AIDA WORLD CONGRESS (ROME 2014) ON LINE INSURANCE

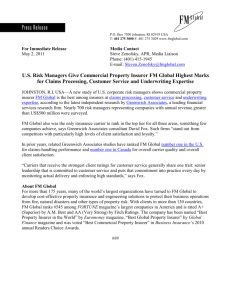

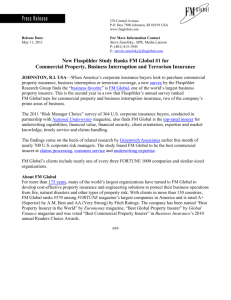

advertisement