Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs)

advertisement

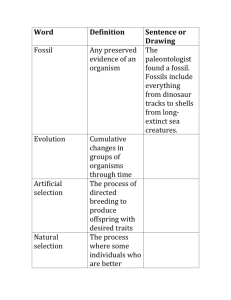

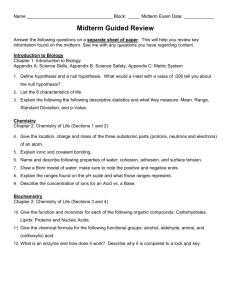

Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs) http://www.livescience.com/animals/top10_vestigial_organs.html • • • • • In Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) and his next publication, The Descent of Man (1871), he referred to several "vestiges" in human anatomy that were left over from the course of evolution. These vestigial organs, Darwin argued, are evidence of evolution and represent a function that was once necessary for survival, but over time that function became either diminished or nonexistent. The presence of an organ in one organism that resembles one found in another has led biologists to conclude that these two might have shared a common ancestor. Vestigial organs have demonstrated remarkably how species are related to one another, and has given solid ground for the idea of common descent to stand on. From common descent, it is predicted that organisms should retain these vestigial organs as structural remnants of lost functions. It is only because of macro-evolutionary theory, or evolution that takes place over very long periods of time, that these vestiges appear. The term "vestigial organ" is often poorly defined, most commonly because someone has chosen a poor source to define the term. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines vestigial organs as organs or structures remaining or surviving in a degenerate, atrophied, or imperfect condition or form. This is the accepted biological definition used in the theory of evolution. In the never-ending search for scientific truth, hypotheses are proposed, evidence is found, and theories are formulated to describe and explain what is being observed in the world around us. The following are ten observations of vestigial organs whose presence have helped to flesh out the structure of the family tree that includes every living creature on our planet. -- Brandon Miller The Wings on Flightless Birds • The Cassowary, the sexier, but lesswell-known flightless bird. In 1798, sixty years before Charles Darwin's first book was published, a French anatomist, Étienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire, traveled to Egypt with Napoleon where he witnessed and wrote about a flightless bird whose wings appeared useless for soaring. The bird that Hilaire described was an ostrich, but he described it as a "cassowary", a term used back then to describe various birds of ostrich-like appearance. Ostriches and cassowaries are among several birds that have wings that are vestigial. Besides the cassowary, other flightless birds with vestigial wings are the kiwi, and the kakapo (the only known flightless and nocturnal parrot), among others. In general, wings of a bird are considered complex structures that are specifically adapted for flight and those belonging to these flightless birds are no different. They are, anatomically, rudimentary wings, but they could never give these bulky birds flight. The wings are not completely useless, as they are used for balance during running and in flagging down the honeys during courtship displays. Hind Leg Bones in Whales • Whale skeleton showing pelvis and thigh bones (see inset). Biologists believe that for 100 million years the only vertebrates on Earth were waterdwelling creatures, with no arms or legs. At some point these "fish" began to develop hips and legs and eventually were able to walk out of the water, giving the earth its first land lovers. Once the land-dwelling creatures evolved, there were some mammals that moved back into the water. Biologists estimate that this happened about 50 million years ago, and that this mammal was the ancestor of the modern whale. Despite the apparent uselessness, evolution left traces of hind legs behind, and these vestigial limbs can still be seen in the modern whale. There are many cases where whales have been found with rudimentary hind limbs in the wild, and have been found in baleen whales, humpback whales, and in many specimens of sperm whales. Most of these examples are of whales that had only leg bones, but there were some that included feet with complete digits. It was reported recently that whales and hippos were distantly related. Erector Pili and Body Hair • When a rabbit is scared, its hair stands on end. When a human is scared, he or she calls the police. The erector pili are smooth muscle fibers that give humans "goose bumps." If the erector pili are activated, the hairs that come out of the nearby follicles stand up and give an animal a larger appearance that might scare off potential enemies and a coat that is thicker and warmer. Humans, though, don't have thick furs like their ancestors did, and our strategy for several thousand years has been to take the fur off other warm looking animals to stay warm. It's ironic actually that an animal, sensing danger is near, would puff up its coat to look scarier, but the human hunter would see the puffier coat as a warm prize, leaving the thinner haired weaker looking animals alone. Of course, some body hair is helpful to humans; eye brows can keep sweat out of the eyes and facial hair might influence a woman's choice of sexual partner. All the rest of that hair, though, is essentially useless. The Human Tailbone (Coccyx) • The human tailbone doesn't do much, but really hurts if you land on it. These fused vertebrae are the only vestiges that are left of the tail that other mammals still use for balance, communication, and in some primates, as a prehensile limb. As our ancestors were learning to walk upright, their tail became useless, and it slowly disappeared. It has been suggested that the coccyx helps to anchor minor muscles and may support pelvic organs. However, there have been many well documented medical cases where the tailbone has been surgically removed with little or no adverse effects. There have been documented cases of infants born with tails, an extended version of the tailbone that is composed of extra vertebrae. There are no adverse health effects of such a tail, unless perhaps the child was born in the Dark Ages. In that case, the child and the mother, now considered witches, would've been killed instantly. The Blind Fish Astyanax Mexicanus • Astyanax mexicanus: growing up in the wrong neighborhood. In an experiment designed by nature, the species of fish known as Astyanax mexicanus, dwelling in caves deep underground off the coast of Mexico, cannot see. The pale fish has eyes, but as it is developing in the egg, the eyes begin to degenerate, and the fish is born with a collapsed remnant of an eye covered by flap of skin. These vestigial eyes probably formed after hundreds or even thousands of years of living in total darkness. As for the experiment, a control is needed; and luckily for us, fish of the same species live right above, near the surface, where there is plenty of light, and these fish have fully functioning eyes. To test if the eyes of the blind mexicanus could function if given the right environment, scientists removed the lens from the eye of the surface-dwelling fish and implanted it into the eye of the blind fish. It was observed that within eight days an eye started to develop beneath the skin, and after two months the fish had developed a large functioning eye with a pupil, cornea, and iris. The fish were blind, but now they see. Wisdom Teeth in Humans • They need regular brushing. With all of the pain, time, and money that are put into dealing with wisdom teeth, humans have become just a little more than tired of these remnants from their large jawed ancestors. But regardless of how much they are despised, the wisdom teeth remain, and force their way into mouths regardless of the pain inflicted. There are two possible reasons why the wisdom teeth have become vestigial. The first is that the human jaw has become smaller than its ancestors' and the wisdom teeth are trying to grow into a jaw that is much too small. The second reason may have to do with dental hygiene. A few thousand years ago, it might be common for an 18 year old man to have lost several, probably most, of his teeth, and the incoming wisdom teeth would prove useful. Now that humans brush their teeth twice a day, it's possible to keep one's teeth for a lifetime. The drawback is that the wisdom teeth still want to come in, and when they do, they usually need to be extracted to prevent any serious pain. The Sexual Organs of Dandelions • Send in the clones ... Dandelions, like all flowers, have the proper organs (stamen and pistil) necessary for sexual reproduction, but do not use them. Dandelions reproduce without fertilization; they basically clone themselves, and they are quite successful at it. Look at any lawn for the proof. If dandelions were to revert to sexual reproduction, they might not retain whatever traits they have that allow them to be pests to gardeners everywhere. If flowers can begin reproducing in this manner, does that mean animals, even humans could too? Asexual reproduction can be a good strategy in an environment that is constant if a species is well suited to those conditions. It doesn't take a scientist to figure out that humans wouldn't last long if the condition set forth was no sexual contact with others. Therefore, the human sexual organs are probably in no danger of becoming vestigial. Fake Sex in Virgin Whiptail Lizards (Vestigial Behavior) • Feminist lizards take the male out of the picture. Only females exist in several species of the lizards of the genus Cnemidophorus, which might seem like a problem when it comes time to propagate the species. The females don't need the males though, they reproduce by parthenogenesis, a form of reproduction in which an unfertilized egg develops into a new individual. So basically, the females don't need the males; they just produce clones of themselves as a form of reproduction. Despite the fact that it is unnecessary and futile to attempt copulation with each other, the lizards still like to try, and occasionally one of the females will start to "act like a male" by attempting to copulate with another female. The lizards evolved from a sexual species and the behavior to copulate like a male -- to engage in fake sex -- is a vestigial behavior; that is, a behavior present in a species, but is expressed in an imperfect form, which in this case, is useless. Male Breast Tissue and Nipples • Oh yeah, really handy those ... The subject of male nipples is a sensitive, and maybe confusing, topic to many. Those who wish to invalidate evolutionary theory might pose the question, "Was man descended from woman?" The answer, of course, is no. Both men and women have nipples because in early stages of fetal development, an unborn child is effectively sexless. Nipples are present in both males and females; it is only in a later stage of fetal development that testosterone causes sex differentiation in a fetus. All mammals, male and female, have mammary glands. Male nipples are vestigial; they may perform a small role in sexual stimulation and a small number of men have been able to lactate. However, they are not fully functional and, because cancer can grow in male or female breast tissue, the tissue can be dangerous. The Human Appendix • Leonardo da Vinci's sketch of the intestines that included the appendix. In plant-eating vertebrates, the appendix is much larger and its main function is to help digest a largely herbivorous diet. The human appendix is a small pouch attached to the large intestine where it joins the small intestine and does not directly assist digestion. Biologists believe it is a vestigial organ left behind from a plant-eating ancestor. Interestingly, it has been noted by paleontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer in his text The Vertebrate Body (1949) that the major importance of the appendix "would appear to be financial support of the surgical profession," referring to, of course, the large number of appendectomies performed annually. In 2000, in fact, there were nearly 300,000 appendectomies performed in the United States, and 371 deaths from appendicitis. Any secondary function that the appendix might perform certainly is not missed in those who had it removed before it might have ruptured. Duke University Medical Center. "Appendix Isn't Useless At All: It's A Safe House For Good Bacteria." ScienceDaily 8 October 2007. 28 May 2009 <http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2007/10/071008102334.htm>. • • Appendix Isn't Useless At All: It's A Safe House For Good Bacteria ScienceDaily (Oct. 8, 2007) — Long denigrated as vestigial or useless, the appendix now appears to have a reason to be – as a "safe house" for the beneficial bacteria living in the human gut. • Drawing upon a series of observations and experiments, Duke University Medical Center investigators postulate that the beneficial bacteria in the appendix that aid digestion can ride out a bout of diarrhea that completely evacuates the intestines and emerge afterwards to repopulate the gut. • "While there is no smoking gun, the abundance of circumstantial evidence makes a strong case for the role of the appendix as a place where the good bacteria can live safe and undisturbed until they are needed," said William Parker, Ph.D., assistant professor of experimental surgery, who conducted the analysis in collaboration with R. Randal Bollinger, M.D., Ph.D., Duke professor emeritus in general surgery. The appendix is a slender two- to four-inch pouch located near the juncture of the large and small intestines. While its exact function in humans has been debated by physicians, it is known that there is immune system tissue in the appendix. The gut is populated with different microbes that help the digestive system break down the foods we eat. In return, the gut provides nourishment and safety to the bacteria. Parker now believes that the immune system cells found in the appendix are there to protect, rather than harm, the good bacteria. For the past ten years, Parker has been studying the interplay of these bacteria in the bowels, and in the process has documented the existence in the bowel of what is known as a biofilm. This thin and delicate layer is an amalgamation of microbes, mucous and immune system molecules living together atop of the lining the intestines. "Our studies have indicated that the immune system protects and nourishes the colonies of microbes living in the biofilm," Parkers explained. "By protecting these good microbes, the harmful microbes have no place to locate. We have also shown that biofilms are most pronounced in the appendix and their prevalence decreases moving away from it." This new function of the appendix might be envisioned if conditions in the absence of modern health care and sanitation are considered, Parker said. "Diseases causing severe diarrhea are endemic in countries without modern health and sanitation practices, which often results in the entire contents of the bowels, including the biofilms, being flushed from the body," Parker said. He added that the appendix's location and position is such that it is expected to be relatively difficult for anything to enter it as the contents of the bowels are emptied. "Once the bowel contents have left the body, the good bacteria hidden away in the appendix can emerge and repopulate the lining of the intestine before more harmful bacteria can take up residence," Parker continued. "In industrialized societies with modern medical care and sanitation practices, the maintenance of a reserve of beneficial bacteria may not be necessary. This is consistent with the observation that removing the appendix in modern societies has no discernable negative effects." Several decades ago, scientists suggested that people in industrialized societies might have such a high rate of appendicitis because of the so-called "hygiene hypothesis," Parker said. This hypothesis posits that people in "hygienic" societies have higher rates of allergy and perhaps autoimmune disease because they -and hence their immune systems -- have not been as challenged during everyday life by the host of parasites or other disease-causing organisms commonly found in the environment. So when these immune systems are challenged, they can over-react. "This over-reactive immune system may lead to the inflammation associated with appendicitis and could lead to the obstruction of the intestines that causes acute appendicitis," Parker said. "Thus, our modern health care and sanitation practices may account not only for the lack of a need for an appendix in our society, but also for much of the problems caused by the appendix in our society." Parker conducted a deductive study because direct examination the appendix's function would be difficult. Other than humans, the only mammals known to have appendices are rabbits, opossums and wombats, and their appendices are markedly different than the human appendix. Parker's overall research into the existence and function of biofilms is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Other Duke members of the team were Andrew Barbas, Errol Bush, and Shu Lin. This theory appears online in the Journal of Theoretical Biology. Adapted from materials provided by Duke University Medical Center. • • • • • • • • • • • • •