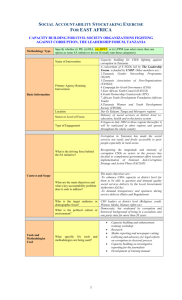

Business Case - Intervention Summary

advertisement