OR Fires 2011 - Arkansas Hospital Association

advertisement

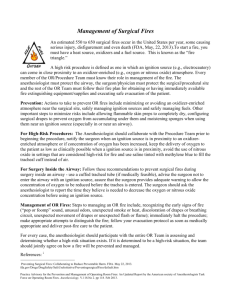

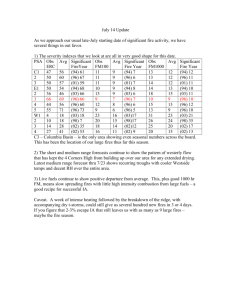

Prevention and Management of an OR Fire Speaker Sue Dill Calloway RN, Esq AD, BA, BSN, MSN, JD CPHRM President Patient Safety and Health Care Consulting 5447 Fawnbrook Lane Dublin, Ohio 43017 614 791-1468 sdill1@columbus.rr.com 2 Headlines You Don’t Want to See 3 A Patient Seriously Burned from an OR Fire 4 Another Patient Seriously Burned 5 4 Year Old in OR Fire Case 6 Surgeon Accused of Covering Up OR Fire 7 New Clinical Guide to Surgical Fires ECRI and the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation have issued new clinical guidelines to surgical fire prevention Recommendations include two important things Eliminate the traditional practice of open delivery of 100% oxygen during sedation Securing the airway is recommended if the patient requires an increased oxygen concentration The surgery team should talk about the risk of a surgical fire before each surgery 8 New Clinical Guide to Surgical Fires Surgical fires is one of the three never events along with wrong site surgery and leaving an instrument in the patient 65% of fires occur with high concentrations of oxygen around the face, neck, and upper chest Fires in oxygen rich atmospheres ignite more easily, burn hotter, and spread quicker The goal is to stop open oxygen delivery around the head and upper chest If oxygen is needed use the minimum and follow the new guidelines 9 New Clinical Guide to Surgical Fires Carefully arrange surgical drapes to minimize oxygen build up underneath Always make sure the surgical prep is dry before draping Use only air for open delivery to the face Provided that a spontaneously breathing sedated patient can maintain his or her blood oxygen saturation without extra oxygen 10 New Clinical Guide to Surgical Fires If the patient cannot maintain safe blood oxygen saturation without supplemental oxygen, secure the airway by using a laryngeal mask airway or tracheal tube, so that oxygen-enriched gases do not vent under the surgical drapes Discontinue the traditional practice of open delivery of 100% oxygen with limited exceptions Suggest may want to require that all staff watch the video on surgical fire prevention and management It includes the new recommendations for controlling oxygen delivery by minimizing the presence of oxygen rich environment of the head, face, neck and upper chest 11 Fire Safety Video http://www.apsf.org/resour ces_video.php 12 Fire Safety Video APSF or Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, with the assistance of ECRI, has a 18 minute video On Prevention and Management of an OR Fire Anyone can watch the video on their computer Can also request a complimentary DVD copy Available at http://www.apsf.org/resources_video.php 13 ECRI’s Surgical Fire Prevention Website www.ecri.org/surgical_fires 14 ECRI Has 2 Posters for Your OR Only You Can Prevent Surgical Fires – Oxygen and nitrous oxide increase the flammability of drapes, plastics, and hair – Do not apply drapes until all flammable preps have dried as oxygen can be trapped under the drapes – Moisten sponges to make them ignition resistant in oropharyngeal and pulmonary surgery – Fiberoptic light sources can start a fire. Complete all cable connections before activating the source. Place the source in the standby mode when disconnecting cables 15 ECRI Has 2 Posters for Your OR Only You Can Prevent Surgical Fires (continued) Has important recommendations for surgery during head, neck, face, and upper chest surgery since 65% of the burns occur here Begin with a 30% delivered O2 and increase if necessary For unavoidable open O2 delivery above O2, deliver 5 to 10 L/min of air under the drapes to wash out the excess O2 Poster includes recommendations during oropharyngeal surgery, tracheostomy, bronchoscopic surgery and when using electrosurgery, lasers, or electrocautery 16 Posters for the OR 17 18 19 Emergency Procedure Extinguishing a Surgical Fire 20 AORN Poster 21 Could You Catch Fire During Surgery? Fires in operating rooms happen at least 600 times a year ECRI has 1 to 2 fires reported to them per week Pa Patient Safety Authority cited the chances of a surgical fire in Pa at 1 in 87,646 operations For Pa this averages 28 surgical fires per year Could You Catch Fire During Surgery? Only 5% of the fires cause harm to patients 10-20 patients are seriously burned every year 1 to 2% are fatal Mostly involving airway fires 70% of fires involve electrosurgery equipment 10% involve lasers 20% are electrocautery equipment and fiberoptic light sources 23 What Are the Highest Surgical Fire Risks? The following examples of high-risk procedures provided by ASA are ranked in descending order based on fire incidence: Removal of lesions on the head, neck, or face Tonsillectomy Tracheostomy Burr hole surgery Removal of laryngeal papillomas Source: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires. Anesthesiology 2008 May;108(5):786-801. 24 Pa Patient Safety Authority http://patientsafetyauthority.org/ADVISORIES/AdvisoryLibrary/2010/Jun7(2)/ Pages/60.aspx 25 Airway Fires During Surgery 26 Did You Know? 75% involve oxygen enriched atmospheres under surgical drapes Oxygen enriched atmosphere are created when oxygen at concentrations above 21% in ambient air provided by face mask, ET tubes or nasal cannula 4% involve alcohol-based skin prepping agents Location of Surgical Fires 44% face, head, neck and chest Another source (APSF) says 65% 21% airway 26% elsewhere on the body 8% elsewhere in the body Source: ECRI Surgical Fires July 2010 Fire Triangle Preventing OR fires is a team approach Each member of the surgical team is involved with one or more sides of the triangle • Ignition sources • Oxidizers • Fuels 29 Ignition Sources Surgeons usually have the ignition source Electrosurgical or Electrocautery devices Lasers, heated probes Drills and burrs, argon bean coagulators Fiberoptic light cable sources Defibrillators paddles or pads Ignitions sources are 70% electrosurgery, 10% laser, and 20% are cautery, light sources, bur sparks, or defibrillators Oxidizers Anesthesia usually bring the oxidizers Oxygen-enriched atmospheres Nitrous oxide Medical compressed air Ambient air Fuels Nurses usually bring the fuel Make sure the surgical prep is dry!!! Surgical drapes, mattresses, sheets, gowns, towels, etc Volatile organic chemicals, packing material Body hair, gloves, smoke evacuator hoses, flexible endoscopes Intestinal gases and tracheal tubes Body tissue, adhesive tape, ointments Aerosol adhesives, Alcohol, Degreasers (ether, acetone) Tinctures and surgical skin prep (Hibitane, DuraPrep, Chloraprep, etc.) – The list is seemingly endless Do You Know the Following? Is the hallway free of clutter? Where is the oxygen or medical gas shut-off valve? What is the coverage area of this zone? Where is the fire alarm pull stations and exits? Where is the hallway fire extinguisher, and what type is it? Who is the spread of smoke prevented? By closing the doors or using smoke doors and air-duct dampers Source:. Steelman VM. Where there's smoke, there's ... AORN Journal 2009; 89:825-827. Do You Know the Following Where is the fire extinguisher in the OR, and what type is it? Does top management create a culture that is supportive of fire prevention? How would you evacuate from this OR? Stretcher or OR table in corridors When and how do you communicate with the OR, within the suite, with the rest of the facility and with the local fire department? 34 Do You Know the Following? How do you operate the fire extinguisher? Is the path to the extinguisher accessible? Is there saline on the sterile field? Where is the self-inflating ambu bag? Where is the flashlight? Can also use these during practice drill Perioperative briefing to identify high risk procedures before every case 35 www.mdsr.ecri.org/static/surgical_fire_poster.pdf 36 ASA Practice Advisory ASA or the American Society of Anesthesiologists has a free 16 page practice advisory on the prevention and management of operating room fires Published in 2008 Defines the following; Operating room fires are defined as fires that occur on or near patients who are under anesthesia care, including surgical fires, airway fires, and fires within the airway circuit 37 ASA Practice Advisory A surgical fire is defined as a fire that occurs on or in a patient An airway fire is a specific type of surgical fire that occurs in a patient’s airway. Airway fires may or may not include fire in the attached breathing circuit OR fires can cause burns, inhalation injuries, infection, disfigurement, and death ASA recommends that every anesthesiologist should have knowledge of OR fire safety protocols 38 ASA Practice Advisory ASA recommends that every anesthesiologist participate in OR fire safety education Education should emphasize the risk created by an oxidizer enriched atmosphere ASA recommends that anesthesiologist participate in OR fire drills and simulation training with the entire OR team Team should determine if high risk situation exists If yes then a discussion of the strategy to prevent an OR fire 39 ASA Practice Advisory The protocol to prevent and manage fires should be posted in each location where a procedure is performed Each team member should be assigned a specific fire management task to perform in the event of a fire Remove the ET tube, stop the flow of airway gases, douse with saline, etc. Study showed that the configuration of surgical drapes can result in oxygen build up increasing the risk of fire 40 ASA Practice Advisory Studies show that replacing oxygen with compressed air or discontinuing supplemental oxygen for a period of time will reduce the oxygen build up without reducing oxygen saturation levels Studies found that lasers, electrosurgical or electrocautery devices are a common source of ignition for many OR fires Cases found the alcohol based skin prep agents generate volatile vapors that ignite easily Insufficient drying time is cause of many fires 41 ASA Practice Advisory Studies show that conventional tracheal tubes are more likely to ignite or melt that laser resistant tracheal tubes when exposed to a laser Dry sponges and gauzes are common sources of fuel Flammability of sponges, cottonoids, or packing material is reduced when wet ASA has an operating room fire algorithm Is it a high risk procedure, are there early warning signs of a fire, airway or non-airway fire 42 43 ASA Practice Advisory Surgeon should be notified when an ignition source is in proximity to an oxidizer enriched atmosphere or when the concentration of oxidizer has increased Oxygen delivered to the patient should be as low as clinically feasible when ignition source is in proximity to an oxygen enriched atmosphere Reduction of oxygen (fraction of inspired oxygen or FIO2) is guided by monitoring the pulse ox This should include measuring inspired, expired, and or delivered oxygen Use of nitrous oxide should be avoided in settings that are considered high risk for fire 44 ASA Practice Advisory For laser surgery, the cuff of the ET tube should be filled with saline instead of air The saline should be tinted with methylene blue to act as a marker for cuff puncture by a laser For cases involving surgery inside the airway, a cuffed tracheal tube should be used when medically appropriate Surgeons should be advised not to enter the trachea with an ignition source such as an electrosurgical device 45 ASA Practice Advisory If surgery around the face, head, or neck and sealed gas delivery device is needed then use a cuffed tracheal tube or laryngeal mask Sealed gas should be considered if exhibits oxygen dependency during moderate or deep sedation If open gas system is using, such as a facemask or nasal cannula is used, and surgery around face, neck or head, surgeon needs to give notice before ignition source is activated Anesthesiologist need to stop the O2 or reduce delivery and wait a few minutes before activation of the ignition source 46 ASA Practice Advisory Management of OR fires Early signs of a fire may be a flame or flash, unusual sounds, odors, smoke, or heat Halt the surgery Remove the tracheal tube for an airway fire or fire in the breathing circuit and stop the oxygen Pour saline into the tracheal tube If fire in the patient or elsewhere remove all drapes and burning material and extinguish (saline, water, smothering) 47 ASA Practice Advisory https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-303-practice-advisory-forthe-prevention-and-management-of-operating-roomfires.aspx 48 ASA Practice Advisory https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-303-practice-advisory-for-theprevention-and-management-of-operating-room-fires.aspx 49 50 TJC – Sentinel Alert #29 TJC issues Sentinel Event Alert (SEA) 29 on June 24, 2003 on Preventing Surgical Fires Also issued SEA 17 on Fires in the Home Care Setting SEA 39 focused on understanding & mitigating fire risks rather than prohibiting patient care products Discusses how you need all three things of the fire triangle to start a fire Heat fuel, and oxygen www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_a lert_issue_29_preventing_surgical_fires/ 52 SEA 17 Fires in the Home Care Setting www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_ 17_lessons_learned_fires_in_the_home_care_setting/ 53 TJC 3 Recommendations Everyone should be aware of the importance of controlling heat sources by following laser and electrosurgical units (ESU) Manage fuel by making sure all preps (chloraprep, etc.) have had enough time to dry Establish guidelines for minimizing oxygen concentration under the drapes Develop, implement, and test procedures to ensure appropriate response to all surgical team members in the event of an OR fire Report any surgical fires to TJC, ECRI, FDA, state agency 54 TJC Data on Sentinel Events TJC reported 7391sentinel events from January of 1995 through December 31, 2010 There were 68 fires TJC evaluated these fires to determine their root causes The most common root cause was communication which resulted in 33 fires If a hospital experiences a surgical fire TJC has a matrix which includes which issues should be evaluated 55 Root Cause of Fires by TJC 56 57 TJC Sentinel Event Alert 29 Preventing Fires www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_i ssue_29_preventing_surgical_fires/ 58 CMS Hospital CoP Hospitals that accept Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement must follow the hospital conditions of participation The CoPs requires hospitals to have a safe environment Tag 702 requires hospital to comply with the LSC National Fire Protection Amendment or NFPA 101 Tag 709 states must ensure life safety from fire Tag 714 requires the hospital to have written fire control plans that contain provisions for prompt reporting of fires 59 www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/som107_Appendi cestoc.pdf 60 CMS Hospital CoP Must report all fires to the state fire marshal This would include having procedures to prevent and respond to a surgical fire CMS has the following on page 327 Tag 951 Use of Alcohol-based Skin Preparations in Anesthetizing Locations. Alcohol-based skin preparations are considered the most effective and rapid-acting skin antiseptic, but they are also flammable and contribute to the risk of fire 61 CMS Hospital CoP CMS also note the following under tag 951 There is concern that an alcohol-based skin preparation, combined with the oxygen-rich environment of an anesthetizing location could ignite when exposed to a heat-producing device in an operating room. Specifically, if the alcohol-based skin preparation is improperly applied, the solution may wick into the patient’s hair and linens or pool on the patient’s skin, resulting in prolonged drying time. Then, if the patient is draped before the solution is completely dry, the alcohol vapors can become trapped under the surgical drapes and channeled to the surgical site. 62 63 CMS Prep Must Be Dry 64 CMS Hospital CoP This would include having procedures to prevent and respond to a surgical fire CMS issued a memo in 2004 on the procedure to follow in the event of a fire Fires are to be considered a priority assignment of immediate jeopardy CMS will consider all fires with serious injury or death to be entered into their computer system as a complaint or self reported incident State agency will compile information about the fire and perform a life safety code investigation 65 CMS Memo http://www.cms.hhs.gov/SurveyCer tificationGenInfo/downloads/SClett er04-23.pdf 66 Many Resources to Consider ECRI Institute ASA or American Society of Anesthesiologist APSF or Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation AORN Fire Safety Toolkit or Association of periOperative Nurses TJC Sentinel Event Alert National Guideline Clearinghouse MDSR – Medical Device Safety Reports ASHE OR Fires Introduction Develop a fire safety plan Make sure OR has appropriate firefighting equipment See later section on use of extinguishers Focus on education Fires are less likely to occur if they act as a team And if surgical team understands their causes and how to respond should one occur OR Fires Introduction Develop an effective fire drill program Drills enable the staff to learn the plan and test the effectiveness of he plan Helps to identify areas of improvement Schedule drills so surgeon and anesthesiologist can participate Evaluate performance during surgical fire drill Have a competency tool for staff Do an annual literature review and update the policy as needed 69 OR Fires Introduction Have one person assigned to be the OR fire safety officer Require mandatory education in orientation and during annual skills lab Do a self assessment on risk of fires Report all fires and document Have policies in procedures in effect Watch the video on preventing fires by A Whatever you do don’t think this can’t happen to you! 70 Fire Risk Assessment AORN Fire Safety toolkit has a fire risk assessment tool Circulating nurse completes the risk assessment to determine the risk level Risk levels include A, B, C, D, or E Circulating nurse reports this during the time out The interventions are taken from the policy and procedure for Fire Safety in the Perioperative Setting It contains actions for each of the risks 71 AORN Fire Risk Assessment Tool 72 Fire Risk Assessment A. Is there an alcohol based prep or other volatile chemical being used? If yes then prevent pooling of skin prep, removed soaked linen, allow skin prep to dry, conduct skin prep time out, etc B. Is the surgery being performed above the xiphoid process? If yes then coat head and facial hair near the surgical site with water soluble lubricant, use adhesive incise drape etc. 73 Fire Risk Assessment C. Is open oxygen being used? If yes, then configure surgical drapes to allow sufficient venting of oxygen delivered by mask or cannula, deliver 5 to 10 L/min of air under the drapes to flush out excess oxygen, titrate O2 to lowest %, use cuffed ET tube when possible, stop supplement O2 for one minute before electrosurgery, electrocautery or laser for head, neck, or upper chest procedure etc. D. Is an ESU, laser, or fiber-optic light cord being used? E. Are there other possible contributors like a defibrillator, drills, saws, burrs etc. 74 Prevent OR Fires During Prep Be aware alcohol based preps are flammable Avoid pooling or wicking of flammable liquid preps Allow flammable liquid preps to dry fully before draping Spilled or pooled agent should be soaked up and removed from the patient Prevent OR Fires During Prep Proper application of an incise drape ensures that there are no gas communication channels from the under- drape space to the surgical site Remove towels used to catch dripped flammable prep before draping Keep fenestration towel edges as far from incision as possible About 4% of all fires are due to alcohol bases surgical preps These fires are devastating because they are often undetectable The blue-yellow flame of an alcohol fire can be invisible under the bright surgical lights 76 Preventing OR Fires During Electrosurgery Place electrosurgical pencil in holster when not in use Place unit in standby mode when not in active use Allow the electrosurgical active electrode to be activated only by the person wielding it Activate active electrode only when tip is under surgeon’s direct vision Deactivate the unit before the active electrode tip leaves the surgical site Instrument can momentarily retain sufficient heat for fuel ignition Preventing OR Fires During Electrosurgery If open O2 source is use, use bipolar electrosurgery when possible and clinically appropriate since bipolar creates little or no sparking or arcing Never use electrosurgery to enter the trachea 78 Preventing OR Fires During Electrosurgery Never use electrosurgery in close proximity to fuels in oxidizer enriched atmosphere Never forget may need to turn off valve for medical gases such as oxygen Consider the use of non-thermal surgical therapies for cutting and coagulation 79 Reducing Likelihood of Airway Fires Have policy when electrosurgery will be removed from the surgical field because of risk of fire Some hospitals remove the unit when the trach tube is put on the surgical field Do not use electrosurgical units to cut tracheal rings and enter the airway A hot electrode tip or ember could contact the tube or tube cuff inside the trachea and ignite a fire Instead, use a “cold” scalpel or scissors to avoid the risk of fire 80 Reducing Likelihood of Airway Fires If long, insulated electrosurgical electrode probes are needed to prevent mouth burns during procedures such as tonsillectomies, use only commercially available insulated probes Do not use red rubber catheters or other materials to sheathe probes The heat from the active electrode will ignite the rubber even in air When operating in the oropharynx, scavenge around the surgical site with separate suction to catch leaking O2 and nitrous oxide 81 OR Fires in General Coat facial hair (including eyebrows, beard, and mustache) near the surgical site with water-soluble surgical lubricating jelly to make the hair nonflammable Be aware of the flammability of tinctures, solutions, and dressings (such as benzoin, phenol, and collodion) used during surgery, and take steps to avoid igniting their vapors Moisten sponges to make them ignition resistant in oropharyngeal and pulmonary surgery Minimizing Fires During Laser Surgery https://members2.ecri.org/Com ponents/HRC/Pages/SurgAn17 .aspx 83 Prevention of Fires During Laser Use Lasers are used to cut, vaporize, or remove tissues Despite their many benefits, lasers can pose some risks such as burns Patients have been severely burned by laser-ignited fires Class 4 lasers are considered a fire hazard and produce laser-generated air contaminants About 10% of all the fires are caused by lasers Source: ECRI Laser Use and Safety March 2011 84 Prevention of Fires During Laser Use Goal of the surgical fire prevention protocol includes Minimize or avoid oxidizer (such as oxygen) enriched atmosphere near the surgical site as 75% of the fires occur in oxygen enriched environments Safely manage the ignition source Safe manage the fuels Caution when performing laser surgery in the area of the perineal area such as hair removal surgery Physicians will pack the rectum with saline saturated gauze to prevent the unintentional expulsion of gases (methane gas is highly flammable) 85 Prevention of Fires During Laser Surgery Limit the laser output to the lowest clinically acceptable power density and pulse duration Test-fire the laser onto a safe surface (such as laser firebrick) before starting the surgical procedure to ensure that the aiming and therapeutic beams are properly aligned Place the laser in standby mode whenever it is not in active use Activate the laser only when the tip is under the surgeon’s direct vision Prevention of Fires During Laser Surgery Allow only the person using the laser to activate it Deactivate the laser and place it in standby mode before removing it from the surgical site Use surgical devices designed to minimize laser reflectance Never clamp laser fibers to drapes; clamping can break the fibers Use a laser backstop to reduce the likelihood of tissue injury distal to the surgical site Prevention of Fires During Laser Surgery Place wetted gauze or sponges adjacent to the tracheal tube cuff to protect the tube from laser damage, and keep them wet Wet any gauze or sponges used with uncuffed tracheal tubes to minimize leakage of gases into the oropharynx, and keep them wet Keep all moistening sponges, gauze, pledgets, and their strings moist throughout the procedure to render them ignition resistant Consider the use of towels soaked in saline or sterile water around the operative site to minimize the risk of igniting the towels So What’s In Your Policy? 89 Magnitude of the Problem Known fires •Unreported •Near misses ECRI Institute One of the richest sources Provide posters “Only You Can Prevent Surgical Fires” (info@ecri.org) Fighting Fires on the Surgical Patient Extinguishing Airway Fires Many materials have an associated cost unless subscriber to Healthcare Risk Control (HRC) MDSR (Medical Devise Safety Reports) Excellent tool to be aware of specific equipmentboth the risk and recommendations Free poster Offers an “Electrosurgery Checklist” Examples – Wrong gas in laparoscopic insufflator – Excessive illumination during surgical microscopy – Ignition of debris on active electrosurgical electrodes www.mdsr.ecri.org/summary/detail.aspx?doc_id=82 71&q= Medical Devise Safety Report Website http://www.mdsr.ecri.org/ 93 94 Electrosurgery Checklist 95 96 Can Search OR Fires 97 Fire Response Staff should know what to do in response to a fire If unexpected flash, unusual odors or unexpected smoke Surgery team needs to halt the procedure If a fire is confirmed then stop the flow of gases Rapidly remove the burning material Water or saline fore quenching the fire should be immediately available Use fire extinguisher if extensive, usually CO2 extinguisher Take care of the patient 98 Do Fire Drills Previously discussed the importance of doing fire drills Previous questions were provided that could be asked during the fire drill AORN fire safety tool kit also has a tool on hospital fire drill scenarios The scenarios have a corresponding set of roles and checklist Alert team of a fire, smoother or extinguish, push back table from field, remove burning material, assess for secondary fire, assess patient for injuries, complete incident report, assign person to family members, etc 99 Sample Scenarios to Use for Fire Drill 100 Surgical Fire 101 Fire Extinguishers If airway fire, remove the ET tube and have another member extinguish it and stop flow of gases Pour water or saline into the airway and care for the patient Review poster on fighting surgical fires before each surgical procedure Fire extinguisher is one of those things that OR staff seldom think about until it is needed OR fires occur in 3 possible locations In the airway Fires in or around the patient Fires elsewhere in the OR 102 https://www.ecri.org/surgical_fires 103 Fire Extinguishers Pull the pin and use sweeping motion at base of fire Be sure to select the right fire extinguisher This is decided by National Fire Protecting Agency (NFPA) code and state law Fires are categorized by NFPA as: A Fires involving ordinary materials like burning paper, lumber, cardboard, plastics, etc. B Fires involving flammable or combustible liquids such as gasoline, kerosene, and organic solvents C Fires involving energized electrical equipment such as appliances, electrical equipment, panel boxes, and power tools. 104 Fire Extinguishers Fires are categorized by NFPA as (continued): D Fires involving combustible metals such as magnesium, titanium, potassium, and sodium K Fires that occur in the kitchen The corresponding labeled fire extinguisher should be used For airway fires the oxidizer is usually the sole cause so turn the oxygen or nitrous oxide off Most ET tubes will not continue to burn without the oxygen or other oxizider 105 Fire Extinguishers PVC tubes melt and undergo a depolymerization but does sustain the burning process Silicone tubes disintegrate into an ash powder The tube should be removed and the oxygen or other oxidizer discontinued as previously mentioned Fires not extinguished by the removal of oxidizers can usually be smothered or doused with water Persistent fires can be eliminated with a carbon dioxide (CO2) extinguisher Make sure easy to use and readily available 106 Types of Fire Extinguishers APSF Winter 2011 Newsletter includes information on the types and also how they can cause medical problems A: Plain water which delivers a stream of water to cool the fire. These are prone to re-ignition and generally not safe to use in the OR because of all of the electrical equipment AC: Water mist which delivers a fine mist to cool the fire. This is safe for electrical fires because the mist does not allow an arc to be formed which could result in electrocution. Need adequate volume to put out the fire 107 108 Types of Fire Extinguishers BC: Dry chemical such as sodium or potassium bicarbonate or Co2 which smoothers the fire. Fires extinguished with CO2 are prone to re-ignition and can cause frostbite of the skin. The dry chemical dust of BC and ABC can cause respiratory irritation. The dust is difficult to remove from moist tissue ABC: Dry chemical and has ammonium phosphate 109 Types of Fire Extinguishers Halon and halotron: extinguishes the fire by replacing oxygen and cooling and safe for electronic devices Sensitizes myocardium to catecholamines and can cause lethal arrhythmias Halon is being phased out because of ozone issues FE-36 (HFC-23fa): is a clean agent, non-toxic, ozone safe and has no residue but is more expensive D and K: are only kept in locations where appropriated and highly specific and would be used in places like the kitchen 110 Placement of Extinguisher Should be consistent with the local fire code and NFPA guidelines NFPA recommends there should be one within 75 feet of any working area Should be mounted in a consistent location such as near main door and on the left One hospital has a CO2 extinguisher in every OR room and with the laser cart A rated extinguisher in the hall cabinets AC rated water mist for the MRI suite and halon and CO2 in the fire hose cabinet 111 Fire Extinguishers 112 ECRI Institute Surgical Fires 113 Competency Hospital should make sure staff are evaluated on their competency for fire safety AORN has a perioperative RN Performance Evaluation Tool for fire safety AORN members have free access to their fire safety toolkit Circulating nurse Reports and documents fire risk assessment Manages fuel source by preventing pooling of prep solutions, removes prep soaked linen, provides anesthesia a laser resistant coated ET tube 114 Competency Circulating nurse manages ignition sources Keeps active electrode cords free of coils off of sterile field Places the electrosurgical unit (ESU) dispersive pad on a large muscle close to the surgical site Inspects ESU or laser electrical cords and plugs for integrity Uses only connectors or adapters to connect to the ESU which fit securely Sets the power setting as low as possible to achieve the result Places light source in standby mode or turns it off when cable is not in active use etc. 115 AORN Competency Tool 116 Competency Circulating nurse manages oxidizers Use a pulse ox to determine oxygen level Titrates oxygen to lowest % to support patient’s needs Configures drapes to help prevent oxygen accumulation if mask or nasal cannula is used, beneath the drapes Stops oxygen for 1 minute before using laser or electrosurgery for head, neck, or upper chest when requested Scrub nurse competencies follow 117 AORN Perioperative Evaluation Tool 118 AORN Fire Safety Toolkit http://www.aorn.org/Pr acticeResources/Tool Kits/ 119 AORN Fire Safety Resources 120 Remember the Major Guideline Changes Remember the major changes in clinical practice for face, neck, head, or upper chest surgery; Use only air for open delivery to the face, provided that a spontaneously breathing sedated patient can maintain his or her blood oxygen saturation without extra oxygen Secure the airway by using a laryngeal mask airway or tracheal tube if the patient cannot maintain safe blood oxygen saturation without supplemental oxygen, so that oxygen-enriched gases do not vent under the surgical drapes 121 Remember the Major Guideline Changes Discontinue the traditional practice of open delivery of 100% oxygen with limited exceptions –Exceptions might include when the patient needs to speak during procedure when oxygen is delivered by a cannula or mask to maintain adequate oxygen saturation –Might include carotid artery surgery, neurosurgery, and some pacemaker implantations 122 In Summary Surgical fires are a preventable hazard Success requires understanding risks & promoting perioperative communication among all members of the team Educate staff about OR fire safety Have a plan to extinguish fire and protect patient and staff Provide review of fire safety at least annually Conduct regular drills In Summary Ensure staff are competent in fire safety Surgical Team Communication is vital and include summary in time out Enriched O2 & N20 vastly increase flammability of drapes, plastics & hair be aware of trapping under drapes Delay draping until preps are completely dry Fiber optics can start fires complete cable connections before activating source Moisten sponges to make ignition resistant in oropharyngeal & pulmonary cases In Summary If O2 & N20 are administered during oral or ophthalmic surgery make hair near operative site nonflammable by thoroughly coating with water-soluble surgical lubricating jelly Position safety holsters for electrocautery or active electrode in a convenient location and mandate use During oropharyngeal surgery scavenge deep within oropharynx with separate suction to catch leaking O2 & N20 Soak gauze or sponges used with uncuffed tracheal tubes to minimize gas leakage into oropharynx (keep moistened) In Summary Keep tip of any electrosurgical equipment in plain view Eliminate the traditional practice of open delivery of 100% oxygen during sedation Securing the airway is recommended if the patient requires an increased oxygen concentration Inspect every cable and electrical supply cord before Update P&P on an annual basis and make sure staff is aware of policy In Summary Keep abreast of current literature to be aware of newly discovered sources for fuel/ignition Thoroughly analyze any incidents including near misses Report all fires to the fire marshal Be aware of the position statements of organizations like AORN and ASA The End Questions Sue Dill Calloway RN, Esq AD, BA, BSN, MSN, JD CPHRM President Patient Safety and Health Care Consulting 5447 Fawnbrook Lane Dublin, Ohio 43017 614 791-1468 sdill1@columbus.rr.com 128 Resources 129 American College of Surgeon http://www.facs.org/about/committees/cpc/ope r0897.html 130 ASHE Organization associated with AHA Material covered by other resources Minimizing Fuel Risks during skin prep Be aware and alert to the flammability of alcohol-based preps Avoid pooling or wicking of liquid preps Allow liquid to fully dry before draping Use a properly applied drape (no gas communication channels Other Factors Increasing Risk Only metal ones are nonflammable Endotracheal tubes most made of flammable materials like silicone, rubber, and plastic Most made of flammable materials like silicone, rubber, and plastic Only metal ones are nonflammable Increased use of disposable drapes Less expensive & more water resistant but burn more readily – Once ignited burn with alarming speed ASHE Website http://www.ashe.org/ 133 134 SurgicalFire.org 135 Resources Petersen C, ed. Perioperative Nursing Data Set. 3rd ed. Denver, CO: AORN, Inc; 2010. Recommended practices for electrosurgery. In: Perioperative Standards and Recommended Practices. Denver, CO: AORN, Inc; 2010:105-125. “Recommended practices for endoscopic minimally invasive surgery.” In Standards, Recommended Practices, and Guidelines. Denver, Co: AORN, Inc; 2010:139-174. “Recommended practices for laser safety in practice settings.” In Standards, Recommended Practices, and Guidelines. Denver, Co: AORN, Inc; 2010:133-138. 136 Resources Caplan RA, et al. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:786-801 National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 10, Standard for portable fire extinguishers. 2011. Chapter 5.2 American National Standards Institute. American national standard for safe use of lasers in health care facilities. ANSI Z136.3 – 2005 C.9.35. Appendix: 52. 2005. 137 Resources ECRI. New clinical guide to surgical fire prevention. Health Devices. 2009;38(10):314-332. Allen, G. “Evidence for Practice. Laser ignition of surgical drape materials.” AORN J. 2004;80:577578. Andersen, K. “Safe use of lasers in the operating room: what perioperative nurses should know.” AORN J. 2004;79;171-178. Ball, Kay. Lasers: The Perioperative Challenge. Denver, Co: AORN, Inc; 2004. 138 Resources Ossoff RH, Duncavage JA, Eisenman TS, Karlan MS. Comparison of tracheal damage from laserignited endotracheal tube fires. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1983;92:333-336. DuPont. DuPont fire extinguishants: DuPont FE-36 use as a fire suppressant in surgical operating rooms. White Paper. Jan 2005. Available at: http://www2.dupont.com/FE/en_US/products/fe36.ht ml. Accessed January 6, 2011. 139 Resources Amerex Corporation. ABC dry chemical fire extinguishant. Trussville, AL, June 2010. Available at: http://www. amerex-fire.com/msds/msd/2. Accessed January 6, 2011. H3R Aviation. Halon 1211. Larkspur, CA, August 18, 2009. Available at: http://www.h3rcleanagents.com/downloads/Halon1211-Clean-Agents-MSDS.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2011. National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 10, Standard for portable fire extinguishers. 2010. Table 6.2.1.1. 140 Resources Beyea, S.C. “Preventing fires in the OR. AORN J. 2003;78:664-666. Flowers, J. “Code red in the OR—implementing an OR fire drill.” AORN J. 2004;79:797-805. Hogan, C. “Responding to a Fire at a Pediatric Hospital.” AORN J. 2002;75:793-800 Salmon, L. “Fire in the OR—prevention and preparedness.” AORN J. 2004;80:41-52. 141 Resources McCarthy, PM, Gaucher, KA. “Fire in the OR— developing a fire safety plan.” AORN J. 2004;79:587-594. Smith, C. “Surgical fires—learn not to burn.” AORN J. 2004;80:23-34. Stewart, D. “Fire and life safety for surgical services: What’s new and what to review.” Surgical Services Management. April 2003; 26-31. 142