U+I+P Strategic Partnerships

advertisement

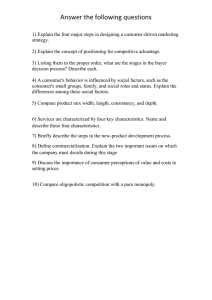

Accelerating Commercialization and Innovation: The U.S. Experience with the Triple Helix Richard A. Johnson KEFVIII – INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France 29 April – 1 May 2009 johnsri@alum.mit.edu Triple Helix: Accelerating Commercialization By Reinventing the Role of U + I + P: 5 U.S. Examples • Technology Transfer and the U.S. Bayh-Dole system • Shift to Industry-University-Government Collaborations and PublicPrivate Partnerships as the Emerging Model for Commercialization • National Laboratories and Government Departments as Commercialization Accelerators and Facilitators • Experimenting with a Diverse, Flexible and Changing “Toolkit” through Increased Entrepreneurship and State/Regional Initiatives • Viewing Commercialization and Technology Transfer as Integral Parts of a “Systems Framework” for Innovation in a KBE Bayh-Dole and U.S. Commercialization of Publiclyfunded R&D: 30 years of experience • Universities, Non-profits, SMEs obtain title to IPR developed with public funding by faculty, students or employees (IPR is not the goal of publiclyfunded R&D, just a by-product) • Universities/Public research labs/Non-profits must seek to commercialize research that results from publicly-funded R&D • Government receives royalty-free, non-exclusive license for procurement but no right to government pricing control over products/services from it • Government retains “march-in” rights if university/public lab/SME fails to adequately commercialize • Preference in licensing to SMEs • Royalties/payments must be shared with the inventor(s) and reinvested Transferring University and Public Research Organization Technology to Firms SALES $$ ROYALTIES or EQUITY PAYOUT UNIVERSITY SBIR NEW PRODUCTS & PROCESSES License Agreement or Equity RESEARCH $$ • • • COMMERCIAL COMPANY INNOVATION INVESTMENT $$ Licensing to existing companies – brings royalty $ New company formation – brings royalties and/or equity Other, less direct, contributions to regional economic Drawn from C. Gabriel, Carnegie Mellon University activity 7 U.S. Technology Transfer in Operation • Each university/public laboratory establishes its own policies, royalty-sharing, and governance system – TTO deducts ≈ 15-20% for overhead and costs (►net royalty) – Common allocation (Stanford, U. of Washington) – create incentives among all key stakeholders: • 1/3 inventor(s) • 1/3 academic department or lab at public research centers • 1/3 School and/or University general funds – Scaled allocations depending on size of payments (Harvard, Brown, many state universities – public): inventor receives greater % for smaller amounts • General rule: All research must be publishable • Increasing trend to equity-sharing deals for start-ups • Department/University/Labs must reinvest returns Promoting Commercialization Benefits for Faculty and Researchers – It’s Not Just about the Money • Financial – important incentive but often not the key reason – Additional personal income – Research funding to PI’s lab or center – Paid consulting arrangements with licensee or start-up (consistent with strict university policies on Conflict of Interests and Conflict of Commitment) – Service on Scientific Advisory Board of start-up companies • Career and prestige – faculty/PIs want innovation/commercialization – Enhances and improves quality of investigators’ Fundamental Research (asks new questions; provides new feedback; ensures rigor and quality) – Key selling point for attracting and retaining best academic/research talent – Considered for tenure and advancement at some universities/labs – Access to additional Human Capital and talent beyond the university – Ability to leverage and use equipment, tools, and cutting-edge infrastructure – Successful Serial Entrepreneurs have high prestige in their field and with public (Examples – John Hennessy (Stanford President); John Donahue (Brown neuroscientist); Phil Sharp (MIT Nobel Laureate – Biogen and Alnylam); Robert Langer (pre-eminent MIT chemist and engineer, created >60 successful companies); The Entrepreneurial University and Technology Transfer Enables Excellence in Core Academic Missions – Research, Education and Public Service • Universities as Engines of Economic Growth and Hub of 21st Century Knowledge-based Economy (Research, Education, Public Service) – Google, Genentech, Cisco and thousands of sustainable SMEs – Entrepreneurs and SMEs drive the U.S. economy and job creation – 27 universities >$10 million/year in gross income from licensing and fees; >200 American universities active in U+I tech transfer – >$42 billion/year in new economic activity in United States – Invention disclosures = 19,827; 3,622 new university patents (2007) – 555 new start-up companies from universities in 2007 – 686 new products introduced to markets in 2007 (5,036 in 10 yrs.) – 12,000 + licenses and options producing income Slide 10 – Significant new job creation with higher wages Some American Triple Helix Commercialization Results • 550,000 small businesses created 1996-2004 • 17% of GDP and 9% of jobs came from venture capital-back startups, most of which originated in universities or with public R&D • IPR and university/national lab revenues are not the primary goal – it is not about the money; it’s about driving new interactions, insights, collaborations and solutions that accelerate commercialization across the knowledge supply chain and entrepreneurial ecosystem • “People don’t buy technology, they buy solutions” (Lita Nelsen, MIT) • It’s much more than just S&T, R&D inputs, patents and publications, and it is not a linear process MIT May Be Sui Generis, BUT It Shows What an Entrepreneurial University and Ecosystem Can Achieve • Commercialization from the MIT entrepreneurial ecosystem = the 11th largest economy in the world • MIT- related companies globally = 25,800 • Job creation = 3.3 million jobs around the world • Global world sales from MIT companies = $2 trillion/year • New company formation from the next generation MIT entrepreneurial environment is accelerating > 5,600 new companies in United States since 2000 • Huge regional and local impacts – not just economic, and many outside the United States 6 New Tech Transfer Trends in the United States • Universities increasingly viewed as key parts and leaders of complex Entrepreneurial Ecosystems • Promote Access and Diffusion – e.g., license IPR more creatively to spur innovation and meet social needs: 9 core principles now guide licensing to balance public and private needs • No longer just S&T, biomedicine and engineering -- Design and New Media -- Knowledge-intensive services • Focus on collaborative research and broader/deeper partnerships • Social Innovation and Relational Nets are key, new aspects for commercialization of public R&D – focus on relationships, organizations, interactions and trust; align with social networking • Globalization of the American universities and international universities creates new challenges and opportunities for accelerating commercialization: new global networks/linkages Government Departments Have Increased Propensity to Commercialize Their Research – e.g., National Institutes of Health (NIH) • Largest publicly-funded R&D to advance public health; Budget ≈ US$27 billion; 27 Institutes, Centers and Divisions: 60,000 awards/yr; 18,000 employees; active Office of Technology Transfer • NIH views commercialization as key to promoting public health • Robust NIH pipeline and >2,500 patents • Novel, fundamental research discoveries and inventions • “Supermarket” for research tools and materials in biomedicine • >2,000 active licenses with product sales > US$3 billion/year • NIH researcher/inventors also get royalties – capped at $150K/year (30 researchers at NIH are at annual cap) • NIH has commercialized more than 250 biomedical technologies • Social capital (broad interactions and collaborations) increases the likelihood that NIH researchers will commercialize their research Increased Industry Role for Commercializing Public R&D – The 3 R’s (IBM) for Creating Mutual Value and Accelerating Innovation • Reach and Modes of Engagement – Skills development and support for educational infrastructures – Lifelong learning, retraining and courseware development – Virtual, face-to-face, peer-to-peer, partnerships • Research (Discovery-driven and Solutions-driven) – Increased focus on Innovation and leveraging public R&D – Collaboratories and sustained partnerships (bi- and multidirectional among U+I+P); deep exchanges and mobility – Access to and sharing of equipment, tools and infrastructure • Recruiting and Human Capital – Top talent for the future – Internships, co-ops, post-docs, team based project challenges U+I+P Strategic Partnerships – “No One Size Fits All” • Sponsored Research and “windows into research” • Increased trend toward “Collaboratories” and other longer-term, multi-directional partnerships • “User-driven Innovation” and distributed R&D networks create new commercialization opportunities • Integrating entrepreneurial ecosystems and investments • Public-private partnerships for addressing societal issues • Social Entrepreneurship and Venture Philanthropy • Pre-competitive consortia (National Institutes of Health -GAIN, TCGA, SNPs, HapMap) and shared infrastructure • Location-specific competencies: the role of clusters/hubs U.S. National Laboratories: A New Role as Commercialization Accelerators • • • • • • • Major shift toward commercialization in last 10 years Technology-based economic development at all levels Wide use of CRADAs and de-centralized collaborations Affiliated incubators and S&T research parks Technical assistance and brokering services for SMEs Mentoring, educational outreach and career metrics Leveraging expensive government-funded research equipment and tools; shared access and services • Small Business Assistance programs: 650 at Sandia Lab • Sponsor venture capital forums and link to capital flows • Commercialization Incentives – financial and personnel The Current U.S. Toolkit for Accelerating Commercialization is Marked by its Diversity • Incentives, not mandates: flexible and market-oriented • Innovation awards for start-ups and SMEs – the SBIR program and others • Entrepreneurial ecosystems – universities, regions, national labs, 50 American states, and industry clusters • Incubators, research parks and clusters (some virtual) • Entrepreneurship best practices, competitions, mentors • Champions, meritocratic and sustainable funding • Pre-competitive public-private consortia • Public-private partnerships for societal grand challenges $143 billion TheSocial SBIR “Open Innovation” Model and Government Needs Private Sector Investment PHASE II Research towards Prototype PHASE I Feasibility Research $100K PHASE III Product Development for Gov’t or Commercial Market Non-SBIR Government Investment $750K Tax Revenue Federal Investment © Charles W. Wessner 22 Some Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Accelerating Commercialization from Public R&D that Are Overlooked • Key Role of “Soft Infrastructure”, Intermediaries and Risk Investors • Commercialization Critical to Basic Research and University Role • Supportive Entrepreneurial Climate and Policies – Technology Seeds Must Land on Fertile Fields – Failure is Tolerated (and Celebrated) and Risk Taking viewed as a “positive” • Immigration as a Source of Talent and Drive – 35-40% of U.S. startups and entrepreneurial activity in last 25 years came from persons not born in the United States • Vigorous Domestic Competition and 50 States Funding (not federal) – the competition for economic activity, jobs and investment among the 50 U.S. states is intense (regions, clusters) and accelerates commercialization and innovative activity with publicly-funded R&D • Increasing Focus on Whole-of-Government Framework Conditions – Tax Policy, Labor Mobility, Competition, Human Capital, Innovation An Emerging New Toolkit for Accelerating Commercialization in SMEs at Global Scale • Focus on Knowledge Markets and Intellectual Assets • Virtual technology accelerators (plus physical incubators) • On-line matchmaking and social/business networking tools for SMEs and national innovation infrastructures • Linking global “brain circulation” strategies with global and regional commercialization and clusters • Harvestable Innovation – a new approach • Open Innovation collaborative mechanisms to overcome the limitations of size, geography, and global “bandwidth” • The hub of U.S. initiatives is at the local, regional and state level (“bottom up” driven with “top down” support) The Innovation Framework Slide 25

![Introduction [max 1 pg]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007168054_1-d63441680c3a2b0b41ae7f89ed2aefb8-300x300.png)