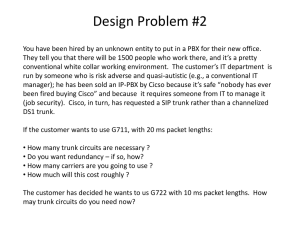

Global economic prospects have continued to deteriorate with the

advertisement