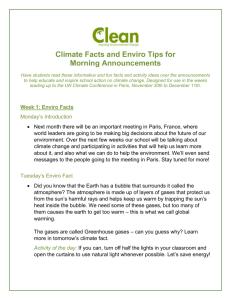

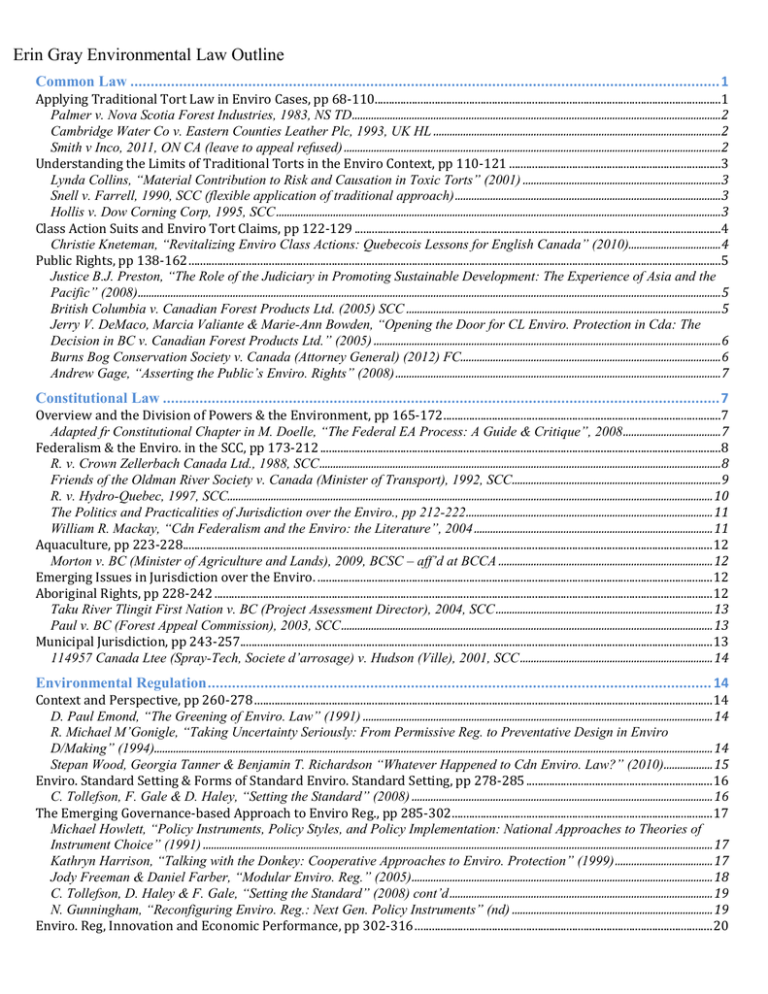

- UVic LSS

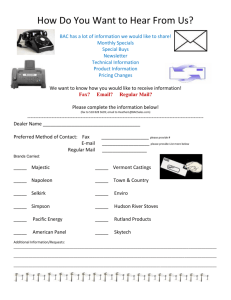

advertisement