credit policy - McGraw Hill Higher Education

advertisement

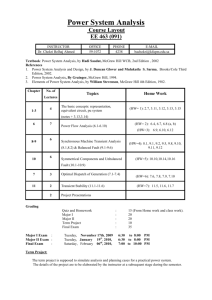

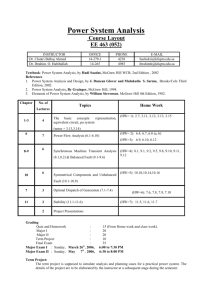

21-1 Fundamentals of Corporate Finance Second Canadian Edition prepared by: Carol Edwards BA, MBA, CFA Instructor, Finance British Columbia Institute of Technology copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-2 Chapter 21 Credit Management and Collection Chapter Outline Terms of Sale Credit Agreements Credit Analysis The Credit Decision Collection Policy Bankruptcy copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-3 Introduction • A/R – A Valuable Asset A few companies ask for cash on delivery when they sell their goods. However, the majority allow a delay in payment. The customers’ promises to pay for their purchases constitute a valuable asset. It appears on the balance sheet as Accounts Receivable (A/R). copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-4 Introduction • A/R – A Valuable Asset Additional customers will be attracted to firms that offer the opportunity to buy on credit. However, there is a cost to the seller who provides this credit. Good credit management involves balancing the costs and benefits of giving the firm’s customers credit. There are a number of steps a financial manager can follow, each of which will be discussed in this chapter. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-5 Terms of Sale • The Payment Terms The terms of sale are the terms under which your firm will sell its products. Does it offer credit, or does it expect cash on delivery (COD)? If the firm gives credit, how long will customers have to pay their bills? Is the firm prepared to offer a cash discount for prompt payment? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-6 Terms of Sale • The Payment Terms Terms of sale will vary from industry to industry, but share similarities within industries. The terms of sale include the following: The seller must supply the buyer with a final payment date. To encourage payment before that date, the seller may offer a discount to the buyer for prompt settlement. If a discount is offered, the seller must indicate how long that discount will be available. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-7 Terms of Sale • The Payment Terms For example, a manufacturer may require payment within 30 days, but offer a 5% discount to customers who pay in 10 days. These terms would be called 5/10, net 30: 5 percent discount for early payment / 10, Number of days discount is available net 30 Number of days before payment is due copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-8 Terms of Sale • A/R as a Loan to Customers A firm that buys on credit is in effect borrowing from its supplier. It will pay later for the products it receives. This is an implicit loan from the supplier. We can calculate the implicit cost of this loan. For example: a supplier offers your firm terms of 3/10, net 30. If your company forgoes the discount and pays for a $100 order on the 30th day, what is the effective interest rate for taking the extra days of credit? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-9 Terms of Sale • A/R as a Loan to Customers The effective annual rate to the firm of foregoing the discount is calculated as: ( Discount Effective Rate = 1+ Discounted Price 365 extra days credit ) -1 copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-10 Terms of Sale • A/R as a Loan to Customers With terms of 3/10, net 30, if your company forgoes the discount and pays on the 30th day, the effective cost will be 74.3%! That is, you obtain an extra 20 days of credit by delaying payment from the 10th to the 30th day. If you had paid within 10 days, the cost of the order would have been $97. By delaying, you will pay $100, or $3 extra. Thus, the extra 20 days of credit costs $3/$97 or 3.09%, which must be compounded to get the annual rate. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-11 Terms of Sale • A/R as a Loan to Customers The effective annual rate to the firm of foregoing the discount is calculated as: ( Discount Effective Rate = 1+ Discounted Price ( ) $3 = 1+ $97 365 extra days credit ) -1 365 20 -1 = 0.743 or 74.3% copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-12 Credit Agreements • Creating the Contract When your firm gives credit to a customer, what should it request as evidence that the customer owes it money? Open Account means that sales are made on credit with no formal debt contract. A promissory note is a simple IOU from the customer. A commercial draft is a an order to pay. A cheque is an example of a commercial draft. It is your order to your bank to make a payment. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-13 Credit Agreements • Creating the Contract A sight draft is a draft which orders the customer’s bank to make immediate payment. A time draft is a draft which orders the customer’s bank to make payment in the future. When a bank receives a draft, it either pays up or acknowledges the debt by adding the word “accepted” and a signature. Once accepted, a draft is like a postdated cheque and is called a trade acceptance. A trade acceptance is forwarded to the seller who holds it until the due date. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-14 Credit Agreements • Creating the Contract The seller can ask the customer to arrange for his/her bank to accept the time draft. In this case, the bank guarantees the customer’s debt and the draft becomes known as a banker’s acceptance. Banker’s acceptances are often used in overseas trade. They are actively bought and sold in the money market for short-term, high quality debt. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-15 Credit Analysis • Measuring Customer Reliability Credit analysis is a procedure to determine the likelihood a customer will pay its bills. There are a number of ways to find out whether customers are likely to pay their debts. Your firm could look at the customer’s past credit history with it. For new clients, your firm could use the services of a credit agency, such as Dun & Bradstreet, to provide reports on the potential customer’s creditworthiness. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-16 Credit Analysis • Measuring Customer Reliability Your firm could ask its bank to perform a credit check on the customer. It would call the customer’s bank and ask for information on their credit history. The firm could check with the financial community. For a public firm, for example, your firm could check its bond rating. For corporate customers, your firm could perform a financial ratio analysis on their financial statements. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-17 Credit Analysis • Measuring Customer Reliability Credit management involves making a judgment about what are often termed the five C’s of credit: Customer’s character. Customer’s capacity to pay. Customer’s capital. Collateral provided by the customer. Condition of the customer’s business. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-18 Credit Analysis • Measuring Customer Reliability Firms will try to streamline the process of dealing with large volumes of credit data by creating a scoring system for prescreening credit applicants. For example, if you apply for a credit card or a bank loan, you will be asked about your job, home, and financial position. The information is used to calculate an overall score. Applicants who do not make a minimum grade may be refused credit or subjected to more detailed analysis. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-19 Credit Analysis • Multiple Discriminant Analysis Multiple discriminant analysis is a technique used to develop a measure of solvency known at the Z Score. The Z-Score is a formula that is able to identify bankrupt firms with a high degree of accuracy: Z= 3.3 EBIT Total Assets +1.4 Sales +1.0 +0.6 Total Assets Retained Earnings Total Assets +1.2 MV of Equity Total Book Debt Working Capital Total Assets copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-20 Credit Analysis • Measuring Customer Reliability Credit analysis is worthwhile only if the expected savings exceed the costs. Don’t undertake a full credit analysis unless the order is big enough to justify it. Don’t spend $200 to do a credit check for an order with a maximum profit of $100. Undertake a full credit analysis for the doubtful orders only. Only borderline applicants should be subject to a full-blown credit check. Other applicants should be quickly accepted or rejected. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-21 The Credit Decision • Setting a Credit Policy A credit policy is a set of standards for determining the amount and nature of credit to extend to customers. If there is no probability of a repeat order, the credit decision is very simple: The firm can refuse credit and pass on the sale. Thus, profit = 0. The firm can offer credit. If the customer pays, the firm benefits by the profit margin. If the customer defaults, the firm loses the cost of the goods delivered. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-22 The Credit Decision • Setting a Credit Policy You can see the decision tree for this problem in Figure 21.1 on page 637 of your text. The expected profit from the two sources of action are as follows: Refuse Credit: 0 Grant Credit: p x PV(Rev – Cost) – (1-p) x PV(Cost) The firm should grant credit if the expected profit from doing so is positive. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-23 The Credit Decision • Setting a Credit Policy If you set the “grant credit” equation to zero, then the breakeven probability of collection is: p= PV(Cost) PV(Revenue) For example: Cast Iron Company (CIC) earns revenues with a present value of $1,200. The present value of its costs are $1,000 on each non-delinquent sale. Under what circumstances should CIC grant credit? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-24 The Credit Decision • Setting a Credit Policy For CIC, the expected profit from the two sources of action are as follows: Refuse Credit: 0 Grant Credit: p x PV(Rev – Cost) – (1-p) x PV(Cost) = p x PV(1,200-1,000) – (1-p) x PV(1,000) Setting this equation equal to zero, means that p = 5/6. In other words, CIC should grant credit whenever the chances of collection are better than 5 out of 6. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-25 The Credit Decision • Setting a Credit Policy The above analysis assumes that the client gives the firm only one order. What happens to the credit decision if there is the possibility of profitable repeat orders? Under these circumstances, the PV(Rev-Cost) increases substantially. Thus, the firm can afford to accept a customer who would have been unacceptable had there been the potential for only one order. Try Example 21.4 on page 638 of your text. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-26 The Credit Decision • Some General Principles Maximize profits As a credit manager, you wish to maximize profits, not minimize the number of bad accounts. You must weigh the benefits of gaining an additional sale against the losses from a defaulting customer. If the expected margin of profit is high, then you are justified in a liberal credit policy. If the margin of profit is low, you cannot afford many bad debts. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-27 The Credit Decision • Some General Principles Concentrate on the Dangerous Accounts Do not waste time analyzing every credit decision. Most decisions will be a routine accept-reject. Only the large and/or dubious decisions will require a detailed credit analysis. Many companies set a credit limit for each customer. The sales rep refers the order for approval only if the customer exceeds this limit. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-28 The Credit Decision • Some General Principles Look beyond the immediate order Sometimes it is worth accepting a marginal customer if there is a likelihood that they will become a regular and reliable buyer. Incurring bad debts is part of the cost of building a good customer list. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-29 Collection Policy • The Problem of Collecting If credit is granted, the next problem is setting a collection policy. A collection policy is the firm’s procedures to collect and monitor its receivables. Recognize that some clients are going to fail to pay their bills on time. How will you deal with them? This question requires tact and judgment. You need to be firm with delinquent customers, but you do not wish to offend a client whose cheque has merely been delayed in the mail. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-30 Collection Policy • The Problem of Collecting You will find it easier to spot troublesome accounts if you keep a careful aging schedule of outstanding accounts. An aging schedule involves classifying the firm’s accounts receivable by the time outstanding. An example of an aging schedule can be seen in Table 21.1 on page 640 of your text. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-31 Bankruptcy • When things go wrong … What happens when a firm cannot pay its creditors? A firm that cannot meet its obligations can try to arrange a workout with its creditors to enable it to settle its debts. A workout is an agreement between a company and its creditors establishing the steps the company must take to avoid bankruptcy. If the workout is unsuccessful, the firm may have to declare bankruptcy. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-32 Bankruptcy • When things go wrong … Bankruptcy is the reorganization or liquidation of a firm that cannot pay its debts. Liquidation involves the sale of the bankrupt firm’s assets. The alternative to liquidation is reorganization. Reorganization is a restructuring of the financial claims of the firm to allow it to keep operating. It involves keeping the firm as a going concern and compensating the creditors with new securities, including equity. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-33 Bankruptcy • When things go wrong … Restructurings are often successful and the company re-emerges fit and healthy. However, other times it fails and the company ends-up being liquidated. Ideally, a firm should be worth more as a going concern than it would be in liquidation. However, conflicts between the objectives of keeping the company alive and protecting the lenders can lead to the process failing. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-34 Summary of Chapter 21 The first step in the credit management process is to set the terms of sale. This means you decide the length of the payment period, the size of any discounts and how long the discount will be available. Such terms are usually standardized by industry. Your next step is to decide the form of the contract with your customer. Most domestic sales are on open account, meaning there is no formal written contract of the customer’s debt for the goods. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-35 Summary of Chapter 21 The third step is to establish a procedure for determining each client’s creditworthiness. The fourth step is to establish a collection policy to identify and pursue slow payers. This requires tact and judgment: being firm with delinquent clients without offending a client whose cheque has been delayed in the mail. Credit analysis is the process of deciding which clients will pay their bills. There are various sources of such client information, including the firm’s own records, credit agencies, banks and analyzing the customer’s financial statements. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 21-36 Summary of Chapter 21 The job of the credit manager is to maximize profits, not to minimize the number of bad debts. You must weigh the odds of payment, and making a profit, against the odds of default and losses. It is often worthwhile accepting a marginal client if there is a chance they will become a reliable and regular customer. When a customer fails to pay, solutions range from a workout to bankruptcy. Bankruptcy may involve reorganization or liquidation. Conflicts between parties, can lead to the usually less desirable option of liquidation. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited