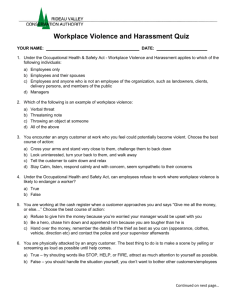

Appendix Sources used in the study

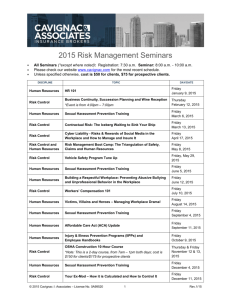

advertisement