WEEK 6 - Home Page

advertisement

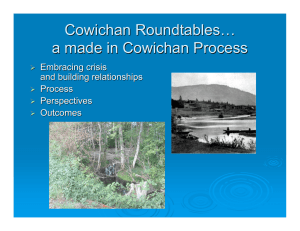

PLAN 502: WEEK 6 The Tail End of Hudson, “Wicked Problems,” and Communicative Rationality Housekeeping Items • I have your outlines and I’m working away on them, but I’m swamped with marking and getting ready to move so I can’t promise to get them back as soon as I would like. • The policy assignments are due on the 28th. • I will probably re-arrange the last two or so weeks of class so we have more time to hear from Maria Inês on environmental policy in Brazil. • Reminder: 10th Urban Issues Film Festival will be on Friday, November 6th on campus for from 3 to 9 (food provided at 5 p.m.). Hudson – Last Few Pages • It will be in Building 356, Room 109 (the auditorium) and will feature short and longer films on the broad theme of housing regeneration. Pre-registration required. • His criterion of public interest: does each tradition have an explicit theory of the public interest, and how does each handle conflict or do they tend to gloss over conflict? • Human dimension: does the tradition in question only acknowledge “objective decision rules,” or does it consider subjective issues of emotions, ideology, politics, aesthetics, and psychology? Hudson – Last Few Pages • Feasibility: The map is not the terrain, but at the same time the map needs to simplify to some degree so that people can understand and plan without oversimplifying. Does each tradition accomplish this? • Action potential: Can the theory of each tradition be carried into action, build on previous experience, and find creative solutions to problems? • Substantive theory: ability to see the bigger picture in space and time, to predict the future and the consequences of various decisions. Hudson – Last Few Pages • Capacity for self-reflection: Which of the traditions seems most able to think critically about its own work and to make changes accordingly. • Which tradition or traditions do you think is strongest in each of these areas? • What kind of planner do you see yourself as being? Synoptic, incremental, transactive, advocacy, or radical? One Might Ask What Do Each of These Traditions Have to Say About “Wicked Problems” • Characteristics of wicked problems: Interlocking issues and constraints – solving one problems can exacerbate or create others Multiple stakeholders with differing views No once-and-for-all, definitive solutions Limited resources and/or political ramifications • As Wikipedia notes, “[t]he use of the term ‘wicked’ here has come to denote resistance to resolution, rather than evil.” • A good example of wicked problems is the challenges Translink has faced in raising the necessary revenue to invest in an enhanced transit system in the Greater Vancouver region. The province recently forced it to hold a public referendum on increased funding, which it lost. “Wicked Problems” • This enabled the province to take the heat off itself for not investing in transit. • When Translink was more autonomous, it tried put a levy of $75 a year on cars. Car drivers protested, it was an election year, and the province put the kibosh on it. • Often it comes down to a matter of subjective perceptions. Transit investments invariably benefit car drivers, Translink’s maintenance program also exists to expand and improve roads. Car drivers don’t subsidize car drivers; it’s the other way around. Car drivers are massively subsidized out of the public purse. “Wicked Problems” • The article I asked you to read – “Come Hell or High Water” from The Globe and Mail – about the likely inundation of south Florida from sea-level rise also illustrates wicked problems. The problem is clear and real enough for scientists, but residents are in massive denial: they think their home will be spared, despite their dependence on infrastructure, and think it will only be a problem for future generations. • Unless people are willing to confront an issue how can you address it? • As we discussed in another class of mine, it seems only the tangible experience of a crisis induces people to change their views, and even then there’s no guarantee. “Wicked Problems” • Cities in Canada receive only about 8% of all tax dollars collected by all three levels of government. • Unlike American cities, they have few mechanisms for raising revenue – property taxes, permit fees, and development cost charges. And, like their American brethren, Canadians don’t like anything that smacks of additional taxes; hence Translink’s problems. • Another example of a wicked problem is when a left-leaning government wins an election and wants to make significant changes in policy and risks divestment by corporations and loss of credit by the International Monetary Fund, thus potentially resulting in the crippling of the economy. “Wicked Problems” • It has been suggested that three strategies for solving wicked problems is to a) restrict the number of decision-makers; b) have groups compete in coming up with alternative solutions, or c) collaborate to find solutions with all relevant stakeholders. Each of these approaches has up sides and down sides. • How do we go from wicked problems to positive solutions? I don’t have any definitive answers, but I think we need to address all four systems in model simultaneously – for instance, building transitfriendly, not automobile-dependent neighbourhoods, building cities that have a smaller ecological footprint, and trying to educate people to have want different things. John Forester • In his most famous text, Planning in the Face of Power, Forester says that “[p]lanning is the guidance of future action” (elsewhere he says it is the linking of knowledge and action). • He notes that planners do not work “on a neutral stage, an ideally liberal setting in which all affected interests have voice; they work within political institutions, on political issues, on whose most basic technical components… may be celebrated by some, contested by others” and where some people have way more resources and access to information and influence than others. • “In a world of conflicting interests – defined along lines of class, place, gender, organizations, or individuals – how are planners to make their way.… [H]ow are planners supposed to respond when private profit and public wellbeing clash?” John Forester • He notes they are supposed to organize public participation in bureaucratic organizations that may be threatened by such participation. • In this chapter in the text, he distinguishes between dialogue, debate, and negotiation, and the need to facilitate the first, moderate the second, and mediate the last. The last should achieve “win-win” rather than “lose-lose” outcomes. • He makes a statement on p. 207 I’m not sure I agree with: “The social sciences seem more taken with ‘physics envy’ than with any growing respect for applied work. Our professional schools remain riddled with antiintellectualism, with theoretical fads disconnected from the entanglements and challenges of practice, and with conceptions of ethics that reduce normative thinking to simplistic pronouncements of ideals.” John Forester • He is a fierce opponent of traditional public process: decide, announce, and defend. • He has a matrix with one column headlined by “High Voice/ Participation,” which can result in either effective mediated negotiations or poor negotiations as represented by boisterous public hearings. • The second column is “Low Voice/ Participation,” with effective negotiations in the form of dealmaking (not necessarily representative), or weak negotiations in the form of bureaucratic procedures. Can you think of examples of each? John Forester • He poses the question on p. 208: “how to marry substantial participation, perhaps representing generations yet to come and non-human wellbeing of course too, with effective negotiations that create value and do not squander it, value here including concerns including justice no less than those with health and environmental quality.” • There are positive examples – for instance, the Cowichan Watershed Stewardship Roundtable and the Nanaimo River Watershed Roundtable. I believe someone from this class is involved with the latter. John Forester • Forester is from the “communicative rationality” school, which the editors of the book have been critical of. He assumes that in policy debates in public forums, participants need to ask, when listening to an eloquent advocate for a particular position/ policy: What are they advocating for and is the evidence there to support her claims? Does the government have the authority to implement the policy? Does the political support exist to make her recommendations feasible? And Who is she and what gives her credibility to make these statements? John Forester • If one were looking at the phenomenon of suburbia, one would have to a)try to ascertain the positive and negative aspects of suburbia from a fact-based point of view; b) consider the relevant issues [These two are linked; if you don’t care about nature and other species, then the impact of suburbia on ecosystems will be outside one’s cognitive frame of reference.] and c) phenomenology, which refers to understanding human viewpoints from the inside outside out – why do some people like suburbia, what does it mean to them, and how does it fit into their sense of identity? John Forester • There is a very useful passage on p. 211: “In dialogue… we seek understanding and knowledge of the other. In debate, whether about the ‘facts’ or justification, we do something else again: we’re seeking to establish or refute an argument. In negotiation or cooperation, however, we’re doing something yet different again: we’re seeking an agreement on a course of action (when no established Authority can simply impose an outcome).” • “…mediators seek to manage interdependence, to build relationships, to craft agreements on action to change the world.” One possible example of Forester’s model: The Cowichan Stewardship Roundtable • It is made up of very diverse stakeholders: • In attendance at a recent meeting were Meg Loop (CLT), Keith Lawrence & Kate Millar (CVRD), Paul Rickard and Ted Brookman (BCWF), Parker Jefferson (One Cowichan), Ian Morrison (CVRD Area F), Klaus Kuhn (Area I), Eric Marshall & Carol Hartwig (CVNS), Don Closson (BC Parks), Shaun Chadburn (North Cowichan), Genevieve Singleton (nature interpreter), Chris Morley (Friends of the Cowichan), Ray Demarchi, (retired wildlife biologist), Alistair MacGregor, Peter Julian, Joshua Berson, Jennifer Hermary, and Jean Crowder (fed. NDP), Rod Carswell, Jean Atkinson & Di Gunderson (CLRSS), Barry Hetschko and Martha Lescher (SMWS), Dave Lindsay (Timberwest), Ken Epps (Island Timberlands), Ken Clements & Claude Theirault (Sidney Anglers), Helen Reid & Natalie Anderson (Cowichan Tribes), Brian Tutty (retired fisheries biologist), Tom Rutherford (DFO), Swarn Leung (HUB committee of concern for Koksilah watershed), Goetz Schuerholz (CERCA), Ron Diederichs (BC-FLNRO), Doug Routley (MLA Nanaimo-N. Cowichan), Brian Houle (Catalyst), In addition to the Roundtable… • In addition to the organizations mentioned, there is the Cowichan Lake and River Stewardship Society and the Cowichan Watershed Board formed to oversee and direct the implementation of the Cowichan Basin Water Management Plan. “The • mandate of the Board is to provide leadership for sustainable water management to protect and enhance environmental quality and the quality of life in the Cowichan watershed and adjoining areas. The Board is unique in that it is a partnership between Cowichan Tribes and local government (the CVRD) in conjunction with the federal and provincial governments. It is co-chaired by an elected member from each of the CVRD and Cowichan Tribes.” See http://cowichanwatershedboard.ca/. • However, it has no representation from conserva-tion or environment groups. Alaska Fisheries • Pre-statehood, the US government managed the Alaskan fishery. In 1938: there was a harvest of 120 million fish. In 1958, a harvest of 20 million. • A year later, Alaska became a state. • For a variety of reasons, by 1972 the harvest was even lower. • It was decided to take action in the form of · limiting the entry of new fishing vessels; · rebuilding wild stocks; · constructing hatcheries; · improving stock enhancement, and · initiating ‘ocean ranching.’ Alaska Fisheries • With ocean ranching one strips the eggs from the brood stock, rears them in a hatchery, then places them in ocean nets for 3-4 weeks offshore away from wild stock migration routes, after which they are turned loose. • Meanwhile, they have spent enough time to become imprinted on the area of the ocean nets to return and are thus easy to scoop up, rather than having to be chased. Alaska Fisheries • In Oregon, where ocean ranching was initiated, it was taken over by Weyerhauser. • In Alaska, the key focus for debate was the hatcheries. There was strong pressure for them to be corporatecontrolled on the argument that governments are inherently inefficient, but the fishers resisted. They didn’t want to see the privatization of the commons. Alaska Fisheries • The state government responded by bringing all the players together to come up with a strategic plan, of which ranching was a key component. • Initially, government took over the hatchery program and made a hash of it (harvests declined to 4 million fish). All gear groups were united in the nature of their critique. • By 1976, Regional Aquaculture Associations had been formed representing fishers and other stakeholders in partnership with the state. One particularly successful one has been the Northern Southeast Regional Aquaculture Association (NSRAA). Alaska Fisheries • The organization has achieved its goal of having 85% of fish produced in the area being harvested as a common resource, as opposed to by corporations. • The hatcheries, now operated by non-profit organizations, are costly to run, as are the rest of the management and decision-making activities. • Conventional banks would not look at them, so Alaska set up a State Fisheries Enhancement Loan Fund to extend long-term loans with holidays on the interest and principal. However, this was inadequate, so the fishers demanded that they be subjected to a 2-3% tax on all landed fish to further contribute to the shared infrastructure. • By 1980, the NSRAA had paid off its original loan. Alaska Fisheries Model • The benefits of the model: It seems to protect and enhance the fish stocks. The benefits stay mostly with fishers and their communities. It avoids the ‘tragedy of the commons’ (actually open access systems that Garrett Hardin mistook for the commons), and It keeps control largely in the hands of those most affected. It was achieved by negotiation. Patsy Healey • Healey reviews the origins of planning in modernism and the desire to tame the irrationalities of the market, the power of big capitalist companies, and the chaos of industrial cities. • Planners wanted to bring ‘scientific knowledge’ and instrumental rationality to the solution of problems (finding the means to address the desired ends). • She divides planning into three traditions: economic planning, planning for the physical development of cities and towns, and public administration and policy analysis. What would examples be of each? Patsy Healey • One example of economic planning would be the command and control model of centralized state planning that emerged in the Soviet Union and Maoist China. This proved inefficient, degenerated into the politics of “meeting targets” irrespective of reality, and proved prone to corruption. • Others, more akin to anarchists or left-wing libertarians rejected this model and aimed for decentralized, more autonomous development. Ebenezer Howard was influenced by this tradition, as was Patrick Geddes. It’s carried forward into the work of Gandhi and E.F. Schumacher. Patsy Healey • Another attempt to impose a limited form of planning on the market is represented by the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, who argued for measures to increase consumer demand in the face of an economic slump by means of government spending. This was implemented by Roosevelt through his radical (for capitalism) “New Deal” program. • This was a widely accepted doctrine in North America until the end of the ‘70s when Reagan and Thatcher began their ascent to power in the U.S. and the UK. Then “neo-liberalism” became the order of the day. Patsy Healey • This resulted in the slashing of government budgets and massive deregulation of the economy, which was accompanied by the expansion of deindustrialization (jobs going offshore) and expansion of ‘free trade.’ • This set the stage for the worldwide recession of 2007-08, when even Milton Friedman, the guru of neo-liberal doctrine, was forced to admit that he may have been wrong about a number of things. • This period saw an enormous polarization of wealth, with the erosion of the middle class and the increasing emancipation of corporations from government constraint. Patsy Healey • Pam will or has dealt with the different traditions in physical planning, but Healey contrasts a more pastoral ideal in Britain with a greater preference (or at least tolerance) for high-rise living on the continent (overstated). While not universal (think Manhattan), sprawl has been the dominant model in North America, at least since the war. • Healey mentions, in the tradition of understanding the practical policies and politics of communities, the role of what Logan and Molotch called the “the urban growth machine” – essentially an alliance of developers, real estate agents, and local politicians to advance a pro-development agenda. Nanaimo has been a textbook case. Patsy Healey • The rest of the chapter duplicates much of what we have already read about some of the other models of planning – incremental and advocacy. • She also mentions Arnstein’s “ladder of citizen participation,” which you will be covering in Lindsay’s class. • In contrast with Fainstein, she doesn’t believe that knowledge and value just ‘exist,’ but that they have to have to be “actively constituted through social, interactive processes” (p. 230). • She also believes that there are different ways of ‘knowing’ and communicating knowledge – from planning reports to storytelling. How can these be used in planning processes?