Maude et al_ZTT - 2006 (1) - FPG Child Development Institute

advertisement

----EDUCATING AND

TRAIN ING STUDENTS TO

WORK WITH CULTURALLY,

LINGUISTICALLY, AND

ABILITY-DIVERSE YOUNG

CHILDREN AND THEIR

FAMILIES

f

- --

SUSAN P. MAUDE, University of Vermont

CAMILLE CATLETT, University of North Carolina, Chapel HW

SUSAN M. MOORE, University of Colorado , Boulder

SYLVIA Y. SANCHEZ, George M ason University

EVA K.THORP, George M ason University

ationwide, the demographics of young

children in the U.S. are changing dramatically. Reports from the Census

Bureau indicate that individuals from

non-European racially and ethnically

diverse backgrounds now comprise one

third of the U.S. population. Projections indicate that by

2030, 40% of the U.S. population will represent diverse

racial and ethnic groups (Goode, 2001). Children and

families in the U.S. today are also linguistically diverse.

Roughly 1 of every 10 children enrolled in public school

(pre-kindergarten through grade twelve) is an English Language Learner (ELL), with the most significant percentages

clustered 1 in ever-increasing numbers, in the youngest age

abstract

The quality of services for our increasing Iv diverse

families with infants and toddlers depends upon the

comfort, confidence, and competence of the personnel

available to provide these services. Colleges and universities must be able to produce graduates who possess the necessary sensitivity, knowledge, and skills to

serve children and families of diverse backgrounds

competently. The authors of this article describe four

universities’ approaches to educating students in teacher

preparation programs to deliver culturally and

linguistically responsive services.

ZERO TO THREE

Januaiy 2006

rtm

groups (Kindler, 2002). Most teachers and service providers

are working with or soon will be working with children and

families who are culturally and linguistically diverse.

The quality of services for our increasingly diverse families with infants and toddlers depends upon the comfort,

confidence, and competence of the personnel available to

provide these services. It is imperative for colleges and universities to produce graduates who possess the necessary

sensitivity, knowledge, and skills to serve children and

families of diverse backgrounds competently. Yet recent

research confirms that our workforce is not well-prepared

to support children and families who are culturally and

linguistically diverse. For example, many graduates are illprepared to respond to diverse family child-rearing preferences, support the development of young English language

learners, or collaborate confidently with diverse families

(Goor & Porter, 1999). In fact, in a national survey of

teachers, the majority indicated that they prefer and feel

most comfortable working with children from their own

culture (Evans, Torrey, & Newton, 1997). Further compounding the problem is evidence that colleges and universities have not been successful in recruiting, supporting 1 and

preparing students who reflect the diversity of the children and families they serve (Isenberg, 2001; Kushner &

Ortiz, 2001). Moreover, institutions of higher education

face growing shortages of faculty in general, especially in

special education, allied health, and related fields (Smith,

Pion, Tyler, Sindelar, & Rosenberg, 2001).

Colleges and universities must pay attention to what

faculty members teach, how they teach, and where students

learn and from whom, in ways that are consistent with

state standards and national accreditation requirements.

Faculty need support to address these dimensions directly

through program practices (e.g., how students are

recruited, how faculty are hired, policies on and supports

for diversity), coursework, and field experiences (Burant,

Quiocho, & Rios, 2002; Ligons, Rosado, & Houston, 1998).

This article describes four university programs that have

used different approaches to addressing the challenge of

educating and training students to work with culturally and

linguistically diverse families.

nel preparatio11. The first motivation was the increasing

evidence that early care and education professionals need

to be prepared to work with children with varying abilities

and from varying cultural communities in inclusive settings

(Miller & Stayton, 1998, 2003 ). Program developers also

recognized the increasing diversity of the children and families in the community and the fact that few early care professionals were prepared to work with families from diverse

cultural and linguistic communities. Moreover, most had

few personal experiences with individuals from communities other than their own.

The UTEEM program is field-based, offering students

four internship experiences in community and school pro

giams serving diverse learners, while they are simultaneously enrolled in university courses. These courses are

organized in blocks that correspond to age or developmental stage, so that students are able to engage in intensive

study of children and families at a child's particular age.

For example, there is an infant-toddler block of courses, a

preschool block, and a block that focuses on children from

kindergarten to grade three. A fourth block of courses

address foundational issues such as the use of action

research (a focused effort of inquiry to improve the quality

of services and supports), curricular integration of

adaptive and assistive technology, policy issues affecting

Diverse young learners, and pedagogical and philosophical

foundations framing work with diverse young learners and

their families. In these courses, students explore historical

and socio-cultural factors that have contributed to the

Unified Transformative Early

Education Mode.I (UTEEM)-Virginia

The Unified Transformative Early Education Model

(UTEEM) Early Childhood Program at George Mason

University prepares teachers to ·work with culturally, linguistically, and ability-diverse young children, from birth

to grade three, and their families. Graduates of the program

receive Virginia licensure in Early Childhood Education,

(pre-k to grade three); Early Childhood Special Education,

(birth to age 5); and English as a Second Language Education (pre-k to grade 12).

The UTEEM program was explicitly designed to

respond to current trends and needs in the field of person-

ZERO TO THREE

January 2006

m

marginalization of diverse populations in school and comdiversity and disability should be considered outside of or

munity settings. They also analyze classic and current

in addition to other aspects of child development and famreadings that can build the capacity of teachers to feel

ily functioning. The UTEEM program is structured to

comfortable, competent, and confident in creating enviincorporate issues of linguistic diversity, multiculturalism,

ronments that welcome diverse young children and their

and disability in every class. This conscious decision was

families.

made early in program design after a faculty review of cur·

Several key features of the UTEEM program, described

rent college texts confirmed that 1nost resources address

in detail below, ensure the infusion of diversity throughout

special populations or issues of diversity as separate chap.

ters, as if these were not issues

the program and lend themselves

r-------- '-------- related to all children.

to replication by other preservice

programs. These include: (a) an

An integrated faculty planning

The primary philosophical principle

process

enables faculty to revisit

integrated philosophy and guiding

that undergirds the UTEEM

principles, (b) an integrated prothe

guiding

principles each semesprogram is that culture is the

gram structure that weaves issues of

ter

and

to

discuss

how course con

lens through which all experiences

diversity into all aspects of the curtent

will

ensure

that

students have

are viewed and interpreted

riculum; (c) a systematic faculty

opportunities to explore their own

planning process which provides

cultural lens. Learning activities

regular opportunities to reassess the program, and (d) a set

and readings are carefully selected to increase students'

of teaching routines and strategies to ensure that issues of

capacity to better understand the experience of families in

diversity are explicitly addressed.

diverse cultural communities and families of children with

The importance of philosophy-based teacher preparadisabilities.

tion is well established in the early intervention literature

Finally, faculty plan a variety of instructional routines,

assignments, and strategies to support the integrated philos(McCollum & Catlett, 1997; McCollum, Rowan, &

ophy. Among these is the use of a strategy termed "cultural

Thorp, 1994; Miller & Stayton, 2003). The architects of

dilemmas." On a monthly basis, students write about dilemthe UTEEM program realized the importance of an intemas they are experiencing in their field experiences. A sysgrative philosophy that includes diversity in all aspects of

tematic problem-solving process (e.g., stating the problem,

the curriculum and not as a separate course or lesson. This

refining the problem through fact finding, brainstorming

approach helps learners to engage in the challenging process

possible solutions, screening possible solutions, selecting an

of addressing issues of work with diverse learners in varied

action, and developing a plan) is used to help them explore

cultural communities. (n.b.: These guiding principles may

their cultural lens and to identify culturally appropriate

be reviewed in Miller, Ostrosky, Laumann, Thorp, Sanchez,

approaches to addressing the posed dilemma (Sanchez &

& Fader-Dunne, 2003, p. 125-137.)

Thorp, 1998; Thorp & Sanchez, 1998). Another key assignPerhaps the primary philosophical principle that under·

1nent in the program is to collect information to tell a family

girds the program is that culture is the lens through which

story about a family from a culture different from the

all experiences are viewed and interpreted. This single

students' own. This assignment 1 completed during the time

principle, while obvious in some respects, is also the most

students are learning about infants and toddlers, provides a

challenging and the most promising. It is not unusual for

powerful learning opportunity, a time to truly understand

students to feel that others belong to a culture and that they

family concerns, priorities 1 and decisions, and a time to betdo not, that culture is somehow sometl1h1g exotic. When

ter understand one's own cultural biases and assumptions

faculty make sure that they make reference to the cultural

(Kidd et al., 2004; Sanchez, 1999).

lens principle in each and every class, students begin to see

The impact of UTEEM's model for equipping students

that they do, indeed, belong to a culture. This realization

to enter the field with experience in reflective practice has

helps them to explore the ways in which their own culture,

been evaluated. Current research has found changes in the

while previously invisible to them, has framed all of their

students, including increased comfort in working with fam.assumptions, including those about early care and

ilies in diverse communities, increased awareness of the

education, cl1ild.-rearing routines, child care, family

impact of disability on a family, and increased ability to

dynamics, the use of home language, and so forth. By

understand family decisions. Students are 1nore competent

assisting students in acknowledging their cultural lens, fac·

to develop and integrate culturally responsive and relevant

ulty can create opportunities for students to explore their

curricula as they work with and support culturally, linguisviews of family decisions and practices, design culturally

tically, and ability-diverse children and their families.

relevant environments for children, and engage in cultur.ally appropriate interactions with families (Kidd, Sanchez,

Project ACT-Colorado

& Thorp, 2004; Sanchez, 1999; Thorp, 1997).

Project ACT is a second example of an effective

A second feature, the integrated program structure,

approach

to personnel preparation. Implemented at the

serves to challenge students' perceptions that issues of

- ------r--------'-

ZERO TO THREE

]anua1y 2006

Bl:J

University of Colorado, Boulder (UCB) and University of

ilies. Some of the accomplishments of Project ACT

Colorado, Denver (UCD) over the past 10 years, Project

include:

ACT uses "cultural mediators," who may also be well

• Infusing diversity within coursework and practica at

trained interpreters and translators, to better prepare stuthe preservice level in speech and language pathology

dents and early childhood professionals to work with chilgraduate programs at UCB and in early childhood spedren and families who are from backgrounds that are

cial education at UCD through guest lectures, culculturally and linguistically different from their own.

tural mediator round tables, and panel presentations.

"Cultural mediator" is a term derived from culture,

•

Partnerships with local school districts that serve

language mediator (Barrera, 1993;

many children and families

Barrera, Corso, & MacPherson 1

from

diverse linguistic and

2003) and is defined as "a commuSchool districts and early

cultural backgrounds. For

nity person, familiar with various

intervention systems throughout

example, students participate

ethnic neighborhoods, who spent

the state use cultural mediators

each semester with the Child

time with families, getting

to help service providers reach

Find bilingual team in Boulder

acquainted with them and

out to children and families.

Valley School District, serving

acquainting them to special educamonolingual Spanishtion service delivery" (Barrera,

speaking

families

with

children

ages birth to 5.

1993, p.470). In Colorado, the definition of cultural medi•

Community

collaborations,

such

as

El Grupo de Familias,

ator has evolved to describe the role of an individual who

a

parent

education

and

support

group

developed by

helps translate between the culture of the professional

Project

ACT

for

monolingual

Spanish-speaking

environment and the child's family, in order to enhance

families, financially supported by the local early interunderstanding, share information, and create relationships

vention

system (Part C of IDEA) Kids Connection

that support families' full participation in their child's care

and

the

Boulder

City Human Services Fund. Each

and education (Moore, Beatty & Perez-Mendez, 1995,

semester

students

participate in this practicum 1 which

2001). Additional terms for individuals in this role include

focuses

on

early

intervention,

preservation of home

cultural broker (National Center for Cultural Competence,

language

and

culture,

language

and literacy activities

2004) parent-school liaison or parent resource consultant.

for

family

members,

and

navigation

of community

Regardless of the title, this individual is a valued mem·

resources

and

supports,

such'

as

the

public

library and

ber of a child and families' community and understands

the

school

district.

both community and professional cultures. She is profi• Ongoing collaborations with the Peak Parent Center,

cient in English as well as the preferred language(s) used by

Colorado's parent training and information center.

a family; accepted by the family; willing to take direction;

For example, Project ACT and Peak have sponsored

flexible within her role; and able to maintain strict confian annual conference, Continuing the Circle, to

dentiality ( Moore, Perez-Mendez, Beatty & Eiserman,

explore culture and related topics. The conference

1995). In Colorado, experienced family members, other

draws family members of children with diverse abilikey community members, and bilingual support personnel

ties, community providers, and students in personnel

have been trained to be cultural mediators. Currently,

preparation programs.

these individuals ate able to receive additional training

through a statewide initiative, funded through the Col·

Working with cultural mediators and parent resource

orado Department of Education, to expand their role

consultants through Project ACT has taught students to:

beyond interpreter and/or translator in special education.

School districts and early intervention systems through• Listen to and value family perspectives;

out the state use cultural mediators to help service

• Move beyond stereotypes toward individual considproviders reach out to children and families: In Colorado,

eration of each child and family within their socioindividuals and families who need early intervention ser·

cultural context;

vices speak many different languages, including Spanish,

• Connect and develop relationships with children and

Hmong, Chinese, and Russian. Some families, with Ameri..families who come from cultures, or speak languages

can Indian and African- American heritage, have been disdifferent from their own, or both;

enfranchised. Support from cultural mediators provides

• Understand how cultural and linguistic differences

professionals and students in personnel preparation pro.can influence how families experience or participate

grams opportunities to: learn about cultural beliefs and life

in their child's early care and education and/or interways different from their own; recognize bias and how it

vention;

can become a barrier to effective assessment; support chil• Discover ways to support and preserve home language

dren and families with linguistic and cultural differences;

and culture within the context of early care and edubuild reciprocal relationships of trust and respect with famcation; and

ZERO TO THREE

January 2006

m

• Recognize that over, and under-representation of certain populations in special education may be caused,

in part, by biased assess1nent practices.

Educators Without Borders (EWB)Virginia

A third model of personnel preparation, Educators

Without Borders, infuses issues of culture and diversity into

all aspects of an instructional program that is designed to

recruit culturally and linguistically diverse students as future

educators. Educators Without Borders is a federallyfunded

project located at George Mason University in Vir ginia.

This program is designed to increase the representa tion of

culturally and linguistically diverse individuals in the field of

early childhood special education while implementing

effective strategies to maintain and sustain interns from

diverse backgrounds who are preparing to beco1ne

educational professionals. The program has not only had

an impact on the culturally, linguistically, and abilitydiverse interns, but, equally significant, has influenced the

quality of training for all students enrolled in the university's teacher preparation programs. Three strategies used

in this project have proved to be effective in supporting the

development of future educators:

PHOTO: MARILYN NOLT

emotional needs of diverse interns. For example) we have a

partnership with the campus chapter of the National

Coalition Building Institute (NCBI), an international

organization dedicated to reducing prejudice and developing coalitions across groups. Recruiting 1nembers of under,

represented populations into the teaching profession

requires helping future educators learn to address the

racism and prejudice that characterize many early care and

education settings.

A third strategy for personnel preparation involves

enhancing the leadership and advocacy skills of early educators from diverse backgrounds. Monthly leadership seminars address dilemmas that the interns face in their work. The

interns also participate in a train- the-trainer NCBI

workshop, after which they use what they have learned to

train their peers. Assuming leadership roles among their

peers has been essential to the development of these future

educators. Because many of the interns from diverse and

disenfranchised com1nunities have been silenced in previous educational settings, they are accusto1ned to leaving

leadership to students from privileged backgrounds. All

early education personnel preparation should com1nit

themselves to breaking this pattern, for the sake of interns

from privileged backgrounds as well as those from disenfranchised communities.

The EWB project's strategies can be implemented in any

personnel preparation program that is co11cemed about

the lack of diversity among education professionals. A commitment to change in the field requires active recruitment of

students from diverse cultural and racial backgrounds. In

addition, faculty must commit themselves to designing pro,

Sharing personal experiences related to one 1s own

culture,

• Building coalitions among university faculty to

increase cultural awareness and reduce prejudice, and

• Developing students' leadership and advocacy skills.

O

The first strategy is to create numerous opportunities

for interns to share their personal cultural lens. Future

educators can better understand the impact of race and

culture when they have the opportunity to hear and tell

personal stories. For example, the story of a bilingual

classmate who entered preschool as a non-English

speaking 3-year-old and vividly remembers the isolation

and confusion he felt can teach others about the impact

such experiences can have on family life and identity

development. Future educators who hear such stories are

helped to understand the challenges faced by young

children in linguistically diverse com1nunities.

The opportunity to share and honor personal family

stories is important for all program participants. The experience can be an impetus for deeper self-reflection, which

may require e1notional support. Personal stories 1nay be a

gift for others, but for the storyteller the telling may evoke

pain and debilitating frustration as she recounts experiences

of prejudice and discrimination.

Building coalitions, the second strategy used by EWB

faculty 1 involves working with allies across the university

who are also committed to addressing issues of race, culture, power) class, and privilege. Close collaboration

between EWB and other university faculty strengthens the

ability of the university’s infrastructure to support the socio-

ZERO TO THREE

Januaiy 2006

m

Figure 1 The Crosswalks Project vision

,.

grams that will allow the experiences, perceptions, and

skills of traditionally marginalized groups to surface and be

honored for the contribution they can make to the field in

general and to work with diverse children and families in

particular. Campuses that fulfill their commitment may

experience what the faculty at George Mason University

have discovered-these strategies are likely to benefit

teacher education preparation programs campus.-wide.

The Crosswalks Project-North

Carolina

What does it take to assist other universities and colleges as they embark on the journey toward culturally

responsive preservice programs? At the University of

North Carolina's Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, The Crosswalks Project is working to help

college and university programs systematically address

diversity. The Crosswalks Project recognizes that to pre,

pare students to work effectively with children and families

from other cultures, higher education faculty and administrators, working in concert with family members and community partners, need support in understanding the

meaning of cultural diversity and how to effectively integrate it into all facets of their preservice programs. Programs need to value diversity (Thorp & Sanchez, 1998)

and content (Ligons et al., 1998; Mora, 2000), using

instructional strategies (Guillaume, Zuniga-Hill, & Yee,

1998) that are consistent with culturally relevant practices.

These efforts must take place within the context of state

and national standards to which higher education programs must be responsive. Figure 1captures the vision of

The Crosswalks Project for braiding these four elements

together to create diversity-enhanced preservice programs.

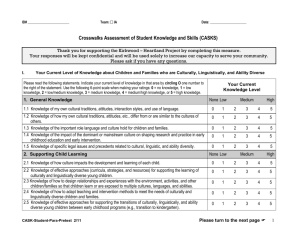

The Crosswalks Project is using two interrelated

approaches to offering culturally responsive preservice

training. The first approach involves a capacity-building

effort-a structured sequence of needs assessment, planning

training, technical assistance, and resources-to support

preservice programs in changing the extent to which

diversity is reflected in coursework, practica, and program

practices such as recruitment and mentoring. To assist in

this effort, five North Carolina institutions of higher education 1 are participating in The Crosswalks Project over a

24-month period. These campuses were selected after a

statewide recruitment and application process. Each site

has made a commitment to making changes in what they

teach, how they teach, where they teach, and with whom

they teach, to be responsive to and reflective of diversity.

It's important to note that each program is represented by a

team of Campus-Community Partners 1 which includes faculty, former students (graduates), family members,

practicum site directors, and other community members.

Two of the five institutions (experimental group) have

been working together to identify the strengths of their

program and to set priorities for increasing the emphasis on

diversity. They have described the knowledge, skills, capabilities, and qualities they want their future graduates to

possess. On the basis of the priorities for change, the

Campus-Community Partners at these sites are participating in a yearlong sequence of training and technical assistance, provided through face-to-face workshops and

conference calls. Sample topics have included:

• Deconstructing course syllabi to examine the ways in

which diversity is reflected and to reconstruct more

culturally responsive syllabi;

• Understanding and applying information about second language acquisition;

• Identifying diverse and nontraditional sites for

practicum and field experiences; and

• Building authentically collaborative relationships

with culturally and linguistically diverse families.

'North Carolina colleges and universities that offer Birth-throughKindergarten (B-K) teacher licensure were eligible to apply to participate

in The Crosswalks Project. All B-K programs offer blended preparation

(early childhood and early childhood special education), respond to the

same state standards, and are approved by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction.

ZERO TO THREE

January 2006

may help programs begin the process of cultural selfThe remaining three institutions (control group) have

reflection.

received no planning, training, or technical assistance from

The Crosswalks Project.

How will we know if the sequence of planning, trainCoursework

ing, technical assistance, and resources makes a difference?

• Does coursework provide students with opportunities

All participants (faculty, community partners, and students)

to increase their knowledge of their own culture and

will participate in the collection of data designed to enable

heritage?

project evaluators to ascertain the impact this systems,

• Does coursework provide opportunities to learn systematically and without

planning effort has had on particistereotyping about and from

pants' attitudes toward diversity

various cultural and linguistic

and their knowledge and skill with

"Cultural mediators" enhance

groups?

respect to diversity-related topics.

understanding, share information,

In addition, project participants will

• Does coursework provide

and create relationships that

learning opportunities and

be asked to reflect on the ways in

support f amilies' full participation

which they see diversity reflected

encourage dialogue and

in their child's care and education

in the coursework, pracreflection about the skills

needed to work with English

tica 1 and program practices of their

respective colleges. Project staff will compare results for the

Language Learners and to support home language

experimental and control sites to see how much of a differmaintenance?

ence The Crosswalks Project made.

• Does coursework engage students in activities in which

they learn how culture, ethnicity, language, socioAs a second approach to capacity building, The Crosswalks Project is developing a database of instructional

economic status, and other factors influence caregiving

practices and early childhood development?

resources for use by faculty, trainers, and other leadership

• Does coursework draw upon families and their stories

personnel. Users will be able to search the Crosswalks

as a resource to the instructional process?

"toolbox" by state and national standards (to discover

resources that address both content and diversity), by aspect

of diversity (e.g., linguistic diversity) and by type of

Practica

instructional resource (e.g., case studies, activities, syllabi).

• Do practica occur in a variety of home and commuThis unique resource is available at http://www.fpg.unc.

nity settings serving diverse young children and famiedu/-scpp/crosswalks/toolbox/.

lies (e.g., homes of participating families participating

in early childhood programs, Early Head Start/Head

Summary

Start, WIC programs, shelters for homeless families)?

The values, content, and instructional strategies pre• Do practica offer opportunities for students to interact

sented by these four models may be of assistance to training

directly with children and families who are culturally

programs that are concerned about and committed to

and linguistically diverse?

preparing well-qualified early childhood service providers.

• Do practica provide opportunities for students to

The strategies include:

collaborate with and learn from interpreters,

t

translators, and cultural mediators?

I. Expanding and enhancing the preparation of personnel to work with culturally, linguistically, and abilitydiverse children and their families (UTEEM);

2. Developing strategies and resources to negotiate and

bridge relationships across diverse cultures (Project

ACT);

3. Promoting increased representation of diverse front

line service providers and professionals in the com.munity of programs and practitioners that support

young children and their families (EWB); and

4. Developing a process for systems change in early

childhood personnel preparation programs, primarily

by focusing on the infusi6n of diversity across values,

content, instructional strategies, and practicum (The

Crosswalks Project).

Program Practices

• Does the training program have faculty and staff who

reflect the diversity of the students in the program as

well as the overall community?

• Do program faculty and staff consider issues of race,

privilege, power, and class, and how these issues

impact ethnic and linguistic minorities entering the

teaching of education field?

• Does the program have students who reflect the diversity of the overall community?

• Does the program create environments for learning in

which differences are acknowledged, celebrated, and

respected?

If we are to maximize positive outcomes for diverse

young children and their families, we must provide quality

How does a preservice program take the first step in

this process of reexamination? The following questions

ZERO TO THREE

Janua1y 2006

ED

D. Horm-Wingerd, M. Hyson, and N. Karp (Eds.), New teachers for

a new century: The future of early childhood professional preparation

preservice training, courses, practica, and dialogue that will

enable service providers to obtain the critical attitudes,

knowledge, and skills to do so.

(pp. 123-154). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Ligons, C. M., Rosado, L. A., & Houston, W. R. (1998}. Culturally literate teachers: Preparation for 21st century schools. In M. E. Dilworth

(Ed.}, Being responsive to cultural differences: How teachers learn

(pp. 129-142}. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

McCollum, J. A., & Catlett, C. ( 1997). Designing effective personnel

preparation for early intervention: Theoretical frameworks. In P. Winton, J. McCollum, & C. Catlett (Eds.), Reforming personnel pre paration

in early intervention {pp. 105-126}. Baltimore: Paul Brookes.

McCollum, J. A., Rowan, L. E., & Thorp, E. K. (1994). Philosophy as

fra1nework in early intervention personnel training. Journal for

Early Intervention, 18(2), 216-226.

Miller, P., Ostrosky, M., Laumann, B., Thorp, E., Sanchez, S., & FaderDunne, L. ( 2003). Quality field experiences underlying performance

mastery. In V. Stayton, P. Miller, L. Dinnebeil (Eds.} DfC personnel

Authors' Note:

For information about UTEEM, contact Eva Thorp:

703-993-2035, ethorp@gmu.edu

For information about cultural mediators, contact

Susan Moore: 303-492-5284, susan.moore@colorado.edu

For information about Educators Without Borders, contact Sylvia Sanchez: 703-993-2041, ssanche2@gmu.edu

For more information about The Crosswalks Project, contact

Camille Catlett: 919-966-6635, catlett@mail.fpg. unc.edu, or visit

the Web site http://www.fpg.unc.edu/-scpp/crosswalks/

preparation in early childhood special education: Implementing the DEC

recommended practices (pp. 113-138). Denver, CO: Sopris West.

Miller, P. S., & Stayton, V. D. (1998}. Blended interdisciplinary teacher

preparation in early education and intervention: A national study.

Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 49-58.

Miller, P. S., & Stayton, V. D. {i103}. Understanding and meeting the

challenges to implementation of recommended practices in personnel

preparation. In V. Stayton, P. Miller, L. Dinnebeil (Eds.) DEC per5on-

REFERENCES

Barrera, L (1993) Effective and appropriate instruction for all children:

The challenge of cultural/linguistic diversity and young children with

special needs, Topics in Early Childhood Education, 13{4}, 461-487.

Barrera, I., Corso 1 R. M., & MacPherson, D. (2003). Skilled dialogue:

Strategies for responding to cultural diversity in early childhood. Baltimore:

Paul Brookes.

Burant, T., Quiocho, A., & Rios, F (2002). Changing the face of teach

ing: Barriers and possibilities. Multicultural Perspectives, 4(2), 8-14.

Evans, E. D., Torrey, C. C., & Newton, S. D. (1997}. Multicultural

requirements in teacher certification: A national survey. Multicultural

Education, Spring.

Goode, T. (2001). Policy brief 4: Engaging communities to realize the vision

of one hundred percent access and zero health disparities: A culturally competent approach. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child

Development Center, National Center for Cultural Competence.

Goor, M. B., & Porter, M. (1999). Preparation of teachers and administrators for working effectively with .multicultural students. In F. E.

Obiakor, J. 0. Schwenn, & A. F. Rotatori (Eds.), Advances in special

education (pp. 183-204). Stamford, CT: JAI Press, Inc.

Guillaume, A., Zuniga-Hill, C., & Yee, I. (1998). Prospective teachers'

use of diversity issues in a case study analysis. Journal of Research and

Development in Education, 28(2), 69-78.

Isenberg, J. P. (2001). The state of the art in early childhood professional

preparation. In D. I:iorm-Wingerd, M. Hyson, & N. Karp (Eds.), New

nel pre paration in early childhood special education: Implementing the DEC

recommended practices (pp. 183-196). Denver, CO: Sopris West.

Moore, S. M., Beatty, J., & Perez Mendez, C. (1995}. Developing cul

cural competence in early childhood assessment. Boulder: University of

Colorado.

Moore, S. M., Beatty, J., & Perez-Mendez, C. (2001). Project ACT:

Assessment practices, cultural competence , and transition planning for

young children. Grant #3408, 10 cde, University of Colorado, Boulder.

http://www.co lorado .edu/slhs/ACT.

Moore, S. M., Pen;z,Mendez, C., Beatty, J., & Eiserman, W. (1995).

A three,way corilrersation: Effective use of cultural mediators, inter

preters , and translatars. Video prodllced by The Spectrum Project

#H024D60007 and Project ACT #3408-10. Denver, CO: Western

Media Products.

Mora, J. K. (2000}. Staying the course in times of change: Preparing

teachers for language minority education. Journal of Teacher Education,

51 , 345-357.

National Center for Cultural Competence. (2004). Bridging the cultural

divide in health care settings: The essential role of cultural broker program. Retrieved July 21, 2005, from http://gucchd.georgetown.edu/nccc/

Sanchez, S. {1999). Leaming from the stories of culturally and linguistica!ly diverse families and communities: A sociohistorical lens.

Remedial and Special Education, 20(6), 351-359.

Sanchez, S., & Thorp, E. K. (1998). Discovering meaning of continuity:

Implications for the infant/family field. Zero tO Three, 18(6), 1-6.

Smith, D., Pion, G., Tyler, N., Sindelar, P., & Rosenberg, M. (April,

2001}. The stud y of special education leadership personnel with particular

attention to the professoriate. Report submitted to the U.S. Depari:ment

of Education. Project Number: H920T970006-00A.

Thorp, E. K. ( 1997). Increasing opportunities for partnership with culturally and linguistically diverse families. Intervention in School and Clinic ,

32(5), 261-269.

Thorp, E. K., & Sanchez, S.Y. (1998}. The use of discontinuity in preparing early educators of culturally, linguistically, and ability diverse

young children and their families. Zero to Three, 18(6), 27-33.

teachers for a new century: The future of early childhood professional preparation (pp. 15-58). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Kidd, J. K., Sanchez, S.Y., & Thorp, E. K. (2004). lnnovative practices in

education-gathering family stories: Facilitating preservice teachers'

cultural awareness and responsiveness. Action in Teacher Education,

26( l), 64-74.

Kindler, A. L. (2002). Survey of the states' limited English proficient students

and available educational programs and services: 2000-2001 summary

report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of

English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement and Academic

Achievement for Limited English Proficient Students.

Kushner, M. I., & Ortiz, A. A. (2001). The preparation of early childhood education teachers to serve English language learners. In

ZERO TO THREE

January 2006

iii