Revised Manuscript - 09-01-2015 FINAL-1

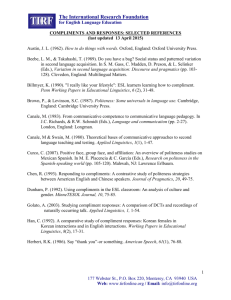

advertisement