Chapter 1 - Bakersfield College

advertisement

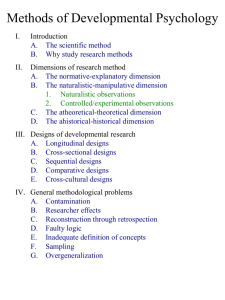

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY AND ITS RESEARCH STRATEGIES WHAT IS DEVELOPMENT? • Systematic continuities and changes between conception to death – Orderly, patterned and relatively enduring – Stability, continues to reflect the past • Developmentalist – anyone who studies the process of development (represent many disciplines) WHAT CAUSES US TO DEVELOP? • Maturation: biological unfolding of an individual – Species-typical biological inheritance – Individual person’s biological inheritance • Learning: experiences producing relatively permanent changes in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors WHAT GOALS DO DEVELOPMENTALISTS PURSUE? • To Describe: based on observation – Normative development – typical patterns – Ideographic development – individual differences • To Explain: addresses the “why” of development • To Optimize: to help people develop in positive directions SOME BASIC OBSERVATIONS ABOUT THE CHARACTER OF DEVELOPMENT • A continual and cumulative process – Change at any phase of life impacts future • A holistic process: development is due to a combination of changes in – Physical growth – Cognitive aspects of development – Psychosocial aspects of development • Table 1.1 A Chronological Overview of Human Development SOME BASIC OBSERVATIONS ABOUT THE CHARACTER OF DEVELOPMENT • Plasticity: capacity for change in response to positive or negative life experiences • Historical/Cultural context – Historical events may influence development – Culture also influences development HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Child in Premodern Times – Active infanticide was practiced prior to 4th century A.D. – Were seen as possessions having no rights – Medieval times – although recognized as a distinct phase of life, little legal distinction was made HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Toward Modern-Day Views on Childhood – Schooling for moral and religious education – Reading and writing also important – Treat children with warmth and affection – Adolescence recognized in the 20th century – Child labor laws passed in late 19th century – Education now compulsory HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Early philosophical perspectives on childhood – Original sin (Hobbes): Children are selfish and must be restrained by society – Innate purity (Rousseau): Children know right and wrong, but society corrupts them – Tabula rasa (Locke): Children are a “blank slate” – experiences determine outcomes HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Children as subjects of study: The baby biographies – Late 19th century, investigators began to observe own children and publish the data • Difficult to compare to each other • Objectivity is questionable • Assumptions may have produced bias • Based on 1 child HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Origins of a Science of Development – G. Stanley Hall – founder of developmental psychology as a research discipline • First large-scale studies of children • Developed the questionnaire • Produced first work to call attention to adolescence as a unique phase of life – Sigmund Freud – psychoanalytic theory HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE • Origins of a Science of Development – Theory: set of concepts and propositions and describe and explain some aspect of behavior – Hypotheses – theoretical predictions which can be tested by collecting data RESEARCH STRATEGIES: BASIC METHODS AND DESIGNS • Careful observation of subjects • Analysis of collected information • Use of data to draw conclusions about how people develop RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • The Scientific Method – Objective: merits of thinking are based on data • Gathering Data: Basic Fact-Finding Strategies – (measuring what interests us) – Reliability: consistent information over time and across observers – Validity: measures what it is supposed to RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Gathering Data – Self-report methodologies • Interviews/questionnaires –Structured: Same questions in the same order »Allows comparison of responses • Table 1.2 Items Comprising Measures of Attitudes Regarding Family Obligations RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Interviews/Questionnaires –Limitations: »Ability to read/comprehend speech »Issues of honesty and accuracy »Interpretation of questions –Strengths »Gathering large amounts of data »Confidentiality improves accuracy RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • The clinical method –Present a task or a stimulus, invite a response. –Follow with a tailored question or task clarifying the response –Flexible approach considering each participant to be unique RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • The clinical method –Strengths »Large amounts of data collected in relatively brief periods »Flexibility –Limitations »Comparison of responses »Subjective interpretation of data RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Gathering Data – Observational Methodologies • Naturalistic observation – observing in common (natural) settings –Strengths: »Very easy »Shows behavior in everyday life RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Naturalistic Observation –Limitations »Rare or socially undesirable behaviors may not occur »Difficult to isolate cause of action or developmental trend »Observer may change behavior (videotape/time may reduce this) • Figure 1.1 Social initiations and negative behaviors of abused and nonabused preschool children. Compared with their nonabused companions, abused youngsters initiate far fewer social interactions with peers and behave more negatively toward them. RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Structured observations –Conducted in the laboratory »Exposed to a setting »Observed surreptitiously »Strength – all participants exposed to same environment »Limitations – results may not represent real life RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Gathering Data – Case study: a detailed portrait of a single individual; can also describe groups • Strength – depth of information • Limitations –Difficult to compare subjects –Lack of generalizability (results may not apply to others) RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Gathering Data – Ethnography: collect data by living within the cultural community for an extended period • Strengths: understanding cultural conflicts and impacts on development • Limitations: subjective, may not be generalizable RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT • Gathering Data – Psychophysiological methods: examine relationship between physiological responses and behavior • Heart Rate – compared to baseline, decrease may indicate interest • EEG – brain wave activity, showing arousal states; stimulus detection RESEARCH METHODS IN CHILD AND ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT – Psychophysiological methods • Limitations –What aspect of stimulus caught attention? –Change in physiology may be hunger, fatigue, or reaction to equipment, not the stimuli. • Table 1.3 Strengths and Limitations of Seven Common Research Methods DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • The Correlational Design – 2 or more variables meaningfully related – Correlation coefficient (r) • Value, +1.00 to -1.00, indicates strength • Sign indicates direction – Positive (+) both variables increase – Negative (-) one variable increases, other decreases • Figure 1.2 Plot of a hypothetical positive correlation between the amount of violence that children see on television and the number of aggressive responses they display. Each dot represents a specific child who views a particular level of televised violence (shown on the horizontal axis) and commits a particular number of aggressive acts (shown on the vertical axis). Although the correlation is less than perfect, we see that the more acts of violence a child watches on TV, the more inclined he or she is to behave aggressively toward peers. DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • The Correlational Design – Correlational studies do not show causation. • Causal direction of relationship is unknown • Relationship could be due to a third, unmeasured variable DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • The Experimental Design – Assesses cause-and-effect relationships between 2 variables – Independent Variable: modified or manipulated by experimenter to measure its impact on behavior – Dependent Variable: aspect of behavior measured in a study, under control of I.V. DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • The Experimental Design – Confounding variable: a factor other than the I.V. that could explain differences in the D.V. – Experimental Control • Control confounding variables • Random assignment – equal probability of exposure to each treatment DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • The Experimental Design – The Field Experiment: an experiment taking place in a naturalistic setting. – The Natural (or Quasi-) Experiment: measuring the impact of a naturally occurring event. • I.V. cannot be manipulated • Participants are not randomly assigned • Figure 1.3 Mean physical aggression scores in the evening for highly aggressive (HA) and less aggressive (LA) boys under baseline conditions and after watching violent or neutral movies. ADAPTED FROM LEVENS ET AL., 1975. • Table 1.4 Strengths and Limitations of General Research Designs DETECTING RELATIONSHIPS: GENERAL RESEARCH DESIGNS • Cross-Cultural Designs – Participants from different cultures or subcultures are observed, tested, and compared on aspects of development. • Studies people of different nationalities, but also groups within the same nation • Guard against overgeneralization of research findings BOX 1.1: FOCUS ON RESEARCH: GENDER ROLES ACROSS CULTURES • Are sex differences in behavior due to biological differences between the sexes? – Arapesh: males and females taught to be cooperative, nonaggressive, and sensitive – Mundugumor: men and women are aggressive and emotionally nonresponsive – Tchambuli: males are passive, dependent, and sensitive, females the opposite RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Cross-Sectional Design – People of different ages are studied at the same point in time • Cohort – group of the same age, exposed to similar environments and cultural events • Figure 1.4 Children’s ability to reproduce the behavior of a social model as a function of age and verbalization instructions. ADAPTED FROM COATES AND HARTUP, 1969. RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Cross-Sectional Design - limitations – Cohort effects – any differences observed may be due to cultural or historical factors that distinguish cohorts, not actual developmental change. – Data on individual development • Each person is measured once, so there is no data on individual development RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Longitudinal Design – Same participants are observed repeatedly over a period of time • Can assess stability of attributes • Can identify normative developmental trends • Can help understand individual differences in development RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Longitudinal Design – Limitations • Costly and time-consuming • Practice effects – improvement due to familiarity with test or interview • Selective attrition – participants remaining in the study may not be a nonrepresentative sample RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Longitudinal Design – Limitations • Cross-generational problem – due to changes in environment, conclusions may be limited to those who were growing up while the study was in progress RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Sequential Design – Selects participants of different cohorts and follows each cohort over time • Strengths –Analysis of cohort effects –Both cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons in same study –More efficient • Figure 1.5 Example of a sequential design. Two samples of children, one born in 1998, and one born in 2000 are observed longitudinally between the ages of 6 and 12. The design permits the investigator to assess cohort effects by comparing children of the same age who were born in different years. In the absence of cohort effects, the longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons in this design also permit the researcher to make strong statements about the strength and the direction of any developmental changes. RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Microgenetic Design – Illuminate processes that promote developmental change • Repeatedly expose children ready for a developmental change to experiences thought to produce that change • Monitor behavior as it changes RESEARCH DESIGNS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT • The Microgenetic Design – Limitations • Time consuming to track large numbers of children in such a detailed manner • Repeated observations may affect the developmental outcomes being studied • Table 1.5 Strengths and Limitations of Four Developmental Designs ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DEVELOPMENTAL RESEARCH • Research Ethics – standards of conduct to protect participants from harm – Informed consent – explanation of all aspects of research that may affect willingness to participate – Benefits to risks ratio – comparison of possible benefits to costs of research in terms of harm or inconvenience ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DEVELOPMENTAL RESEARCH • Research Ethics – Confidentiality – concealment of identity with respect to data subjects provide – Protection from harm – research subjects have a right to protection from physical or psychological harm • Table 1.6 Major Rights of Children and Responsibilities of Investigators Involved in Psychological Research BOX 1.2: APPLYING RESEARCH TO LIFE: BECOMING A CONSUMER OF RESEARCH • Need to know how to evaluate the new findings reported in the media – How were the data gathered? – How was the study designed? – Were the conclusions appropriate for the design? – Were participants randomly assigned?