Poems - TeacherWeb

advertisement

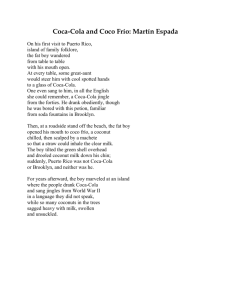

Elena My Spanish isn`t good enough I remember how I`d smile Listening my little ones Understanding every word they´d say, Their jokes, their songs, their plots Vamos a pedirle dulces a mama. Vamos. But that was in Mexico. Now my children go to American High Schools. They speak English. At night they sit around the Kitchen table, laugh with one another. I stand at the stove and feel dumb, alone. I bought a book to learn English. My husband frowned, drank more beer. My oldest said, 'Mama, he doesn´t want you to Be smarter than he is' I´m forty, Embarrased at mispronouncing words, Embarrased at the laughter of my children, The grocery, the mailman. Sometimes I take my English book and lock myself in the bathroom, say the thick words softly, for if I stop trying, I will be deaf when my children need my help. Pat Mora Jorge the Church Janitor Finally Quits Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989 No one asks is lost where I am from, when the guests complain I must be about toilet paper. from the country of janitors, I have always mopped this floor. What they say Honduras, you are a squatter's camp must be true: outside the city I am smart, of their understanding. but I have a bad attitude. No one can speak No one knows my name, that I quit tonight, I host the fiesta maybe the mop of the bathroom, will push on without me, stirring the toilet sniffing along the floor like a punchbowl. like a crazy squid The Spanish music of my name with stringy gray tentacles. They will call it Jorge. Martín Espada Heart of Hunger tobaccopicker, grapepicker, lettucepicker. Smuggled in boxcars through fields of dark morning, tied to bundles at railroad crossings, Obscured in the towering white clouds of cities in winter, the brown grain of faces dissolved in bus station dim, thousands are bowing to assembly lines, immigrants: mexicano, dominicano, frenzied in kitchens and sweatshops, guatemalteco, puertorriqueño, orphans and travelers, mopping the vomit of others' children, refused permission to use gas station toilets, and the steel mill glowing. leaning into the iron's steam beaten for a beer in unseen towns with white porches, Yet there is a pilgrimage, or evaporated without a tombstone in the peaceful grass, a history straining its arms and legs, a centipede of hands moving, an inexorable striving, hands clutching infants that grieve, shouting in Spanish fingers to the crucifix, at the police of city jails hands that labor. and border checkpoints, mexicano, dominicano, Long past backroads paved with solitude, guatemalteco, puertorriqueño, hands in the thousands reach for the cropground together, fishermen wading into the North American gloom the countless roots of a tree lightning-torn, to pull a fierce gasping life capillaries running to a heart of hunger, from the polluted current. Martín Espada Federico's Ghost Martín Espada and aiming for Federico, The story is leaving the skin beneath his shirt that whole families of fruitpickers wet and blistered, still crept between the furrows but still pumping his finger at the sky. of the field at dusk, when for reasons of whiskey or whatever After Federico died, the cropduster plane sprayed anyway, rumors at the labor camp floating a pesticide drizzle told of tomatoes picked and smashed at night, over the pickers growers muttering of vandal children who thrashed like dark birds or communists in camp, in a glistening white net, first threatening to call Immigration, except for Federico, then promising every Sunday off a skinny boy who stood apart if only the smashing of tomatoes would stop. in his own green row, and, knowing the pilot Still tomatoes were picked and squashed would not understand in Spanish in the dark, that he was the son of a whore, and the old women in camp instead jerked his arm said it was Federico, and thrust an obscene finger. laboring after sundown to cool the burns on his arms, The pilot understood. flinging tomatoes He circled the plane and sprayed again, at the cropduster watching a fine gauze of poison that hummed like a mosquito drift over the brown bodies lost in his ear, that cowered and scurried on the ground, and kept his soul awake. Blessed Be The Truth-Tellers For Jack Agüeros Jack who crossed his arms in a hunger strike until the mayor hired more Puerto Ricans. In the projects of Brooklyn, everyone lied. My mother used to say: And Jack said: If somebody starts a fight, You gonna get your tonsils out? just walk away. Ay bendito cuchifrito Puerto Rico. Then somebody would smack That’s gonna hurt. the back of my head and dance around me in a circle, laughing. I was etherized, then woke up on the ward When I was twelve, pus bubbled heaving black water onto white sheets. on my tonsils, and everyone said: A man poking through his hospital gown After the operation, you can have leaned over me and sneered: all the ice cream you want. You think you got it tough? Look at this! I bragged about the deal; and showed me the cauliflower tumor no longer would I chase the ice cream truck behind his ear. I heaved up black water again. down the street, panting at the bells to catch Johnny the ice cream man, The ice cream burned. who allegedly sold heroin the color of vanilla Vanilla was a snowball spiked with bits of glass. from the same window. My throat was red as a tunnel on fire after the head-on collision of two gasoline trucks. Then Jack the Truth-Teller visited the projects, Jack who herded real camels and sheep This is how I learned to trust through the snow of East Harlem every Three Kings’ Day, the poets and shepherds of East Harlem. Blessed be the Truth-Tellers, Jack who wrote sonnets of the jail cell for they shall have all the ice cream they want. and the racetrack and the boxing ring, Martín Espada Legal Alien Pat Mora Bi-lingual, Bi-cultural, able to slip from "How's life?" to "Me'stan volviendo loca," able to sit in a paneled office drafting memos in smooth English, able to order in fluent Spanish at a Mexican restaurant, American but hyphenated, viewed by Anglos as perhaps exotic, perhaps inferior, definitely different, viewed by Mexicans as alien, (their eyes say, "You may speak Spanish but you're not like me") an American to Mexicans a Mexican to Americans a handy token sliding back and forth between the fringes of both worlds by smiling by masking the discomfort of being pre-judged Bi-laterally.