Lecture 32 Review

advertisement

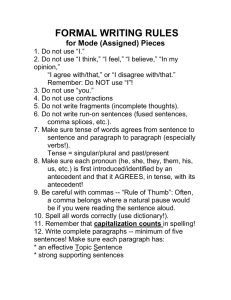

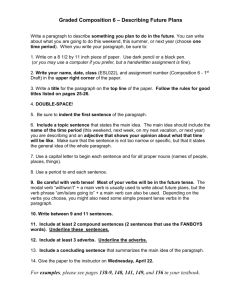

English Comprehension and Composition – Lecture 32 Objectives: • Review of the Course Contents Grammar Writing (Composition) Message Composition Presentation Skills Strengthening Your Reading Comprehension • Analyze the time and place in which you are reading ; mental fatigue or distractions or interruptions • Rephrase each paragraph in your own words; approach complicated material sentence by sentence, expressing each in your own words. • Read aloud sentences or sections that are particularly difficult; makes complicated material easier to understand. • Reread difficult or complicated sections • Slow down your reading rate - reading more slowly and carefully will provide you with the needed boost in comprehension. • Turn headings into questions - Refer to these questions frequently and jot down or underline answers. • Write a brief outline of major points - This will help you see the overall organization and progression of ideas. [for more complicated passages] • Highlight key ideas - After you've read a section, go back and think about and highlight what is important. • Write notes in the margins - Explain or rephrase difficult or complicated ideas or sections. • Determine whether you lack background knowledge - Comprehension is difficult, at times, and it is impossible, if you lack essential information that the writer assumes you have. Source: http://academic.cuesta.edu/acasupp/as/304.HTM READING SKILLS Skimming • Skimming is used to quickly gather the most important information, or 'gist'. Run your eyes over the text, noting important information. Use skimming to quickly get up to speed on a current business situation. It's not essential to understand each word when skimming. Examples of Skimming: • The Newspaper (quickly to get the general news of the day) • Magazines (quickly to discover which articles you would like to read in more detail) • Business and Travel Brochures (quickly to get informed) Scanning • Scanning is used to find a particular piece of information. Run your eyes over the text looking for the specific piece of information you need. Use scanning on schedules, meeting plans, etc. in order to find the specific details you require. If you see words or phrases that you don't understand, don't worry when scanning. Examples of Scanning • The "What's on TV" section of your newspaper. • A train / airplane schedule • A conference guide Vocabulary in Context Context clues are words and phrases in a sentence which help you reason out the meaning of an unfamiliar word. Oftentimes you can figure out the meanings of new or unfamiliar vocabulary by paying attention to the surrounding language. Below are the types of clues, signals and examples of each clue. Type of Context Clue Antonym or Contrast Clue Definition Phrases or words that indicate opposite Signals but, in contrast, however, instead of, unlike, yet Examples Unlike his quiet and low key family, Brad is garrulous. Type of Context Clue Definition or Example Clue Definition Phrases or words that define or explain Signals is defined as, means, the term, [a term in boldface or italics] set off with commas Examples Sedentary individuals, people who are not very active, often have diminished health. Type of Context Clue General Knowledge Definition The meaning is derived from the experience and background knowledge of the reader; "common sense" and logic. Signals the information may be something basically familiar to you Examples Lourdes is always sucking up to the boss, even in front of others. That sycophant just doesn't care what others think of her behavior. Type of Context Clue Restatement or Synonym Clue Definition Another word or phrase with the same or a similar meaning is used. Signals in other word, that is, also known as, sometimes called, or Examples The dromedary, commonly called a camel, stores fat in its hump. PREVIEWING Previewing a text means gathering as much information about the text as you can before you actually read it. You can ask yourself the following questions: What is my purpose for reading? Are you asked to summarize a particular piece of writing? Are you looking for the thesis statement or main idea? Or are you being asked to respond to a piece? If so, you may want to be conscious of what you already know about the topic and how you arrived at that opinion. What can the title tell me about the text? Before you read, look at the title of the text. What clues does it give you about the piece of writing? Good writers usually try to make their titles work to help readers grasp meaning of the text from the reader's first glance at it. Who is the author? If you have heard the author's name before, what comes to your mind in terms of their reputation and/or stance on the issue you are reading about? Has the author written other things of which you are aware? How does the piece in front of you fit into to the author's body of work? How is the text structured? Sometimes the structure of a piece can give you important clues to its meaning. Be sure to read all section headings carefully. Also, reading the opening sentences of paragraphs should give you a good idea of the main ideas contained in the piece. SOURCE: http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/reading/critread/pop5a.cfm READING FOR MAIN IDEA The main idea of a passage or reading is the central thought or message. In contrast to the term topic, which refers to the subject under discussion, the term main idea refers to the point or thought being expressed. Reading Tips 1. As soon as you can define the topic, ask yourself “What general point does the author want to make about this topic?” Once you can answer that question, you have more than likely found the main idea. 2. Most main ideas are stated or suggested early on in a reading; pay special attention to the first third of any passage, article, or chapter. That’s where you are likely to get the best statement or clearest expression of the main idea. 3. Pay attention to any idea that is repeated in different ways. If an author returns to the same thought in several different sentences or paragraphs, that idea is the main or central thought under discussion. Which one of these is a complete sentence??? 1. Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall. 2. Outside the window 3. Political parties SENTENCE A group of words that makes complete sense is called a sentence. Examples: "Children are all foreigners." (Ralph Waldo Emerson) "I have often wanted to drown my troubles, but I can't get my wife to go swimming." (attributed to Jimmy Carter, among others) "Be who you are and say what you feel, because those who mind don't matter and those who matter don't mind." (Theodor Geisel) Open the door! PARTS OF A SENTENCE • Every sentence has two parts • The part that names the person or thing we are talking about is called a subject • The part that tells something about the subject is called the predicate of the sentence. Example: They wake up early in the morning. Sentence Types According to Meaning English has four main sentence types: • Declarative Sentences are used to form statements. Examples: "Mary is here.", "My name is Mary." • Interrogative Sentences are used to ask questions. Examples: "Where is Mary?", "What is your name?" • Imperative Sentences are used for commands. Examples: "Come here.", "Tell me your name.“” • Conditional Sentences are used to indicate dependencies between events or conditions. Example: "If you cut all the trees, there will be no forest." SENTENCE STRUCTURES Sentence Types One way to categorize sentences is by the clauses they contain. (A clause is a part of a sentence containing a subject and a predicate.) There are 4 types of sentences in this category: Simple • Contains a single, independent clause. – I don't like dogs. – Our school basketball team lost their last game of the season 75-68. – The old hotel opposite the bus station in the center of the town is probably going to be knocked down at the end of next year. Compound • Contains two independent clauses that are joined by a coordinating conjunction. The most common coordinating conjunctions are: and, or, but, so. – I don't like dogs, and my sister doesn't like cats. – You can write on paper, or you can use a computer. – A tree fell onto the school roof in a storm, but none of the students was injured. Complex • Contains an independent clause plus one dependent clause. (A dependent clause starts with a subordinating conjunction. Examples: that, because, although, where, which, since.) – I don't like dogs that bark at me when I go past. – You can write on paper, although a computer is better. – None of the students were injured when the tree fell through the school roof. Compound-complex • Contains 3 or more clauses (of which at least two are independent and one is dependent). – I don't like dogs, and my sister doesn't like cats because they make her sneeze. – You can write on paper, but using a computer is better as you can easily correct your mistakes. – A tree fell onto the school roof in a storm, but none of the students was injured although many of them were in classrooms at the top of the building. MODIFIERS • A word, phrase, or clause that functions as an adjective or adverb to limit or qualify the meaning of another word or word group (called the head). • Modifiers that appear before the head are called premodifiers. Modifiers that appear after the head are called postmodifiers. Dangling Modifiers • A dangling modifier is a phrase or clause that is not clearly and logically related to the word or words it modifies (i.e. is placed next to). Two notes about dangling modifiers: • Unlike a misplaced modifier, a dangling modifier cannot be corrected by simply moving it to a different place in a sentence. • In most cases, the dangling modifier appears at the beginning of the sentence, although it can also come at the end. Misplaced Modifiers • A misplaced modifier is a word, phrase, or clause that is improperly separated from the word it modifies / describes. • Because of the separation, sentences with this error often sound awkward, ridiculous, or confusing. Furthermore, they can be downright illogical. PUNCTUATION MARKS Punctuation marks on a page are similar to signs on a road. They guide you and direct you. 1. A period ( . ) ends a declarative or imperative sentence. I live in Pasadena. They don’t live in Pasadena. Listen to me. Don’t drink and drive. Please come here. Eat your vegetables. 2. A question mark ( ? ) ends an interrogative sentence. Do you live in Pasadena? Don’t you like chocolate ice cream? 3. An exclamation mark ( ! ) ends an exclamatory sentence (a sentence that contains a lot of emotion). Help! Stop! Don’t call me again! 4. A comma ( , ) separates items in a list. I like coffee, soda, milk, and tea. Sara, Maria, Robert and Steven will eat lunch. 5. A semicolon separates equal parts of a sentence. Mary is at home; Bob is at school. Give me a hamburger, with onions and lettuce; a coke, with a straw; and fries, with ketchup. 6. A colon ( : ) usually precedes a list. Bring these things with you: a book, a pencil, and a dictionary. 7. A dash ( – ) usually indicates a break in thought. I’ll have a hot dog with mustard – no, make that ketchup. 8. A hyphen ( - ) separates syllables to make a word easier to read. co-ordinate re-elect pray-er A hyphen also separates syllables when it’s necessary to continue a word on the following line. 9. Parentheses ( ) or a pair of dashes contain extra information. John (my brother) is coming to the party. John – my brother – is coming to the party. 10. An ellipsis (...) shows that information is missing or deleted. “To be or not...the question.” (“To be or not to be. That is the question.”) 11. Quotation marks (“ ”) enclose the exact words of a person. Maria said, “Where are the keys?” 12. An apostrophe ( ’ ) is a substitute for a letter or letters (in a contraction). isn’t = is not can’t = cannot don’t = do not I’ll = I will I’m = I am He’s sick. = He is sick. Bob’s rich. = Bob is rich. What’s new? = What is new? They’ve worked. = They have worked. ’99 = 1999 An apostrophe also shows possession. This is Sara’s book. (Don’t say: This is the book of Sara.) Where is the dog’s dish? 13. Capitalization: Begin all sentences with a capital letter (i.e., capitalize the first word in all sentences) and end all sentences with a punctuation mark. Capitalize the first word in a sentence and finish the sentence with a punctuation mark. Verb Tense • A verb indicates the time of an action, event or condition by changing its form. Through the use of a sequence of tenses in a sentence or in a paragraph, it is possible to indicate the complex temporal relationship of actions, events, and conditions The four past tenses are 1. the simple past ("I went") 2. the past progressive ("I was going") 3. the past perfect ("I had gone") 4. the past perfect progressive ("I had been going") The four present tenses are 1. the simple present ("I go") 2. the present progressive ("I am going") 3. the present perfect ("I have gone") 4. the present perfect progressive ("I have been going") The four future tenses are 1. the simple future ("I will go") 2. the future progressive ("I will be going") 3. the future perfect ("I will have gone") 4. the future perfect progressive (“I will have been going”) The Function of Verb Tenses The Simple Present Tense The simple present is used to describe an action, an event, or condition that is occurring in the present, at the moment of speaking or writing. The simple present is used when the precise beginning or ending of a present action, event, or condition is unknown or is unimportant to the meaning of the sentence. The simple present is used to express general truths such as scientific fact. The simple present is used to indicate a habitual action, event, or condition The simple present is also used when writing about works of art The simple present can also be used to refer to a future event when used in conjunction with an adverb or adverbial phrase The Present Progressive • While the simple present and the present progressive are sometimes used interchangeably, the present progressive emphasizes the continuing nature of an act, event, or condition. • The present progressive is occasionally used to refer to a future event when used in conjunction with an adverb or adverbial phrase, • The present perfect tense is used to describe action that began in the past and continues into the present or has just been completed at the moment of utterance. The present perfect is often used to suggest that a past action still has an effect upon something happening in the present. The Present Perfect Progressive Tense Like the present perfect, the present perfect progressive is used to describe an action, event, or condition that has begun in the past and continues into the present. The present perfect progressive, however, is used to stress the on-going nature of that action, condition, or event. The Simple Past Tense The simple past is used to describe an action, an event, or condition that occurred in the past, sometime before the moment of speaking or writing. The Past Progressive Tense The past progressive tense is used to described actions ongoing in the past. These actions often take place within a specific time frame. While actions referred to in the present progressive have some connection to the present, actions referred in the past progressive have no immediate or obvious connection to the present. The on-going actions took place and were completed at some point well before the time of speaking or writing. The Past Perfect Tense The past perfect tense is used to refer to actions that took place and were completed in the past. The past perfect is often used to emphasize that one action, event or condition ended before another past action, event, or condition began. The Past Perfect Progressive Tense The past perfect progressive is used to indicate that a continuing action in the past began before another past action began or interrupted the first action. The Simple Future Tense The simple future is used to refer to actions that will take place after the act of speaking or writing. The Future Progressive Tense The future progressive tense is used to describe actions ongoing in the future. The future progressive is used to refer to continuing action that will occur in the future. The Future Perfect Tense The future perfect is used to refer to an action that will be completed sometime in the future before another action takes place. The Future Perfect Progressive Tense The future perfect progressive tense is used to indicate a continuing action that will be completed at some specified time in the future. This tense is rarely used. Word Order in English Word Order in Affirmative Sentences subject verb(s) object I speak English I can speak English Word Order in Affirmative Sentences subject verb I will tell indirect object you direct place object the story time at tomorrow. school Word Order in Past Perfect Simple Negative Sentences indirect direct subject verbs place object object I had you not told the story time at tomorrow school Word Order in Subordinate Clauses Conjunction because indirect direct subject verb(s) place object object I will tell I don't have you the story time time at tomorrow school ... now. Position of Time Expressions and Adverbs of Frequency subject auxiliary/be I adverb main verb object, place or time often go swimming in the evenings. play tennis. He doesn't always We are usually here in summer. Word Order in Questions Interro auxiliary other indirect direct subject verb(s) object object -gative verb What When would you like to tell Did you have were you place time me a party in your yesterday? flat here? DETERMINERS FUNCTION AND CLASSES Function Determiners are words placed in front of a noun to make it clear as to what the noun refers to. The word 'people' by itself is a general reference to some group of human beings. If someone says 'these people', we know which group they are talking about, and if they say 'a lot of people' we know how big the group is. Classes of Determiners • Definite and Indefinite articles the, a, an • Demonstratives this, that, these, those • Possessives my, your, his, her, its, our, their • Quantifiers a few, a little, much, many, a lot of, most, some, any, enough, etc. • Numbers one, ten, thirty, etc. • Distributives all, both, half, either, neither, each, every • Difference words other, another • Question words Which, what, whose • Defining words which, whose PREPOSITIONS A preposition is a word that relates a noun or pronoun to another word in a sentence. "The dog sat under the tree." Parallelism • We wanted to cook and to go swimming. We wanted to cook and to swim. • He is talented, intelligent and has charm. He is talented, intelligent and charming. • Mary likes hiking, swimming, and to ride a bicycle. Mary likes hiking, swimming, and riding a bicycle. Parallel structure means that two or more ideas in a sentence are expressed in similar form. And, but and or usually join similar terms—two or more nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, phases or clauses. • My ambition is to be a doctor and to specialize in surgery. (Parallel) Sentence Fragments Every sentence has to have a subject and a verb in order to be complete. If it doesn't, it's a fragment. That's easy enough if you have something like –Ran into town. (no subject) –The growling dog. (no verb) • A fragment may be missing a SUBJECT Threw the baseball. (Who threw the baseball?) • A fragment may be missing a VERB Mark and his friends. (What about them?) • A fragment may be missing BOTH Around the corner. (Who was? What happened?) You can correct a fragment by adding the missing part of speech. Add a subject: Rob threw the baseball. Add a verb: Mark and his friends laughed. Add both: A dog ran around the corner. Run-on Sentences Two sentences that the writer has not separated with an end punctuation mark, or has not joined with a conjunction. Here are three examples of run-ons: 1. Tyler delivered newspapers in the rain he got very wet. 2. Kevin and his dog went for a walk it was a beautiful day. 3. On Monday we went outside for recess it was fun. There are three ways to correct a run-on: 1.Add a period and a capital letter. 2.Add a semicolon. 3.Add a comma and a conjunction. Pre-writing Techniques 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Free-writing Note keeping Brain storming Mind mapping Journalistic questions (how +5 w’s) What is Pre-writing? Pre-writing is the first stage of the writing process, aimed to “discover and explore our initial ideas about a subject.” At the beginning of writing, it is usual to find yourself totally blank, without ideas about what to say. Pre-writing techniques, make it much easier to start a writing. 1. Free-writing • “Free Writing” is like pouring all of your thoughts onto paper. • Don’t take your pen off the page; keep writing for the entire time. • If you don’t know what to write, write “I don’t know what to write” until you do. • Don’t try to sort “good” and “bad” ideas. • Don’t worry about spelling and grammar. 2. Note keeping/ Keeping a Journal Keeping a journal is an excellent way to practice your writing skills. Your journal is mostly for you. It’s a private place that you record your experiences and your inner life; it is the place where, as one writer says, “I discover what I really think by writing it down.” How to keep a journal? • You can keep a journal in a notebook. • Every morning or night, or several times a week, write for at least fifteen minutes in this journal. • Don’t just record the day’s events. Instead write in detail about what most angered, moved or amused you that day. • Your journal is private, so don’t worry about grammar or correctness. 3. Brain Storming Brainstorming is a strategy of listing all the terms related to the topic. No need to worry about whether those ideas are useful or not. You just jot down all the possibilities. The more, the better. Then look back things you have listed and circle those that make a sense to the topic. Often, brainstorming looks more like a list while free writing may look more like a paragraph. With either strategy, your goal is to get as many ideas down on paper as you can. 4. Mind Mapping • Mind mapping, Clustering, Mapping, Idea mapping or Webbing is a "visual of outlining”. It is another way to organize your ideas. • Start with your topic in the center, and branch out from there with related ideas. • Use words and phrases, not complete sentences. 5. Journalistic Questions (How + 5 w’s) Journalistic techniques refer to asking yourself six questions, How? What? Where? When? Which? Who? With these questions, you can fully explore ideas about the topic you are about to write and put everything down in detail. In this process, you should not spare hard efforts on every question but make it as flexible as possible. In other words, some Ws (such as what or who) should be attached with importance, while others (such as where or who) can be ignored. This largely depends on your topic. What is a paragraph? A developed, but manageable thought. Writing a Paragraph Hamburger Model The hamburger paragraph format provides a clear structure for writing an organized paragraph. Essentials of a Good Paragraph • Unity • A good topic sentence • Logical sequence of thoughts • Variety • A comprehensive final sentence ESSAY WRITING Kinds and Characteristics An essay is a short piece of writing that discusses, describes or analyzes one topic. KINDS OF ESSAYS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Descriptive Definition Compare and contrast Cause and effect Narrative Process Argumentative Critical Imaginative Characteristics of an Essay • • • • • Unity Order Brevity Style The Personal Touch Writing a Précis A précis is a short summary. “It is a brief, original summary of the important ideas given in a long selection. Its aim is to give the general effect created by the original selection." RULES OF PRÉCIS WRITING 1) Read the given passage carefully at least three times in order to be able to grasp what the writer has said. 2) Underline the important points to be included in your précis. A point is important if it is intimately connected with the main subject. 3) Use your own language in the précis. While words and phrases from the original may be used in the précis. Whole sentences should never be lifted out of the original to be included in it. 4) The précis should be roughly one-third of the original passage. Always prepare a rough draft first and count the words. If you find that it is too long, shorten it by removing what seems unessential and by condensing, phraseology. If it turns out to be too short, read the original to see what more can be added to the précis. 5) Examples, illustrations, and comparisons should be left out of the précis. Figures of speech should be removed and the ideas are expressed in clear, direct language. 6) Your own comments on the ideas of the précis are absolutely forbidden. 7) See that your précis is a readable piece of English and that its ideas can be understood even by a person who has not gone through original. This is very important. 8) Your précis should be connected whole. As such it should not be divided into paragraphs. 9) Don't use the direct form of speech in précis. 10) Think of a suitable title for the précis if it is required. The title should not be a complete sentence. 11) Indicate the number of words in your précis at the end. MEMO WRITING “A memo is a short, to the point communication conveying your thoughts, reactions or opinion on something.” A letter is not a memo, nor is a memo a letter. A memo can call people to action or broadcast a bit of timely news. With memo writing, shorter is better. Approaches to Memo Writing Decide if it’s to be persuasive or informative. A persuasive memo engages the reader’s interest before issuing a directive, where as an informative memo outlines the facts and then requests the reader’s actions. Clearly state the purpose of communication in the subject line. Make the subject line as descriptive as possible so the reader understands the intent. A memo simply titled “Vacation Time” might appear to be good news – until the document explains that vacation time won’t be granted unless first requested in writing. Thus, a better memo title might be “New Vacation Time Request Policy". Write memos with purpose and make that purpose known in the first paragraph. Outline the purpose and the desired action in the memo’s first paragraph. Readers will become conditioned to the importance of a memo and gain that knowledge as soon as they open it. K.I.S.S. – Keep It Simple, Silly. This means that the topic details should be concise, with clear directives and contacts for follow-up. If it’s a complex topic extending into multiple pages, still keep the language as direct as possible, add headings or bullets to guide the reader and conclude with a summary paragraph of key points. PARTS OF A MEMO HEADING The heading segment follows this general format: TO: (readers' names and job titles) CC: (any people you are copying the memo to) FROM: (your name and job title) DATE: (complete and current date) SUBJECT: (what the memo is about, highlighted in some way) OPENING SEGMENT The gist of a memo should occur in the opening sentences/paragraphs. It's a good idea to include some information about the context, a task statement and perhaps a purpose statement. SUMMARY SEGMENT If your memo is longer than a page, you may want to include a separate summary segment. This segment provides a brief statement of the key recommendations you have reached. These will help your reader understand the key points of the memo immediately. DISCUSSION SEGMENT The discussion segments are the parts in which you get to include all the details that support your ideas. Keep two things in mind: 1. Begin with the information that is most important. This may mean that you will start with key findings or recommendations. 2. For easy reading, put important points or details into lists rather than paragraphs when possible. CLOSING SEGMENT After the reader has read your information, you want to close with a courteous ending stating what action you want your reader to take. For example, you might say, "I will be glad to discuss this recommendation with you during our meeting on Tuesday and follow through on any decisions you make." NECESSARY ATTACHMENTS Attach necessary lists, graphs, tables, etc. at the end of your memo. Be sure to refer to your attachments in your memo and add a notation about what is attached below your closing, like this: Attached: Several Complaints about Product, January - June 2007 What is an Email? “A system for sending and receiving messages electronically over a computer network, as between personal computers.” Email is shorthand term meaning Electronic Mail. Email is much the same as a letter, only that it is exchanged in a different way. The first thing you need to send and receive emails is an email address. When you create an account with an Internet Service Provider you are usually given an email address to send from and receive emails. If this isn't the case you can create an email address / account at web sites such as yahoo, hotmail and gmail. Anatomy of an E-Mail Message • The header of an email includes the From:, To:, Cc: and Subject: fields. So you enter the name and address of the recipient in the From: field, the name and address of anyone who is being copied to in the Cc: field, and the subject of the message obviously in the Subject: field. • The part below the header of the email is called the body, and contains the message itself. • Spelling the correct address is critical with an email. Like with a normal postal letter, if you get the address wrong it won't go the correct receiver. If you send an email to an address which doesn't exist the message will come back to you as a Address Unknown error routine. Resume or Curriculum Vitea A summary of your academic and work history Resume sections • • • • • • • • Your name Your address Resume objective Profile or summary of qualifications Employment history Education Skills Activities Basic Resume Formats 1. Chronological: The chronological resume format lists work experience first, beginning with your most recent (or current) job. It then continues with your education and concludes with extra skills and interests that may contribute to your ability to perform the job. Basic Resume Formats 2. Skills Format: The skills resume begins with a list of skills that relate to the job for which you are applying. The skills resume format is exceptionally useful when: 1) you are applying for a job in a different field than your work experience, 2) you have large gaps in your work experience or 3) you have little or no paid work experience. Basic Resume Formats 3. The Combination or Functional Format: This format is useful in highlighting skills that are relevant to a particular field of work. It is best used to demonstrate improvement and achievement within a specific field of work. Cover Letter Never send a resume without a cover letter! Purposes of a Cover Letter • Used when responding to specific, advertised openings or expressing interest in organization • Explains why you are sending the resume, how you learned about company or position • Convinces reader to look at your resume • Calls attention to important attributes of your background • Shows your personality, attitude, enthusiasm and communication skills Do’s & Don’ts of Cover Letters • Don’t repeat information found in resume • Do Sum-up important qualities, areas of expertise, and motivation about field or position of interest • Do include information about availability • Do explain shortcomings or gaps in work experience in history • Do try to keep the cover letter to one page; however, two pages are acceptable, especially when reflective of extensive work experience General Structure of the Cover Letter 1. Opening paragraph: State why you are writing, how you learned of the organization or position, and basic information about yourself 2. Main Body paragraph: Tell why you are interested in employer or type of work. Demonstrate that you know enough about the employer or position and relate your background to the employer or position. Mention specific qualifications that make you a good fit for the employer’s needs. Refer to the fact that your resume is enclosed. 3. Closing paragraph: Indicate you would like opportunity to interview for a position or to talk with employer to learn more about career opportunities. State how you will follow up on the letter, such as calling the company/employer. Offer to provide employer with additional information such as certificates, references, etc. 4. Thank the employer for his or her consideration of your letter/attached resume (could be a brief 4th paragraph). How to Use a Dictionary? Dictionaries are books that list all the words in a language. With a Dictionary, you can learn: -How to spell a word -What a word means -How to say a word -What part of speech a word is -How many syllables are in a word -Whether or not to capitalize a word -How to abbreviate a word (example: USA) -Meanings of prefixes and suffixes for a word VOCABULARY • Headword- the word you are looking up. It is always in bold type. • Entry- the information on the word you are looking up. • Pronunciation- tells you how to say the word. Found in (parentheses). • Part of speech- tells you how the word is used in a sentence (n=noun, v=verb, adj=adjective, adv=adverb). VOCABULARY • Definition- all possible meanings for the word. Many words have more than one meaning. • Examples- Shows you how the word is used in a sentence. Usually found in italics. • Etymology- this tells you the history of the word, and what language it came from. This is a definition for flag: flag /flæg/ 1. noun A piece of cloth with a pattern or symbol of a country, an organization, etc. 2. verb To stop, or to signal. We flagged down the police officer. What is a Thesaurus? A thesaurus is a book that can help you find words with the same or similar meanings. (No, a thesaurus is NOT a kind of dinosaur) Why use a Thesaurus? • To avoid using the same word over and over • To find a word that has the same or similar meaning • To find the opposite of a word • To learn new words • To make your writing more interesting or exciting How do I use a Thesaurus? A thesaurus is arranged very much like a dictionary. • Alphabetical order • Guide words • Entries A thesaurus entry usually has: • Headword in BOLD • Part of speech • Synonyms (words with same or similar meaning) • Antonyms (words with opposite meanings) Effective Presentations Skills Definitions Presentation • “Something set forth to an audience for the attention of the mind “ Effective • “…producing a desired result” Effective Presentations • • • • • • Control Anxiety – Don’t Fight It Audience Centered Accomplishes Objective Fun For Audience Fun For You Conducted Within Time Frame Why Give A Presentation? Three Main Purposes 1. Inform 2. Persuade 3. Educate Planning A Presentation 1. Determine Purpose 2. Assess Your Audience – “Success depends on your ability to reach your audience.” – Size – Demographics – Knowledge Level – Motivation Planning A Presentation 3. Plan Space – Number of Seats – Seating Arrangement – Audio/Visual Equipment – Distracters 4. What Day and Time? – Any Day! – Morning More Planning 5. Organization – Determine Main Points (2-5) – Evidence – Transitions – Prepare Outline Organizing Your Presentation Organizational Patterns • Topical • Chronological • Problem/Solution • Cause/Effect Presentation Outline • • • • Keyword Reminders Conversational Flow Flexibility More Responsive to Audience Recap Objectives: • Review of the Course Contents Grammar Writing (Composition) Message Composition Presentation Skills References • http://www.rong-chang.com/grammar/punctuation.html • http://www.uottawa.ca/academic/arts/writcent/hypergramm ar/usetense.html • http://www.englishpage.com/verbpage/verbtenseintro.html • http://www.grammarbook.com/grammar/subjectVerbAgree.a sp • http://www.ego4u.com/en/cram-up/grammar/word-order • http://www.learnenglish.de/grammar/determinertext.htm • http://chompchomp.com/structure01/structure01.20.b.htm • http://faculty.ncwc.edu/lakirby/English%20090/prewriting_st rategies.htm • http://xiamenwriting.wikispaces.com/Pre-writing+Techniques • http://www.victoria.ac.nz/llc/academic-writing/ • http://www4.caes.hku.hk/acadgrammar/essay/section1/Essa yTys.htm