Claire Mummé

advertisement

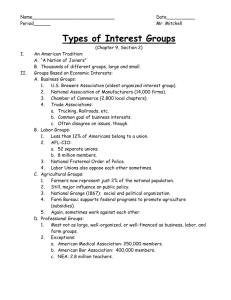

+ Where Are We Now? Unions’ Post-Weber Representational Responsibilities For Human Rights in the Workplace Claire Mummé, University of Windsor Faculty of Law 1 + 2 Plan of Presentation Introduction This presentation suggests a research agenda for assessing the extent to which expanded jurisdiction over human rights issues since Weber has affected the way unions’ represent their members. Has the DFR case law changed since/in function of Weber? Claims against unions at the HRTs. Res judicata/s.45.1 as between DFR and human rights claims. Some empirical questions in need of further research. Concluding thoughts. + 3 Introduction In the early years, analysis of the Weber decision invariably raised questions about the practical strain exclusive arbitral jurisdiction would place on unions and labour arbitrators. Amongst concerns raised was the degree to which Weber expanded unions’ representational responsibilities for members’ human rights issues and discrimination in the workplace. + 4 Introduction Bernie Adell voiced this concern forcefully: “The increasingly frequent links between anti-discrimination rights, which are vested in individuals, and the collective agreement administration process, which privileges collective rights, threaten to put very heavy pressure on the DFR both in theory and in practice. Those pressures are further aggravated by the various lines of jurisprudence stemming from Weber v. Ontario Hydro. [T]hat jurisprudence is giving unions and the grievance arbitration process an as yet ill-defined range of new responsibilities for enforcing employee rights (and duties) previously enforced in other forums […].” Bernard Adell, “Jurisdictional Overlap Between Arbitration and Other Forums”, (2000) 8 Canadian Lab. & Emp. L.J. 179 at p.224 + 5 Introduction There is an anecdotal sense that Weber has had a significant impact on unions’ human rights responsibilities, but it is difficult to assess the nature and extent of that impact. There are two types of questions provoked by this topic. 1. Whether unions now hold greater representational responsibilities regarding their members’ human rights issues. Analysis of DFR and human rights claims against unions for discrimination. My focus here is on unions’ representational obligations rather than issues surrounding discriminatory terms of CBAs. 2. How are unions navigating their options as regards proceeding to arbitration or to the human rights tribunals. Further empirical research suggested to complement the findings other presenters, notably those of Sara Slinn and Brian Etherington. *Not addressing the negotiation of CBA terms with discriminatory impact + 6 Has the DFR Standard Changed? One of the big questions raised after Weber was whether the union veto over access to arbitration would heighten the DFR standard when members’ asserted a human rights issue. This does not appear to have occurred. For the most part, the current DFR standard appears to be effectively the same as in the pre-Weber era. + 7 The Pre-Weber DFR Standard Canadian Merchant Service Guild v. Gagnon, [1984] 1 S.C.R. 509 The exclusive power conferred on a union to act as spokesman for the employees in a bargaining unit entails a corresponding obligation on the union to fairly represent all employees comprised in the unit. When, as is true here, and is generally the case, the right to take a grievance to arbitration is reserved to the union, the employee does not have an absolute right to arbitration and the union enjoys considerable discretion. The discretion must be exercised in good faith, objectively and honestly, after a thorough study of the grievance and the case, taking into account the significance of the grievance and of the consequence for the employee on the one hand and the legitimate interest of the union on the other. The union's decision must not be arbitrary, capricious, discriminatory or wrongful. The representation by the union must be fair, genuine and not merely apparent, undertaken with integrity and competence, without serious or major negligence, and without hostility towards the employee. + 8 The Post-Weber DFR Standard Noël v. Société d’énergie de la Baie James, [2001] 2 S.C.R. 207, 2001 SCC 39, paras 49-53 First, s. 47.2 [of the QC Labour Code] prohibits acting in bad faith, which presumes intent to harm or malicious, fraudulent, spiteful or hostile conduct In practice, this element alone would be difficult to prove. The law also prohibits discriminatory conduct. This includes any attempt to put an individual or group at a disadvantage where this is not justified by the labour relations situation in the company. The concepts of arbitrary conduct and serious negligence, which are closely related, refer to the quality of the union representation. The inclusion of arbitrary conduct means that even where there is no intent to harm, the union may not process an employee’s complaint in a superficial or careless manner. […]. The fourth element in [the Quebec Labour Code] is serious negligence. A gross error in processing a grievance may be regarded as serious negligence despite the absence of intent to harm. However, mere incompetence in processing the case will not breach the duty of representation, since s. 47.2 does not impose perfection as the standard in defining the duty of diligence assumed by the union + 9 The Post-Weber DFR Standard In 2000-2001 Bernie Adell in the Labour Arb YB suggested that there appeared to be an emerging duty to be proactive in assisting employees secure accommodation. “[T]he past few years have seen a subtle but significant rise in the standard of representation that unions must meet in order to comply with the DFR, especially in discrimination grievances.” - Bernard Adell, “The Union’s Duty of Fair Representation in Discrimination Cases: The New Obligation to Arb YB 263 at p.266 be Proactive”, (2001-2002) 2 Labour He also noted, however, that this duty to be proactive was not yet fully established/accepted. In Bingley v. Teamsters, Local 91[2004] C.I.R.B. No. 29, the CIRB built on Adell’s suggestion, elaborating a duty to be proactive when dealing with disability and accommodation. + 10 The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Bingley v. Teamsters, Local 91[2004] C.I.R.B. No. 291. After discussing the two Renaud scenarios for union liability for discrimination, the Board held that Renaud suggested that “the union’s responsibility may also be engaged when it does not address the discrimination even though it did not cause or take part in the discriminatory work policy.” para 59 After discussing Parry Sound, the Board stated that “[…] a union may be held responsible of the discriminatory effects of an employment policy decision by not seeking to put an end to the discrimination.” para 61 + 11 The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Bingley cont’d The Board then turned to the DFR “Due to the sensitive and important issues associated with the accommodation of disabled workers in the workplace, labour boards also look to see whether unions have given disabled employees’ grievances greater scrutiny. The cases generally concur that the usual procedure applied to other members of the bargaining unit may be insufficient in representing a grievor with a disability, mainly because the member’s situation will require a different approach.” para 64. “ Overall […] when a member has some kind of disability, the union must not only handle the grievance in an “ordinary” manner, but has to put some extra effort into the case. Thus, the union cannot handle the case like any other grievance; it must be proactive and more attentive in its approach.” + 12 The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Bingley supra cont’d 83 ”The case law leaves little doubt that to discharge their duty of fair representation, unions are required to take an extra measure of care and show an extra measure of assertiveness when representing a member who is alleging a violation of statutory anti-discrimination rights.” + 13 The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Schwartzman v. M.G.E.U., [2010] M.L.B.D. No. 49 Board approved of Bingley and discussed unions’ obligations in dealing with issues of disability and accommodation. However, the Board ultimately concluded that the union met their obligations on the facts. Drawing from Gendron, the Board noted that accommodation issues are critical interests deserving particular attention by unions. “In the circumstance of a disabled employee alleging a violation of statutory anti-discrimination rights, the employment interests are serious and any associated grievance may have enormous consequences for the employee.” + 14 The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Schwartzman cont’d “ Unions must be particularly alert and sensitive to an employee’s disability and the employment interests at stake in cases concerning the application of human rights principles. + The Post-Weber DFR Standard: the Bingley cases Ultimately, however, I’ve located only one case applying Bingley to find a violation of the DFR. - Pepper v Teamsters Local 879, 2009 CIRB 453. The idea that a human rights issue is a critical interest remains largely undeveloped. The cases which suggest a higher standard of representation all concern disability. I have not seen any discussion of a higher standard in regards to any other prohibited ground of discrimination. Generally, the DFR case law does not seem to have changed significantly in function Weber as regards members’ human rights issues. 15 + 16 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals With the growing recognition of concurrent jurisdiction over human rights claims, there appears to be an increasing number of claims for discrimination made against unions before human rights tribunals. In Ontario this seems particularly so since the implementation of the direct access model (see empirical questions slides 25-26) The labour boards and the human rights tribunals recognize concurrent jurisdiction between them over claims that a union acted in a discriminatory fashion against a member. + 17 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals In Gungor v. Canadian Auto Workers Local 88, 2011 HRTO 1760, the HRTO discussed the ways in which a union could violate the Human Rights Code. The Tribunal noted that a union could “discriminate in employment” (s.5 of the OHRC) only in the two situations noted by the SCC in Central Okanagan School District No. 23 v. Renaud, [1992] 2 S.C.R. 970 ("Renaud") 1 – Where the union participates in the formulation of the work rule that has the discriminatory effect on the complainant – codiscrimination; 2 - Where the union impedes the reasonable efforts of an employer to accommodate (contributory discrimination – E. Shilton) + 18 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals The Tribunal in Gungor supra went on to hold that where the impugned union conduct was inaction, the claim would fall under s.6, membership. Relying on Traversy v. Mississauga Professional Firefighters Association, Local 1212, 2009 HRTO 996 , the Tribunal was clear however that a union’s failure to act does not in of itself constitute discrimination. The Tribunal cited the following passage from Traversy supra: “[A] claim that the union violates the Code must be based on an assertion of differential treatment, and not simply a failure to act. The failure or refusal to take forward a human rights issue such as accommodation of a disability in the workplace is not, in and of itself, a breach of the Code. There must be a claim, and a factual foundation for the claim, that the failure to act was based on discriminatory factors.” Traversy supra at para 33. + 19 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals Moreover, the Tribunal in Gungor noted, its jurisdiction regarding union inaction is limited. “This kind of conduct [union inaction] may or may not provide a basis for a duty of fair representation complaint against the union under s. 74 of the Labour Relations Act. But it is not this Tribunal's jurisdiction to determine whether a union fairly or adequately represented a member in the absence of evidence that its conduct was based on a discriminatory factor. That is the role and jurisdiction of the Ontario Labour Relations Board.” Gungor, supra, para 47. + 20 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals Gungor Cont’d The Tribunal was urged to adopt the holding in Bingley, although a DFR case. The Tribunal declined to do so. The Vice-Chair argued that the LRBs and HRTs have different roles as regards discrimination. The LRBs, he argued, have “direct and immediate jurisdiction” to assess and rule on the adequacy of a union’s representation, including human rights issues. By contrast, the HRTs are capable of dealing with the underlying human rights issue that is the subject of the applicant’s concerns about any lack of union representation. Moreover, the Vice-Chair argued, the CIRB got Renaud wrong in Bingley. + 21 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals But, there’s something slightly strange in the HRTO’s jurisprudence regarding discrimination in union representation. + 22 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals The HRTO usually analyzes discrimination in union membership based on Traversy, supra. The following passage is cited in almost all HRTO claims under s.6 against unions. “A claim that the union violates the Code must be based on an assertion of differential treatment, and not simply a failure to act. The failure or refusal to take forward a human rights issue such as accommodation of a disability in the workplace is not, in and of itself, a breach of the Code. There must be a claim, and a factual foundation for the claim, that the failure to act was based on discriminatory factors.” + 23 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals In numerous cases the Tribunal emphasizes that the decision not to act must be based on discriminatory factors. In Baylet v. Universal Workers Union, 2009 HRTO 700 paras 17-19 “To found a claim against the Union, the applicant must provide a factual basis that could give rise to a finding that it discriminated against him. For example, the applicant could allege that the Union interfered with the accommodation process or made its decision not to represent the applicant because of discriminatory factors. Both of these assertions would require a factual underpinning.” (emphasis added) “One can not presume that a union's failure to act was based on discriminatory beliefs. There may be many reasons why a union might choose not to pursue a human rights claim on behalf of an employee that have no discriminatory overtones.” + 24 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals In Gungor the Tribunal states that “[t]he issue for union liability under s.6 (membership) is whether there is a discriminatory basis or factor involved in a union’s conduct in relation to its representation of a union member” Gungor para 58 + 25 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals Sometimes a slightly broader formulation is used. In Choa v. CUPE, 2013 HRTO 199 the Tribunal stated: “The Tribunal does not have the power to deal with general allegations of unfair treatment by unions or employee associations. For example, the Tribunal has found that it is not discrimination for a union or an employee association to decide not to pursue a grievance, or address a member's issues, unless its decision is linked, in whole or in part, to a prohibited ground of discrimination under the Code”. The Tribunal then went on to quote from Traversy. + 26 Claims Against Unions Before Human Rights Tribunals Do these formulations leave room for indirect discrimination scenarios? Does this leave out scenarios where a union’s decision not to pursue a grievance (or otherwise not to act) has a differential impact based on a prohibited ground, but the decision itself is not premised on the prohibited ground? The Traversy formulation suggests that differential treatment is the issue, and that it only runs afoul of the HRC only if the decision is not to act is based on a prohibited ground. Is this limitation intentional, given that every decision not to act could constitute differential treatment? + 27 Jurisdiction as Between LRBs and HRTs The human rights tribunals’ analysis hints at the their preference that issues relating to union discrimination to be dealt with by the LRBs. (see Traversy, supra; Arias v. Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples, 2009 HRTO 1025; Baylet v. Universal Workers Union, 2009 HRTO 700, Gungor supra.) The HRTO considers DFR proceedings before the OLRB to be “another proceedings” for the purposes of s.45.1 of the Code, and may thus defer or dismiss applications which were “appropriately dealt with” by the OLRB. The HRTO also considers settlements of DFR claims to constitute “another proceeding” for the purposes of s.45.1. – Dunn v Sault Ste Marie (City), 2008 HRTO 149. + 28 Jurisdiction as Between LRBs and HRTs The LRBs also understand themselves to have concurrent jurisdiction with the HRTs. The LRBs jurisprudence appears to be a bit more exacting than before the HRTO as regards discriminatory conduct by unions. The LRBs do generally require some sort of justification for inaction, which so far the HRTO does not appear to. + 29 Have Unions Representational Obligations Changed Post-Weber? The DFR doesn’t appear to have changed significantly since Weber. The HRTs would prefer that the LRBs deal with questions about unions’ discrimination, but it’s not clear that the LRBs want to do so. The early consequence of Weber regarding human rights was the proliferation of jurisdictional disputes in multiple fora. Concurrency, even as controlled by the Figliola/Penner principles, does not appear to have reduced the issue of multiple claims, at least as regards the quality of unions’ representation. Everyone seems to be defending themselves everywhere, even if just briefly to get a res judicata dismissal. + 30 Further Empirical Research is Needed Are there more DFR claims now than prior to Weber? + BC LRB Annual Reports From the BCLRB Annual Report 2008 Graph from 2008 report 2008-2010 – approx 100 DFR cases a year. 2011 – 2012 – approx 60 DFR cases 2013 – 54 DFR cases 2014 – 70 DFR cases 31 + 32 Further Empirical Research is Needed How often is a DFR claim accompanied by a human rights claim to the HRTs? Have unions changed the way they decide whether to bring a grievance when a human rights issue is at stake? Do they consider different factors than as regards other types of grievances? Have the factors changed since Weber? Has there been an increase in CBA provisions and/or union policies requiring the grievance of all dismissals? If so, are such terms/policies implemented so as to protect unions from DFRs relating to human rights issues, or just as ‘critical interests’ protection? + 33 Further Empirical Research is Needed Occasionally the case law suggests that a union is bringing a claim to the HR Tribunal on behalf of a member. When would this occur instead of going to arbitration? More frequently the facts of a case suggest that the union is operating in the background. What role are they taking here? Unions sometimes also intervene in human rights claims by employees against their ERs. Unions sometime try and split their claims before before arbitration and human rights tribunals When does this occur? How often does this occur? What has been the success of this approach? E. Shilton, Choice but No Choice, suggests this is generally a fruitless endeavour. Is there a difference in the number of claims brought against unions to the HRTs in direct access model provinces? + 34 Further Empirical Research is Needed How are unions dealing with their representational responsibilities where the alleged discrimination arises between union members? What processes are in place, if any, to ensure that both members receive appropriate union support? Are there more of such claims since Weber? This issue is largely invisible in the case law, but is one worthy of discussion. + 35 Further Empirical Research is Needed The value of the union veto: Part of the original rationale for the union veto was to allow unions to make choices for the benefit of the collective, and to give employers confidence in the finality of decisionmaking at arbitration. Given the realities of concurrency, and of multiple proceedings, does the veto still really lead to finality in decision-making? What effect has concurrent jurisdiction had on union-management relations? If finality is attenuated, has the value of the union veto become largely illusory? + 36 Some Concluding Thoughts Generally, the facts of most of the DFR and human rights cases against unions seem unmeritorious, but there are situations where the EE does have a significant human rights issue that a union has ignored. How to craft a jurisprudential standard to catch the real issues when they arise, while reducing the load created by the rest? Whether or not the claims are meritorious, and even as controlled by the Figliola/Penner principles, everyone seems to be defending themselves everywhere. + 37 Some Concluding Thoughts Subject to the empirical research just proposed, if the union veto does not actually create finality, what is its purpose? If finality is illusory, and there is such difficulty in getting the jurisprudential balance right between meritorious and unmeritorious DFR/HR claims, perhaps Bernie’s early suggestion now makes a lot of sense: Where a union refuses to advance a grievance regarding human rights, let members bring the grievance and pay for it themselves. This will relieve the pressure of DFR claims and part of the concurrency issues.