Full Text (Final Version , 1mb)

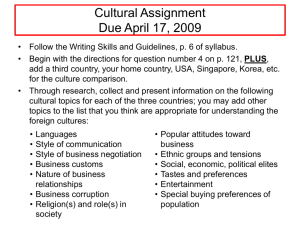

advertisement