Asset Securitization in the Aftermath of the Current Financial Crisis

advertisement

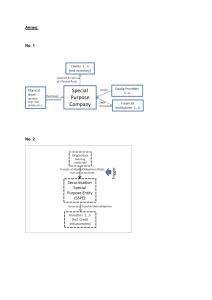

Asset Securitization in the Aftermath of the Current Financial Crisis: Lessons for Emerging Economies S.G. Badrinath Professor of Finance San Diego State University and S. Gubellini Assistant Professor of Finance San Diego State University First Draft May 2010 Please do not quote. 1 ABSTRACT This paper explores the implications of the current financial crisis for asset securitization activities. It begins with a brief review of securitization and how it enabled the management and transfer of interest-rate and credit risks. It documents the close relationship between securitization and various pieces of rule-making, FASB, Basel I and II, bankruptcy law, and derivatives regulation. It discusses the financial crisis from the perspective of the shadow banking system that emerged over the last few decades. Finally, it examines how the lessons learnt from the experience of developed economies can and should impact how emerging markets adopt securitization practices. 2 1. Introduction. The market for asset securitization has been dramatically affected by the financial crisis of the last few years. Media attention initially focused on plummeting housing prices and mortgage meltdown and is now focused on sweeping financial reform. Comprehensive reform is motivated largely by the inextricable links of asset securitization to different corners of the financial system. Securitization has historically provided favorable outcomes for many market participants. Sabry and Okongwi (2009) document that a 10 percent increase in securitization activity resulted in a decrease of between 4 and 64 basis points on yield spreads, depending on the specific type of the loan. Moreover, a 10 percent increase in secondary market purchases (of loans) increases mortgage loans per capita by 6.43 percent. This suggests that securitization provides individual borrowers with better access to credit and at cheaper terms. For investors, securitization structures offer a menu of choices from a diverse pool of mortgages and loans which are low in correlation so that in the event of a default, the senior tranches will continue to be paid out from the cash flows that are not lost in that default. Investors thus benefit from the ability to select from a menu of structured finance products that meet their desired level of risk tolerance and diversification. For banks and financial institutions that originate these loans, securitization provides a lower cost method of funding than the typical secured lending activity that they have historically engaged in. Gorton and Souleles (2005) argue that access to securitization markets also enables banks to reduce their bankruptcy costs. As recent events have demonstrated, these benefits have now resulted in large social costs as global central banks have accumulated large levels of debt in their bailouts of the Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and AIG- three players that are central to mortgage securitizations. From a welfare perspective, the ability of securitization to make loans appear less risky is a market imperfection and a cost-benefit analysis of securitization should form a part of any reform agenda in the developed world. Lessons learnt from the political economy of securitization also translate directly to emerging economies as they attempt to balance the benefits of securitization with its potential for systemic risk. 3 Accordingly, Section 2 of this paper begins with an overview of securitization and how financial institutions attempted to manage credit risk and interest rate risk. Section 3 discusses the emergence of a shadow banking system over many years of integration in financial markets culminating in the financial crisis and the global response to it. Section 4 provides a historical overview of various pieces of rule-making that continue to affect securitization. Section 5 provides an operational perspective on how emerging economics can adapt the lessons learnt in the West as they consider how securitization activities can improve their economic performance. 2. An overview of securitization. As is well known, securitization refers to the transformation of illiquid individual loans into securities. To provide a perspective on securitization, it is useful to viewing lending activity on a risk continuum. At one extreme is the traditional banking model where lenders originate the loan, service the loan and hold it till maturity. The loan is funded with deposits and the lender assumes both the credit risk of the borrower and the risk of changing interest rates. 1At the other end of this continuum is a 100% “originate and distribute” model where, instead of being concentrated, all the risk is distributed in the secondary market to investors. Lenders provide an intermediary function and have no incentive to monitor and manage loan quality as they merely pass the cash flows forward. Issues of asymmetric information and the possibility of adverse selection are not a concern since the investors take all that risk. Securitization lies in the middle of this conceptual continuum, with its exact location shrouded by the opacity surrounding lender risk retention, the complex series of off-balance transactions to shelter that risk and the lack of transparency in the over-the-counter markets where many of these deals are made. Securitization is commonly seen as a three-step process. First, originated loans are pooled together into mortgage-backed or asset-backed securities enabling a diversification of borrower risk. Second, these assets are transferred in a true-sale to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) so that 1 The maturity mis-match caused by borrowing short (via deposits) and lending long (to 30-year fixed rate mortgages) contributed to the Savings and Loans crisis of the 1980s. 4 the cash flows from these assets cannot be attached in the event of originator bankruptcy.2 Third, the SPV issues different tranches or slices of bonds where the cash flow is passed through from the original collateral assets according to different rules of priority. Typically, the senior and the largest tranches are paid first and bear the least risk. The lowest or equity tranche is the first to be affected by default in the underlying collateral pool. In this manner, securitization provides access to funding sources from secondary capital markets. As the loans that comprise the pool are identified and warehoused, an iterative process involving the credit rating agencies attempts to maintain portfolio risk at acceptable levels. The special purpose vehicle finds an asset manager to trade the assets in the pool, a guarantor to provide credit guarantees on the performance of that pool and a servicer to process the cash flows generated from the pool and a trustee to oversee its activities. Figure 2 provides a pictorial representation of the entire process. As comfort with securitization products and structures grew, other types of financial assets were included in the assembly of the diversified portfolio. In addition to the usual individual fixed-rate and adjustable-rate mortgages and mortgage backed securities (MBS), the assets pooled into the securitization began to include loans and leveraged loans, high-yield corporate bonds as well as asset-backed securities (ABS). Thus the early collateralized mortgage backed obligation (CMO), were augmented by collateralized loan obligations (CLO), then by collateralized bond obligations (CBO), and later their aggregated version- the collateralized debt obligation (CDO). Figure 2 documents the recent growth in these assets. Once the securitization infrastructure was in place at most banks, new product development even involved the re-securitization of the lower (and more risky) CDO tranches into CDO-squared structures. Demand from private investors seeking yield in an environment of low interest rates began to mean that every conceivable cash flow stream was prone to being securitized. 2.1 Securitization and risk management. 2 These entities have been variously described as special purpose entities (SPE), structured investment vehicles (SIV), or Asset Backed Commercial Paper (ABCP) conduits. While there are differences in the way the different entities operate, their common feature is that they all are bankruptcy remote. 5 The process of tranching securities is the typical method by which the risks of securitization are managed. In a typical mortgage securitization, the collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) is a multi-class bond where tranche investors receive cash flows from reference assets in a collateral pool according to strict definitions of priority. Some tranches received only interest or only principal. Others allocated fixed rate payments to a floating rate and an inverse floating rate tranche, with different exposures to interest rate risk. Still others had explicit planned payment schedules, similar to a sinking fund to reduce uncertainty in payment times caused by variation in the speed at which mortgages are pre-paid. At times, some of the tranches were retained by the originating banks.3 However, as part of a mandate to promote home ownership, Fannie Mae initially issued its own debt and retained the interest rate risk rather than passing it through to investors. Typically, the debt issued to finance the mortgage acquisition was of a shorter duration than the mortgage that it finances. Declines in interest rates triggered refinancing by borrowers in fixed-rate mortgages. Although the mortgage gets prepaid, the financing must still pay off at the higher original rate causing a loss to Fannie Mae. If interest rates rise, the borrower retains the mortgage and Fannie Mae still bears the loss of having to refinance its loan at the new higher rate. This feature of mortgages is curiously referred to as negative convexity. The bank-like behavior of the GSE has inevitably resulted in the bank-like consequences of maturity mis-match that plagued the S&Ls. In response, the GSE’s initially increased the issuance of callable debt to counter the impact of interest rate changes and later to access the over-the-counter interest rate swap market to accomplish maturity transformation. Ironically, the SPV’s that were structured as ABCP conduits became subject to similar maturity mis-match problems in 2009 when money market funds lost confidence in the safety of that paper. 4 3 Recent proposals for financial reform are attempting to make the extent of this risk retention explicit. Some versions call for 5% ownership of the riskiest tranches while others call for retention of a portion of each tranche in a securitization. 4 Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2009) document the characteristics of the asset-backed commercial paper during the financial crisis. 6 Credit risk was initially managed by the GSE’s by strictly adhering to loan size, conformity and underwriting standards. As the mortgage market expanded, the guarantee business became a larger part of GSE operations. Loans that were bundled and sold as MBS came with a guarantee that the unpaid balances to security holders on individual mortgage defaults would be paid by the GSE. The GSE would then attempt to recover that amount through the foreclosure process. Therefore, the security holder would not have any exposure to credit risk. The Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) enabled the management of credit risk in much the same manner as the CMO. The extent of originator involvement in each tranche has remained opaque. From a signaling standpoint, originator ownership of the riskiest tranche could send a strong signal about the quality of the structured product to investors interested in the safer tranches. Table 1 documents the growth of this CDO structure in the last decade. As CDOs and other private lenders entered the securitization space, various types of credit enhancements began to proliferate.5 The quality of the collateral asset pool and concerns regarding adverse selection by pool originators resulted in several assurances, both internal and external.6 Internal guarantees include a cash reserve from setting aside a portion of the underwriting fee for creating the collateralized structure, or a portion of the interest received from the collateral assets, after paying interest on the tranches, or even by deliberate overcollateralization where the volume of collateral assets placed in the structure is greater than the volume of liabilities, thereby providing a layer of protection when some assets default. In addition to credit guarantees from the GSEs issuing the MBS, external guarantees were obtained from the sponsor and by the direct purchase of credit insurance from mono-line insurance companies or over-the-counter insurance through credit default swaps.7 5 Credit enhancement is a wonderful euphemism for loss distribution. 6 If originators have the most information about the quality of the underlying financial claims then it is reasonable to expect adverse selection on their part, only keeping the good loans and selling the bad ones. In the extreme, loan quality will decline across the board as demand for loans from securitizers weakens the incentive for originators to screen the loans This leads to issues of information asymmetry causing rational lenders to demand a lemonspremium, Duffie (2007). 7 Understandably, the level of these credit-enhancements was critical to obtaining a favorable rating from the rating agencies. 7 2.2 Securitization and credit risk transfer-the credit derivatives market. The credit default swap (CDS) emerged as the primary vehicle through which credit risk is transferred and traded.8 Simply stated, a CDS is a put option on credit risk.9 Buyers of protection from a credit event pay a periodic premium. If there is a relevant credit event that affects the value of the underlying asset, then the protection buyers are made whole by the protection seller and in this fashion they have shed the credit risk. Sellers of protection assume the credit risk in exchange for that periodic premium income. The appeal of the CDS becomes clear when it is compared with corresponding bond market transactions. Exposure to credit risk can be achieved either by owning the bond or selling the CDS. Owning the bond requires capital and also creates interest rate risk exposure while selling the CDS only requires mark-to-market adjustments and periodic collateral. Likewise, being short credit risk implies being either short the bond or buying the CDS. Again, the former is difficult to do while the latter is easy. In both cases, the CDS offers leverage and liquidity and is thus an easy expression of a view on credit in a manner that has not been possible in the secondary bond market. This “insurance” product has received considerable notoriety in the media. First, the direct purchase of a CDS without owning the underlying credit is akin to a short sale.10 Second, owners of the underlying credit can purchase protection against its possible default- an application similar to that of a protective put option. 11 Third, from initially insuring the default risk of bonds, the CDS market soon rapidly expanded to include CDS products on loans, mortgagebacked and asset-backed securities. Portfolio versions of these known as basket CDS and index 8 Although other structures like the Total return swap (TRS) and the Credit-Linked Note (CLN) are also related vehicles, we confine our discussion to the CDS instrument in the interest of brevity. Contract terms and definitions of the credit event are standardized by the International Swap Dealer’s Association (ISDA). More details on the CDS are available at www.isda.org. 9 Some commentators have urged that this use of a CDS is similar to taking out insurance on some one’s home and then burning it down to realize its value. The criticism here is not of the CDS instrument at all, but more an expression of discontent with the short selling in general. 10 Traditional forms of insurance incorporate the notion of “insurable” interest where the primary purchasers of insurance are those owners of assets who deem it necessary to seek protection against its loss of value. Restricting CDS purchases to this class of market participants is identical to only permitting protective put options to be traded and would thus limit the flexibility of market participants. 11 8 CDS products traded in the middle of the decade. The now notorious ABX and TABX indexes, are securities that take one or two deals from 20 different ABS programs, with 5 different rating classes-AAA, AA, AA, BBB, BBB-. The bottom two are further combined into the TABX which is the most sub-prime and experienced the most rapid declines in value at the beginning of the financial crisis.12 The synthetic CDO is a special purpose securitization vehicle that makes extensive use of the CDS instrument. The Bistro structure conceived initially by JPMorgan in 1997 became a template by which the cash flows to tranches of securitizations were generated from the premiums received by selling credit default swaps on a portfolio of underlying securitizable assets. In other words, instead of a pool of assets generating cash flows, the insurance premium representing their likelihood of default is itself distributed directly to the tranches. Since the default rate of the collateral pool governs the amount of the premium that will be received from credit default swaps sold on those assets, this amounts to essentially the same bet.13 3. Securitization and the financial crisis. Critics of securitization (Levitin, Pavlov and Wachter, 2009) argue that the securitization process was corrupted by the emergence of a shadow banking system in the late 1990s. These shadow banks are mortgage real estate investment trusts, insurance companies, private equity funds, the, money market funds, mutual funds, pension funds and hedge funds. Investment dollars from many of these institutions served as the “deposits” that the special purpose vehicles, CDOs and the housing GSE’s employed to fund securitizations. Gorton (2009) argues that this shadow banking system has developed as a consequence of several decades of integration of the traditional banking system with capital markets. By some measures about 60% of the credit system is facilitated by shadow banking (Date and Konczal, 2010). Indeed, commercial banks 12 As an illustration, the ABX.HE.A-06-01is an index of asset-backed (AB), home-equity loans (HE) assembled from ABS programs originating in the first half of 2006. The charges filed by the SEC in April 2010 against Goldman’s Sachs pertain to their lack of disclosure of information while such a synthetic structure was being created. 13 9 had little choice but to compete in this arena, since holding loans and funding them with deposits was not a profitable business for them anymore.14 The financial crisis of the last few years involved a series of runs on this shadow banking system. This was first visible in the asset-back commercial paper (ABCP) market and then in the repurchase market where institutions obtained short-term financing. The inability of the GSE’s to honor their guarantees on mortgage securitizations and that of AIG to meet its obligations from selling CDS insurance reverberated through the financial system. The response of the central banks to this ongoing crisis was coordinated and strong. The European Central Bank, The Bank of England, Her Majesty’s Treasury, the U.S Federal Reserve, and the U.S Department of the Treasury initiated several programs whose purpose was to “bailout” the shadow banks. Outright purchases of secured commercial paper and GSE obligations, the acceptance of securitized paper as collateral, the provision of liquidity facilities, capital and financing to private entities to purchase CMBS and private RMBS as well as non-mortgage MBS via the PPIP, TALF and TARP programs were some of the steps taken during the Fall of 2008 and Spring of 2009. The thinking behind these bailouts is that the Federal Reserve was better able to hold these assets either until maturity or until some point where the housing market recovered. The GSE’s are still requesting supplemental funds and thus far proposals for financial reform do not address their situation. This socialization of debt with all its welfare implications continues to this day with the recent events surrounding the PIIGS countries in Europe. With hindsight, it is easy to recognize that one implication of the diversification benefits that securitization provides to the senior and super-senior tranches is that it makes them effectively short correlation. Additionally, mortgage products are well known to exhibit negative convexity or concavity. Negative convexity essentially implies that they lose value when interest rates fall, partly because the rush of borrowers to refinance reduces the duration of the bonds. With correlated defaults, this effect becomes even more severe. At times of financial crisis, all 14 This was one of the motivations behind the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, which relaxed the separation of commercial and investment banking activities that were enshrined in the Depression Era Glass-Steagall Act. 10 correlations tend towards to unity, and it should not be surprising that these tranches that were rated as “safe” were adversely impaired.15 4. Securitization and regulation. Securitization is very closely linked to several aspects of rule-making. This section discusses how the various rules embodied in the bankruptcy code, derivatives regulation, Basel Accords and FASB guidelines have interacted with securitization activities. First is the remoteness from originator bankruptcy of the special purpose vehicles (SPV) that acquire assets via a “true-sale.” Early securitizations sometimes required multiple SPVs to accomplish this transaction. Legal opinions establishing the transfer of those assets were not clear and unambiguous, but carefully reasoned, very specific to the assets under consideration and often 40-50 pages long. In 2000, the FDIC issued the “securitization rule” stating that the FDIC would not use its statutory authority to repudiate “true-sale” contracts entered into during a securitization as long as GAAP principles were met. In 2005, the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act explicitly amended Section 541 of the Bankruptcy code to exclude assets transferred in an asset-backed securitization from the debtor’s estate, lending further support for securitization activities. Assets were deemed eligible for exclusion if they were rated as investment grade by one or more credit rating agencies. Second, accounting conventions pertaining to assets transferred to an SPV as a true-sale have undergone multiple changes in recent years, with modifications made pursuant to Enron’s abuse of the true-sale concept. Different incarnations of these rules were aimed at providing clarity regarding when the financial statements of an SPV should be consolidated with those of the financial institution sponsoring that securitization. FASB 167 adopted in June 2009, links consolidation more directly to the SPV’s purpose and design and a sponsor’s ability to direct the activities of the SPV that most significantly impact its economic performance. In March 2010, the FDIC introduced an extension to the 2000 securitization rule until September 2010 15 The assumptions regarding default and correlation in the models used by rating agencies did not anticipate this outcome resulting in a rash of severe ratings downgrades once the effect was noticed. 11 essentially grandfathering securitizations that commenced before these new GAAP standards were defined. Rating agencies have expressed concern that these guidelines make it less likely for senior tranches of securitizations to garner above investment grade ratings. Third, the risk transfers that make securitization possible received considerable impetus from derivatives regulation. Historically, the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) of 1936 required agricultural futures contracts to be exchange-traded. Under the Commodity and Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974, the CFTC became the new regulator whose role was expanded to include all exchange-traded futures contracts including financial futures. The adoption of a proposal from the U.S Treasury, called the Treasury Amendment, resulted in the exclusion of forward contracts such as those in foreign currency markets from regulatory supervision by the CFTC, ostensibly because they were over-the-counter instruments. The Futures Practices Act of 1992 extended this exclusion to interest rate swaps. Despite concerns regarding the OTC volume in these instruments, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 specified that any OTC derivative transactions between “sophisticated parties” would not be regulated as “futures” under the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) of 1934 or as “securities” under the federal securities laws. This fragmented regulation implied instead that banks and securities firms who are the major dealers in these products would instead be supervised under the “safety and soundness” standards of banking law and is at least partially responsible for the growth in the credit default swap market for transferring securitization risk. In August 2009, after the financial crisis and the collapse of securitization, regulation took a 180-degree turn when the US Treasury proposed legislation that essentially repeals many of the CEA exemptions above and argues for an exchange-traded market for CDS. Fourth, the evolution of minimum capital standards for banks, proposed in the various Basel accords were an attempt to globally regulate risk taking in the banking industry. Basel I had overly broad risk categories and did not tie regulatory capital charges to economic risk. Under Basel II, banks with deposits of over $250 billion had more stringent requirements which were optional for the smaller banks. Differential regulatory criteria for different banks created an incentive for regulatory capital arbitrage whereby such banks have “an incentive to sell the credit risk on loans whose regulatory capital exceeds their economic capital to institutions not bound 12 by the same capital regulations, and also to hold the credit risk on loans whose regulatory capital is below their economic capital,” [Hancock et al. (2005)]. Furthermore, the regulatory capital requirements gave considerable importance to the role of credit ratings. Capital charges were set at 8% and risk-weighted based on long-term credit ratings with weights ranging from 20% for AAA ratings to 350% for BB ratings. This implied that a $100 million loan would require $1.6 million in capital if it was rated AAA and $28 million in capital if the loan was rated BB. However, with the purchase of a CDS, a BB rated security could be transformed into a AAA rated one.16 Bake et al. (2010) document recent modifications to the Basel II capital requirements regime in response to the financial crisis. These include a treatment of resecuritization exposures designed to treat CDO structures, better stress testing, a value-at-risk framework and other operating constraints. 4.1 Commentary. Two key facets emerge from the evolution of regulation documented above. First, there is a reluctance to regulate that stems from the political philosophy of deregulation prevalent over the last few decades. The belief is that reputational considerations within the banking establishment will serve to monitor and limit excessive risk taking- a faith that appears misguided in light of the collapse of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and AIG. Reliance on rules-based legislation has also made it easier for the affected parties to circumvent them. Second, the centrality of rating agencies in the securitization process is clearly evident. Their importance is highlighted in bankruptcy law guidelines that exclude asset-backed securities from attachment in originator bankruptcy, in the risk-weighting schemes for banking regulation in the Basel accord and in the crafting of FASB standards for consolidating financial statements. While the enactment of the Credit Rating Agency Reform of Act of 2006 attempts to remove barriers to entry in the ratings market, concerns about conflict of interest still persist. These concerns were evident during past disruptions as well and essentially arise from a business model where the 16 The poster child for this activity was AIG and a quote from their 2007 10-K report states clearly that they sold CDS protection to European banks, “…. for the purpose of providing them with regulatory capital relief rather than risk mitigation in exchange for a minimum guaranteed fee”. 13 party desirous of obtaining a rating is the one that pays for the rating service. One proposal to limit this conflict of interest is to make the ratings a two-step process. An issuer desirous of a rating would pay the fee to a regulator (rather than directly to the rating agency) and the regulator would then assign one of several rating agencies to make the determination of credit quality. The choice of rating agency could be random or depend upon the complexity of the transaction and the rater’s ability to deal with that complexity. 5. Adapting securitization for emerging markets. Until the financial crisis, market participants in emerging markets expressed considerable optimism for securitization. As global markets have recovered, sporadic activity is visible in several locations, with investment banks, the ISDA and other industry professionals are setting up offices and recruiting staff. However, the progress in terms of official approvals and their commitment is slow. Without an institutional structure, efficient legal system, well-defined bankruptcy laws, and accounting practices, principal-agent conflicts and information symmetry will continue to be significant issues in market development. This section first surveys securitization activity in different emerging markets and then provide some guidelines in terms of how these activities may be developed further. 5.1 Market Development. In emerging markets, the need for long-term projects in infrastructure,- roads, bridges, power and water facilities, oil and gas facilities and telecommunications energy, create securitization opportunities for the associated receivables. As one would expect, the progress of securitization efforts varies within individual emerging economies and depends largely on their laws, regulatory frameworks and the range of activities that domestic institutional investors are permitted. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, is permitting foreign ownership of real estate and Saudi Arabia had declared an intention to create a Fannie Mae like structure. Some Asian countries have some form of government-sponsored mortgage corporations while others do not. Domestic pension funds, insurance companies and hedge funds in Latin America 14 are natural consumers for different securitized tranches but are not so active in some parts of Asia. The benefits of a local currency CDS market for bank management of credit risk are widely recognized and there is some preference for synthetic products. Relationship banking is extremely entrenched in many countries and it is often not considered culturally appropriate to transfer risk in the manner that credit derivatives enable. Non-performing loans were first securitized in some regions while others targeted the residential and commercial mortgage market. Early structured products were aimed at institutional investors in the developed world who might desire exposure to the region but these efforts are broadening towards the development of domestic markets. Asian assets for CDO structures appear to be generally lower quality and less diversified. It would appear that equity tranches would have to be thicker to accommodate the high correlations that are perceived to exist in credits even across countries in the region. In Hong Kong and Singapore, there is some evidence of customized single-tranches for institutional clients. Some securitizations aggregate assets from local as well as developed markets. In addition to Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, Hong Kong, Mexico and Brazil are the most accepting of credit derivative products. Unique circumstances in each region have spawned the development of specific products. Singapore has attempted securitization of loans to small and medium sized enterprises (SME). In Russia, second-tier banks are warehousing mortgages until the pool is big enough to tap capital markets. Microfinance securitizations are being proposed in other countries with a recent success in India in the fall of 2009. In China, regulatory oversight and rules for mortgage securities are being discussed and pilot projects for securitization trials are underway. Some securitizations of domestic non-performing loans have been completed. In 2005, a specific asset management plan (SAMP) was introduced where a domestic securities firm would raise capital from investors and allocate it to specified corporate (non-bank) assets. While similar in spirit to the SPV securitization structure, the 15 SAMP’s status as a legal entity with features of bankruptcy-remoteness are still unclear. Some rulings regarding the simplification of tax treatments involving VAT and stamp duty have been announced. In India, following the success of the rupee swap market, the Reserve Bank of India has recently released guidelines for the use of rupee denominated, plain-vanilla credit default swaps (CDS) by resident institutions. As presently conceived, this will pertain to a single reference entity (such as a bond or bank loan). Both cash and physical settlement are permitted and the focus is on hedging and diversifying balance sheet assets. Banks are not yet permitted trading and marketmaking activities, but it is hoped that this will eventually pave the way for broader market participation. In 2009, the first micro-finance securitization was rolled out by ICICI bank which pools together small loans made micro-finance lending agencies and tranches out the cash flows to mutual funds. Here again, securitization provides a funding source to promote lending. 5.2 Issues and processes related to managing credit risk. Structured credit securitization creates new risks at the same time that it enables the market players to diversify pre-payment risk or credit risk. Many of these new risks are linked. As always, they arise from the conduct and practices of participants as they operate in and attempt to price complex securities during times of market turbulence. The section below briefly describes these risks and urges attempts to redefine and refine existing conventions as well as efforts to develop new processes for risk management. 5.2.1 Operating considerations. The use of credit derivatives will require a drastic re-thinking of the way banks currently process their operations. Risk management structures must be in put in place to deal with operating risk. Operating risk results from the trading and conduct of market participants during clearing, confirmation and settlement—again processes that are particularly vulnerable at times of market stress. In most emerging markets, there is a large gap between the sophistication of financial products and the level of financial literacy. Local staff, skilled in credit products and 16 securitizations may be hard to find and have to be trained. Best practices and codes of conduct for market participants throughout clearing, confirmation and settlement are necessary. Before the transaction, these would include a knowledge of the counterparties’ familiarity with complex trades, agreements on how open positions are carried and a review of the main contractual terms. Execution should be confirmed in a timely fashion. If it is delayed, all parties should be notified and provided reasons. Valuation information should be exchanged after the transaction. Reliable systems for internal reporting should be developed and maintained. Electronic platforms for clearing and settlement should be devised as appropriate. 5.2.2 Mark-to-market accounting practices The need for greater transparency of complex financial transactions and their globalization has catalyzed a move towards the adoption of “fair value” or mark-to-market accounting by both the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). To its adherents, fair value accounting reflects the true value of assets on the balance sheet and thus permits investors to better assess the risks therein and allows policy makers to better adjust their responses. In the US, FASB 157 came into effect in November 2007. Under FASB 157, assets are broken up into three classes. Level I assets are those that have observable market prices and are “marked-to-market.” Level II assets may not have observable secondary market prices, but the models that price them should have market data as inputs. This is more commonly referred to as “marked-to-model” and is quite a ubiquitous phenomenon. For instance, bond markets are notoriously thin and even in the U.S, less than 3% of the outstanding stock trades on a given day. Level III assets are those for whom even observable market inputs are not available. These would obviously include assets such as complex CDO tranches and CPDOs. Valuation practices in this class are little more than guesses and are sometimes referred to as “marked-by- 17 management.” Quite naturally, this leads to concerns about how financial institutions might game favorable reporting outcomes17. Critics of fair value accounting have long maintained that it is not altogether without flaws and transmits the volatility in market prices to balance sheets and to corporate earnings. In other words, market prices cannot be trusted at times of crisis. Allen and Carletti (2006) argue that marking assets to market prices is particularly unreliable if the underlying markets that generate those prices are illiquid. Rather than reflecting future cash flows, illiquid prices may merely reflect the cash available to market participants. In their model, mark-to-market accounting contributes towards the onset of contagion in ways that historical cost accounting does not. 5.2.3 Model Risk. Model risk refers to the increasing dependence on complex, often proprietary pricing models and a lack of recognition of the model’s limitations. The key inputs into most models are assumptions about default rates and recovery rates for single-name products and additionally, default correlations for multi-name products. In some emerging markets, validated, reliable data for comparative risk analysis, such as a time-series of loan-losses, default histories and recovery rates may not be available. Even with historical data and an active secondary market to calibrate model values, correlation assumptions in existing models for multi-name products do not provide reliable and consistent results. Model risk is exacerbated when tail events dominate markets as at present, and extant Value-atrisk (VAR) models underperform significantly. Adjustments to model tolerances during such and other regime shifts are often not made in a timely manner. Indeed even the tendency of modelers to view the statistical world as Gaussian and therefore, departures from it as “tail” risk may need to be re-examined. Ironically, model risk receives a bad name because model imperfections are revealed at times when investors need them the most! Academics will argue however, that the 17 Weil (2007) describes that Wells Fargo Bank in a recent filing reported $2.24 billion of losses in Level I and Level II assets while simultaneously reporting $2.04 billion of gains in Level III assets. The latter are much harder to verify than the former. 18 practice of modeling provides insights in to the types of risks that lurk in complex products. Lastly, over-reliance on complex models can also be counterproductive in that they absolve risk management executives from exercising judgment and conducting due diligence. VERMA 5.2.4 Counterparty risk Third-party or counterparty risk relates to the non-performance of loan originators, loan servicers, asset managers and other counterparties. Hedge funds have been particularly active in the subprime mortgage space. Some have already been liquidated, while others have received capital infusions from sponsors to enable a more gradual unwinding of their positions. A recent paper by Bollen and Pool (2007) argues that hedge fund managers avoid reporting losses to retain investors. Specifically, they find that the frequency of small gains is higher than that of small losses, and that this is not visible prior to an audit, or for funds that invest in liquid assets. They do however speculate that hedge fund managers may be optimistic about the value of their illiquid holdings. 5.2.5 Legal risks Simply appealing to standardized documentation from ISDA in developing CDS markets is not sufficient. Legal risk can arise when deal documents are modified by counterparty lawyers (often subtly). The bankcruptcy-remote character of the SPE may not always be watertight. Shariah law tends to be principles based and permits domestic courts considerable leeway interpretation and applicability to specific transactions. While this may appear to be an advantage given the failure of rules-based regulations in the West, the lack of clarity about legal title and enforcement can result in unpredictable outcomes. For instance, Shariah law does not clearly separate legal and equitable title, and, therefore, “true sales” in Shariah locations have to structured appropriately so that a sale of the legal interest in the collateral to the SPE satisfies all applicable Shariah requirements. Some legal systems have required that both a local and an offshore SPE be created for a securitization to be in compliance. 5.2.6 Liquidity risk. 19 Liquidity risk is a concern both when transactions require funding and when transactions affect prices. From a funding perspective, timing differences between collateral cash inflows and tranche cash outflows are common in most securitizations. As mentioned earlier, ABCP and SIV structures address this through some combination of short-term and long-term borrowing. Their ability to rollover debt, meet the cash, margin and collateral requirements of counterparties to the transaction and manage withdrawals of capital are critical. In the current credit crunch, the injections of liquidity by central banks represent a broader effort to maintain short-term liquidity flows. Despite this, inter-bank spreads have continued to widen and financial institutions appear to still “hoard” liquidity. From a trading perspective, liquidity risk refers to the impact on prices when transactions are executed. For instance, if there is considerable herding of market participants, then this form of liquidity risk manifests itself as an inability to execute a transaction without significantly affecting prices. This is typically because of the lack or unwillingness of parties to take the other side. Both herding and liquidity risk contribute to the distress prices at which the few reported transactions of sub-prime portfolios are currently taking place. In emerging markets, the message of the Asian crisis of 1997 still resonates among policy makers who view managing capital flows as an important concern. The focus has been on “hot money’ hedge funds and their power to destabilize small capital markets. It is however becoming apparent that the hedge funds sponsored by some of the larger and more reputed Western financial institutions also operate in a similar manner. In other words, there is substantial herding behavior amongst institutional investors and targeting specific entities for regulatory supervision is likely to miss the larger picture. From a longer-term perspective, there is some evidence that domestic institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies are likely to provide a countervailing force against such capital flows. Fostering such an environment for domestic institutions should continue to be a parallel goal for policy makers in emerging markets. 6. Conclusions. 20 This paper documents the linkages between asset securitization activities and the financial crisis of the last few years. It provides an overview of the securitization process and how borrower credit risks and market-wide interest rate risks are managed within that process. It documents the legal and regulatory underpinnings in western societies that made securitization so accessible to market participants. The paper concludes with a review of how emerging economies can learn from these developments in starting securitizations in their locations. 21 References Bake, M., K. Hawken, C. Hitselberger, R. Hugi and J. Kravitt, 2010, “Basel II Modified in Response to Financial Crisis,” Journal of Structured Finance, 15(4), 19-28. Date, R. and M. Konczal, 2010,” Out of the Shadows: Creating a 21st century Glass-Steagall,” in Make Markets, Be Markets, The Roosevelt Institute Project on Global Finance. Duffie, 2007, “Innovations in Credit Risk Transfer: Implications for Financial Stability,” Working Paper, Stanford University. Fender I. and S. Mitchell, 2009, “The Future of Securitization: How to align the incentives,” Bank of International Settlements, September. Gorton, G. and A. Souleles, 2005,”Special Purpose Vehicles and Securitization,” National Bureau of Economic Research. Gorton, G., 2009a, “Slapped in the Face by the Invisible Hand: Banking and the Panic of 2007,” Remarks at the Financial Innovation and Crisis Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Gorton, Gary and Andrew Metrick 2009b, “Securitized Banking and the Run on Repo,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1440752. Gorton, 2010, Questions and Answers about the Financial Crisis: Prepared for the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, 1-17. Hancock, D., A. Lehnert, W. Passmore and S.M. Sherlund, 2005, “An Analysis of the Potential Competitive Impacts of Basel II Capital Standards on US Mortgage Rates and Mortgage Securitizations, Federal Reserve Board. Kacperczyk M. and P. Schnabl, 2009, “When Safe Proved Risky: Commercial Paper During the Financial Crisis of 2007-2009,” Working Paper, NYU Stern School of Business and NBER. Levitin, A.J., A.D. Pavlov and S. Wachter, 2009, “Securitization: Cause or remedy of the financial crisis?” University of Pennsylvania Law School Research Paper No. 09-31. Loutskina, E, 2005,”Does securitization affect bank lending?Evidence from bank responses to funding shocks,” Carroll School of Management, Boston College. Jiangli, W. and M. Pritzker, 2008,” The impacts of securitization on US bank holding companies,” http://ssrn.com/abstract=1102284. Robinson, K.J, 2009, “TALF: Jump-Starting the Securitization Markets,” Economic Letters, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas 4(6), 1-7. 22 Sabry, F. and C. Okongwu, 2009, “Study of the Impact of Securitization on Consumers, Investors, Financial Institutions and the Capital Markets,” NERA Economic Consulting for the American Securitization Forum, 1-241. 23 Figure 1 The structure of securitization Guarantor Asset Manager ManaMana Trades Assets ger Loans Mortgages Originator (sponsor, pools assets) Insures Tranches Senior SPECIAL PURPOSE VEHICLE Assets | Liabilities True-sale assets Funds funds from Bond sales payments from pool Bonds Mezzanine Equity Collects CF from pool Oversight INVESTORS Servicer Trustee Source: Adapted from Fender and Mitchell (2009) 24 Figure 2 Types of securitization activities in US markets, 2000-08 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 2000 2001 Agency MBS 2002 2003 2004 Non-Agency MBS 2005 CMBS 2006 2007 ABS 2008 CDO 25 Table 1 Global CDO Issuance ($ billions) through 2009 Panel A1 Panel B Total _______________________ _______________ Period CDO Cash and Synthetic Market Arbitrage Balance Issuance Hybrid Funded Value Sheet CDO CDO (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Panel C2 _____________ Long Short Term Term (7) (8) 1H-04 67.8 44.6 23.2 0.0 62.8 5.0 50.1 17.7 2H-04 89.6 74.9 14.0 0.7 84.2 5.4 72.8 16.8 1H-05 108.5 90.8 17.5 0.2 93.2 15.3 105.3 3.2 2H-05 142.8 115.8 27.0 0.4 120.1 22.7 139.4 3.4 1H-06 214.8 178.8 33.1 2.9 190.6 24.1 210.3 4.5 2H-06 305.9 231.7 33.4 40.7 264.3 41.6 291.4 14.5 1H-07 345.1 256.1 40.4 48.6 308.6 36.6 331.5 13.7 2H-07 136.5 84.3 8.0 44.1 123.3 13.2 133.8 2.7 1H-08 41.9 28.6 1.2 12.1 34.0 7.9 41.9 0.0 2H-08 20.0 15.0 0.2 4.8 13.9 6.1 20.0 0.0 1H-09 2.6 1.5 0.1 1.0 2.5 0.1 2.6 0.0 2H-09 1.6 0.9 0.2 0.5 8.5 7.1 1.4 0.2 ______________________________________________________________________________ Panel A presents a breakdown of total issuance by CDO type. Panel B presents a breakdown of total issuance by CDO strategy. Panel C presents a breakdown of total issuance by CDO tranche maturity. The sum of the columns in each panel should equal the figures in Column (1). Unfunded CDO’s are not included in the figures in Panel A. Therefore these estimates understate the volume of activity. 1 2 Long-term refers to tranches with more than 18 months to maturity. Data are from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). 26