MS Job Connect (U) Ltd v DFCU Bank Limited

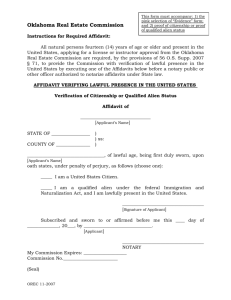

advertisement

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA (COMMERCIAL COURT DIVISION) MISCELLENOUS APPLICATION NO. 627 OF 2014 (Arising out of Civil Suit 483 of 2014) M/S JOB CONNECT (U) LTD:::::::::::: APPLICANT/DEFENDANT VERSUS DFCU BANK LIMITED:::::::::::::::::::: RESPONDENT/PLAINTIFF BEFORE HON. LADY JUSTICE HELLEN OBURA RULING This is an application for leave to appear and defend Civil Suit No. 483 of 2014 brought under Order 36 rule 3 and 4 and 0rder 52 rules 1 and 2 of the Civil Procedure Rules, S.1.71-1 (CPR). It is supported by the affidavit of Doreen Mwesigye, who is stated to be the director in the applicant company. The grounds of the application as I glean from the affidavit in support and affidavit in rejoinder are; firstly, that the respondent continued to charge interest on the loan amount even after the applicant had instructed it not to do so due to its failure to pay the loan which amounts to fraud and breach of contract, secondly, that the respondent delayed for almost a year to sell the security after the applicant advised it to do so which amounts to negligence and resulted to accumulation of a huge debt to it, thirdly, that the respondent continued to charge interest on a non-existent debt after the security was sold and the money recovered and lastly, that the security was sold at an under value hence leaving an outstanding loan value. This application was opposed by the respondent on the grounds stated in the affidavit in reply sworn by Mr. Ruva Edmond Raphael who is stated to be working as the Special Assets Management Executive of the respondent bank. The gists of the grounds in so far as are relevant to the issue under contention are that the applicant acquired an overdraft facility of Ushs. 70,000,000/= with interest which was secured by a mortgage over property whose value the parties mutually agreed 1 as at the time of the mortgage was Shs. 20,000,000/= (open market) and Shs. 15,000,000/= (forced sale). A copy of the valuation report was attached and marked “D”. It is stated further that when the facility expired the outstanding sum immediately became due and payable without further notice or demand but the applicant continued the default and interest continued to accrue. A notice of default was duly sent to the applicant with a demand that the same be rectified within 45 days. The applicant acknowledged default and on 19th September 2012 the respondent gave the applicant 21 working days notice of sale of the mortgaged property. It is further averred that the respondent advertised the mortgaged property for sale three times in the Monitor Newspapers of 10th October 2012, 29th November 2012 and 15th July 2013. Some photocopies of newspaper advertisements were attached and marked “F”, “G” & “H”. The deponent further contends that the respondent carried out another valuation of the mortgaged property which put its open market value at Ushs. 40,000,000/= and forced sale value at Ushs. 23,000,000/= but the property was sold Ushs. 35,000,000/= and the proceeds only covered recovery costs and part of the debt owed leaving an outstanding balance of Ushs. 131,533,158/= as per the copy of the applicant’s statement of accounts which was attached and marked “J”. The deponent averred that the interest charged by the respondent was its contractual rights as provided under clauses 6.1 and 6.2 of the overdraft facility agreement. Furthermore, based on the advice of the respondent’s counsel, that sale of the mortgaged property was conducted within the law and the realization of security offsetting only part of a debt does not release the debtor from liability for the outstanding part of the debt. It was therefore concluded that the respondent’s claim is legal and the application does not disclose a bona fide triable issue of law or fact and the applicant does not have any defence whatsoever to the respondent’s claim. An affidavit in rejoinder was filed by Doreen Mwesigye who reiterated what was stated in the affidavit in support with more emphasis on the continued charging of interest. The respondent was also faulted for not responding to the applicant’s letters at least to communicate its decision to continue charging interest. When this application came up for hearing, the applicant was represented by Mr. Patrick Machika Mugisha and the respondent by Mr. Robert Okalang. Both counsels filed written submissions based on the above grounds. The applicant’s 2 counsel contended that the application raises several triable issues, namely; 1. Whether the respondent/plaintiff acted negligently in going ahead to charge interest on the overdraft facility without responding to the applicant’s requests; 2. Whether it was proper/lawful for the respondent to go ahead and charge interest on the overdraft facility after selling the security; 3. Whether the respondent breached its duty of care in delaying to sell as instructed and in failing to notify the applicant of the outstanding balance on the overdraft facility after sale. It was argued by counsel for the applicant that his client was always willing to settle its debt obligation after receiving notification of the outstanding balance after sale but the respondent never did so and just continued to charge interest with malicious intention of accumulating the debt to the detriment of the applicant. He contended that the applicant also contests the amount claimed on the ground that it includes penal interest and the applicant also contests the rate of interest applied. The applicant’s counsel concluded his submission by praying that the application be granted since it raises issues of law and of fact which must be submitted to a full trial. I must point out at this point that the submission of counsel for the applicant that the applicant contests the amount claimed on the ground that it includes penal interest and the contention that the applicant also contests the rate of interests came from the bar because it is not supported by the applicant’s evidence as contained in both the affidavit in support and that in rejoinder. I will therefore disregard those submissions because they prejudice the respondent’s case and are against the general principle that evidence cannot be given from the bar. In reply to the applicant’s submissions, counsel for the respondent raised two issues namely; 1) Whether the applicant's application for leave to defend is competent. 2) If the application is competent, whether the applicant discloses a bona fide triable issue of law or fact. 3 On the first issue, counsel submitted on a point of law regarding the validity of the affidavit in support of the application. He pointed out that 0.36 r 4 of the C.P.R clearly provides that when the Defendant is served with summons, such defendant shall make an Application for leave to appear and defend that suit and that application shall be supported by an affidavit. He submitted that the legal and mandatory requirement is that there must be an application which must be supported by an affidavit. The affidavit must not therefore be defective and if it is defective, then there is no application and judgment is thus entered. He argued that the instant application is supported by a defective affidavit and as such the application is incompetent and ought to be struck out and judgment entered under 0.36 r 3 of the CPR for lack of an application for leave to appear and defend. His ground for stating so is that the supporting affidavit was commissioned on the 22/7/2014 purportedly by a Commissioner of Oaths called Augustine Ssemakula who as at that date was by law not a Commissioner for Oaths for reason that he had been suspended from legal practice for two years by the Law Council Disciplinary Committee in the case of Ssemakula Augustine vs. The Disciplinary Committee of Law Council, H.C. M.C No. 356 of 2013 and as such that "affidavit" is fundamentally defective and is not an affidavit in law and ought to be struck out. Counsel for the applicant argued that it is trite law that an affidavit must be sworn before a Commissioner for Oaths. He submitted that a Commissioner for Oaths is defined under section l of the Commissioner for Oaths (Advocate) Act as an appointed practising advocate and section l (4) thereof clearly states that every commission shall immediately terminate on the holder ceasing to practice as an advocate. He supported his argument by the case of Professor Syed Hug vs. The Islamic University of Uganda S.C.C.A No. 47/1995, where the Supreme Court held that when an advocate is suspended from practice, his commission to practice as Commissioner for Oaths is terminated. He argued that, therefore, this means that by 22/7/2014, when Mr. Ssemakula purported to commission the affidavit in the instant case, he was under suspension and as such his commission had got terminated and he could not therefore competently commission any affidavit. He concluded that in the circumstances, the 4 affidavit in support is illegal and once illegally is brought to the attention of court it overrides all factors, pleadings and even consents and court cannot sanction and/or condone an illegally. (See the case of Makula International vs. His Eminence Cardinal Nsubuga (1982) HCBII). He argued that consequently, this application is not supported by a valid affidavit as required by law and it collapses and ought to be dismissed with costs and judgment as prayed for in the plaint be entered in favor of the Plaintiff. On the second issue, counsel submitted that it's a settled principle of law that before leave to appear and defend is granted, the applicant / defendant must show by affidavit that there is a bona fide triable issue of fact or law as was held in Maluku Interglobal vs Bank of Uganda (1985) HCB 65. He argued that the applicant in this case does not disclose any triable issue pointing out that the respondent’s continued charging of contractual interest on the outstanding balance, does not raise a triable issue because interest is a contractual obligation. Counsel also argued that it is a well settled principle of law that a party to a contract cannot unilaterally vary it. He submitted that the applicant, at paragraph 3 of its affidavit in support, admits to executing the overdraft facility agreement attached to the respondent's plaint and taking the money thereafter. He quoted clauses 6.1 and 6.2 of the said facility agreement which provide for charging of interest on the amount owed until it is paid in full and argued that the applicant could not therefore unilaterally vary its contractual obligation to pay interest on the amount outstanding as it had no legal basis to instruct the respondent not to charge interest. Furthermore, that the respondent was not obliged to comply with that instruction. On the applicant’s claim that the respondent was wrong to go ahead and charge interest after realizing the security, counsel maintained that the realization of security does not absolve the debtor of the obligation to settle the balance outstanding where the security is insufficient to cover the entire sum owed. He submitted that the respondent at all times informed the applicant of the sums owed as seen in annextures "D" and ".E" of the respondent's affidavit in reply, among other various notifications given to the applicant who was always aware that the sum owed exceeded the value of the security which was valued upon the joint instructions of the applicant and respondent and its open market value was 5 Shs. 20,000,000/= and forced sale value of Shs. 15,000,000/=. On the alleged sale of the mortgaged property below its market value, counsel submitted that the respondent auctioned the security at Ushs. 35,000,000/=, a price over and above its value including its forced sale value under the subsequent valuation and the proceeds covered only the costs of recovery and a small portion of the debt owed by the applicant. He contended that the respondent was entitled to charge interest on the sum outstanding as provided for in clauses 6.1 and 6.2 of the overdraft facility agreement executed by the parties and so this issue too does not merit consideration at trial. On another note, counsel for the respondent had issues with the applicant’s introduction of a new defence in its affidavit in rejoinder which had not been stated in the affidavit in support and other new issues in the submissions that were neither in the affidavit in support nor in the rejoinder. The alleged new defence in the affidavit in rejoinder is that the respondent delayed to sell and as such was negligent. The ones in the submission are the allegation that the respondent failed to notify the applicant of the balance outstanding after the sale and the intended contesting of the rate of interest charged and the interest clauses in the overdraft facility. He submitted that the respondent is greatly prejudiced by the addition of the new allegations in the said affidavit in rejoinder which it has no opportunity to respond to. He urged this court to either disregard the supposed affidavit in rejoinder or disregard the offending paragraphs, specifically paragraphs 4 and 6. On new the matters raised in the submissions, counsel for the respondent submitted that his client did not have opportunity to address them in the affidavit in reply as they were not part of the evidence and as such the respondent would be greatly prejudiced if this court decided this application basing on counsel’s evidence at the bar. He argued that if the applicant intended to rely on them he should have raised them in his application and not in the submissions. In response to the alleged new defence raised in the affidavit in rejoinder, but without prejudice to the foregoing protest, counsel submitted that it is trite law that a mortgagee is at liberty to choose when to sell the security and the only duty the mortgagee owes to the mortgagor is to obtain the true market value of the mortgaged property at the moment he chose to sell it as was stated in Cuckmere Brick Co. vs Mutual Finance Ltd (1971) Ch 949. 6 Counsel contended that in this case the respondent gave the required notices and thereafter immediately commenced on the sale and advertised the property thrice. The subsequent re- advertisements were as a result of offers at the earlier auction failing to materialize and also the offers being low. Furthermore, that the respondent always informed the applicant whenever a sale fell through and the property was to be re-advertised for sale. He submitted that the respondent finally sold the mortgaged property over and above its value. I have carefully considered the above submissions as well as looked at the application with the affidavits and the plaint in the main suit. Before I delve into the merits of this application, I will first deal with the question of law canvassed by counsel for the respondent on the validity of affidavit in support of this application. It is contended that the affidavit in support is incurably defective because it was commissioned by a commissioner for oaths whose commission had terminated upon being suspended from legal practice by the Law Council Disciplinary Committee. Counsel for the applicant in reply submitted that the respondent did not provide evidence of suspension of the advocate to this court in terms of the ruling by the Law Council Disciplinary Committee and the gazette notice and so it remains a mere allegation. He also argued that even if this court were to find that the affidavit is incurably defective it would not make the application it purports to support incompetent because according to counsel, it is not mandatory that an application brought under order 36 rule 4 of the CPR must be supported by an affidavit. He argued further that the word shall used in the rule is merely directory because the rule does not state the effect of failure to support an application with an affidavit. This position was supported by the decision of Tsekooko JSC in Mukasa Anthony Harris vs. Dr. Bayiga Michael Philip Lulume (SC) Election Petition Appeal No. 18 of 2007. Counsel for the applicant urged this court to overrule the objection on the above grounds with costs as there is no evidence to support it. It is not disputed that the applicant’s affidavit was commissioned by Mr. Augustine Ssemakula but the only issue I see is whether or not he had been suspended from legal practice at the time he commissioned the affidavit and, if so, whether the application can stand without the affidavit in support. It is indeed true that the 7 respondent did not provide proof of Mr. Ssemakula’s suspension beyond the citation of the case in respect of which he was allegedly suspended. In view of this serious question of law can this court just fold its hands and merely agree with counsel for the applicant that since no evidence of the suspension had been provided the objection cannot stand? I would say no because questions of illegality are so serious that they require further investigation and action by courts of law. In that spirit I did come across the case of Standard Chartered Bank (U) Ltd vs. Mwesigwa Geoffrey Philip HCMA No. 477 of 2012 arising from HCMA No. 22 of 2011 and HCCS No. 30 of 2010 where the issue of Mr. Semakula’s suspension was raised and ample evidence of his date of suspension was provided before Hon. Justice Christopher Madrama who had this to say in his findings and conclusion of the matter:“The Respondent cannot run away from the import of the submissions of his own lawyers and the binding Supreme Court authority of Prof Syed Huq Versus the Islamic University in Uganda Supreme Court Civil Appeal Number 47 of 1995, graciously supplied to the court. For now the letter of the Chief Registrar gives the information that Augustine Ssemakula was suspended from practice as an advocate for a period of two years with effect from 31 August 2012 and this letter was relied upon by the Respondent’s counsel. I agree with the law which is binding on me and would only consider the affidavit in support of the application by Counsel Paul Kuteesa and disregard affidavits commissioned after 31 August 2012….” It is abundantly clear from that ruling that Mr. Ssemakula Augustine was suspended from legal practice for a period of two years with effect 31 st August 2012. It therefore follows that any affidavit purportedly commissioned by him during the period of his suspension would be incurably defective and court can only strike it out. The affidavit in support of this application was commissioned by Mr. Ssemakula on 22nd of July 2014 a month and nine days before the period of his suspension lapsed on 31st August 2014. In the circumstances, I find that the affidavit in support is incurably defective and it is accordingly struck out thereby leaving the application unsupported. 8 The next question is therefore whether the notice of motion can stand without an affidavit in support as argued by counsel for the applicant. The answer to this question is found in the wealth of authorities that dealt with incurably defective affidavits. They include, among others; Jayantilal Amratlal Bhimji & Another vs Prime Finance Company Ltd, Misc. Application No. 467 of 2007; Kaingana vs Dabo Boubou [1986] HCB 59 and Attorney General vs Kilembe Mines Ltd & Another, Misc. Application No. 702 of 2008) In Kaingana v Dabo Boubou (supra) it was held that:“Where an application is grounded on evidence by affidavit, a copy of that affidavit intended to be used must be served with the action. In such a case, the affidavit becomes a part of the application. The Notice of Motion cannot on its own be a complete application without the affidavit. Therefore in the instant case the Notice of Motion alone was not enough”. [Emphasis mine]. Following the above authorities, I find that this application is incompetent without the supporting affidavit and cannot stand. I have considered the misconceived submission of the applicant’s counsel based on the decision in Mukasa Anthony Harris (supra) and I wish to categorically state that the interpretation of provisions of the law stated in that case is not applicable to Order 36 rule 4 of the CPR which expressly spells out what needs to be stated in the affidavit in support of the application. The mischief intended to be addressed by Order 36 rule 4 is granting an application for leave to appear and defend a suit when actually there is no defence to the claim. The purpose of requiring an application for leave to appear and defend a summary suit to be supported by an affidavit is for the applicant to provide evidence that would convince court that indeed there is an arguable defence to the claim by the plaintiff which merits a full trial. That is why rule 4 of Order 36 mandatorily requires the affidavit to state whether the defence alleged goes to the whole or to part only, and if so, to what part of the plaintiff’s claim. It is therefore the firm view of this court that if counsel for the applicant’s dangerous arguments were to be upheld the mischief would remain and that would defeat the whole concept of summary suits under Order 36 whose rationale was stated by the Court of Appeal of East Africa in the case of Zola v Ralli Brothers Ltd [1969] EA 9 691 at 694 in the following words:“Order 35 is intended to enable a plaintiff with a liquidated claim, to which there is no good defence, to obtain a quick and summary judgment without being unnecessarily kept from what is due to him by the delaying tactics of the defendant. If the Judge to which application is made considers that there is any reasonable ground of defence to the Claim the plaintiff is not entitled to Summary Judgment.” That court was considering the Kenya equivalent of our Order 36 of the CPR under which this application is brought. When you do away with the strict requirement for affidavit in support that states the defence then all applications would have to be granted since there would be no basis for granting some and rejecting others and the purpose of summary suits would not be served. For the above reasons, I find that applications under Order 36 rule 4 are grounded on evidence by affidavit and therefore an affidavit is a mandatory requirement. Any application that does not comply with that requirement like the instant one would be incompetent and I so find. In the result, this application would be struck out with costs. Be that as it may, I have decided to consider the merits of the application based on the assumption that it is supported by a valid affidavit and as such it is valid. I did so for avoidance of multiplicity of proceedings just in case for some reason the above decision is set aside and the applicant decides to again apply for leave to defend the suit on the basis that this application was not determined on the merits. It is indeed a settled principle of law that before leave to appear and defend is granted, the applicant / defendant must show by affidavit that there is a bona fide triable issue of fact or law. This has been repeatedly restated in a number of cases including Maluku Interglobal (supra) cited by the respondent’s counsel. It is therefore the duty of the applicant to satisfy this court that there is an issue or question in dispute which ought to be tried. I have looked at the grounds of this application and the alleged issues that need to be tried and I am not persuaded that they merit wasting courts time to hear them. First of all, the allegation that the respondent continued to subject the outstanding 10 debt to interest yet they had received the money through the sale of the security is misconceived because as long as the loan amount had not been fully paid the respondent was at liberty to continue charging the contractual interest as clearly spelt out in clauses 6.1 and 6.2 of the Overdraft Facility offer letter dated 28th March 2011 whose terms and conditions the plaintiff’s directors Ms. Doreen Mwesigye and Ms. Annet Barlow accepted by appending their signatures thereto on the 30th of March 2011. I therefore do not see any issue for trial as regards the continued charging of interest after a sale that did not realize fully the outstanding debt. Secondly, on the alleged continued charging of interest on the loan by the respondent after the applicant had allegedly instructed it to stop doing so, I find it quite ridiculous that the applicant could even raise such an argument moreover with the help of a lawyer who ought to know better that a party to a contract cannot just unilaterally issue an instruction to the other party to stop doing what the parties had agreed on. If at all the applicant wanted to negotiate waiver of the interest it could not merely write to the respondent and expect it to just comply. It would have taken trouble to initiate meetings with the respondent to discuss the matter. Therefore, it can only fault the respondent if they had negotiated and agreed on waiver of the interest and the respondent again reverted back to the original position. Absence of that agreement, the applicant cannot treat its letter of request to the respondent as an instruction which was not followed. I therefore do not find any merit on this ground that would require a trial. Thirdly, on the alleged sale of the security at an under value, I have not seen the basis for alleging so. It is not in dispute that the value of the property as at June 2009 was Shs. 20,000,000/= (open market) and Shs. 15,000,000/= (forced sale). This was ascertained by a valuation exercise in which the applicant’s director and registered proprietor of the mortgaged property Ms. Doreen Mwesigye is stated in the report to have been present when the inspection of the property was done by the valuer. In clause 12.0 of that report it was stated that the estimated market value of the property on completion of the boys quarters would be Shs. 40,000,000/=. There is no evidence that the boys quarters was completed but four years later another valuation was done after the applicant had cleared the respondent to sell the security to realize its money and the open market value was stated to be Shs. 40,000,000/= while the forced sale value was found to be Shs. 11 23,000,000/=. The respondent then sold it at Shs. 35,000,000/= way above the forced sale value but slightly below the open market value. Surely, can it be said that this property was sold at an under value? It is also quite interesting that the applicant merely wrote to the respondent to sell without even bothering to find out the then market value. If indeed this property was of more value than what the respondent obtained would not the applicant have sought to participate in the sale? To my mind the applicant was not very keen because it knew that the property would not fetch that much money beyond the known value and that is why it even requested to know the balance to be paid after the sale. Besides, the applicant has not attached any document either in terms of valuation report with a higher value or offers to buy the land at a higher price to try and convince this court that the sale was at an under value. For the above reason, I would find that the issue of under value is devoid of any merit and cannot be a ground for granting this application. Finally, on the alleged delay to sell which amounts to negligence, I have looked at the applicant’s letter dated 15th June 2012 by which she requested the respondent to sell the mortgaged property if they failed to make some payments in the following months. The letter did not specify the month but said following months implying that the respondent was to expect payments at least for some months before it could sell. Indeed the respondent waited for some months and on 19th September 2012 it issued a notice of sale of the mortgaged property to recover the debt. The applicant replied on 23rd September 2012 and stated in paragraph one of that letter that:- “We are in receipt of a notice that you will be selling mortgaged property as agreed in the meeting”. It can be deduced from that sentence that the parties had met and agreed on selling the property before the notice was issued. What followed according to paragraph 8 of the affidavit in reply and the annextures thereto was advertisement of the property in the newspaper of 10 th October 2012 less than a month after the notice was issued. Other advertisements were made in November 2012 and July 2013 and the property was finally sold on 16th October 2013. The respondent explained that it did not merely delay to sell but the offers were either too low or there was none and that is why the earlier advertisements did not yield any sales. Would one therefore blame the respondent for delaying to sell the mortgaged property under those circumstances and should 12 court sit to hear the main suit on that ground? I would say no because there is obviously no basis for the allegation. On the whole, even if this application had not been found to be incompetent I would have still been inclined to find no merit in it because all the alleged issues for trial are a mere sham. It does not raise any arguable case of illegality in the sale by the respondent and, or the charging of the contractual interest before and after the sale because loans continue to accrue the contractual interest until it is fully paid unless agreed otherwise by the parties. However, since I had already made a finding and conclusion on the point of law, this application stands struck out with costs for being incompetent and judgment as prayed for in the summary pliant is entered for the respondent/plaintiff. I so order. Dated this 5th day of February 2015. Hellen Obura JUDGE Ruling delivered in chambers at 3.30 pm in the presence of Mr.Stuart Ahebwa h/b for Mr. Patrick M. Mugisha for the applicant and Mr. Robert Okalang for the respondent. JUDGE 05/02/2015 13

![[2011] MR 3 - M. -v](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007645277_2-af39c45bb95d99b941f70f0acc872861-300x300.png)