IV Acetaminophen Research Proposal - Beth Ellen Kalkman

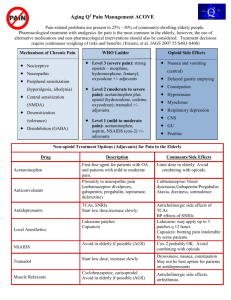

advertisement