertisement

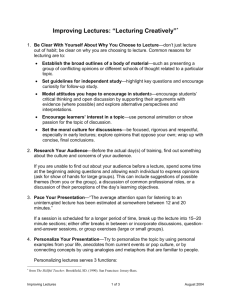

Keys to Effective Lecture Eight Steps to Better Teaching Developed by Terry Doyle Faculty Center for Teaching and Learning Ferris state University Effective Lecturing Successful Teaching is 80% Planning (Dr. Kitty Manley) Definition of Effective Lecture Lecture should be used and is most effective when it presents information students can not easily learn on their own. Definition of Effective Lecture Information that is complex and difficult to understand is a candidate for lecture. Information that requires a professional to organize it so it can be understood by novices likely needs to be lectured. Definition of Effective Lecture The most effective spoken tools for helping students to understand lectured material are analogies, metaphors, similes, and examples that represent concrete images that connect to the students’ backgrounds Definition of Effective Lecture An effective lecture includes the use of images that illustrate the concepts and ideas being discussed. Images are among the most powerful teaching tools available. Vision is central to any concrete experience we have. In many ways, our brain is a “seeing” brain ( James Zull p. 137) Eight Steps to Effective Lecture 1.Know your audience (students) 2.Have a map to follow (lecture outline) 3.Grab the students’ attention (have a beginning) 4.Recognize students’ attention span 5.Plan an activity for students (have a middle) Eight Steps to Effective Lecture 6.Use visual aids/voice/movements/technology 7.Have a conclusion (an end) 8.Have students do something with the lecture material (Accountability) Step One—Know Your Audience Know students names Know their learning styles—they probably do not learn the way you do. Ask them what their strengths and weaknesses are as learners. Know their attention span limits-it’s not very long Know why they are taking the course-is it required? Know their background knowledge (content and/or skills) Build Community in the Classroom Students need to feel safe, valued and challenged Let them know diverse perspective are encouraged and valued Choices on what and how to learn should be given to students when ever possible (Zimmerman 1994) Remembering that learning is a social/emotional process as well as a cognitive process (How People Learn, 2000) Step 2—Have a Map to Follow 1. Be guided by the underlying principles of the course, the most important cognitive functions and the most important content 2. Identify Significant Questions that the course will answer (Project Zero, Harvard School of Education) 3. Provide a daily lecture outline that: provides a visual outline of the lecture provides a meaningful context for the lecture material provides an organization to the lecture material Giving Homework/Assignments Give the homework or other important out of class information at the beginning of class Step 3—Grab the Students’ Attention Every lecture needs a beginning that does some of the following: engages the audience prepares the audience builds curiosity creates challenge states a question offers a problem outlines the audience’s role sets expectations Attention Grabbers The first five minutes of attention are the best five minutes—use them wisely personal experience story joke/cartoon challenge/problem/question tests or quizzes the unpredictable dress/movement/voice surprises Using Humor to get Attention Wow! “If we learn from our mistakes, I ought be a genius by now” George Abbott cartoon Humor gets Attention I was thinking of something more on paper Imagine More Ferris State University Step 4—Recognize the Attention Span(s) of Students Reasons for short attention spans? Studies with college students and adults show that the brain doesn't work as well when it focuses on more than one task. If the challenge demands a lot of attention, mental performance is particularly poor David Walsh of the National Institute on Media and the Family, Reasons for short attention spans? "Students have a very short attention span, " she says, "in part because of the media that we as teachers and parents have encouraged them to spend their time with, and in part because we haven't taught them to have longer attention spans." Naomi Baron, the American University linguistics professor 10-15 minutes is what to expect Attention Span(s) of Students Secondly--Since the images our media uses change rapidly-- so does the shift of the student’s attention. ( Vincent Ruggerio , A Guide to Critical Thinking) www.java2s.com/Code/JavaImages/JFreeChartMult... www.java2s.com/Code/JavaImages/JFreeChartMult... Attention Spans The student, not a scriptwriter or producer, determines how long he or she will attend to individual tasks. (James Zull, The Art of Changing the Brain) The current generations’ expectation is to be entertained—saying they should not be this way is not the answer. Step 5—Plan an Activity for the Students in the Middle of the Lecture Break up lectures by using small 2-3 person groups to write, discuss, summarize, or solve a problem related to the lecture Have students rise up and stretch at the mid-point of the lecture-breathing is good for the brain Step 5—Plan an Activity for the Students in the Middle of the Lecture Lecture with an end of class quiz every day—research has shown this to raise long term retention of course material (http://www.accd.edu/sac/history/keller/ACCDitg/SSnote.htm) Have students prepare study questions before lecture and then discuss them at the mid point of the lecture for 10 minutes Step 5—Plan an Activity for the Students in the Middle of the Lecture Have a Question Box in the class with discussion topics related to the lecture—pull one or two out at the mid point and have a 10 minute discussion Have students write a test question or a study guide question based on the first part of the lecture The key is that the activity is meaningful and relates to understanding the lecture material. Step 6—Use Visual Aids/Voice/Movement and Technology to Hold Attention and Enhance Understanding Visual aids: 1.Should attract and hold the students’ attention. 2. Should aid the organization, illustration and clarification of the lecture. 3. Should encourage active thought—but not be a distraction. 4. Should increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the presentation. If teaching about the brain this image is helpful www.cyh.com/HealthTopics/Library/brain.gif When Using Visual Aids Don’t… Don’t talk to your slides—all the audience will know about you is what the back of your head looks like. Let the slides speak for themselves. Don’t read the slides word-for-word. It will bore the students and is redundant. Don’t put too much information on any one slide. When Using Visual Aids Pause after highlighting points on a slide. Give students time to absorb the information A lecture is not an exercise in note taking—students should not spend time writing large amounts of information from overheads or slides—when students are writing they are not listening Remember you are the central force behind your lecture not your slides Voice and Movements Not many of us are motivational speakers—but we don’t have to be boring In planning the lecture include thinking about where you can use your voice for emphasis, demonstration, exaggeration, surprise etc. Students sitting in the back should be able to hear you clearly Use your voice as an attention getting tool Don’t talk to the chalk/white board Movements The average TV commercial changes the camera angle (and therefore the focus of the viewer) 15-30 times in 30 seconds. Students today are conditioned to expect changes in their viewing focus. The location of where we hear information (episodic memory) is one of many memory aids students can use. Movements Your location in the classroom can force students to pay closer attention—especially if you are standing right next to them. www.bath.ac.uk/.../summerschool/images/lab2.jpg Step Seven—Have a Conclusion to the Lecture Lectures should be planned to have an ending—not just a last word for that day The ending might include: 1.A summary of the days main points 2.A recap of the questions that were answered that day 3.The solution to the problem for that day Step Seven—Have a Conclusion An activity for the students A one sentence summary A written accounting of the most important point/or most confusing point A one question quiz Listing of test worthy information from that days lecture A chance for students to ask questions Step Eight—Have Students do something with the Lecture Material Current memory research indicates that most learning occurs OUTSIDE the classroom when students read, reflect, write or experience the information given in lecture. (Sprenger, 2005) The sooner and more often students engage with the material the more likely they will learn it. Example—For most students a minimum of 3-5 uses of semantic information is needed for that information to form long-term memories (Sprenger 1999) What should students do to learn the lecture material? Write summaries of the lecture material Make mind maps of the information Answer question about the information Prepare for a quiz on the information Make up test questions from the information Write in a journal/reflect on the information Step Eight—Have Students do something with the Lecture Material The key is the more the students use the lecture information the better they will retain it. The more they think about how the lecture information connects to what they already know the deeper their understanding will become. Final Tips As you lecture stop to check students’ comprehension—the one who does the talking does the learning( T. Angelo)—hear from your students Keep the presentation fresh—vary your classroom routine—a certain degree of unpredictability is a positive motivator Use a multitude of tools to enhance your lectures— role play, guest speakers, video, websites, demonstrations Final Tips Decide in advance when you will take questions and what you will do with questions that require long explanations or are questions not share by many in the class—some can be handled by e-mail Focus on “what concepts need to be taught not what concepts do the students need to know”—lets the students learn on their own those things that they can Limit lecture to 4-5 main points—too much information will result in less understanding –not more Write your test questions the same day you give the lecture to increase accuracy of test questions. The Final Final Tip Fill your lectures with analogies, metaphors and examples that are real world to better connect to the students’ backgrounds The brain is an analog processor, meaning essentially, that it works by analogy and metaphor. It relates whole concepts to one another and looks for similarities, differences, or relationships between them. It does not assemble thoughts and feelings from bits of data (Ratey, 2002, Users Guide to the Brain) References for Effective Lecturing http://www-ctl.stanford.edu/teach/handbook/chklstefflec.html http://www.uoregon.edu/~tep/library/articles/lecturing.html http://www-ctd.ucsd.edu/hndbk/9lect.html http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/MinnCon/lecture1.html Andrews, P. H. ( 1985). Basic Public Speaking. New York: Harper and Row. Baird, J.E. (1974). The Effects of "Previews" and "Reviews" upon Audiences Comprehension of Expository Speeches of Varying Quality and Complexity. Central States Speech Journal. 25, 119127. Beatty, M.J. (1988). Situational and Predispositional Correlates of Public Speaking Anxiety. Communication Education. 37, 28-39. References for Effective Lecturing Frederick, P.J. (1986). The Lively Lecture-8 Variations. College Teaching. 34, 4350. Knapp, M.L. (1976). Communicating with Students. Improving College and University Teaching. 24, 167-168. Lucas, S. E. ( 1983). The Art of Public Speaking. New York: Random House. McKeachie, W.J. (1980). Improving Lectures by Understanding Students' Information Processing. In New Directions for Teaching and Learning: Learning, Cognition, and College Teaching, edited by Wilbert J. McKeachie. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 25-35. Weaver, R.L. (1982). Effective Lecturing Techniques: Alternatives to Classroom Boredom. New Directions in Teaching. 7, 31-39. References for Effective Lecturing Bjork, R. A. (1994) Memory and Metamemory consideration in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds) Metacognition: Knowing about Knowing pp. 185-205. Cambridge, MA MIT Press. Elizabeth Campbell Teaching Strategies to Foster "Deep" Versus "Surface Learning, Centre for University Teaching( based on the work of Christopher Knapper, Professor of Psychology and Director of the Instructional Development Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario References for Effective Lecturing Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York, NY, Grosset/Putnam. Diamond, Marion. (1988). Enriching Heredity: The Impact ofthe Environment on the Brain. New York, NY: Free Press. Damasio AR: Fundamental Feelings. Nature 413:781, 2001. Damasio AR: The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, Harcourt Brace, New York, 1999, 2000. References for Effective Lecturing Sylwester, R. A Celebration of Neurons An Educator’s Guide to the Human Brain, ASCD:1995 Sprenger, M. Learning and Memory The Brain in Action by, ASCD, 1999 How People Learn by National Research Council editor John Bransford, National Research Council, 2000 Kolb, D. A. (1981) 'Learning styles and disciplinary differences'. in A. W. Chickering (ed.) The Modern American College, San Francisco: JosseyBass. References for Effective Lecturing Ratey, J. MD :A User’s Guide to the Brain, Pantheon Books: New York, 2001 Zull, James. The Art of Changing the Brain.2002, Stylus: Virginia Weimer, Maryellen. Learner-Centered Teaching. Jossey-Bass, 2002