CCSS Assessment Example, ELA Grade 11 Title of Performance

advertisement

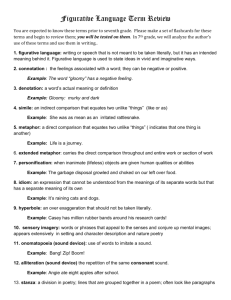

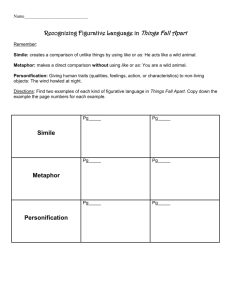

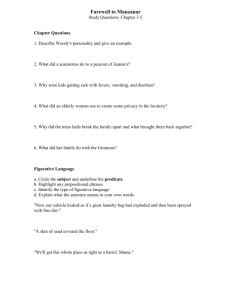

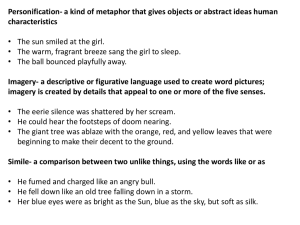

CCSS Assessment Example, ELA Grade 11 Title of Performance Task: Interdisciplinary Writing: Biodiesel Production Grade Level: 11 In order to complete the assessment, students must: 1. Compose, revise, and edit text in proper format 2. Write a text in support of an argument in response to texts read 3. Address Purpose and Audience (setting a context – topic, question(s) to be answered, and establishing a focus/thesis/claim 4. Organize and Develop Ideas using a structure consistent with purpose (providing overall coherence using organizational patterns and transitions to connect and advance central ideas 5. Provide supporting evidence/details/elaboration consist with focus/thesis/claim 6. Use Language Effectively (including word choice, sentence variety, precise/nuanced language, domain-specific language, and voice) 7. Apply Conventions of Standard English Standards Assessed with this Task Writing Standards: 11-12.W.1. Write arguments (a-e) 11-12.W.4. Produce writing in which the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience 11-12.W.5. Strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience 11-12.W.7. Perform short, focused research projects and more sustained research; synthesize multiple authoritative sources on a subject to answer a question or solve a problem (formative) 11-12.W.8. Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, using advanced searches effectively; assess the strengths and limitations of each source in terms of the task, purpose and audience; integrate information into the text selectively to maintain the flow of ideas, avoiding plagiarism and overreliance on any one source and following a standard format for citation. 11-12.W.9. Write in response to literary or informational sources, drawing evidence from the text to support analysis and reflection as well as to describe what they have learned. Language Standards: 11-12.L.1. Observe conventions of grammar and usage 11-12.L.2. Observe conventions of capitalization, punctuation, and spelling 11-12.L.3. Make effective language choices. 11-12.L.6. Use grade-appropriate general academic vocabulary and English language arts– specific words and phrases taught directly and gained through reading and responding to texts Title: Interdisciplinary Writing: Biodiesel Production Task Summary: In Phase 1, students prepare for writing by reading source material provided, locating at least one additional source*, and organizing notes. Prewriting/planning involves finding additional information on the topic and writing notes in graphic organizers. Students decide on a claim, as well as explore supporting and opposing arguments. In Phase 2, students write a letter either in support of or in opposition to biodiesel production based on the material presented in the two newspaper articles and evidence from the additional source. *Novice version of task would provide the third source for students or be limited to two sources Phase 1 1. Students read source material provided 2. Students locate additional source material through independent research 3. Students make notes in support of and in opposition of biodiesel production in graphic organizers Phase 2 1. Students draft letter using evidence gathered from source materials 2. Revise letter using evidence gathered from articles Actual prompt for student The purpose of this assessment is to determine how well you can establish and support a claim about a specific topic. In Phase 1, you will read two short articles about a controversial issue, take a position on the issue, and find at least one additional resource to support your position. You must support your position with relevant information from all of the source materials. In Phase 2, you will draft and revise your persuasive letter. Your score will be based on the following criteria: 1. Position-Did you take a clear position on the issue? 2. Comprehensiveness-Did you use information from all three sources to sy]upport claims or counter claims? 3. Support-Did you support your position with accurate and relevant information? 4. Organization-Did you organize your ideas in a logical and effective manner so that your audience can understand and follow your thinking? 5. Clarity and Fluency-Did you express your ideas clearly and fluently using your own words? 6. Did you edit for grammar, usage, and mechanics? Title of Performance Task: Study-Listen-Apply Grade Level: Grade 11 In order to complete the assessment, students must: 1. Review a video lecture listening for relevant information and taking notes 2. Analyze the purpose of information presented in diverse media and formats (video and text documents related to the topic) and evaluate the motives behind its presentation 3. Read informational text sources related to the video lecture 4. Summarize central ideas 5. Interpret impact or intent of figurative meanings of words and phrases used in context. Standards Assessed with this Task Reading Standards: 11-12.RI.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze how an author uses and refines the meaning of a key term or terms over the course of a text Language Standards: 11-12.L.5: Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings. Speaking and Listening Standards: 11-12.SL.2: Integrate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) in order to make informed decisions and solve problems, evaluating the credibility and accuracy of each source and noting any discrepancies among the data. Title: Study-Listen-Apply Task Summary: Students are presented with a 5-7 minute video lecture related to a general education [English language arts, mathematics, history/social studies, science/technical subjects] course and supplementary [text-based and/orgraphical] materials that [illustrate, explain, expand upon, and/or disagree with] the preceding lecture; students are asked short response comprehension and application questions in order to elicit evidence of skills related to reading, speaking and listening, and language that are required for processing new content in college courses. Study-Listen-Apply - General Instructions This task is designed to simulate an experience you may have as you encounter new information in the college courses you take. In this task you will do the following: 1. Watch a brief video lecture. 2. Read and examine documents related to the lecture. 3. Take notes about your understanding of the documents and lecture. You may take notes on the lecture, but you will only be able to watch the lecture once. You may use the provided documents and your notes to help you to answer multiple choice and short response comprehension and application questions. Text of Lecture (accompanying lecture slides not included): Today we’re going to investigate the relationship between literal language and figurative language. When we use language literally, we say what we mean directly. But when we use language figuratively, we express ourselves indirectly—we use something that’s not really here, in order to explain an idea, a feeling, or an experience. Language is, by definition, something that we all share. If I ask you to [first slide] close the door because it’s noisy outside, it’s probably very clear to you what I’m talking about. We all know what a door is, and, if we’re sitting in a room together, we know which particular door I’m talking about. For communication to happen, we have to have this shared knowledge. We have to all share the common reference, “door.” As long as we stick to things like doors and can all point to the same thing, direct language works just fine. But we have a lot more to say to each other than just things that we can easily recognize. There are many things that we want to talk about that are not as obvious as doors. How do we refer to things like feelings, that occur inside of us? How do we refer to ideas that that we may have thought up ourselves and haven’t told anyone yet? How do we make each other understand what our intimate experience of life is like? This is where we make use of figurative language. We use figurative language to talk about things that are not directly before our eye and ears. We use figurative language to share the unique way that we each experience the world; and we use figurative language to look deeply at how things work. Using figurative language is something we instinctively know how to do. When we say [next slide] “It’s raining cats and dogs,” we generally don’t literally mean that cats and dogs are falling from the sky; we mean to say that it’s raining really hard. To use cats and dogs to describe the rain is to use figurative language. We all know how to do this. Our question for today is why we might use figurative language. In order to understand this, we need first to understand something about the way language works. Again, this is something that we do all the time. If we say that [next slide] someone’s heart is an ice cube, we don’t literally mean that there is a block of ice where we would expect cardiac muscle—but we say that to try to describe something that we feel but can’t necessarily see. Sometimes we even feel that the word we want doesn’t exist. In these cases, we have to choose something that we can use to describe it through resemblance. Let’s look at a small example of figurative language in poetry. The poet Emily Dickinson writes, [next slide] “hope” is the thing with feathers--That perches on the soul We have to first figure out what image Dickinson is using. What is the “thing with feathers?” We know from the poem that whatever it is, it perches. So when we put these two things together, something that has feathers that perches, we might reasonably arrive at the image of a bird. So now we could think of the poem as saying something like, “Hope is a bird.” By attributing to the idea of hope the characteristics of a bird, something we might not normally do, Dickinson is using the kind of figurative language that is called metaphor. A metaphor attributes something familiar to something unfamiliar through resemblance, in order to make the unfamiliar thing more clear. If a metaphor works, then the thing that’s being described becomes recognizable. In the process, we might find that through a metaphor, we bring something new into the public domain—we can allow others to “think” our thoughts. But why not talk about hope directly? Hope is something that we all have, that we all feel inside ourselves. But nonetheless, it’s difficult to say clearly what it is. Hope is not something that we can see, like a door to a classroom. The door is something we all share; but the way you and I hope and what we hope for might be very different. So if we want to talk about hope, we need to try to find something that that we can use to see it together. Hope is a feeling; we can’t see it. But a bird is something concrete. We can see it. This is what a metaphor does. It carries over a feeling or an idea, something felt intimately by someone, into the public view, through the use of something in the world that we can all recognize. But now we have to ask what it is about a bird that helps us to understand the idea of hope better. Here is where the idea of resemblance comes in. Birds, unlike people, can fly. If a bird wants to go from a branch to the roof of a house, it spreads its wings, and flies there, seemingly effortlessly. When we hope for something, we imagine some place in our lives to which we haven’t arrived yet. In our imagination, we’re not restricted, even though in our bodies we are. Hope can “fly” to where we want to be in life, before we can actually get there. So Emily Dickinson invites us to see hope in the form of a bird, who flies ahead of us into the life we haven’t lived yet. We can’t see hope, we might hope for different things, but Emily Dickinson might give us a way to imagine it together. “hope” is the thing with feathers--That perches on the soul Metaphor operates through resemblance. Emily Dickinson’s experience of hope can be communicated in the poem because it resembles a bird, which is something that we all have experience with. We grasp the thing being described because it works like something we already know. Using the familiar object, we reconstruct in our own minds the idea that the writer is trying to convey. In order for us to understand a metaphor correctly, we need to be able to distinguish between the two levels of reality that it creates. When Shakespeare says, [next slide] “there’s daggers in men’s smiles,” we know right away that the men whom he’s talking about don’t have knives in their mouths. We know that the daggers aren’t here the way the smiles are here. The smiles are on the literal level. But we use the daggers in order to learn something about smiles: that smiles are not always sincere; that smiles could hide an evil intention. With Shakespeare’s metaphor, we might even feel the danger in the smile he describes. If we take it even further, we could understand from Shakespeare’s metaphor the idea that things are not always what they seem to be. The smile is literal, it’s what we see. The daggers are figurative: we use our familiarity with daggers, to understand what Shakespeare wants to say about a smile. To summarize: When we speak literally, we speak about things that we all know, and that we share together. We can think of figurative language as a technology that we use to take something that all of us, or at least most of us, can share, in order to precisely describe something that is not easily sharable, such as feelings, complex ideas, and our unique ways of experiencing the world. Supplementary Materials The novelist Marcel Proust writes, “An hour is not merely an hour, it is a vase full of scents and sounds.” We can see here how the use of figurative language causes words to diverge from their normal meanings in order to tell us something new. When we use a word ordinarily, we are speaking on the literal level. Here, Proust uses the word “vase” in an unordinary way, and in doing so, he assigns it a new meaning. We know that Proust is not talking about a “real” vase. Rather, he is using the word “vase” to expand upon our understanding of what an hour is. The literary critic I.A. Richards uses the terms “vehicle” and “tenor” to discuss the split in meaning that the use of figurative language creates. In our example, the vase is not here as itself: rather, it is used as the vehicle that will be used to give us a new understanding of what an hour is. The hour here, is the thing that is being described, and in Richards’s terminology, it is the tenor. The vehicle in a metaphor must be something that most readers have experience with. A vehicle, “takes” the reader all the way through to the new understanding. The “vase full of scents and sounds” becomes our new idea of an hour. In everyday speech, we often use figurative language without realizing it. When an offer comes with “no strings attached,” for example, the strings serve as the vehicle for understanding the tenor, or real meaning, which is that the offer comes with no further obligation. Sample of selected and constructed response questions Conventional Multiple-Choice Questions – other selected response item types could be used 1. Which of the following is the best example of the literal use of language? A. “Between Mobile and Galveston there is / A great garden filled with roses” (Guillaume Apollinaire)* B. “Love makes thinking dark” (Laura Riding) C. “The soul selects her own society / then shuts the Door—“ (Emily Dickinson) D. “I kissed the summer dawn.” (Arthur Rimbaud) 2. Which of the following situations would most likely provide the occasion for using a metaphor? A. The representative of a jury detailing to a judge the reasons for a conviction. B. Someone asking for, and getting, directions to a restaurant. C. Writing an entry in an encyclopedia about tropical fish. D. A physicist, explaining to non-scientists, the structure of atoms.* 3. Choose the response that best describes the following excerpt from Claude McKay’s poem, The Harlem Dancer. She sang and danced on gracefully and calm, The light gauze hanging loosely about her form. To me she seemed a proudly-swaying palm Grown lovelier for passing through a storm. A. The main idea is that the light gauze resembles a palm tree. B. The speaker would like us to understand the particular way in which he sees a woman dancing.* C. The main idea is that people become stronger by weathering the storms of life. D. The speaker would like us to understand how a storm can be graceful and calm. Read the following excerpt from William Shakespeare’s As You Like It and answer the following two questions. All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, 4. Which of the following would best describe one of the ideas in Shakespeare’s metaphor? A. The theater offers many different possibilities for actors and actresses. B. A good play will have many different actors entering and exiting. C. Because the world itself is a great stage, there is no need to produce plays. D. We play many different roles over the course of our lives.* 5. In Shakespeare’s metaphor: A. The tenor is daily life, and the vehicle is the theater.* B. The tenor is the theater, and the vehicle is daily life. C. The tenor is the exits and entrances, and the vehicle is “one man.” D. The tenor is the stage, and the vehicle is the men and women. Constructed response: In complete sentences, thoroughly answer the following questions related to the video and the document using examples/supporting evidence from each source when possible. 1. Why do we use literal and figurative language when we communicate? Give one example from the video lecture and one example from the documents you read to illustrate what you learned from the two sources. You may use your notes from watching the video to help you with your answer. 2. Which source presented the information about literal and figurative language more clearly in your opinion? Why/How? Defend your answer. Title of Performance Task: Common Theme (War) Grade Level: 11 In order to complete the assessment, students must: 1. Review two sources of information to critically analyze each piece for relevant information 2. Synthesize information from multiple sources and across content areas to determine perspective for argument 3. Cite relevant information from sources to support argument 4. Organize ideas to communicate effectively 5. Use domain-specific vocabulary (Language Use) 6. Observe conventions of grammar, usage, and mechanics appropriate for grade level Standards Assessed with this Task Writing Standards: 11-12.W.2. Write informative/explanatory texts (a-e) 11-12.W.4. Produce writing in which the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience 11-12.W.5. Strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. 11-12.W.7. Perform short, focused research projects and more sustained research; synthesize multiple authoritative sources on a subject to answer a question or solve a problem. 11-12.W.8. Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, using advanced searches effectively; assess the strengths and limitations of each source in terms of the task, purpose and audience; integrate information into the text selectively to maintain the flow of ideas, avoiding plagiarism and overreliance on any one source and following a standard format for citation. 11-12.W.9. Write in response to literary or informational sources, drawing evidence from the text to support analysis and reflection as well as to describe what they have learned. Language Standards: 11-12.L.1. Observe conventions of grammar and usage 11-12.L.2. Observe conventions of capitalization, punctuation, and spelling 11-12.L.3. Make effective language choices. a. Write and edit work so that it conforms to the guidelines in a style manual. 11-12.L.6. Use grade-appropriate general academic vocabulary and English language arts– specific words and phrases taught directly and gained through reading and responding to texts Actual prompt for student This task is designed to measure your ability to read, analyze, and synthesize information from different sources and perspectives. You will be provided with a “Document Library” consisting of several types of documents. In addition, you will be asked to locate at least one additional resource to support your informational/explanatory essay. Read all of the documents on the following pages, conduct additional research, and write an essay response based on the scenario described below. You may use the margins to take notes as you read and scrap paper to plan your response. Please write the essay solely on the basis of the scenario below. Although you may not be familiar with some of the topics covered, you should be able to write the essay by carefully using and thoughtfully reflecting on the information you have analyzed. ELA Performance Task Example (Common Theme: War) Performance Task Scenario Your English and Social Studies teachers have teamed up to teach a joint unit on war. As a project for this joint unit, you have been asked to read a variety of documents concerning war in order to determine different perspectives - whether they glorify, justify or condemn war. Your final task will be to write an essay that states how you now see war, citing evidence from the documents used to explain your position. Texts Document 1: Jessie Pope, “Who’s For the Game” (c. 1916) Who’s for the game, the biggest that’s played, 1 The red crashing game of a fight? 2 Who’ll grip and tackle the job unafraid? 3 And who thinks he’d rather sit tight? 4 Who’ll toe the line for the signal to ‘Go!’? 5 Who’ll give his country a hand? 6 Who wants a turn to himself in the show? 7 And who wants a seat in the stand? 8 Who knows it won’t be a picnic—not much— 9 Yet eagerly shoulders a gun? 10 Who would much rather come back with a crutch 11 Than lie low and be out of the fun? 12 Come along, lads— but you’ll come on all right— 13 For there’s only one course to pursue, 14 Your country is up to her neck in a fight, 15 And she’s looking and calling for you. 16 Document 2: George Cruickshanks, “The Recruit’s Journey” (date unknown) Source: CartoonStock, www.cartoonstock.com Document 3: George Harcourt, The Boer War (1900) Document 4: Woodrow Wilson, address to Congress, April 2, 1917 It is a distressing and oppressive duty, gentlemen of the Congress, which 1 I have performed in thus addressing you. There are, it may be, many 2 months of fiery trial and sacrifice ahead of us. It is a fearful thing to 3 lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and 4 disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. 5 But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the 6 things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for 7 democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a 8 voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small 9 nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free 10 peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the 11 world itself at last free. To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our 12 fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the 13 pride of those who know that the Phase has come when America is 14 privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave 15 her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God 16 helping her, she can do no other. 17 Document 5: Wilfred Owen, “Dulce Et Decorum Est” (c. 1918) Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, 1 Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, 2 Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs 3 And towards our distant rest began to trudge. 4 Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots 5 But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; 6 Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots 7 Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines1 that dropped behind. 8 Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling, 9 Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; 10 But someone still was yelling out and stumbling 11 And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime… 12 Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light, 13 As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. 14 In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, 15 He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning. 16 If in some smothering dreams you too could pace 17 Behind the wagon that we flung him in, 18 And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, 19 His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin; 20 If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood 21 Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, 22 Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud 23 Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues— 24 My friend, you would not tell with such high zest 25 To children ardent for some desperate glory, 26 The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est 27 Pro patria mori. 28