Understanding the impact of urban green space quality on health

advertisement

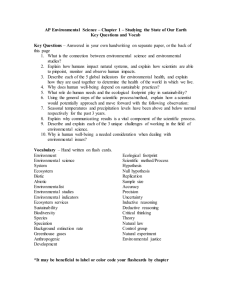

Quality of public space, well-being and health in BME communities Dr Edward Hobson Head of research and futures The government’s advisor on architecture, urban design and public space 2 In outline An age old problem of resource distribution Contemporary drivers require a joined up response Understanding similarity and difference 3 Patterns2 4 Patterns3 5 Patterns4 6 Patterns 7 8 9 ‘We face a major economic crisis and we face a still bigger climate crisis and by thinking through clearly and carefully, and acting quickly, we can respond to both of them at the same time. Lord Stern, January 2009 10 Climate change: the biggest global health threat of the 21st century “Managing the health effects of climate change” Lancet/UCL Commission (16 May 2009) Key areas of impact – patterns of disease and mortality – food security – water and sanitation – shelter and human settlements – extreme events – population migration 11 What’s good for people’s health is good for the planet too “We must develop win–win situations whereby we mitigate and adapt to climate change and at the same time significantly improve human health and wellbeing. There are major health benefits from low-carbon lifestyles, which can reduce obesity, heart and lung disease, diabetes and stress.” Professor Anthony Costello (UCL Institute for Global Health) 12 Moderating extreme temperatures High density residential Max surface temp (°C) 40 35 current form 30 -10% green 25 +10% green 20 15 1970s 2020s Low 2020s High 2050s Low 2050s High 2080s Low 2080s High Time period and scenario Adaptation Strategies for Climate Change in Urban Environments (ASCCUE), University of Manchester 13 Heatwave impact on London The Urban Heat Island Effect 14 15 16 Persistent incidences of deprivation Lindsay, 2008 17 Health, well-being climate change Different parts of the UK will be affected in different ways and the social impacts may well be more pronounced in more economically vulnerable areas. Disproportionate effect on the vulnerable in society – the elderly, the poor, those with less choice to avoid poorer quality internal and external environments. Particularly severe direct impacts include – – – – Urban heat island effect – overheating Fuel and energy insecurity Surface water flooding Reduced air quality A report by the Roundtable on Climate Change and Poverty in the UK emphasises the interconnectedness between climate change and poverty – and that it is possible to tackle both together. 18 Links between quality of public space, health and well-being Value for exercise unquestionable MIND ‘Ecotherapy’ should be recognised as a clinically valid treatment for mental distress (2007) 74% of people believe parks and open spaces are important to people’s health and well being 19 Proving the links between quality of public space, well-being and health Overall, research presents a clear positive relationship between green space, well-being and health. BUT: evidence base as a whole is highly variable - Self-reported data limiting value - Findings can’t support cause and effect, correlations only - Limited use of objective measurements in physical exercise studies - Findings not transferable outside specific study context (Source: Greenspace Scotland commissioned critical literature reviews 2007,2008) 20 Other relevant work? Building Health: Creating and Enhancing Places for Healthy, Active Lives: What needs to be done? Future Health (provisional title) Making the links between health, well being and sustainability 21 Making green spaces deliver more Importance of a strategic approach - green infrastructure for environmental and social benefits Do we have the information to support this approach? 22 Making the most of existing data and developing the evidence base Initial scoping study ‘Green and Pleasant’ research: 1. Creating a baseline of evidence of the current state of England’s urban green space 2. Mapping and understanding the links between deprivation, race and ethnicity and quality of urban green space 23 The ‘state’ of England’s urban green spaces Inventory of over 17,000 spaces in 154 urban local authorities Indicators around 6 themes: quantity, quality, use, accessibility, management and maintenance and value 14 core indicators as a baseline for future trends Data gaps and limitations 24 Some of the barriers to defining the country’s urban green spaces No single, national indicator or dataset on quality Cleanliness or maintenance information only No dataset of quantity Deciding specific bundles of characteristics Combination of objective and subjective indicators Difficult to isolate the impacts Measurability and data availability driving definitions of quality of life and quality of public space 25 Barriers continued…. Acute lack of skills e.g. 68% said a lack of horticulture skills is affecting service delivery Shortage of professionals such as landscape architects and green space managers Collecting data is like eating your greens! Shortage of directly applicable National Indicators 26 Features of public space not measured in national datasets Type of feature of quality of public space Feature Condition/maintenance Robust, Adaptable Design Well-designed, Legible Has sense of enclosure User Healthy Space for social interaction Fulfilling, Relaxing Function Community resource Vital and viable, Functional Source: CABE scoping study into the links between quality of public space and quality of life 27 Aspirations for public space 1. Clean: a clean and well cared-for place 2. Accessible: a place that is easy to get to and move through 3. Attractive: a visually pleasing place 4. Comfortable: somewhere that is pleasant to spend time in 5. Inclusive: a place that is welcoming to all 6. Vital and viable: a place that is well used in relation to its predominant function(s) 7. Functional: a place that functions well at all times 8. Distinctive: somewhere that makes the most of its character 9. Safe and secure: somewhere that feels safe from harm 10 Robust: a place that stands up well to the pressures of everyday use 28 Moving beyond the urban centres - where the quality dips [picture of a nice central park] What of the areas that don’t feature on the glossies 29 30 31 A question of equity How is quality of urban green space important and significant to health and well-being in people from white British and black and minority ethnic groups living in deprived areas of England? What is the impact of varying quality in urban green space on well-being in these areas? What are the implications of these findings for policy makers? 32 Author Method Target group Rishbeth, in press[1] QUAL (audio methodologies) First generation migrants, Sheffield, and use of urban streetscape, n=11 Dines et al 2006[2] QUAL (focus groups) n=42, ethnographic analysis, semistructured interviews (n=24) Newham (cross-section of the local residential population in terms of ethnicity, age, gender and housing tenure) Rishbeth 2004[3], 2001[4] QUAL+QUAN (2 year, mixed methods, n=73) Users of Chumleigh Gardens (Southwark), Calthorpe Project (King’s Cross) white British and Asian/Africans Topia-Kelly 2004[5] QUAL Biographies, n=22 Asian women Ravenscroft and Markwell 2000[6] QUAL Interviews of park users, (n=294) plus observation Teenage users of 8 parks in Reading Woolley and Amin 1999[7] QAUL+QUAN Focus groups, questionnaire (n=117) Pakistani teenagers, age 13-18,Sheffield Worpole and Greenhalgh 1995[8] QUAL+QUAN surveys, interviews, observation, 12 LA’s Ethnic park users in Middlesbrough, Hounslow, Greenwich and Leicester 33 Selecting areas to explore these relationships 6 case study areas in England: London, West Midlands and North West On the ground audits of green space Facilitated face to face household questionnaire and focus groups Largest survey of its kind in UK 34 Tiers of analysis Environmental audits of local green spaces Community group and independent evaluators Site visits and appraisals Survey approaches Conjoint analysis of urban green space relative to other environmental attributes Exploring relations across self-perceptions of well-being, perceived quality and use of local green space 35 Issues for consideration Whether there are convergent similarities or significant differences between ethnic groups? Whether our assumptions hold for what is significant and important to particular communities? How this might affect the need and provision for certain types of green space and the implications for more responsive management. 36 Equates to… Sustainable design Well being and happiness Healthy design Inclusive design 37 East London Green Grid 38 39 Thank you ehobson@cabe.org.uk cabe.org.uk sustainablecities.org.uk