When looking at my bachelor thesis as a whole I believe it

advertisement

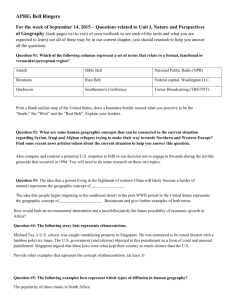

S T A N D A R D FORSIDE TIL EKSAMENSOPGAVER Udfyldes af den/de studerende Prøvens form (sæt kryds): Projekt Synopsis X Portfolio Speciale Skriftlig hjemmeopgave Uddannelsens navn SIV Engelsk Semester Prøvens navn (i studieordningen) 6. semester Navn(e) og fødselsdato(er) Navn Fødselsdato Nauja Joeslsen 13.04.85 Afleveringsdato Projekttitel/Synopsistitel/Specialetitel 28/5-2014 Amish I henhold til studieordningen må 72.000 opgaven i alt maks. fylde antal tegn Den afleverede opgave fylder (antal tegn med mellemrum i den 44.854 afleverede opgave) (indholdfortegnelse, litteraturliste og bilag medregnes ikke)* Vejleder Richard Madsen (projekt/synopsis/speciale) Jeg/vi bekræfter hermed, at dette er mit/vores originale arbejde, og at jeg/vi alene er ansvarlig(e) for indholdet. Alle anvendte referencer er tydeligt anført. Jeg/Vi er informeret om, at plagiering ikke er lovligt og medfører sanktioner. Regler om disciplinære foranstaltninger over for studerende ved Aalborg Universitet (plagiatregler): http://plagiat.aau.dk/GetAsset.action?contentId=4117331&assetId=4117338 Dato og underskrift 28/5-2014 1 Resume I denne bachelor afhandling vil jeg forsøge at belyse Amish folket og deres samfund. Mit hovedfokus vil være på de unge og deres ”rumspringa” periode, ”rumspringa” betyder noget i retningen af ”at løbe rundt”, de unge har i denne periode mulighed for at udforske og opleve det amerikanske samfund, Amish referer selv til det amerikanske samfund som det engelske samfund. Derudover, vil mit fokus være at belyse hvordan Amish den dag i dag formår at blive ved med at vokse og hvorfor ikke flere bliver tiltrukket af den engelske kultur og deres måde at leve et ”simplere” liv på. Min problemformulering lyder som følgende: ”Amish eksistere som et parallel samfund til det yderst globaliseret amerikanske samfund, hvorfor er de ikke tiltrukket af den amerikanske livsstil, i blandt Amish refereret til som det ”engelske samfund”, og hvorfor vokser Amish samfundet hurtigere end nogensinde?” Jeg vil i min introduktion starte med at tage udgangspunkt i hvordan Amish er opstået i Europa, for at få en overordnet ide om deres oprindelse og hvorfor de er opstået. Hernæst vil jeg i mit metode afsnit give en kort redegørelse for hvordan jeg vil behandle min empiri, samt en redegørelse for hvordan jeg har tænkt mig at gribe opgaven an. Jeg vil yderligere præsentere mit valg af videnskabsteori: socialkonstruktivisme, teoretikere og de termer jeg vil benytte til at analysere mit empiri: Clifford Geertz - webs of significances, ethos, world view og delvist symbol samt Erik H. Erikson - identitet. Jeg har valgt at basere min opgave på nogle tekster, som jeg finder valide og relevante i forhold til min problemformulering. Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen har skrevet generelt om Amish og beskriver kort og præcist om deres traditioner, deres modersmål og hvad deres holdninger er til den/det omkring liggende verden/samfund. Tom Shachtman’s bog: ”Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish” er en bog som yderst detaljeret beskriver de unge i Amish samfundet og deres “rumspringa” periode, Shachtman har fået lov til at komme helt tæt på de unge og har skrevet bogen på baggrund af 400 timers interviews med disse. Til sidst har jeg Thomas J. Meyers’ rapport “The Old Order Amish: To Remain In The Faith or To Leave”, som både oplyser nogle tal og statistikker på de Amish som beslutter sig for at forlade samfundet, men som samtidig også kommer med forslag til og begrunder hvorfor de vælger som de gør. I min analyse benytter jeg teoretikernes termer til at analysere mig frem til de mulige svar der er på min problemformulering, altså hvilke årsager der ligger bag ved de unges valg når de skal vælge om de vil forblive Amish eller om de vil forlade Amish, f.eks. 2 skriver Meyers at: “En gennemsnitlig Amish familie i Elkhart-LaGrange bosættelsen får 7,39, hvor en stor gruppe af “afhopperne” er det første, andet eller tredje barn, sammenlignet med det fjerde til det syvende barn.” (Meyers, 1992:7). I min analyse vil jeg videre kunne fastslå at, “Jeg mener Amish er mere afhængig af deres børns hjælp pga. deres måde at leve på, deres “webs of significance”, “ethos” and “world view” tilsammen (…)”. Til sidst i min konklusion konkluderer jeg at, ”Et andet faktum er at en familie i gennemsnit får 7,39 børn, som udligner det antal som beslutter sig for at forlade samfundet (…)”. 3 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Problem Statement ..........................................................................................................................6 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................7 Empirical Data ...................................................................................................................................8 “Amish: The Traditions of the Amish Community” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen ........ 8 “Amish: Language of the Amish Community” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen ................... 8 “Amish: Why the Amish Do Not Use Electricity” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen .............. 9 ”Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish” by Tom Shachtman ................................................... 9 “The Old Order Amish: To Remain In The Faith or To Leave” by Thomas J. Meyers........ 11 Theory ............................................................................................................................................... 13 Clifford Geertz ........................................................................................................................................... 13 Reflection of the Theory ........................................................................................................................ 15 Erik H. Erikson .......................................................................................................................................... 15 Reflection of the Theory ........................................................................................................................ 16 Theory of Science ..................................................................................................................................... 16 Analysis ............................................................................................................................................. 17 Discussion ........................................................................................................................................ 22 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 23 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................... 24 4 Introduction Since the first adult baptisms took place in 1525 in Switzerland (Nolt, 1992:10), the Anabaptists have survived opposition, resistance and persecution. By choosing the adult baptism, the Anabaptists dissociated themselves from the Catholics, with a wish to separate state (politics) and church (religion) – which at that time was closely connected with one another (Nolt, 1992:9). One of their main arguments for practicing the adult baptism was that an infant or a child was “not yet old enough to understand Christ’s call of discipleship” (Nolt, 199:10). The Anabaptists considered themselves to be peaceful, humble, simple and nonresistant, beside they lived a very simple live, in accordance to the bible. As mentioned, the Anabaptists were persecuted by the state church and when caught they were jailed, tortured, burned, killed or sold as galley slaves to row themselves to death on the Mediterranean (Nolt, 1992:11). These persecutions reinforced their idea of the rest of the world to be brutal, arrogant, proud and wealthy. The Amish considered themselves and their values to be the opposite from the rest of the world’s values - the world was cruel and the church was suffering. (Nolt, 1992:11). At this time the Anabaptists were mainly situated throughout Switzerland, southern Germany, the Austrian Tyrol and Moravia, they later arrived in northern Germany and the Netherlands (Nolt, 1992:11). Because of the wide spread, some of the leaders felt an urge to define what held them together and lay the foundation of church life and practice: “We have been united to stand fast in the Lord (…) as obedient children of God, sons and daughters, who have been and shall be separated from the world in all that we do and leave undone, and … completely at peace.” (Nolt, 1992:13). In 1534, Anabaptists in Northern Europe violently conquered Münster with the purpose of creating an Anabaptist church-state, doing the exact same to those who would not be baptized as an adult, as was done to the Anabaptists persecuted in the South. The Anabaptist church-state did not last long and within a year, a Catholic/Protestant army crushed the Münster conquest. Sadly, the violent reputation affected the nonviolent Anabaptist and they were all “measured by the same yardstick” - all Anabaptists were now considered violent and militant revolutionaries making the persecutions harsher. (Nolt, 1992:14-15). In 1536, a Dutch Catholic priest named Menno Simons, who secretly had sympathized with the Anabaptists, openly joined the nonviolent Anabaptist group. He spent the next 5 25 years rebuilding the nonviolent Anabaptist community across northern Europe and his impact was so significant, that the northern Anabaptists a few decades later were called “Mennonites” (Nolt, 1992:15). In order to avoid some European theologians and church reformers, claiming the church was only “spiritual” and “other-worldly”, affected the Anabaptists’ belief; the Mennonites imposed severe consequences in case of sin or members leaving the church by shunning them (Nolt, 1992:15). In the years to follow, especially in the southern parts of Europe, the Anabaptist Mennonites seemed to have become more open towards their family members who, because of the persecutions, had decided to return to the state church and therefore should be shunned. These family members epithet with the “True-Hearted”, since they in some ways managed to communicate the Mennonites’ political voice, protected them from the persecutions and attempted to help out with daily chores, were not shunned as the regulations dictated. Therefore in 1693, Jakob Ammann called for a church reform, which met lot of disagreement among the Mennonites who wished to maintain a bond to their family members and saw the benefits hereof; he therefore founded his own disciplined church – the Amish. (Nolt, 1992:23-32). Since the first Amish settled in America in 1736, they have been able to preserve their values and way of life. Despite the technological development, the social and societal development and cultural pressure they have been capable of standing together and live by the rules they have lived by since the early 1500. Problem Statement The Amish exist as a parallel community to the highly globalized society in the US, why are they not attracted by the “American lifestyle”, among the Amish referred to as the “English lifestyle”, and why is the Amish community growing faster than ever? 6 Methodology In this paragraph I will shortly account for how I will answer my problem statement. I know that the methodological choices I have made will shape the outcome of my bachelor thesis. I know for a fact that the Amish community is very closed to the outside world and therefore I have had to make several considerations of how to approach the subject. I have chosen social constructivism as my theory of science. This philosophical discipline as an overall theory, I believe, will help me create a better understanding of the Amish since their belief, values, norms, ethics and moral are socially constructed. I have chosen two theoreticians who I believe will complement each other when analyzing my empirical data and in the attempt of answering my problem statement. Clifford Geertz and Erik H. Erikson, both acknowledged and well-reputed within the fields of culture and identity development. They will provide terms that will make me able to explain, clarify and concretize the challenges and state of minds the young Amish go through. I have chosen to only use the relevant terms from their theories that I believe will make me able to answer my problem statement. Geertz’s theory: “webs of significances”, “ethos”, “world view” and, partly, “symbol” and the relevant term from Erikson’s theory: “identity”. The data I will be analyzing is secondary data. I have chosen to focus on the adolescents and have chosen to omit the adults leaving the Amish community. I am aware of the fact that I might be generalizing the Amish communities, but it has been necessary in order for me to make this subject manageable. It might not be necessary for me to state, but it would be impossible for me to make interviews or questionnaires with the Amish. 7 Empirical Data This paragraph contains a short introduction to the books and texts from which the analysis of this bachelor thesis is based on. “Amish: The Traditions of the Amish Community” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen The Amish use the Bible as their guideline of life. They believe the Bible is God’s words and that they as Christians are to live as brothers, that the church has to be independent of the state, and that they will go to heaven by believing in their Savior Jesus. The philosophy of life the Amish believe in is called “Gelassenheit”, basically meaning humility and repression; by living in accordance to the “Gelassenheit” they believe they bring God joy and honor. This term contains a number of specific meanings: “Humility towards God’s will, respecting others, a simple life, obedience, thrift and non-violent behavior.” Therefore, “Gelassenheit” is a social process where the energy of the individual will be used to benefit the community in the best possible way. The Amish live according to the “Ordnung”, which is an unwritten guideline, rooting from the “Gelassenheit”, for how to live a correct Amish life. Containing rules and regulations; the “Ordnung” provides the foundation of any Amish community. According to Jørgensen, the “Ordnung” is not committed to paper but all Amish are expected to live and behave in accordance to it. The Amish children will learn about the “Ordnung” by hearing their parents and other adults talking about and discussing it. It is by observing their parents the Amish children will learn how to behave and how to live the Amish life. I have chosen this paragraph because it short and precisely describes the terms “Gelassenheit” and “Ordnung”, the basic guidelines for the Amish way of life in all Amish communities. The definitions herein are supported by other texts I have read, which validates this paragraph “Amish: Language of the Amish Community” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen According to Jørgensen, the spoken language within the family and the Amish community is Pennsylvania Dutch. The language is primarily oral spoken and the Amish children learn to write, read and speak English in school – all Amish adults speak fluently American English. 8 I have chosen this paragraph because it short and precisely states the language of the Amish; I believe their language is an important aspect of their identity and community. The statement herein is supported by other texts I have read, which validates this paragraph “Amish: Why the Amish Do Not Use Electricity” by Nanna Dissing Bay Jørgensen According to Jørgensen, the Amish believe the Bible states that they shall not accommodate this world. Therefore, their way of life becomes an intentional attempt to separate from the rest of the world and be self-sufficient. They believe that easy access to the rest of the world lures and thereby might destroy the church and the family life. I have chosen this paragraph because it short and precisely describes a part of the Amish philosophy of life; why they do not interact or accommodate the rest of the world which I believe is important in order to understand the Amish as a whole. The statement herein is supported by other texts I have read, which validates this paragraph. ”Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish” by Tom Shachtman This book is written on the basis of four hundred hours of interviews conducted over a six-year period from 1999 till 2002, and in the period from 2002 till 2004 more interviews were conducted and some re-interviewed. The interviews resulted in the documentary “The Devil’s Playground”. The interviewees from the Old Order Amish are referred to by full names if they have been publicly identified in the press, otherwise, to preserve their privacy, they are referred to by first name and initials, and in certain cases some personal details have been altered. The book is basically an ethnographic piece of work where Tom Shachtman has got the opportunity to get very close to the Old Order Amish community in northern Indiana. It deals with aspects of young Amish experiencing “rumspringa”, which means “running around”. It is a period from the age of 16 till the age of around 21, before their baptism, where they are allowed to “run around”. The young Amish are granted the opportunity to explore the “English society” and for the first time in their lives, they on their own encounter the outside world. (Shachtman, 2006: 11). Since the young Amish are not yet 9 baptized, they are not subjects to the church’s rules about what is permitted and forbidden behaviors (Shachtman, 2006: 11). Shachtman describes very detailed how the young Amish experience their period of “rumspringa”, from how the boys pick up the girls to go courting; to how they party and what role the family plays in the mean time. The setting for the activities of the first party is near Shipshewana, north-central Indiana, Shachtman states that the activities in this area are similar to those in other major areas of Older Order Amish like Holms and Wayne counties in Ohio and Lancaster County in Pennsylvania. (Shachtman, 2006:4). Though, it is important to emphasize that many young Amish do not attend parties or in other ways participate in behaviors Amish parents and church officials consider wild. They might instead attend Sunday singings and take part in other organized activities supervised by church elders – tame stuff – but they have the opportunity to do things they have never done before. (Shachtman, 2006:4). The first party in the book takes place on the back acre of a farm south of Shipshe, as the locals call their town of Shipshewana, far away from the nearest town, a third of a mile from the farmhouse and hidden from the nearest road. Gathered are about 400 young Amish, most are from northern Indiana, but some have crossed the state line in Michigan and even from Missouri and Ohio. The preferred drink is beer, but also liquor as rum and vodka is present, some of the young do not know what drinking alcohol might do to them and will turn sick within short time. Others will smoke joints of marihuana or pipes of crystal methamphetamine, while some will be using cocaine. (Shachtman, 2006:8). Amish girls at the party: “Others shout in Pennsylvania Dutch and in English about how much it will cost to travel to and attend an Indianapolis rock concert, and the possibilities of having a navel pierced or hair cut buzz short.” (Shachtman, 2006:9). At noon most of the young Amish will be up and go shopping in a mall or watch a movie before the next party starts. (Shachtman, 2006:10). Around the age of 21, the period of “rumspringa” ends, this is where the young Amish are expected to make their final decision of whether they wish to commit themselves to the Amish life and the church, if they are baptized they are expected to leave the “English life” behind, get married and live Amish lives under the direction of the church. (Shachtman, 2006:14). Young Amish woman: “God talks to me in one ear, Satan in the other. Part of me wants to be Amish like my parents but the other part wants the jeans, the haircut, to do what I want to do.” (Shachtman, 2006:9). 10 The young Amish graduate from Amish schools at the age of 14 or 16, or leave public schools after the eighth grade, the Amish rarely attend public schools. After this, the girls often work in Shipshe, Middlebury, Goshen or other neighboring towns as waitresses, dishwashers, store clerk, seamstresses, bakers, and child-minders. In order to help assist with household expenses the girls will turn over most of their wages to their families. On top of the daily work routines, the girls also have their daily chores at home to fulfill; milk and feed the cows, provide fresh bedding for the horses, assist with housecleaning and laundry, preparing, serving and cleaning after the meals and caring for dozens of children. (Shachtman, 2006:5). The young Amish boys work in carpentry shops, in factories making recreational vehicles and mobile homes, in construction, or at the animal auction and flea market in town; none are farmers, though most still live at home. (Shachtman, 2006:5). According to Shachtman, the numbers of Amish are increasing very rapidly. 25 years ago there were 100,000 Amish; today there are an estimated 200,000 Amish, making up one percent of the population of the US. (Shachtman, 2006:25). Additionally, more than 80 percent of the young Amish do eventually decide to become baptized and become a part of the Amish community. In some areas, the “retention rate” exceeds 90 percent. (Shachtman, 2006:14). I have chosen this book because of the very thorough descriptions of what it is like to be a young Amish. Tom Shachtman has been granted the rare opportunity to observe and interview the young Amish at close hand. Furthermore the book is from 2006, which makes it of newer date. “The Old Order Amish: To Remain In The Faith or To Leave” by Thomas J. Meyers The paper is based on interviews with Amish informants in the Old Order Amish settlement of northeastern Indiana, which borders the State of Michigan. The statistical data provided is taken from the 1980 and 1988 editions of the Elkhart-LaGrange settlement directories. (Meyers, 1992:1). Counting 407 families. The paper presents statistical data of the possible increase and possible decrease of the Amish community, Meyers terms the Amish leaving the community as “defectors”, being “(…) children who has left their parental home and have been identified in the directory by their parents as having made the decision not to join the Amish church.” (Meyers, 1992:2). 11 Meyers clarifies that if looking exclusively at families with children who have left the Amish, 155 out of 407 families (38%), have only one child who decided to leave the Amish. The majority of the “defectors” seem to leave on their own, not influencing other brothers or sisters to leave the Amish. (Meyers, 1992:5). An average Amish family in the Elkhart-LaGrange settlement counts 7.39 children, where a large group of the “defectors” are the first, second or third child, compared to the fourth to the seventh child. (Meyers, 1992:7). According to Meyers, “Ericksen and Klein have suggested that producing children is perceived as one of the most important contributions that women make to Amish society.” (Meyers, 1992:7). Furthermore, Meyers states that those congregations bordering on small towns have a higher “defection” rate compared to those in more rural areas, due to the fact that it is more difficult to maintain the boundaries between the Amish and the non-Amish, leading to much more informal contact with the “English society”. (Meyers, 1992:10). Another important aspect is whether the Amish children attend public school or Amish school, because “Amish schools not only protect the children from non-Amish influence, they reinforce Amish values and help insure that peer groups will primarily include other Amish children.” (Meyers, 1992:17). In 1948 the first Amish school opened in the Elkhart-LaGrange settlement, already by 1988 this number had increased to 35. The majority of the schools built by 1988 were built after the consolidation into the Westview School Corporation in 1967. Over a period of 18 years, prior the consolidation, 8 Amish schools were built. In a two-year period after consolidation the number of Amish schools more than doubled. It has been important for me to find some empirical data, providing statistic of the “defectors” and reasons behind leaving the Amish to get a clear idea of the phenomenon. Meyers have often been quoted in other academic texts I have read and is also quoted in Tom Shachtman’s: Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish”, which validates his paper. 12 Theory In order to make an analysis of Amish culture and thereby answer my problem statement, this paragraph will make an introduction of the chosen theoreticians and their approaches to the subjects: culture, religion and identity. It also includes my account of theory of science. Clifford Geertz I have chosen to use Clifford Geertz’s theory of culture and religion in order to be able to analyze and understand why the Amish are not attracted by the “English lifestyle”. I will use his concepts of “thick description”, “webs of significance”, “ethos” and “worldview”. I believe his “thick description” will give me a better understanding of Tom Shachtman and his: “Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish”, since this book basically is an ethnographic piece of work. “Webs of significances” will create a basic understanding of the Amish culture and give me an insight in why they do as they do, both “ethos” and “world view” will provide the religious aspect in understanding the Amish as a community, but again also why they do as they do. As an anthropologist studying culture, Geertz is using ethnography in order to analyze, understand and define the cultural phenomena he observes - ethnography is also what he terms “thick description”. “If you want to understand what science is, you should look in the first instance not at its theories or its findings, and certainly not at what its apologists say about it; you should look at what the practitioners of it do.” (Geertz, 1973:5). Geertz draws his “cultural conclusions” by observing cultures through an interpretive approach, compared to other cultural theoreticians Geertz believes in “putting on more layers” in order to understand why people in a certain culture do as they do, whereas other cultural theoreticians believes “in pulling of layers” in order to get to the core of why people do as they do. According to Geertz, it is important that one first observes the culture and then tries to understand why people in the given culture do as they do. By observing rituals or symbols, one is able to describe and understand, why people do as they do - by doing this, one will also analyze the structures of meaning that occur. “Cultural analysis is (or should be) guessing at meanings, assessing the guesses, and drawing explanatory conclusions from better guesses, not discovering the Continent of 13 Meaning and mapping out its bodiless landscape.” (Geertz, 1973:20). The essential is to add to the “core”, that is: interpret. One of Geertz’s main theories is “Webs of Significance”. In order to understand Geertz’s approach to the concept of culture, I believe it is important to understand one of his most frequently used quotes: “Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning.” (Geertz, 1973:5). First of all, it is important to emphasize that the quote is a metaphor. Geertz consider man as a spider who enmeshes his own culture in a web where everything of importance will be saved and spun on, these webs end up being the meaning of life for the individual or the specific culture. Culture, “(…) it denotes an historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life.” (Geertz, 1973:89). By using symbols, man navigates through the webs and thereby finds out what is significant for “you” and for “me” in certain contexts, since these symbols help create reality - these webs constitute culture in society. The meaning of the symbols depends on how the culture interpret the symbols, though it is important to keep in mind, that depending on who regard the culture his/her view will affect the interpretation hereof. Geertz aims to make the concept of one culture comprehendible to foreigners of the concerned culture. Geertz defines religion as “(1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.” (Geertz, 1973:90). According to Geertz, symbols in a religious aspect amounts to “ethos” and “world view”. Symbols communicate to us about our world, and thereby also attempt to communicate a certain view or understanding hereof; symbols then form our knowledge, they roughly communicate our “world view” – a depiction of how the world is. At the same time the symbols represent our “ethos”, by letting us know how to answer or react to our experience; telling us how we live or how we should live, they represent our ideal, values and way of life. 14 Reflection of the Theory Geertz uses his “thick description” to thoroughly describe a given culture, which also might make him challenging to use; he does not propose a straightforward strategy of how to analyze cultural phenomena or cultural differences. At times it can be difficult to spot his concrete definition. Erik H. Erikson Furthermore, I have chosen to use Erik H. Erikson’s theory of identity in order to analyze if and how identity influences the young Amish’s decision to become or not become Amish, after their period of rumspringa. I have chosen to focus on identity to find out which conflicts/difficulties the young Amish are facing and why they end up choosing what they choose. Moreover, I find him relevant because his theory includes society’s influence and the social aspects of developing an identity. Erikson’s theory of identity “embraces society’s influence and the societal aspects of development (…)” (Identity Development: 42) and “the core concept of this theory is the acquisition of an ego-identity, and the exploration of identity issues becomes the outstanding characteristics of adolescence.” (Identity Development: 43). According to Erikson, human identity develop through a number of psychosocial crises where the individual has some developmental tasks consisting of some sort of psychological conflicts. (Hauge, 2005: 50). Erikson’s theory is shown in his “epigenetic diagram” consisting of eight stages depicting and identifying the developmental interaction between maturational advances and the social expectations made upon a child. (Identity Development: 43). Each stage has its own crisis/conflict and it is crucial how the crisis is resolved, since it will affect and further determine the outcome of the next stage, and thereby the entire personal and identity development. When in the period of adolescent, it is important that the young finds answers to questions like: “Who am I?”, “What do I represent?” and “What do I want to become?”. According to Erikson, “The search for an identity involves the establishment of a meaningful self-concept in which past, present and future are brought together to form a unified whole.” (Identity Development: 51). Erikson states that in societies where the social change happens rapidly, it is harder for the young to create an identity, since the elder generation is no longer able to act as role models. Additionally, he states that identity formation is a progress in close interaction with the socially important people such as parents, family, and e.g. a teacher in school, 15 he also believes that the young need a psychosocial moratorium where they have the possibility to try out and probe different roles. (Hauge, 2005: 166). “Since an identity can be found only in interaction with significant others, a process Erikson refers to as psychosocial reciprocity, the adolescent often goes through a period of a great need for peer group recognition and almost compulsive peer group involvement.” (Identity Development: 52). By this Erikson states that an adolescent can only find the answers of “Who am I?”, “What do I represent?” and “What do I want to become?” from the social feedback he/she will get from others stating their perception and evaluation of him/her. Reflection of the Theory To me it seems like Erikson’s theory of identity development is more or less a descriptive outline of the stages an individual go through and have to succeed in order to be gain a unified personality and identity, he does not provide any suggestion of how to succeed the stages successfully. Theory of Science Social constructivism is the philosophical and scientific theoretical basic assumption that all human knowledge is socially constructed. This means that all kinds of realization is acquired through a perspective or a realm of understanding/context which is not inherited, but rather is a result from the culture and the culture’s historical past one takes part in. This means that one’s “world view” and “reality” are created on the basis of the society and the culture one is born and bred in. Social constructivism claims that a given phenomenon in question, “in fact is man-made and is imprinted by its human origin: it is formed and marked by human interests.” (Collin, 2012: 248). Throughout the assignment I have chosen to analyze my empirical data from a socioconstructive perspective. I have chosen this point of view because one could say that Amish has created their own reality, and thereby they have also created their societal identity and personal identity – I believe, they will always aim to represent themselves in accordance to their norms, values and what they considered socially accepted. If a certain religion or “way of life” succeeds in achieving “believers” of the religion or “way of living”, a new value is added to it and thereby, through recognition, a new “reality” is created around the religion or “way of living”; and this new “reality” is real to 16 those who believe in the value of it. A religion or “way of life” becomes a “reality” from the point where people start to realize and add value to it – it is only when people start to attribute a certain religion or “way of life” significance that it is substantiated. In general, considering a “world view” from a socio-constructive perspective is the essence in dealing with the Amish, religion and culture, otherwise the terms/concepts would not exist as a “discipline” and to some “different”. Fundamentally, culture is based on different “world views” which sometimes can be difficult to decode when encountering one another. Regarding Amish I see two conflicting “world views” - The Amish: “We are allowed to meet and deal with the English society” and “We should under no circumstances interact with the English society”. When looking at the assignment as a whole, it is important to realize that the Amish are to be seen and considered stagnating – meaning that they are slow changing, but yet still expanding. If the majority of the Amish accepted contact with the “English society”, their “way of life” and communities would be, very, different and in the worst-case scenario, not existing. Analysis In this paragraph, I will attempt to shed light on why the young Amish not seem to be attracted by the “English lifestyle” during their period of “rumspringa” and how the Amish communities, in these days, manage to grow faster than ever. To understand the Amish culture I will be using Clifford Geertz’s theory of culture and to understand the identity processes happening during the time the young Amish have to decide whether they want to commit themselves to the Amish community and church or whether they decide to leave, I will be using Erik H. Erikson’s identity theory. The Amish’s present fundamental values and norms have roots in the “Gelassenheit” and in the “Ordnung”, the Amish children are born into the Amish belief and into the Amish way of life, they have not experienced any other way of life and the contact to the outside world is in many communities spare or completely non-existing. The “Gelassenheit” and the “Ordnung” are the foundation of what Clifford Geertz calls “webs of significance”, “world view” and “ethos” and combined, according to Erik H. Erikson, they further affect and result in a personal identity. They are the guidelines in the Amish community showing how to live a righteous life, how to view the world and lastly, 17 defining who the Amish are and what they represent. The Amish children grow up with a very strict “webs of significance” which forms and creates their identity (Geertz’s ethos) and their perception of reality (Geertz’s world view) – a perception of how things should be; from the day they are born they learn how to behave according to the “Ordnung” and the Bible. According to Meyers, an average Amish family will have 7.39 children, which I believe is many compared to the approximate number I would guess an American family will have today, and the Amish children will from the beginning play a significant role in the family, as they have their “roles/jobs” to fulfill. I believe the Amish depend more on their children’s help because of their way of life, their “webs of significance”, “ethos” and “world view” combined - their concept of how things should be and the fact that they believe they shall separate themselves from the rest of the world, amount to the needing of having children to help with the daily chores and house hold expenses. Moreover Meyers states that “Ericksen and Klein have suggested that producing children is perceived as one of the most important contributions that woman make to Amish society.” (Meyers, 1992:7) The children grow up with a clear idea and moral of how life and family life should be (ethos), which I believe most certainly affects their identity and who they become. Another important aspect about the Amish culture is the Amish schools, in school they are taught by Amish teachers and who, I believe, also will teach them about the Amish values and norms (webs of significances), and therefore also will be transmitted to them there. “Amish schools not only protect the children from non-Amish influence, they reinforce Amish values and help insure that peer groups will primarily include other Amish children.” (Meyers, 1992:17). I believe, this reinforces the “world view” and the “ethos” they have learned from home, and in the end, this will also have a crucial influence on their identity and who they become, because as Erikson stated, adolescents’ “identity formation is a progress in close interaction with the socially important people”. Furthermore, the peer groups they will use to compare themselves with and get the important socially and identity developing feedback later in life are under the same influence as themselves. The strict “webs of significance” is seen in the fact that the young Amish only attend school until the eighth grade, to some extent it is important to go to school and e.g. learn to speak English, but what matters most is the family and their survival; the ethos of life. When the young Amish have left school they are expected to work, girls e.g. as waitresses, dishwashers or store clerks and boys e.g. in carpentry 18 shops, in construction etc. (Shachtman, 2006:5) – through the jobs they are able to possess, it is very clear to see the gender roles (identity), and hand in their wages to support the family financially. Their “web of significance”, their “world view” and their “ethos” are brought up with the vision of how to get by through having a close family where everybody support and help each other; of course this will also become a influential affect to their future identity. I believe they become used to living a simple life with as few aids as possible and no one else to depend on than themselves and their family, in precise accordance to the “Gelassenheit”. According to Meyers, the Amish living close to “English” cities witness more “defectors” than the more rural areas, simply because it is harder to maintain their “webs of significances” and the boundaries becomes more indistinct. Even though the contact might be informal it is enough to affect their “ethos” and affect, maybe even change, their “world view”. I believe this might be due to the fact that the young Amish get triggered by an easier way of life and see the positive possibilities in a change. Moreover he states, that it is often one of the first three children who decides to leave the community and the rest of the children remain unaffected of this “defect”. 38% of the Amish families, within the Elkhart-LaGrange settlement, experience having a child who decides to leave the community, according to Meyers statistics that would be 155 families out of 407, and thereby approximately 155 young Amish who “defects”. I believe this numbers are very consistent with Shachtman’s statement indicating that the numbers of Amish are increasing very rapidly. 25 years ago there were 100,000 Amish; today there are an estimated 200,000 Amish, making up one percent of the population of the US. (Shachtman, 2006:25). When the Amish adolescents turn 16 they get into the period of “rumspringa”, it is also at this point they according to Erikson are considered to be in the period of adolescent and have to find answers to the vital questions: “who am I?”, “what do I represent?” and “what do I want to become?”. They now have the opportunity to experience the “English society”, for many this will be the first encounter without having knowledge of what to expect or what they venture into. The young Amish only know very little or nothing about the “web of significances” of the “English society” and therefore it is impossible for them to know how to “navigate” in the “English webs of significance”. During this period, they will gain freedom which they are not used to; they will feel that they for the first time are not supervised by their parents or the church - for the first time, they step outside their secure and well-known “webs of significances”, their “ethos” and “world 19 view” is turned upside down. In the light of Erikson’s theory, I believe the experiences they gather must account for and make up the foundation of the answers to their crucial questions of “who they are” and “what they want to become”, in order to form a future unified identity, “The search for an identity involves the establishment of a meaningful self-concept in which past, present and future are brought together to form a unified whole.” (Identity Development: 50). According to Shachtman, the young Amish will attend a lot of parties during their “rumspringa”, they will dress like the “English” adolescents, drink alcohol, smoke pot and some will even experiment with hard drugs. “Since the young Amish are not yet baptized, they are not subjects to the church’s rules about what is permitted and forbidden behaviors (Shachtman, 2006: 11) – there are no restrictions or rules for what they can do and cannot do.” To me it seems like there is no limit for what they want to put themselves through, it seems like their entire Amish “webs of significances”, “ethos” and “world view” is completely overruled by all the opportunities they now possess. Amish girls at the party: “Others shout in Pennsylvania Dutch and in English about how much it will cost to travel to and attend an Indianapolis rock concert, and the possibilities of having a navel pierced or hair cut buzz short.” (Shachtman, 2006:9). They test some boundaries that they know they cannot test within the Amish “webs of significances”, and in one way or another, this might affect or change their entire “ethos” and “world view” and might question the identity they have developed up until now within the Amish community. A young Amish woman states: “God talks to me in one ear, Satan in the other. Part of me wants to be Amish like my parents but the other part wants the jeans, the haircut, to do what I want to do.” (Shachtman, 2006:9). According to Shachtman, it is not all young Amish who attend parties or in other ways participate in behaviors Amish parents and church officials consider opposing to their “webs of significances”, “ethos” and “world view”. Instead they attend Sunday singings and will take part in organized activities supervised by church elders, but they have the opportunity to do things they have never done before. (Shachtman, 2006:4). I do not believe that their identity development will “suffer” from not having the same experiences as those who choose to live out a wild adolescent, but it is clear that their future identity not will have the same frame of references. The Amish “ethos” and “world view” will be further nailed and attached to their decision of whether to become Amish or not. With all that said, I find it very notably that 80 or 90 percent of the young Amish, after their “rumspringa”, chose to commit themselves to the community and to the church. What I thought would be 20 tempting in the “English webs of significances”, freedom and an easy way of life, is not strong enough to affect them in such degree that they choose to “defect”. I believe this is due to the strict “webs of significances”, “ethos” and “world view” they have been raised under; their entire childhood has had the family and the church as the main incentives and has become such big part of their identity that the consequences of leaving Amish might seem immensely huge. I think the identity they have acquired during their childhood is crucial for the decision they make. According to Jørgensen, the Amish speak Pennsylvanian Dutch at home, which I also understand as in the community, and learn to speak English in school. Erikson do not mention language as a part of one’s identity, but I believe language plays a significant role when it comes to distinguishing identities from one another and of course also in community’s “webs of significances”, there is almost no bigger symbol of alienation than language. 21 Discussion In this paragraph, my aim is to discuss the results from the analysis. After having studied the Amish, their way of life and their “webs of significances” the active role of the “Gelassenheit” and “Ordnung” in everything they do is very obvious. The Amish core values have been transferred from generation to generation and their way of life and active choices gives them the ability to sustain these values. It is seen that in those areas where the boarder between Amish and “English” is small, they experience a greater “defector rate”. In that context, it makes good sense that the Amish believe they are to separate themselves from the rest of the world and not accommodate, simply in order to “survive”. Even though the young has been raised Amish and probably have attended an Amish school, where all Amish values also have been transmitted, it has not been enough for him/her to stay within the community. Meyers state that 38% of the Amish families experience having one child who decide to leave the community, at first glance that seems like a high percentage, but in the light of an average Amish family will have 7.39 children, the number is not that high. At first I believed the period of “rumspringa” would create many “defectors”, but it quickly became very clear to me that it was not the case, because the majority of the adolescents later decide to become baptized and by doing so, to commit themselves to the church, the community and the Amish way of life. As stated earlier, I believe the identity they have acquired during their childhood is crucial for their final decision, maybe the freedom seems too stressful and the choices they will have to choose between too many. They are used to have strict guidelines for how to live righteous, in accordance to God. I believe it possible to discuss whether the young Amish actually meet the “English society” during their parties, since the party Shachtman describe is situated on a field with, what I believe, is mostly young Amish. If they do not have realistic and actual idea of what the “English society” represents, this will affect their choice of becoming Amish or not. Though it is important to keep in mind, that not all young Amish choose a wild “rumspringa” and in that case I find it more obvious that they choose the baptism. I believe “rumspringa” is an important process in order to make sure that the adolescents make the decision of becoming Amish on their own, that they are aware of the commitment and the responsibility following when choosing Amish – they make an active choice and know what they choose and what they opt out of. 22 The fact that Pennsylvanian Dutch is their mother tongue creates a bigger gap between the Amish community and the “English society”, I believe it makes it easier for them keep the two separated and in the sense alienate everything that is “English”. Conclusion When looking at my bachelor thesis as a whole I believe it becomes very clear that it is the same factors all combined that make up the reason for the young Amish to stay within the Amish community and the reason why Amish is still increasing. The young Amish encounter the “English society” and its challenges without having any preparation of what they are going to meet; their childhood has to a certain extend been very protective and very much structured. When they reach adolescent and the period of “rumspringa”, they carry everything that so far have formed their identity, their way of thinking and their way of viewing the world. This “baggage” has been imprinting them in their homes, in school, in church and in the community; and all of a sudden they are free. This freedom might be overwhelming to them, and the contradictions between their community and the “English society” too extensive for them to choose to leave the Amish behind. The Amish culture, with roots in the “Gelassenheit” and the “Ordnung”, is a counterculture to the “English society, I believe, they value collectivism and humility whereas the “English society” seem to value individualism and personal development. The fact that many young Amish decide to become baptized is one of the reasons why the Amish can continue their increase. Another fact is that a family on average will have 7.39 children, balancing out the few who decide to leave, even in the areas bordering “English cities” where the contact with the outside world is much frequent. Moreover the brother or sister who leaves does not seem to affect the rest of the children to leave also. And last but not least, in the light of Shachtman’s example of an Amish party, one can argue if it really is the “English society’s” norms and values they meet. They party on what I believe is a field, get wasted, wake up during the next day and go shopping, when the weekend is over they return to the farms and their family to fulfill their chores for the rest of the week until everything repeats itself the next weekend. 23 Bibliography Borries, Erik. 1998. “ Amishfolket”. Toptryk Grafisk, Gråsten. Bridger, Jeffrey C. , A.E. Luloff , Louis A. Ploch and Jennifer Steele. 2001. “A Fifty-Year Overview of Persistence and Change in an Old Order Amish Community”. Journal of the Community Development Society. Academic Search Premier. Collin, Finn and Simo Køppe, editor. 2012. “Humanistisk Videnskabsteori”. Finn Collin. DR Multimedie. 248-275. Crowley, William K. “Old Order Amish Settlement: Diffusion and Growth”. Academic Search Premier. Egenes, Linda. 2009. “Visit with the Amish, Impressions of the Plain Life”. University of Iowa Press. Erikson, Erik H. 1968. “Identitet, Ungdom og Ungdomskriser”. Hans Ritzels Forlag A/S. Erikson, Erik H. 1968. “Barnet og Samfundet”. Hans Ritzels Forlag A/S. Erikson, Erik H. and Paul Roazen. 1976. “The power and limits of a vision”. The Free Press, A Division of Macmillian Publishing Co., Inc. 86-107. “Erik Erikson’s Theory of Identity Development”, last modified May 24, 2014 http://childdevpsychology.yolasite.com/resources/theory%20of%20identity%20eriks on.pdf Geertz, Clifford. 1973. ”The Interpretation of Cultures”. Basic Books, A Division of HarperCollins Publishers. 3-30. 88-125. Greksa, L., P. “Population Growth and Fertility Patterns in An Old Order Amish Settlement”. 2000. Case Western Reserve University. Academic Search Premier. Hauge, Lene and Mogens Brørup, editor. 2005. “Gyldendals Psykologi Håndbog”. Bo Møhl and May Shack. Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag A/S, København. 50-53. Hosterlet, John A., editior. 1989. “Amish Roots, A Treasury of History, Wisdom and Lore”. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Jørgensen, Nanna Dissing Bay. “Amish”. Journalist, iBureauet/Dagbladet Information, 2005. Faktalink. (http://www.faktalink.dk.zorac.aub.aau.dk/titelliste/amis) 24 Meyers, Thomas J.. 1992. “The Old Order Amish: To Remain In The Faith or To Leave”. Paper presented at the American Sociological Association meetings on August 20, 1992, in Pittsburgh, Pa. 1-20. Miller, F. Wayne. 2007. “Negotiating with Modernity: Amish Dispute Resolution”. Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution. Academic Search Premier. Nolt, M. Steven. 1992. ”A History of the Amish”. Good Books, Intercourse, Pennsylvania 17534. 3-42 Shachtman, Tom. 2006. “Rumspringa, To Be or Not To Be Amish”. Tom Shachtman and Stick Figure Production. 3-35. Schweider, Elmer and Dorothy Schweider. 2009. “A Peculiar People, Iowa’s Old Order Amish”. First University of Iowa Press Edition. 23-37. 55-80. Egenes, Linda. 2009. “Visit with the Amish, Impressions of the Plain Life”. University of Iowa Press. Guranio, Mark. “For Amish, Fastest-Growing Faith Group in US, Life is Changing”. The Christian Science Monitor, November 12, 2012. Accessed May 20, 2014. http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2012/1130/For-Amish-fastest-growingfaith-group-in-US-life-is-changing Greksa, L., P. “Population Growth and Fertility Patterns in An Old Order Amish Settlement”. 2000. Case Western Reserve University. Academic Search Premier. 25