Management of Surgical Fires

advertisement

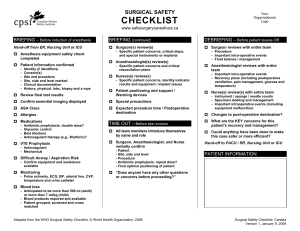

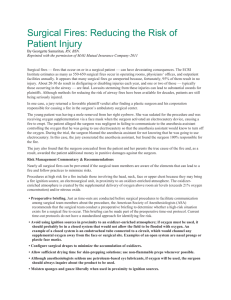

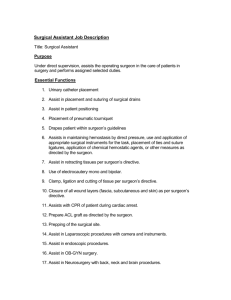

Management of Surgical Fires An estimated 550 to 650 surgical fires occur in the United States per year, some causing serious injury, disfigurement and even death (FDA, May, 22, 2013).To start a fire, you must have a heat source, oxidizers and a fuel source. This is known as the “fire triangle.” A high risk procedure is defined as one in which an ignition source (e.g., electrocautery) can come in close proximity to an oxidizer-enriched (e.g., oxygen or nitrous oxide) atmosphere. Every member of the OR/Procedure Team must know their role in management of the fire. The anesthesiologist must protect the airway, the surgeon/physician must protect the surgical/procedural site and the rest of the OR Team must follow their fire plan for obtaining or having immediately available fire extinguishing equipment/supplies and executing safe evacuation of the patient. Prevention: Actions to take to prevent OR fires include minimizing or avoiding an oxidizer-enriched atmosphere near the surgical site, safely managing ignition sources and safely managing fuels. Other important steps to minimize risks include allowing flammable skin preps to completely dry, configuring surgical drapes to prevent oxygen from accumulating under them and moistening sponges when using them near an ignition source (especially in or near an airway). For High-Risk Procedures: The Anesthesiologist should collaborate with the Procedure Team prior to beginning the procedure, notify the surgeon when an ignition source is in proximity to an oxidizerenriched atmosphere or if concentration of oxygen has been increased, keep the delivery of oxygen to the patient as low as clinically possible when a ignition source is in proximity, avoid the use of nitrous oxide in settings that are considered high-risk for fire and use saline tinted with methylene blue to fill the tracheal cuff instead of air. For Surgery Inside the Airway: Follow these recommendations to prevent surgical fires during surgery inside an airway - use a cuffed tracheal tube (if medically feasible), advise the surgeon not to enter the airway with an ignition source, assure that the surgeon provides adequate warning to allow the concentration of oxygen to be reduced before the trachea is entered. The surgeon should ask the anesthesiologist to report the time they believe is needed to decrease the oxygen or nitrous oxide concentration before using an ignition source. Management of OR Fires: Steps to managing an OR fire include, recognizing the early signs of fire (“pop or foomp” sound, unusual odors, unexpected smoke or heat, discoloration of drapes or breathing circuit, unexpected movement of drapes or unexpected flash or flame); immediately halt the procedure; make appropriate attempts to distinguish the fire; follow your evacuation protocol as soon as medically appropriate and deliver post-fire care to the patient. For every case, the anesthesiologist should participate with the entire OR Team in assessing and determining whether a high-risk situation exists. If it is determined to be a high-risk situation, the team should jointly agree on how a fire will be prevented and managed. References: i Preventing Surgical Fires: Collaborating to Reduce Preventable Harm. FDA. May 22, 2013. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/SafeUseInitiative/PreventingsurgicalFires/default.htm Practice Advisory for the Prevention and Management of Operating Room Fires: An Updated Report by the American society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology, V.118.No 2. pp 118. Feb 2013.