Nash solution of (.75* .8 =) .6

advertisement

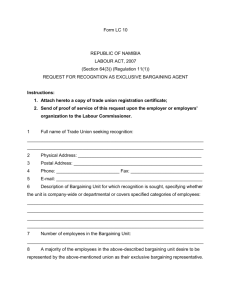

George Mason School of Law Contracts II Unconscionability Not to be shared © F.H. Buckley fbuckley@gmu.edu 1 Forms of Unconsionability UCC § 2-302. Unconscionable Contract or Clause (1) If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result. 2 Forms of Unconsionability UCC § 2-302. Unconscionable Contract or Clause (1) If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result. 3 Forms of Unconsionability UCC § 2-302. Unconscionable Contract or Clause (1) If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result. 4 Forms of Unconsionability Substantive Unconscionability The “just price” doctrine Procedural Unconscionability “bargaining naughtiness” 5 Was secured lending in Walker-Thomas a problem of substantive unconscionability? 6 Substantive Unconscionability Usury legislation Barriers to personal property security interests in consumer goods in Article 9 7 Procedural Unconscionability Was Mrs. William’s consent tainted in some way, short of actual duress or fraud? 8 Why might a consumer agree to “excessive” interest rates? Lack of capacity? Something like Duress? Something like Fraud: An informational problem? Moral hazard? Signaling? 9 Lloyds Bank v. Bundy Lack of capacity? Duress? An informational problem? 10 Lloyds Bank v. Bundy 11 Lloyds Bank v. Bundy What did the bank manager (Head) do that was wrong? Did he owe any duties to the borrower (Michael)? Did he owe any duties to Herbert? 12 Denning’s Categories “Duress of goods”: Inequality of bargaining power Hochman at 407 Austin v. Loral 13 Denning’s Categories The expectant heir: One-and-twenty Wealth, my lad, was made to wander, Let it wander as it will; Call the jockey, call the pander, Bid them come and take their fill. 20 When the bonny blade carouses, Pockets full, and spirits high— What are acres? What are houses? Only dirt, or wet or dry. Should the guardian friend or mother Tell the woes of wilful waste, Scorn their counsel, scorn their pother;— You can hang or drown at last! Samuel Johnson 14 25 Denning’s Categories Undue influence 15 Fiduciary relationship Employer exploiting employee D&C Builders v. Rees D&C accepts £300 as full payment of a debt of £482 when it desperately needed money to fend off bankruptcy, and Rees knew this Denning’s Categories Salvage Agreements Post v. Jones 16 A General Principle of Inequality of Bargaining Power? “English law gives relief to one who, without independent advice, enters into a contract or transfers property for a consideration which is grossly inadequate, when his bargaining power is grievously impaired by reason of his own needs or desires, or by his own ignorance or infirmity, coupled with undue influences or pressures brought to bear on him by or for the benefit of the other.” 17 Why look at an English case? Maryland is a foreign jurisdiction to Virginians… 18 Why look at an English case? The importance of style: Broadchalke is one of the most pleasing villages in England. Old Herbert Bundy was a farmer there. His home was at Yew Tree Farm. It went back for 300 years. His family had been there for generations. It was his only asset. But he did a very foolish thing. He mortgaged it to the bank. Up to the very hilt. 19 Why look at an English case? The Analogic Imagination: Gathering all together, I would suggest that through all these instances there runs a single thread. They rest on "inequality of bargaining power". 20 Why might a consumer agree to “excessive” interest rates? An informational problem Thornborrow v. Whitacre, 92 Eng.Rep. 270 (1705): W. borrows £5 and in return promises to pay two grains of rye-corn in the first week, four in the second, eight in the third, and so on for a year. The court refused to enforce the contract when it appeared that there was not enough grain in the whole world to satisfy this. Was Lloyd’s Bank such as case? Or Williams v. Walker-Thomas 21 Why might a consumer agree to “excessive” interest rates? A moral hazard problem What does bankruptcy law and the welfare safety net do to our investment decisions? 22 Moral Hazard A range of outcomes associated with an investment opportunity 23 Moral Hazard How is one’s economic calculus affected if costs are curtailed at 0 on the left side of the curve? 24 Moral Hazard In that case, it’s all upside: Heads I win, tails you lose 25 Moral Hazard: We make risker choices when we don’t pay for downsides Thank God I have insurance! 26 Moral Hazard Do traffic signals cause accidents? 27 How to reduce speed levels… 28 Moral Hazard So a consumer might be more willing to court default with a high risk loan because of the welfare safety net. 29 Moral Hazard So what’s “excessive”? Is there such a thing as “excessive risk aversion” 30 Why might a consumer agree to “excessive” interest rates? Signalling 31 Signalling Two borrowers approach a lender. One is high risk, the other low risk. The borrowers know their quality but the lender cannot tell them apart. How can he distinguish them? 32 Signalling Two borrowers approach a lender. One is high risk, the other low risk. The borrowers know their quality but the lender cannot tell them apart. How can he distinguish them? Assume that default is costly for both borrowers. However, the low risk borrower has a lower probability of default and a lower cost of default 33 Signalling A signalling equilibria if a “nonmimicry” constraint By their willingness to accept the cost of a high interest loan one can tell them apart and they don’t have an incentive to switch 34 Signalling Separating equilibrium: Benefit > Cost*High Quality Borrower Benefit < Cost*Low Quality Borrower *Cost is a function of the probability of default 35 Signalling Signalling doesn’t work if a pooling equilibrium Low quality can mimic high quality 36 Signalling Pooling equilibrium Benefit > CostHigh Quality Borrower Benefit > CostLow Quality Borrower 37 Cheap Talk as a Pooling Equilibrium Hobbes: He which performeth first doth but betray himself to his enemy. 38 Signalling A separating equilibrium if the low risk borrower is unwilling to accept a penalty on default? 39 Just what was wrong in WalkerThomas? 40 Capacity? Poverty? Nature of goods? Welfare grants? Kids? Seabrook: 502 Apartment to be ready three months later Unfinished Apartment Building 41 Seabrook How long was the delay? 42 Seabrook Do you think counsel for Commuter Housing was trying to pull a fast one in clauses 33 and 19? 43 Seabrook Do you think counsel for Commuter Housing was trying to pull a fast one in clauses 33 and 19? What did the court say was missing? 44 Seabrook Do you think counsel for Commuter Housing was trying to pull a fast one in clauses 33 and 19? What did the court say was missing? Why not strike the clause and imply a reasonable time (and might that be four months? 45 Seabrook Can you articulate the legal principle behind the case? 46 Seabrook Can you articulate the legal principle behind the case? “absence of meaningful choice” “Once the consumer enters to merchant’s trap … he is caught in a web” “The concept of laissez-faire ... Has no place in our enlightened society” 47 Here’s one legal principle … 48 Seabrook Did the lessee have “no choice but to sign an unconscionable lease agreement” “does not have the option of shopping around” 49 Seabrook Did the lessee have “no choice but to sign an unconscionable lease agreement” Were there other rental properties in NYC? 50 Seabrook Did the lessee have “no choice but to sign an unconscionable lease agreement” Were there other rental properties in NYC? If they were hard to get, might rent control have had something to do with this? 51 Seabrook Just what was unconscionable? Did the lessee know that the building was not completed when he signed the lease? 52 Seabrook Just what was unconscionable? Do you think the lessee might have considered that there was a possibility that the building would not be completed three months later? 53 Seabrook Just what was unconscionable? Do you think the lessee might have considered that there was a possibility that the building would not be completed three months later? What do you think he would have expected to happen in that case? 54 Seabrook If you thought that the lessor should have provided for a maximum period, is that the hindsight bias at work? 55 Henningsen 1960 Plymouth Look: Fins!!! 56 Henningsen 1960 Plymouth … in two-tone! 57 Henningsen With a push-button tranmission! 58 And today? 2012 Chevrolet Spark 59 Henningsen 1960 Plymouth 60 Henningsen And what did they do with their car!! 61 Henningsen Are exemption clauses intrinsically suspect? 62 Henningsen A right to dicker? $3.99? I think we can do better, don’t you? “No bargaining is engaged with respect to it” 63 Henningsen Why only a three months warranty on parts? 64 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? Look at the list on 506 65 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? 66 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? If so, why do you think that was? 67 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? Is a similarity in prices or terms across a market evidence of cartelization or of a competitive market? 68 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? Is a similarity in prices or terms across a market evidence of cartelization? Would you expect to a monopolist exploit his clout with prices and not terms? 69 Henningsen Would you expect to a monopolist exploit his clout with prices and not terms? Is it different if the information about warranties is difficult to understand? 70 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? Is a similarity in prices or terms across a market evidence of cartelization? Does competition as to terms assume that all consumers screen? Free riding? 71 Henningsen Were the Big Three immune from competition? Is a similarity in prices or terms across a market evidence of cartelization? Does competition as to terms assume that all consumers screen? Suppose you heard that one firm had an extortionate contract? 72 Litigation or Regulation? OIRA’s Mandate: Federal agencies should promulgate only such regulations as are required by law, are necessary to interpret the law, or are made necessary by compelling public need, such as material failures of private markets to protect or improve the health and safety of the public, the environment, or the well-being of the American people. In deciding whether and how to regulate, agencies should assess all costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives, including the alternative of not regulating. 73 Federal Arbitration Act of 1925 Partial preemption of state law Rent-a-Center v. Jackson at 513 74 Understanding our intuitions about fairness in bargaining Procedural Fairness Substantive Fairness Distributive Justice 75 Game Theory and the Revival of Substantive Unconscionability The game theorist’s revival of cardinal utility 76 The two-person bargaining game The Edgeworth Box Function provided a bargaining model based on ordinal utility (indifference curves) 77 Recall the Contract Curve Indifference curve in commodity space Bess A E D F B G C Mary 78 78 The two-person bargaining game The Edgeworth Box Function teaches us that bargaining is a non-zero sum game But at the heart of the bargaining game is a zero-sum game 79 Blowing up the bargaining lens A C • • F• •G B• 80 80 Blowing up the bargaining lens A C • • F• •G B• 81 81 At C Mary is much better off than at A, and Bess is neither better nor worse off Blowing up the bargaining lens A C • • F• •G B• At B Bess is much better off than at A, and Mary is neither better nor worse off 82 82 Recall the Contract Curve Indifference curve in commodity space Bess A E D F B G C Mary 83 83 Blowing up the bargaining lens A C • • F• •G B• 84 84 At G both parties are better off than at A Recall the Contract Curve Indifference curve in commodity space Bess A E D F B G C Mary 85 85 Does unconscionability have anything to do with how bargaining gains are divided? A C • • F• •G Is your intuition that G is in some sense fairer than B or C? B• 86 86 Does unconscionability have anything to do with how bargaining gains are divided? A C • • F• •G B• But as we are talking about ordinal utility, it is not meaningful to speak of how much better off someone is at G relative to B or C 87 87 Does unconscionability have anything to do with how bargaining gains are divided? A C • • F• •G B• To do so, we would need to move from ordinal to cardinal utility 88 88 Ordinal and Cardinal Utility Ordinal numbers: First, second, third… Cardinal numbers: 1, 2, 3 … 89 Ordinal and Cardinal Utility The Edgeworth Box Function provided a bargaining model based on ordinal utility (indifference curves) However, prior to the ordinalist revolution of the 1930s, economists thought of utility in a cardinal way 90 Cardinal utility Act always to increase the greatest happiness of the greatest number 91 Are you a cardinalist? Yes, if you think interpersonal utility comparisons are meaningful 92 Are you a cardinalist? You are charged with designing a country’s welfare policy. Should wealth transfers be from rich to poor or the other way around? 93 Are you a cardinalist? You are charged with designing a country’s welfare policy. Should wealth transfers be from rich to poor or the Blimey, this social justice other way around? business is trickier than I thought! 94 Cardinalists assume we can measure utility levels We move from commodity to utility space A G C 95 95 Cardinalists assume we can measure utility levels The units of measurement are now in “utils,” not commodities A G C 96 96 Let’s suppose we can measure Mary’s utility levels Utility space A G C Cardinal, not ordinal utility 97 97 And suppose we can do the same for Bess B Bess’s utility G' A Utility Space G C 98 98 Mary’s utility To simplify we normalize the utility functions of both from 0 to 1.0 1.0 Bess 0 1.0 Mary 99 99 We can then represent the contract curve in utility space B BC is concave (bends outward) because we assume that joint utility is maximized when gains are shared Bess A Mary 100 100 C The Presolution B Every point on BC represents the “presolution” to the game: they are feasible and efficient Bess A Mary 101 101 C The Solution The “solution” to the two-person bargaining game picks one point on the contract curve 1.0 Bess 0 1.0 Mary 102 102 The Nash Solution 1.0 Nash solution of (.75* .8 =) .6 • Bess Nash maximizes the product of the utility gains Mary 0 1.0 Howard Raiffa, The Art and Science of Negotiation (1982) 103 103 The hard bargainer doesn’t seek the Nash Solution 1.0 • Bess Mary insists on a payoff of .95 0 Mary 104 104 .95 1.0 Do we have fairness intuitions which think this unfair? 1.0 • Bess Mary insists on a payoff of .95 0 Mary 105 105 .95 1.0 The ultimatum game We have $1,000 to divide between us. I first decide how the money is to divided. 106 106 The ultimatum game We have $1,000 to divide between us. I first decide how the money is to divided. In the second stage you decide whether or not to accept the split I propose. 107 107 The ultimatum game We have $1,000 to divide between us. I first decide how the money is to divided. In the second stage you decide whether or not to accept the split I propose. If you accept the split we both take our respective shares. If you reject the split neither of us get anything. 108 108 The ultimatum game In the first round I choose $950, leaving you $50 Take it or leave it? 109 109 The ultimatum game Player 1 Player 2 Accept 500, 500 Fair Unfair Player 2 Reject 0, 0 Accept 950, 50 Is the unfair solution Paretian? 110 Reject 0, 0 Do we have built-in fairness constraints? You see that Safeway refuses to charge a premium for a shovel during a snow storm Is it being irrational? 111 111 Now back to the ultimatum game Suppose we refused to enforce bargains that appear wholly onesided? This would result in an efficiency loss. But would chilling the hard bargainers result in a greater number or bargains, and a net efficiency gain? 112 112 Last fairness question: Distributional Justice 113 Distributional Justice: Who says it was fair to start at point A? Bess A E D F B G C Mary 114 114 Distributional Justice: What if we started at point E? Bess A E D F B G C Mary 115 115