Liberty, Lazurus, immigrants documents - elementary

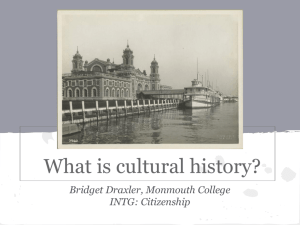

advertisement

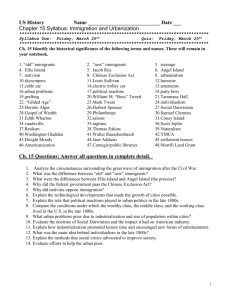

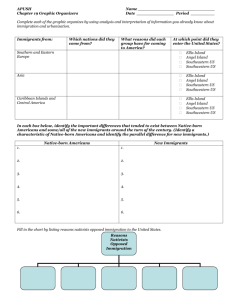

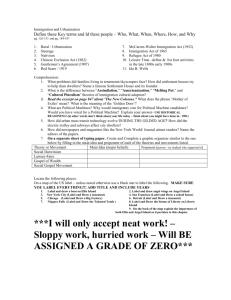

From Jewish Women’s Archive http://jwa.org/womenofvalor/lazarus Introduction Emma Lazarus, 1849 – 1887 Full image | Source "Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." Emma Lazarus's famous lines captured the nation's imagination and continues to shape the way we think about immigration and freedom today. Written in 1883, her celebrated poem, "The New Colossus," is engraved on a plaque in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. Over the years, the sonnet has become part of American culture, inspiring everything from an Irving Berlin show tune to a call for immigrants' rights. One of the first successful Jewish American authors, Lazarus was part of the late nineteenth century New York literary elite and was recognized in her day as an important American poet. In her later years, she wrote bold, powerful poetry and essays protesting the rise of antisemitism and arguing for Russian immigrants' rights. She called on Jews to unite and create a homeland in Palestine before the title Zionist had even been coined. Full image | Source Full image | Source As a Jewish American woman, Emma Lazarus faced the challenge of belonging to two often conflicting worlds. As a woman she dealt with unequal treatment in both. The difficult experiences lent power and depth to her work. At the same time, her complicated identity has obscured her place in American culture. From The Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island Website http://www.libertystatepark.com/emma.htm Statue of Liberty National Monument Emma Lazarus’ Famous Poem A poem by Emma Lazarus is graven on a tablet within the pedestal on which the statue stands. The New Colossus Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. "Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!" History of Liberty State Park The Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island Photos On the New York Harbor, less than 2,000 feet from the Statue of Liberty, Liberty State Park has served a vital role in the development of New Jersey's metropolitan region and the history of the nation. During the 19th and early 20th centuries the area that is now Liberty State Park was a major waterfront industrial area with an extensive freight and passenger transportation network. This network became the lifeline of New York City and the harbor area. The heart of this transportation network was the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal (CRRNJ), located in the northern portion of the park. The CRRNJ Terminal stands with the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island to unfold one of this nation's most dramatic stories: the immigration of northern, southern, and eastern Europeans into the United States. After being greeted by the Statue of Liberty and processed at Ellis Island, these immigrants purchased tickets and boarded trains, at the CRRNJ Terminal, that took them to their new homes throughout the United States. The Terminal served these immigrants as the gateway to the realization of their hopes and dreams of a new life in America. Today, Liberty State Park continues to serve a vital role in the New York Harbor area. As the railroads and industry declined, the land was abandoned and became a desolate dump site. With the development of Liberty State Park came a renaissance of the waterfront. Land with decaying buildings, overgrown tracks and piles of debris was transformed into a modern urban state park. The park was formerly opened on Flag Day, June 14, 1976, as New Jersey's bicentennial gift to the nation. Most of this 1,122 acre park is open space with approximately 300 acres developed for public recreation. 1492 Thou two-faced year, Mother of Change and Fate, Didst weep when Spain cast forth with flaming sword, The children of the prophets of the Lord, Prince, priest, and people, spurned by zealot hate. Hounded from sea to sea, from state to state, The West refused them, and the East abhorred. No anchorage the known world could afford, Close-locked was every port, barred every gate. Then smiling, thou unveil'dst, O two-faced year, A virgin world where doors of sunset part, Saying, "Ho, all who weary, enter here! There falls each ancient barrier that the art Of race or creed or rank devised, to rear Grim bulwarked hatred between heart and heart!" Emma Lazarus From: Jewish Virtual Library http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/lazarus.html Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) By Diane Lichtenstein "Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free," proclaims the "Mother of Exiles" in Emma Lazarus's sonnet "The New Colossus." Her best-known contribution to mainstream American literature and culture, the poem has contributed to the belief that America means opportunity and freedom for Jews, as well as for other "huddled masses." Through this celebration of the "other," Lazarus conveyed her deepest loyalty to the best of both America and Judaism. Born on July 22, 1849, Lazarus was the fourth of Esther (Nathan) and Moses Lazarus's seven children. She grew up in New York and Newport, Rhode Island, and was educated by private tutors with whom she studied mythology, music, American poetry, European literature, German, French, and Italian. Her father, who was a successful sugar merchant, supported her writing financially as well as emotionally. In 1866, when Emma was only seventeen, Moses had Poems and Translations: Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen printed "for private circulation." Daughter Emma dedicated the volume "To My Father." Soon after Poems and Translations was published, Lazarus met Ralph Waldo Emerson. The two corresponded until Emerson's death in 1882. During the early years of their relationship, Lazarus turned to Emerson as her mentor, and he in turn praised and encouraged her writing. In 1871, when she published Admetus and Other Poems, she dedicated the title poem "To My Friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson." Despite his support, Emerson failed to include any of Lazarus's poetry in his 1874 anthology, Parnassus, but he did include authors such as Harriet Prescott Spofford and Julia C.R. Dorr. Lazarus responded with an uncharacteristically angry letter and subsequently modified her idealized image of Emerson. However, student and mentor obviously reconciled; in 1876, Lazarus visited the Emersons in Concord, Massachusetts. Admetus and Other Poems includes "In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport" and "How Long" as well as translations from the Italian and German (Goethe and Heine). "In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport" echoes in form and meter Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport." Yet where Longfellow's meditation closes with "the dead nations never rise again," Lazarus's reverie concludes by announcing that "the sacred shrine is holy yet." "In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport" is one of Lazarus's earliest creative expressions of a Jewish consciousness. "How Long" is significant because its proclamation of the need for a "yet unheard of strain," one suitable to prairies, plains, wilderness, and snow-peaked mountains places Lazarus among those mid-nineteenth century American writers who wanted to create literature that did not depend on British outlines. Lazarus published her next book, Alide: An Episode of Goethe's Life, in 18 74. Her only novel, Alide is based on Goethe's own autobiographical writings and focuses on a love affair between the young Goethe and a country woman. The lovers part at the end, because the poet must be free to fulfill his "sacred office." Lazar-us's only other piece of fiction, a story titled "The Eleventh Hour," was published in 1878 in Scribner's. The story raises questions about the needs and rights of the artist, like Alide, and about the status of American art, like "How Long." In 1876, Lazar-us privately published The Spagnoletto, a tragic verse drama. Throughout the 1870s and early 1880s, Lazarus's poems appeared in American magazines. Among these are "Outside the Church" (1872) in Index; "Phantasmagoria" (1876) and "The Christmas Tree" (1877) in Lippincott's; "The Taming of the Falcon" (1879) in the Century; and "Progress and Poverty" (18 8 1) in the New York Times. Lazarus's most productive period was the early 1880s. In addition to numerous magazine poems, essays, and letters, she published a highly respected volume of translations, Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine, in 1881, and Songs of a Semite: The Dance to Death and Other Poems, in 1882. This was also the period in which Lazarus most obviously spoke out as self-identified Jew and American writer simultaneously. Until this period, Lazarus's "interest and sympathies were loyal to [her] race," but, as she explained in 1877, "my religious convictions ... and the circumstances of my life have led me somewhat apart from my people." Although her family did belong to the Sephardic Shearith Israel synagogue in New York, and she did write "In the Jewish Synagogue in Newport" when she was young, it appears that learning of the Russian pogroms in the early 1880s kindled Lazarus's commitment to Judaism. This change in attitude is evident in her writing, as well as in her work with the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society-meeting Eastern European immigrants on Wards Island-and in her efforts to help establish the Hebrew Technical Institute and agricultural communities for Eastern European Jews in the United States. Songs of a Semite was published by the American Hebrew. The title, as well as many of the poems in the collection, publicly proclaimed Lazarus's identity as a Jewish poet. In that role, Lazarus battled against both anti-Semitic non-Jews and complacent Jews. In "The Banner of the Jew," she urged "Israel" to "Recall today / The glorious Maccabean rage," and she reminded readers that "With Moses's law and David's lyre" Israel's "ancient strength remains unbent." And in The Dance to Death, a poetic dramatization of Richard Reinhard's 1877 prose narrative Der Tanz zum Tode, Lazarus celebrated the courage and faith of the Jews who were condemned to die in Nordhausen, Germany, in 1349 for allegedly causing the plague. The Dance to Death was dedicated to George Eliot, "who did most among the artists of our day towards elevating and ennobling the spirit of Jewish nationality" with her novel Daniel Deronda. Lazarus published Songs of a Semite in the same year that she adopted a more public Jewish identity in the realm of American magazines, particularly in the Century. Three essays published in that magazine over a ten-month period attest to Lazar-us's concerns. In the first, "Was the Earl of Beaconsfield a Representative Jew?" (April 1882), Lazarus offered an ambivalent portrait of Benjamin Disraeli; she defined "representative" as embodying the best as well as the worst of Jewish traits. In the second essay, "Russian Christianity vs. Modem Judaism" (May 1882), Lazarus included a personal plea for informed understanding of Russian Jews and their situation. And in the third essay, "The Jewish Problem" (February 1883), she observed that Jews, who are always in the minority, "seem fated to excite the antagonism of their fellow countrymen." To this problem she offered a solution: the founding of a state by Jews for Jews in Palestine. Lazarus promoted Zionism throughout the 1880s. Although Lazarus had published occasionally in the Jewish press, she became a regular contributor to the American Hebrew in the early 1880s. This weekly, edited by Philip Cowan, printed "Judaism the Connecting Link Between Science and Religion" and "The Schiff Refuge" in 1882, "An Epistle to the Hebrews" in 1882-1883, "Cruel Bigotry" in 1883, and "The Last National Revolt of the Jews" as well as "M. Renan and the Jews"-an essay, which won first prize in a contest sponsored by the Philadelphia Young Men's Hebrew Association-in 1884. In "An Epistle to the Hebrews," a series of fifteen open letters that appeared between November 1882 and February 1883, Lazarus suggested that assimilated American Jews should recognize their privileged status as well as their vulnerability in America, that all Jews should understand their history in order not to be misled by anti-Semitic generalizations, and that Eastern European Jews should emigrate to Palestine. At the same time that Lazarus was writing more self-consciously as a Jew, she was also writing as an American. Her 1881 essay "American Literature" (Critic) defended American literature against the charge that America had no literary tradition and that America's poets had left no mark. "American Literature" was followed by "Henry Wadsworth Longfellow" (American Hebrew) and the eulogy "Emerson's Personality," both published in 1882. The latter appeared in the Century, three months after "Was the Earl of Beaconsfield a Representative Jew?" and two months after "Russian Christianity vs. Modern Judaism." Lazarus also published the poem "To R.W.E." in 1884 (Critic). Lazarus wrote "The New Colossus" in 1883 "for the occasion" of an auction to raise money for the Statue of Liberty's pedestal. The poem was singled out and printed in the Catalogue of the Pedestal Fund Art Loan Exhibition at the National Academy of Design because event organizers hoped it would "awaken to new enthusiasm" those working on behalf of the pedestal. In the following year, Lazarus published the essay "The Poet Heine" in the Century. Lazarus explained her fascination with Heine, born a Jew and later baptized and educated as a Catholic: "A fatal and irreconcilable dualism formed the basis of Heine's nature.... He was a Jew, with the mind and eyes of a Greek." Lazarus admired Heine's ability to understand the "internal incongruity" of his mind as well as his Jewish "pathos" and worldly sensibility. Lazarus traveled to Europe twice, the first time in 1883. During her stay in England and France, she met Robert Browning, William Morris, and Jewish leaders. Her essay "A Day in Surrey with William Morris" (the Century, 1886) paints a positive portrait of the English socialist. Noting that Morris's "extreme socialistic convictions" elicited criticism, Lazarus explained that English inequalities were more "glaring" than American ones and therefore more in need of dramatic reform. Lazarus's second trip to Europe was a longer one, lasting from May 1885 until September 1887. According to her sister Josephine Lazarus's biographical sketch, Emma "decided to go abroad again as the best means of regaining composure and strength" after Moses Lazarus died in March 1885. This journey included visits to England, France, Holland, and Italy. Lazarus returned to New York very ill, probably with cancer. She died two months later, on November 19, 1887. Two of Lazarus's sisters, Mary and Annie, published The Poems of Emma Lazarus, I and II posthumously, in 1888. Volume I contains the biographical sketch written by sister Josephine. In the same year, the sketch also appeared in the Century. Volume 11 includes her final work, "By the Waters in Babylon, Little Poems in Prose," which had previously appeared in the Century in March 1887. This set of Prose poems suggests that Lazarus was exploring new directions for her art. Volume 11 also contains translations of "Hebrew poets of mediaeval Spain," Solomon Ben Judah Gabirol, Abul Hassan Judah Ben Ha-Levi, and Moses Ben Esra. Lazar-us's work received consistently positive reviews. By the late 1870s and 1880s, American writers and readers knew Lazar-us as a frequent contributor to periodicals such as Lippincott's, the Century, and the American Hebrew. She corresponded with writers and thinkers of the time, including Ivan Turgenev, William James, Robert Browning, and James Russell Lowell. When she died, the American Hebrew published the "Emma Lazarus Memorial Number." In it, John Hay, John Jay Whittier, and Cyrus Sulzberger, among others, praised Lazarus for her contributions to American literature as well as to "her own race and kindred." Lazar-us dedicated her life to her work. Yet she still had to contend with American and Jewish middle-class prescriptions for womanly behavior. These gender expectations included limitations on a woman artist's expression. In "Echoes" (probably written in 1880) Lazarus spoke selfconsciously about women as poets, describing the boundaries drawn around a woman poet who cannot share with men the common literary subjects of the "dangers, wounds, and triumphs" of war and must therefore transform her own "elf music" and "echoes" into song. Successful at that act of transformation, Lazarus found some space in the American literary world. More than any other Jewish woman of the nineteenth century, Lazarus identified herself and was recognized by readers and critics as an American writer. She was also an increasingly outspoken Jew, and she was a woman. Lazarus's writing benefited from the complexities of her identity. She would not have been as effective on behalf of Jews if she had not believed deeply in America's freedoms, and she could not have been as passionate a writer if she had not uncovered her own meaningful response to Judaism. SELECTED WORKS BY EMMA LAZARUS Admetus and Other Poems (1871); Alide: An Episode of Goethe's Life (1874); Emma Lazarus. Selections from Her Poetry and Prose. Edited by Morris Schappes (1944); Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine (188 1); Poems and Translations. Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen (1866); The Poems of Emma Lazarus. 2 vols. (188 8); Songs of a Semite: The Dance to Death and Other Poems (1882); The Spagnoletto (1876). From History.com http://www.history.com/topics/ellis-island Ellis Island opened in 1892 as a federal immigration station, a purpose it served for more than 60 years (it closed in 1954). Millions of newly arrived immigrants passed through the station during that time--in fact, it has been estimated that close to 40 percent of all current U.S. citizens can trace at least one of their ancestors to Ellis Island. America received large waves of European immigrants during the colonial era, the mid-19th century and from 1880 to 1920. Statue of Liberty Since 1886, the Statue of Liberty has stood tall in New York Harbor as an international symbol of freedom and democracy. Did You Know? It has been estimated that close to 40 percent of all current U.S. citizens can trace at least one of their ancestors to Ellis Island. Overview When Ellis Island opened, a great change was taking place in immigration to the United States. As arrivals from northern and western Europe--Germany, Ireland, Britain and the Scandinavian countries--slowed, more and more immigrants poured in from southern and eastern Europe. Among this new generation were Jews escaping from political and economic oppression in czarist Russia and eastern Europe (some 484,000 arrived in 1910 alone) and Italians escaping poverty in their country. There were also Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks and Greeks, along with non-Europeans from Syria, Turkey and Armenia. The reasons they left their homes in the Old World included war, drought, famine and religious persecution, and all had hopes for greater opportunity in the New World. After an arduous sea voyage, many passengers described their first glimpse of New Jersey, while third-class or steerage passengers lugged their possessions onto barges that would take them to Ellis Island. Immigrants were tagged with information from the ship's registry and passed through long lines for medical and legal inspections to determine if they were fit for entry into the United States. From 1900 to 1914--the peak years of Ellis Island's operation--some 5,000 to 10,000 people passed through the immigration station every day. Approximately 80 percent successfully passed through in a matter of hours, but others could be detained for days or weeks. Many immigrants remained in New York, while others traveled by barge to railroad stations in Hoboken or Jersey City, New Jersey, on their way to destinations across the country. Passage of the Immigrant Quota Act of 1921 and the National Origins Act of 1924, which limited the number and nationality of immigrants allowed into the United States, effectively ended the era of mass immigration into New York. From 1925 to its closing in 1954, only 2.3 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island--which was still more than half of all those entering the United States. Ellis Island opened to the public in 1976. Today, visitors can tour the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in the restored Main Arrivals Hall and trace their ancestors through millions of immigrant arrival records made available to the public in 2001. In this way, Ellis Island remains a central destination for millions of Americans seeking a glimpse into the history of their country, and in many cases, into their own family's story. Timeline 1630-1770 Ellis Island is no more than a lot of sand in the Hudson River, located just south of Manhattan. The Mohegan Indians who lived on the nearby shores call the island Kioshk, or Gull Island. In the 1630s, a Dutch man, Michael Paauw, acquires the island and renames it Oyster Island for the plentiful amounts of shellfish on its beaches. During the 1700s, it is known as Gibbet Island, for its gibbet, or gallows tree, used to hang men convicted of piracy. 1775-1865 Around the time of the Revolutionary War, the New York merchant Samuel Ellis purchases the island, and builds a tavern on it that caters to local fisherman. Ellis dies in 1794, and in 1808 New York State buys the island from his family for $10,000. The U.S. War Department pays the state for the right to use Ellis Island to build military fortifications and store ammunition, beginning during the War of 1812. Half a decade later, Ellis Island is used as a munitions arsenal for the Union army during the Civil War. Meanwhile, the first federal immigration law, the Naturalization Act, is passed in 1790; it allows all white males living in the U.S. for two years to become citizens. There is little regulation of immigration when the first great wave begins in 1814. Nearly 5 million people will arrive from northern and western Europe over the next 45 years. Castle Garden, one of the first state-run immigration depots, opens at the Battery in lower Manhattan in 1855. The potato blight that strikes Ireland and the ensuing famine (1846-50) leads to the immigration of over 1 million Irish alone in the next decade. Concurrently, large numbers of Germans flee political and economic unrest. Rapid settlement of the West begins with the passing of the Homestead Act in 1862. Attracted by the opportunity to own land, more Europeans begin to immigrate. 1865-1892 After the Civil War, Ellis Island stands vacant, until the government decides to replace the New York immigration station at Castle Garden, which closes in 1890. Control of immigration is turned over to the federal government, and $75,000 is appropriated for construction of the first federal immigration station on Ellis Island. Artesian wells are dug and the island's size is doubled to over six acres, with landfill created from incoming ships' ballast and the excavation of subway tunnels in New York. Beginning in 1875, the United States forbids prostitutes and criminals from entering the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act is passed in 1882. Restricted as well are "lunatics" and "idiots." 1892 The first Ellis Island Immigration Station officially opens on January 1, 1892, as three large ships wait to land. Seven hundred immigrants passed through Ellis Island that day, and nearly 450,000 followed over the course of that first year. Over the next five decades, more than 12 million people will pass through the island on their way into the United States. 1893-1899 On June 15, 1897, with 200 immigrants on the island, a fire breaks out in one of the towers in the main building and the roof collapses. Though no one is killed, all immigration records dating back to 1840 and the Castle Garden era are destroyed. The immigration station is relocated to the barge office in Manhattan's Battery Park. 1900-1902 On December 17, 1900, the New York Tribune offered a scathing account of conditions at the Battery station: "Grimy, gloomy...more suggestive of an enclosure for animals than a receiving station for prospective citizens of the United States." In response, the New York architectural firm Boring & Tilton reconstructs the immigrant station on Ellis Island at a total cost of $1.5 million. The new fireproof facility is officially opened in December, and 2,251 people pass through on opening day. To prevent a similar situation from occurring again, President Theodore Roosevelt appoints a new commissioner of immigration, William Williams, who cleans house on Ellis Island in 1902. To eliminate corruption, he awards contracts based on merit and announces contracts will be revoked if any dishonesty is suspected. He imposes penalties for any violation of this rule and posts "Kindness and Consideration" signs as reminders to workers. 1903-1910 To create additional space at Ellis Island, two new islands are created using landfill. Island Two houses the hospital administration and contagious diseases ward, while Island Three holds the psychiatric ward. By 1906, Ellis Island has grown to more than 27 acres, from an original size of only three acres. Anarchists are denied admittance into the U.S. as of 1903. On April 17, 1907, an all-time daily high of 11,747 immigrants received is reached; that year, Ellis Island experiences its highest number of immigrants received in a single year, with 1,004,756 arrivals. A federal law is passed excluding persons with physical and mental disabilities, as well as children arriving without adults. 1911-1919 World War I begins in 1914, and immigration to the U.S. slows dramatically. Ellis Island experiences a sharp decline in receiving immigrants: From 178,416 in 1915, the total drops to 28,867 in 1918. Anti-immigrant sentiment increases after the U.S. enters the war in 1917; approximately 1,800 German citizens are seized on ships in East Coast ports and interned at Ellis Island before being deported. Starting in 1917, Ellis Island operates as a hospital for the U.S. Army, a way station for Navy personnel and a detention center for enemy aliens. The literacy test is introduced at this time, and stays on the books until 1952. Those over the age of 16 who cannot read 30 to 40 test words in their native language are no longer admitted through Ellis Island. Nearly all Asian immigrants are banned. By 1918, the Army takes over most of Ellis Island and creates a makeshift way station to treat sick and wounded American servicemen. At war's end, a "Red Scare" grips America, in reaction to the triumph of the Russian Revolution. Ellis Island is used to intern immigrant radicals accused of subversive activity; many of them are deported. 1920-1935 President Warren G. Harding signs the Immigration Quota Act into law in 1921, after booming post-war immigration results in 590,971 people passing through Ellis Island. According to the new law, annual immigration from any country cannot exceed 3 percent of the total number of immigrants from a country living in the U.S. in 1910. The National Origins Act of 1924 goes even further, limiting total annual immigration to 165,000 and fixing quotas of immigrants from specific countries. The buildings on Ellis Island begin to fall into neglect and abandonment. America is experiencing the end of mass immigration. By 1932, the Great Depression has taken hold in the U.S., and for the first time more immigrants leave the country than arrive. 1950-1954 By 1949, the U.S. Coast Guard has taken over most of Ellis Island, using it for office and storage space. The passage of the Internal Security Act of 1950 excludes arriving immigrants with previous links to communist and fascist organizations. With this, Ellis Island experiences a brief resurgence in activity. Renovations and repairs are made in an effort to accommodate detainees, who sometimes number 1,500 at a time. The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952, combined with a liberalized detention policy, causes the number of detainees on the island to plummet to less than 30. All 33 structures on Ellis Island are officially closed in November 1954. In March 1955, the federal government declares the island surplus property; it is subsequently placed under the jurisdiction of the General Services Administration. 1965-1976 In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson issues Proclamation 3656, according to which Ellis Island falls under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Ellis Island opens to the public in 1976, featuring hour-long guided tours of the Main Arrivals Building. During this year, more than 50,000 people visit the island. Also in 1965, President Johnson signs a new immigration and naturalization bill, the Hart-Cellar Act, which abolishes the earlier quota system based on national origin and establishes the foundations for modern U.S. immigration law. The act allows more individuals from third-world countries to enter the U.S. (including Asians, who have in the past been barred from entry) and establishes a separate quota for refugees. 1982-1990 In 1982, at the request of President Ronald Reagan, Lee Iacocca of the Chrysler Corporation heads the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation to raise funds from private investors for the restoration and preservation of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty. By 1984, when the restoration begins, the annual number of visitors to Ellis Island has reached 70,000. The $156 million dollar restoration of Ellis Island's Main Arrivals Building is completed and re-opened to the public in 1990, two years ahead of schedule. The Main Building houses the new Ellis Island Immigration Museum, in which many of the rooms have been restored to the way they appeared during the island's peak years. Since 1990, some 30 million visitors have visited Ellis Island to trace the steps of their ancestors. Meanwhile, immigration into the U.S. continues, mostly by land routes through Canada and Mexico. Illegal immigration becomes a constant source of political debate throughout the 1980s and 1990s. More than 3 million aliens receive amnesty through the Immigration Reform Act in 1986, but an economic recession in the early 1990s is accompanied by a resurgence of anti-immigrant feeling. 1998 In 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that New Jersey has authority over the south side of Ellis Island, or the section composed of the landfill added after 1834. New York retains authority over the island's original 3.5 acres, which includes the bulk of the Main Arrivals Building. The policies put into effect by the Immigration Act of 1965 have greatly changed the face of the American population by the end of the 20th century. Whereas in the 1950s, more than half of all immigrants were Europeans and just 6 percent were Asians, by the 1990s only 16 percent are Europeans and 31 percent are Asians, and the percentages of Latino and African immigrants also jump significantly. Between 1965 and 2000, the highest number of immigrants (4.3 million) to the U.S. comes from Mexico; 1.4 million are from the Philippines. Korea, the Dominican Republic, India, Cuba and Vietnam are also leading sources of immigrants, each sending between 700,000 and 800,000 over this period. 2001 The American Family Immigration History Center opens on Ellis Island in 2001. The center allows visitors to search through millions of immigrant arrival records for information on individual people who passed through Ellis Island on their way into the United States. The records include the original manifests, given to passengers onboard ships and showing names and other information, as well as information about the history and background of the ships that arrived in New York Harbor bearing hopeful immigrants to the New World. Debates continue over how America should confront the effects of soaring immigration rates throughout the 1990s. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 creates the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which takes over many immigration service and enforcement functions formerly performed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). 2008 Plans are announced for an expansion of the Ellis Island Immigration Museum called "The Peopling of America," which is scheduled to be completed in 2011. The museum's exploration of the Ellis Island era (1892-1954) will be expanded to include the entire American immigration experience up to the present day. Eighty-five percent white in 1965, the nation is currently one-third minority and on track for a non-white majority by 2 Trivia The First Arrival On January 1, 1892--her 15th birthday--Annie Moore from County Cork, Ireland, became the first person admitted to the new immigration station on Ellis Island. On that opening day, she received a greeting from officials and a $10.00 gold piece. Annie traveled to New York with her two younger brothers on steerage aboard the S.S. Nevada, which left Queenstown (now Cobh) on December 20, 1891 and arrived in New York on the evening of December 31. After being processed, the children were reunited with their parents, who were already living in New York. Beware the Buttonhook Men Doctors checked those passing through Ellis Island for more than 60 diseases and disabilities that might disqualify them from entry into the United States. Those suspected of being afflicted with a having a disease or disability were marked with chalk and detained for closer examination. All immigrants were checked closely for trachoma, a contagious eye condition that caused more detainments and deportations than any other ailment. To check for trachoma, the examiner used a buttonhook to turn each immigrant's eyelids inside out, a procedure remembered by many Ellis Island arrivals as particularly painful and terrifying. Dining at Ellis Island Food was plentiful at Ellis Island, despite various opinions as to its quality. A typical meal served in the dining hall might include beef stew, potatoes, bread and herring (a very cheap fish); or baked beans and stewed prunes. Immigrants were introduced to new foods, such as bananas, sandwiches and ice cream, as well as unfamiliar preparations. To meet the special dietary requirements of Jewish immigrants, a kosher kitchen was built in 1911. In addition to the free meals served, independent concessions sold packaged food that immigrants often bought to eat while they waited or take with them when they left the island. Famous Names Many famous figures passed through Ellis Island, many leaving their original names behind on their entry into the U.S. Israel Beilin--better known as composer Irving Berlin--arrived in 1893; Angelo Siciliano, who arrived in 1903, later achieved fame as the bodybuilder Charles Atlas. Lily Chaucoin arrived from France to New York in 1911 and found Hollywood stardom as Claudette Colbert. Some were already famous when they arrived, such as Carl Jung or Sigmund Freud (both 1909), while some, like Charles Chaplin (1912) would make their name in the New World. A Future Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, the future mayor of New York City, worked as an interpreter for the Immigration Service at Ellis Island from 1907 to 1910, while he was completing law school at New York University. Born in New York in 1882 to immigrants of Italian and Jewish ancestry, La Guardia lived for a time in Hungary and worked at the American consulates in Budapest and other cities. From his experience at Ellis Island, La Guardia came to believe that many of the deportations for so-called mental illness were unjustified, often due to communication problems or to the ignorance of doctors doing the inspections. "I'm Coming to New Jersey" After a lengthy court battle, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1998 that the state of New Jersey, not New York, had authority over the majority of the 27.5 acres that make up Ellis Island. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the island's southern portion, or the section composed of landfill added after 1834, is part of Jersey City. New York retained ownership over the original three acres, including the Main Arrivals Hall and the Ellis Island Immigration Museum. One of the most vocal New York boosters, then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, famously remarked of the court's decision: "They're still not going to convince me that my grandfather, when he was sitting in Italy, thinking of coming to the United States, and on the shores getting ready to get on that ship in Genoa, was saying to himself, 'I'm coming to New Jersey.' He knew where he was coming to. He was coming to the streets of New York. Gathering and Interactions of Peoples, Cultures, and Ideas A Brief Timeline of U.S. Policy on Immigration and Naturalization 1790 Congress adopts uniform rules so that any free white person could apply for citizenship after two years of residency. 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts required 14 years of residency before citizenship and provided for the deportation of "dangerous" aliens. Changed to five-year residency in 1800. 1819 First significant federal legislation on immigration. Includes reporting of immigration and rules for passengers from US ports bound for Europe 1846 Irish of all classes emigrate to the United States as a result of the potato famine. 1857 Dred Scott decision declared free Africans non-citizens. 1864 Contract Labor Law allowed recruiting of foreign labor. 1868 African Americans gained citizenship with 14th Amendment. 1875 Henderson v. Mayor of New York decision declared all state laws governing immigration unconstitutional; Congress must regulate "foreign commerce." Charity workers, burdened with helping immigrants, petition Congress to exercise authority and regulate immigration. Congress prohibits convicts and prostitutes from entering the country. 1880 The U.S. population is 50,155,783. More than 5.2 million immigrants enter the country between 1880 and 1890. 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. First federal immigration law suspended Chinese immigration for 10 years and barred Chinese in U.S. from citizenship. Also barred convicts, lunatics, and others unable to care for themselves from entering. Head tax placed on immigrants. 1885 Contract Labor Law. Unlawful to import unskilled aliens from overseas as laborers. Regulations did not pertain to those crossing land borders. 1888 For the first time since 1798, provisions are adopted for expulsion of aliens. 1889 Jane Addams founds Hull-House on Chicago's Near West Side. 1890 Foreign-born in US were 15% of population (14% in Vermont); more arriving from southern and eastern Europe ("new immigrants") than northern and western ("old immigrants"). Jacob Riis publishes "How the Other Half Lives." 1891 Bureau of Immigration established under the Treasury Department. More classes of aliens restricted including those who were monetarily assisted by others for their passage. Steamship companies were ordered to return ineligible immigrants to countries of origin. 1892 Ellis Island opened to screen immigrants entering on east coast. (Angel Island screened those on west coast.) Ellis Island officials reported that women traveling alone must be met by a man, or they were immediately deported. 1902 Chinese Exclusion Act renewed indefinitely. 1903 Anarchists, epileptics, polygamists, and beggars ruled inadmissible. 1905 Construction of Angel Island Immigration Station began in the area known as China Cove. Surrounded by public controversy from its inception, the station was finally put into operation in 1910. Although it was billed as the "Ellis Island of the West", within the Immigration Service it was known as "The Guardian of the Western Gate" and was designed control the flow of Chinese into the country, who were officially not welcome with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. 1906 Procedural safeguards enacted for naturalization. Knowledge of English becomes a basic requirement. 1907 Head tax is raised. People with physical or mental defects, tuberculosis, and children unaccompanied by a parent are added to the exclusion list. Japan agreed to limit emigrants to US in return for elimination of segregating Japanese students in San Francisco schools. 1910 Dillingham Report from Congress assumed inferiority of "new immigrants" from southern and eastern Europe and suggested a literacy test to restrict their entry. (William P. Dillingham was a Senator from Vermont.) 1917 Immigration Act provided for literacy tests for those over 16 and established an "Asiatic Barred Zone," which barred all immigrants from Asia. 1921 Quota Act of 1921 limited immigrants to 3% of each nationality present in the US in 1910. This cut southern and eastern European immigrants to less than 1/4 of those in US before WW I. Asians still barred; no limits on western hemisphere. Non-quota category established: wives, children of citizens, learned professionals, and domestic servants not counted in quotas. 1922 Japanese made ineligible for citizenship. 1924 Quotas changed to 2% of each nationality based on numbers in US in 1890. Based on surnames (many anglicized at Ellis Island) and not the census figures, 82% of all immigrants allowed in the country came from western and northern Europe, 16% from southern and eastern Europe, 2% from the rest of the world. As no distinctions were made between refugees and immigrants, this limited Jewish emigres during 1930s and 40s. Despite protests from many native people, Native Americans made citizens of the United States. Border Patrol established. 1929 The annual quotas of the 1924 Act are made permanent. 1940 Provided for finger printing and registering of all aliens. 1943 In the name of unity among the Allies, the Chinese Exclusion Laws were repealed, and China's quota was set at a token 105 immigrants annually. Basis of the Bracero Program established with importation of agricultural workers from North, South, and Central America. 1946 Procedures adopted to facilitate immigration of foreign-born wives, finace(e)s, husbands, and children of US armed forces personnel. 1948 Displaced Persons Act allowed 205,000 refugees over two years; gave priority to Baltic States refugees; admitted as quota immigrants. Technical provisions discriminated against Catholics and Jews; those were dropped in 1953, and 205,000 refugees were accepted as non-quota immigrants. 1950 The grounds for exclusion and deportation are expanded. All aliens required to report their addresses annually. 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act eliminated race as a bar to immigration or citizenship. Japan's quota was set at 185 annually. China's stayed at 105; other Asian countries were given 100 a piece. Northern and western Europe's quota was placed at 85% of all immigrants. Tighter restrictions were placed on immigrants coming from British colonies in order to stem the tide of black West Indians entering under Britain's generous quota. Non-quota class enlarged to include husbands of American women. 1953 The 1948 refugee law expanded to admit 200,000 above the existing limit 1965 Hart-Celler Act abolished national origins quotas, establishing separate ceilings for the eastern (170,000) and western (120,000) hemispheres (combined in 1978). Categories of preference based on family ties, critical skills, artistic excellence, and refugee status. 1978 Separate ceilings for Western and Eastern hemispheric immigration combined into a worldwide limit of 290,000. 1980 The Refugee Act removes refugees as a preference category; reduces worldwide ceiling for immigration to 270,000. 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act provided for amnesty for many illegal aliens and sanctions for employers hiring illegals. 1989 A bill gives permanent status to non-immigrant registered nurses who have lived in US for at least three years and met established certification standards. 1990 Immigration Act of 1990 limited unskilled workers to 10,000/year; skilled labor requirements and immediate family reunification major goals. Continued to promote nuclear family model. Foreign-born in US was 7%. 2001 USA Patriot Act amended the Immigration and Nationality Act to broaden the scope of aliens ineligible for admission or deportable due to terrorist activities to include an alien who: (1) is a representative of a political, social, or similar group whose political endorsement of terrorist acts undermines U.S. antiterrorist efforts; (2) has used a position of prominence to endorse terrorist activity, or to persuade others to support such activity in a way that undermines U.S. antiterrorist efforts (or the child or spouse of such an alien under specified circumstances); or (3) has been associated with a terrorist organization and intends to engage in threatening activities while in the United States. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/immigration/timeline.html HARVARD UNIVERSITY Key Dates and Landmarks in United States Immigration History 1789 The Constitution of the United States of America takes effect, succeeding the Articles of Confederation that had governed the union of states since the conclusion of the Revolutionary War (March 4, 1789). 1790 The Naturalization Act of 1790 establishes a uniform rule of naturalization and a two-year residency requirement for aliens who are "free white persons" of "good moral character" (March 26, 1790). 1798 Considered one of the Alien and Sedition Acts, the Naturalization Act of 1798 permits Federalist President John Adams to deport foreigners deemed to be dangerous and increases the residency requirements to 14 years to prevent immigrants, who predominantly voted for the Republican Party, from becoming citizens (June 25, 1798). 1802 The Jefferson Administration revises the Naturalization Act of 1798 by reducing the residency requirement from 14 to five years. 1808 Importation of slaves into the United States is officially banned, though it continues illegally long after the ban. 1819 Congress passes an act requiring shipmasters to deliver a manifest enumerating all aliens transported for immigration. The Secretary of State is required to report annually to Congress the number of immigrants admitted. 1821–1830 143,439 immigrants arrive 1831–1840 599,125 immigrants arrive 1840s Crop failures in Germany, social turbulence triggered by the rapid industrialization of European society, political unrest in Europe, and the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1851) lead to a new period of mass immigration to the United States. 1841–1850 1,713,251 immigrants arrive 1848 The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ends the Mexican-American War and extends citizenship to the approximately 80,000 Mexicans living in Texas, California, and the American Southwest. 1848 Gold is discovered in the American River, near Sacramento, California. 1849 The California gold rush spurs immigration from China and extensive internal migration. 1850 For the first time, the United States Census surveys the "nativity" of citizens (born inside or outside the US). 1851–1860 2,598,214 immigrants arrive 1854 The Know-Nothings, a nativist political party seeking to increase restrictions on immigration, win significant victories in Congress, a sign of popular dissatisfaction with growing immigration from Catholic Ireland. Protestant Americans feared that growing Catholic immigration would place American society under control of the Pope. 1855 Castle Garden is established as New York's principal point of entry. 1861–1870 2,314,825 immigrants arrive 1861 Outbreak of the American Civil War (April 12, 1861). 1862 The Homestead Act provides free plots of up to 160 acres of western land to settlers who agree to develop and live on it for at least five years, thereby spurring an influx of immigrants from overpopulated countries in Europe seeking land of their own. 1862 The "Anti-Coolie" Act discourages Chinese immigration to California and institutes special taxes on employers who hire Chinese workers. 1863 Riots against the draft in New York City involve many immigrants opposed to compulsory military service (July 13–16, 1863). 1863 The Central Pacific hires Chinese laborers and the Union Pacific hires Irish laborers to construct the first transcontinental railroad, which would stretch from San Francisco to Omaha, allowing continuous travel by rail from coast to coast. 1869 The First Transcontinental Railroad is completed when the Central Pacific and Union Pacific lines meet at Promontory Summit, Utah (May 10, 1869). 1870 The Naturalization Act of 1870 expands citizenship to both whites and African-Americans, though Asians are still excluded. 1870 The Fifteenth Amendment is ratified, granting voting rights to citizens, regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." 1870 Jacob Riis, who later pioneered photojournalism and authored How the Other Half Lives, emigrates from Denmark to the United States. 1871–1880 2,812,191 immigrants arrive 1881–1890 5,246,613 immigrants arrive 1881–1885 1 million Germans arrive in the peak of German immigration 1881–1920 2 million Eastern European Jews immigrate to the United States 1882 The Chinese Exclusion Act restricts all Chinese immigration to the United States for a period of ten years. 1882 The Immigration Act of 1882 levies a tax of 50 cents on all immigrants landing at US ports and makes several categories of immigrants ineligible for citizenship, including "lunatics" and people likely to become public charges. 1885 The Alien Contract Labor Law prohibits any company or individual from bringing foreigners into the United States under contract to perform labor. The only exceptions are those immigrants brought to perform domestic service and skilled workmen needed to help establish a new trade or industry in the US. 1886 The Statue of Liberty is dedicated in New York Harbor. 1886 Emma Goldman, Lithuanian-born feminist, immigrates to the United States, where over the next 30 years she will become a prominent American anarchist. During the First World War, in 1917, she is deported to Russia for conspiring to obstruct the draft. 1889 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr found Hull-House in Chicago. 1890 The demographic trends in immigration to the United States shift as immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe substantially increases, while the relative proportion of immigration from Northern and Western Europe begins to decrease. 1891–1900 3,687,564 immigrants arrive. 1891 Congress makes "persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease," those convicted of a "misdemeanor involving moral turpitude," and polygamists ineligible for immigration. Congress also establishes the Office of the Superintendent of Immigration within the Treasury Department. 1892 The Geary Act extends the Chinese Exclusion Act for ten more years, and adds the requirement that all Chinese residents carry permits, as well as excluding them from serving as witnesses in court and from bail in habeus corpus proceedings. 1892 Ellis Island, the location at which more than 16 million immigrants would be processed, opens in New York City. 1901–1910 8,795,386 immigrants arrive 1901 After President William McKinley is shot by a Polish anarchist (September 6, 1901) and dies a week later (September 14, 1901), Congress enacts the Anarchist Exclusion Act, which prohibits the entry into the US of people judged to be anarchists and political extremists. 1902 The Chinese Exclusion Act is again renewed, with no ending date. 1906 The Naturalization Act of 1906 standardizes naturalization procedures, makes some knowledge of the English language a requirement for citizenship, and establishes the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization in the Commerce Department to oversee national immigration policy. 1907 The Expatriation Act declares that an American woman who marries a foreign national loses her citizenship. 1907 Under an informal "Gentlemen's Agreement," the United States agrees not to restrict Japanese immigration in exchange for Japan's promise to voluntarily restrict Japanese emigration to the United States by not issuing passports to Japanese laborers. In return, the US promises to crack down on discrimination against Japanese-Americans, most of whom live in California. 1907 The Dillingham Commission is established by Congress to investigate the effects of immigration on the United States. 1911–1920 2 million Italians arrive in the peak of Italian immigration 1911–1920 5,735,811 immigrants arrive 1911 The Dillingham Commission, established in 1907, publishes a 42-volume report warning that the "new" immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe threatens to subvert American society. The Dillingham Commission's recommendations lay the foundation for the Quota Acts of the 1920s. 1913 California's Alien Land Law prohibits "aliens ineligible for citizenship" (Chinese and Japanese) from owning property in the state, providing a model for similar anti-Asian laws in other states. 1917 Congress enacts a literacy requirement for immigrants by overriding President Woodrow Wilson's veto. The law requires immigrants to be able to read 40 words in some language and bans immigration from Asia, except for Japan and the Philippines. 1917 The US enters the First World War. 1917 The Immigration Act of 1917 restricts immigration from Asia by creating an "Asiatic Barred Zone." 1917 The Jones-Shafroth Act grants US citizenship to Puerto Ricans, provided that they can be recruited by the US military. 1919 The First Red Scare leads to an outbreak of fear and violence against people deemed to be political radicals and foreigners considered to be susceptible to communist propaganda and more likely to be involved in the Bolshevik Revolution. 1921–1930 4,107,209 immigrants arrive. 1921 The Emergency Quota Act restricts immigration from a given country to 3% of the number of people from that country living in the US in 1910. 1922 The Cable Act partially repeals the Expatriation Act, but declares that an American woman who marries an Asian still loses her citizenship. 1923 In the landmark case of United States v. Bhaghat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court rules that Indians from the Asian subcontinent cannot become US citizens. 1924 The Immigration Act of 1924 limits annual European immigration to 2% of the number of people from that country living in the United States in 1890. The Act greatly reduces immigration from Southern and Eastern European nationalities that had only small populations in the US in 1890. 1924 The Oriental Exclusion Act prohibits most immigration from Asia, including foreign-born wives and the children of American citizens of Chinese ancestry. 1924 The Border Patrol is created to combat smuggling and illegal immigration. 1929 The National Origins Formula institutes a quota that caps national immigration at 150,000 and completely bars Asian immigration, though immigration from the Western Hemisphere is still permitted. 1931–1940 532,431 immigrants arrive. 1933 To escape persecution by the Nazis, Albert Einstein, the greatest theoretical physicist of the century, immigrates to the United States from Germany. 1934 The Tydings-McDuffe Act grants the Philippines independence from the United States on July 4, 1946, but strips Filipinos of US citizenship and severely restricts Filipino immigration to the United States. 1940 The Alien Registration Act requires the registration and fingerprinting of all aliens in the United States over the age of 14. http://www.maggieblanck.com/Immigration.html - Ellis island images http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/2011/06/immigration.html immigration images Eyewitness accounts of Immigration From: http://www.nps.gov/elis/forteachers/primary-sources-for-your-classroom.htm National Park, Ellis Island Elda Remembers The Eye Exam (Transcript) Interviewee: Elda Del Bino Willitts Date of Birth: April 28, 1911 Date of Interview: November 9, 1990 Interviewer: Paul E. Sigrist, Jr. Immigrated from Lucca, Italy at Age 5 in 1916 Ellis Island Collection: EI-8 When I got on the boat, I was only five and this little, this gentleman who had been back and forth several times, and well my mother took a liking to him because he was so knowledgeable about it. He spoke Italian. And so he took me on a walk one day and he said, "You know what? When you get over to Ellis Island they're going to be examining your eyes with a hook," and he says, "Don't let them do it because you know what? They did it to me one eye fell in my pocket. (Paul laughs) So you can imagine how I entered this...So we get over there and everybody has to pass and I'm on the floor screaming. I passed without a physical. I passed the eye test because the other seven passed. Gertrude Remembers Changing Her Name (Transcript) Interviewee: Gertrude (Gudrun) Hildebrandt Moller Date of Birth: June 15, 1920 Date of Interview: October 5, 1992 Interviewer: Janet Levine, Ph.D Immigrated from Germany in 1929 at Age 9 Ellis Island Collection: EI-222 Moller (Name Change in School): I was born Gudrun Hildebrandt and married Moller, Mr. Moller, who was from Denmark. He immigrated here many years later and we met in New York. However when I started school in Chicago, where I grew up, needless to say, first of all, I couldn't speak a word of English, and I was the only child in the school that couldn't speak English. And (she laughs) it wasn't too happy the first couple of years but my mama said "Take heart because some day you're going to be able to speak two languages and all the ones that were teasing you will speak only one". And it was true. She was always right. So, my teacher suggested, since none of the children could pronounce Gudrun, which is an old Germanic-Scandinavian name, and a very beautiful name (I hear), she gave me a list of girls' names to choose from. So that all the kids could converse, you know, know what to call me. So I picked the name starting with a g, as with my name, and it was Gertrude. I'm not very happy with it, but it has stuck with me all of these years. Interviewee: Charles W. Beller (Kalman Bilchick) Date of Birth: November 4, 1903 Date of Interview: August 29, 1991 Interviewer: Janet Levine, Ph.D. Immigrated from Russia at age 6 in 1910 Ellis Island Collection: EI-82 Levine: Did your mother and father have the attitude that they wanted their children to become Americanized and they wanted them to hold on to the traditions of Jews in Russia? Beller (Maintaining Cultural Identity): My father would want us to go to synagogue on the high holy days; and I always went with him. The other boys, they strayed away from the religious part of it. But I always went with him on every high holiday and the like. I went to Hebrew school. I had the rabbi come to the house for awhile. Then I went to the Rabbi's place in order to learn until I was thirteen years old. And after that I didn't care about that. I wanted to be Americanized. I want to be an American, and I want to accept my opportunities and take the, make the most of them. Take advantage of everything that I could learn. And I did just that. Emma and William Remember Packing (Transcript) Interviewee: Emma and William Greiner Date of Birth: December 30, 1913 and July 18, 1912 Date of Interview: March 3, 1991 Interviewer: Paul E. Sigrist, Jr. Immigrated from Italy (on German and French Quotas) at Age 11 and 12 in 1925 Ellis Island Collection: EI-28 Greiner (What He Packed): EMMA: Yes, yes. It was very disrupting, you know, to pack and break up your home. Oh, we took, of course, our clothing and some pieces of like china that were very, very special. And maybe a blanket or two also that were real good wool, that we felt maybe we may not be able to get here in the United States. WILLIAM: Of course, there was pressure to leave things there but they accommodated us kids. And I brought a lot of things that (he laughs) I now wonder why I was so attached, for instance, to greeting cards. They were very, very romantic in those days and they were through the years birthdays and so on. And a few toys. My tin soldiers. I don't remember whether I brought anything about my small railroad, um. WILLIAM: Oh, yes, yes. And then I had, uh, what we called a "Magic Lantern." It was a... Projector. Very, very primitive, (he laughs) compared to today's. EMMA: And I was hoping he wouldn't bring those soldiers because when we played together at home, you see I was German and he was French, you know, and he would always decimate all my soldiers, kill them all off, so we had quite a different set in our lives...(she laughs) William Remembers the Storm (Transcript) Interviewee: William Greiner Date of Birth: July 18, 1912 Date of Interview: March 3, 1991 Interviewer: Paul E. Sigrist, Jr. Immigrated from Italy (on French Quota) at Age 12 in 1925 Ellis Island Collection: EI-28 Greiner: It's hard for people to understand today what it was like to be on a boat then in a storm like that. Tremendous noise. It sounded as if the boat was heading for some rocks. The great waves would smash, the noise tremendous, and I thought we would flounder at any moment. They posted Morse Code, messages received from other ships in the ocean, sending "S.O.S. We are floundering!" and so on, "Help!" and the captain let us know that he couldn't get out of the way. They were hard pressed, too. So they wanted to get to New York as soon as possible… all the other people were so sick. But I get over very quickly any sickness. I would go up on the captain's deck and I enjoyed this wild sight, and especially looking at the prow of the ship going way, way down under the sea and then lifting up. And the waves coming, rushing right up to the captain's...to live...that's a terrifying scene but, as a boy, I enjoyed it. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410654_NABEPresentation.pdf Population graphs