Ovid's Apollo and Daphne

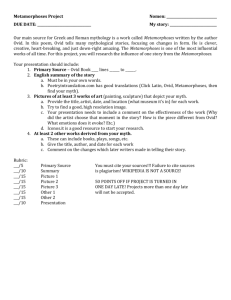

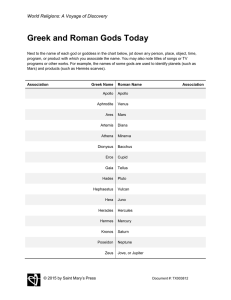

Apollo and Daphne

Ovid

, Metamorphoses

I.452-567

Sarah Ellery

Final Teaching Project

UGA Summer Institute, 2013

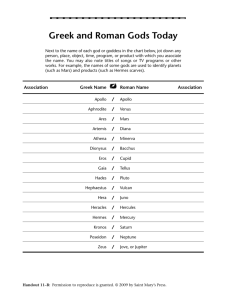

Apollo and Daphne , Bernini,

1622-25; Galleria Borghese, Rome

Credit: galleriaborghese.it

PUBLIUS OVIDIUS NASO (43 B.C. – A.D. 17/18)

•

43 BC Born 20 March at Sulmo (modern

Sulmona).

• c.31 Ovid and his elder brother (by exactly one year) taken or sent to Rome to continue their education; they are granted by Augustus the rank of equites .

• c.27 Ovid assumes the toga virilis . He marries.

• c.25

Ovid’s patron is now Marcus Valerius

Messalla Corvinus (64 BC-AD 8). He gives his first public reading. End of his formal education in rhetoric, and of his first marriage.

•

24

Death of Ovid’s brother.

• c.24-22 Ovid travels in Greece, Asia Minor, and

Sicily, with the poet Macer as tutor.

Statue of Ovid in Constanza.

Romania (ancient Tomis)*

Source: www.the-romans.co.uk/timelines/ovid.htm

* Unless otherwise specified, all images are from

Wikimedia Commons.

• c.22

Trains in public administration and law.

• c.21-c.16 Sits on various boards, including the tresviri and the decemviri stlitibus iudicandis . He is close friends with the poet Propertius.

• c.15 Publishes Amores.

Marries for the second time, and has a daughter. The marriage is brief, possibly owing to the death of his wife.

• c.14-c.1

Writes Ars Amatoria, Remedia Amoris , Heroides , and Medicamine Faciei

Feminae , dividing his time between Rome and his country villa a few miles outside the city.

•

1 Publishes first two books of Ars Amatoria

. c.1 Death of Ovid’s father, aged 90.

•

AD c.1

Ovid’s third marriage. His wife, who is well connected and may have been in her early 20s, already has a daughter by her first husband.

• c.1-8 Writes Metamorphoses . Begins

Fasti .

•

8 Banished by Augustus to Tomi.

•

9-17 In exile, completes Fasti , of which only six books survive, and writes Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto .

•

17/18 Dies during the winter, in his 60th year, and is buried on the shore of the

Black Sea.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

•

Epic in 15 books

•

Bound by the theme of change:

In nova fert animus mūtātās dīcere formās corpora: dī, coeptīs (nam vōs mūtāstis et illa) adspīrāte meīs prīmāque ab orīgine mundī ad mea perpetuum dēdūcite tempora carmen.

Metamorphoses I.1-4

My mind compels me to tell of forms changed into new bodies. Gods, favor my undertakings—for you have changed them, as well—and spin out a continuous poem, from the first origin of the world to my own day.

Structure of Book I

•

Prologue

•

Creation

•

The Four Ages

•

The Giants

•

Lycaon

•

The Flood

•

Deucalion and Pyrrha

•

Python

•

DAPHNE

•

Io

–

Interlude: Pan and Syrinx

•

Phaethon

Click here to read Book I in translation

“Apollo and Daphne”

• First “met AMOR phosis” in the first book of the epic

– Apollo as elegiac lover

•

Reminiscent of Amores I.1

– subject: Cupid and Apollo

– verbal echoes

– playful tone

– see further discussion after section IV, “What Woman Could Resist?”

•

Etiological

– reward for Pythian Games

A Few Notes on Ovid’s Style

•

Poetic grammatical forms:

–

-ēre for ērunt

– “poetic” plural

– preference for que over et

–

-īs for ēs

• Vivacious, free flowing narrative

–

Vivid present

–

Metrically swift, few elisions

•

Compact sense units

– couplets (cf. elegy)

– close relationship between the verb / participle and the noun-adjective group

– caesura employed to clarify narrative rather than to create an emphatic break

• Vocabulary

–

Look for the ways Ovid repeats and repurposes vocabulary among and within his stories. His word choice can provide the reader a thread with which to follow the labyrinth of interconnected themes, motifs, etc. throughout the whole work.

I. Two Archers

455

460 juxtaposition

Prīmus amor Phoebī Daphnē Pēnēia: quem nōn fors ignāra dedit, sed saeva Cupīdinis īra.

Dēlius hunc nūper victō serpente superbus, vīderat adductō flectentem cornua nervō

“Quid” que ‘tibi, lascīve puer, cum fortibus armīs?”

Dīxerat, “Ista decent umerōs gestāmina nostrōs, quī dare certa ferae, dare vulnera possumus hostī, quī modo pestiferō tot iūgera ventre prementem strāvimus innumerīs tumidum Pȳthōna sagittīs.

Tū face nesciō quōs estō contentus amōrēs inrītāre tuā, nec laudēs adsere nostrās.” alliteration epithet nostrōs : “royal” we synchesis

Pȳthōna

: Greek acc.

estō: future imperative

I. Two Archers

465

470

Fīlius huic Veneris “Fīgat tuus omnia, Phoebe, tē meus arcus” ait, “quantōque animālia cēdunt cūncta deō, tantō minor est tua glōria nostrā.”

Dīxit et ēlīsō percussīs āēre pennīs inpiger umbrōsā Parnāsī cōnstitit arce ēque sagittiferā prōmpsit duo tēla pharetrā dīversōrum operum: fugat hoc, facit illud amōrem; quod facit, aurātum est et cuspide fulget acūtā, quod fugat, obtūsum est et habet sub harundine plumbum. epithet synchesis alliteration word picture prodelision

KNOW THYSELF

* Does Apollo heed this advice in this story?

According to the ancient travel writer Pausanias, this ancient Greek aphorism was inscribed on the pronaos (forecourt) of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Pictured left is Apollo’s temple at Delphi, which is situated on Mt. Parnassus in central Greece.

At the right is the Omphalos, or navel of the world, from the sanctuary at Delphi.

Credits: Livius.org (left); Wikimedia Commons (right)

Silver Drachm of Seleukos IV

Antioch mint, ca. 187 - 175 BCE

Credit: Wesleyan.edu (Dahl Coin Collection)

OBVERSE: Seleukos IV REVERSE: Apollo, seated on the omphalos with bow and arrow

Apollo as Archer

(Apollo Saettante)

Roman, 100 B.C.–before A.D. 79.

Discovered in Pompeii in A.D.

1817-18.

Credit: blogs.getty.edu

Apollo, Attic Red Figure krater ca. 475-425 B.C.

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Apollo is pictured drawing his bow, about to kill the Niobides.

Note the laurel crown and the pharetra hanging at his side.

Credit: theoi.com

II. The Arrows Fly

475

480

Hoc deus in nymphā Pēnēide fīxit, at illō laesit Apollineās trāiecta per ossa medullās: prōtinus alter amat, fugit altera nōmen amantis silvārum latebrīs captīvārumque ferārum exuviīs gaudēns innūptaeque aemula Phoebēs; vitta coercēbat positōs sine lēge capillōs.

Multī illam petiēre, illa āversāta petentēs inpatiēns expersque virī nemora āvia lustrat nec, quid Hymēn, quid Amor, quid sint cōnūbia cūrat. patronymic

Apollineās: neologism synchesis synchesis anaphora, tricolon

Girl wearing the vitta , or headband. From

William Smith’s

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities .

Credit: LacusCurtius.org

II. The Arrows Fly

485

Saepe pater dīxit “Generum mihi, fīlia, dēbēs”, saepe pater dīxit “dēbēs mihi, nāta, nepōtēs”: illa velut crīmen taedās exōsa iugālēs pulchra verēcundō suffūderat ōra rubōre inque patris blandīs haerēns cervīce lacertīs,

“Dā mihi perpetuā, genitor cārissime,” dīxit

“virginitāte fruī: dedit hoc pater ante Diānae.”

Ille quidem obsequitur; sed tē decor iste, quod optās, esse vetat, vōtōque tuō tua forma repugnat.

anaphora, synchesis,

2x chiasmus

“golden line” word picture alliteration polyptoton: the repetition of a word or root in different grammatical forms within the same sentence.

“Golden Line”

The golden line is variously defined, but most uses of the term conform to the oldest known definition from Burles' Latin grammar of 1652:

If the Verse does consist of two Adjectives, two Substantives and a Verb only, the first Adjective agreeing with the first Substantive, the second with the second, and the Verb placed in the midst, it is called a Golden Verse: as, a b V A B

Lurida terribiles miscent aconita novercae (Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.147)

“murderous stepmothers mixed deadly aconite” a b V A B aurea purpuream subnectit fibula vestem

"a golden clasp bound her purple cloak”

(Virgil, Aeneid 4.139)

Here the adjectives (a, b) are placed at the beginning of the line, and the nouns

(A, B) at the end.

Note that in each case the synchesis is purposeful, emphasizing the meaning of the line ( mixing poison and binding a cloak).

“Golden Line”

•

The term "golden line" did not exist in antiquity.

•

Winbolt, the most thorough commentator on the golden line, described the golden line as a combination of poetic tendencies in

Latin hexameter– the preference for placing adjectives near the beginning of the line and nouns emphatically near the end.

•

The golden line is a form of hyperbaton, or the deviation from normal or logical word order for poetic effect.

•

Some scholars also consider lines with a chiastic pattern to be

“golden” (a-b-V-B-A), but others instead call this a “silver line”.

“Golden Line”

K. Mayer, "The Golden Line: Ancient and Medieval Lists of Special Hexameters and Modern Scholarship," in C. Lanham, ed., Latin Grammar and Rhetoric: Classical Theory and Modern Practice, Continuum Press,

2002, pp. 139-179 .

III. Apollo in Love

490 Phoebus amat vīsaeque cupit cōnūbia Daphnēs, quodque cupit, spērat, suaque illum ōrācula fallunt; utque levēs stipulae dēmptīs adolentur aristīs, ut facibus saepēs ardent, quās forte viātor

495 vel nimis admōvit vel iam sub lūce relīquit, sīc deus in flammās abiit, sīc pectore tōtō ūritur et sterilem spērandō nūtrit amōrem.

Spectat inōrnātōs collō pendēre capillōs et “Quid, sī cōmantur?” ait;

Daphnēs:

Gk. gen.

irony epic simile

III. Apollo in Love

Note the placement of videt, laudat, and fugit at the beginning of their clauses. What is the effect?

500

505 videt igne micantēs sīderibus similēs oculōs, videt ōscula, quae nōn est vīdisse satis; laudat digitōsque manūsque bracchiaque et nūdōs mediā plūs parte lacertōs: sīqua latent, meliōra putat. Fugit ōcior aurā illa levī neque ad haec revocantis verba resistit:

“Nympha, precor, Pēnēi, manē! Nōn īnsequor hostis; nympha, manē! Sīc agna lupum, sīc cerva leōnem, sīc aquilam pennā fugiunt trepidante columbae, hostēs quaeque suōs; amor est mihi causa sequendī.

metaphor simile, anaphora, alliteration litotes, polysyndeton chiasmus synchesis

Pēnēi:

Gk. voc.

(not a dipthong) anaphora, synchesis, simile, tricolon

EKPHRASIS

:

description in literary works, often used in epic

•

Often uses highly visual language

–

What visual cues does Ovid give in this story?

•

Gives the reader a “gaze”, often through an internal viewer

–

cf. Temple of Juno in Bk. I of the Aeneid

–

Through whose gaze do we “see” Daphne?

IV. What Woman Could Resist?

510

515

“Mē miserum! Nē prōna cadās, indignave laedī crūra notent sentēs, et sim tibi causa dolōris.

Aspera, quā properās, loca sunt: moderātius, orō, curre fugamque inhibē: moderātius īnsequar ipse.

Cui placeās, inquīre tamen; nōn incola montis, nōn ego sum pāstor, nōn hīc armenta gregēsque horridus observō. Nescīs, temerāria, nescīs, quem fugiās, ideōque fugis. Mihi Delphica tellūs et Claros et Tenedos Patarēaque rēgia servit;

Nē

: take with cadās

(2 nd person jussive = imperative), notent , sim tricolon anaphora tricolon, anaphora epizeuxis polyptoton polysyndeton epizeuxis - repetition of words or phrases with few or no words between e.g. “Please Please Me” –The Beatles

IV. What Woman Could Resist?

520

Iūppiter est genitor. Per mē, quod eritque fuitque estque, patet; per mē concordant carmina nervīs.

Certa quidem nostra est, nostrā tamen ūna sagitta certior, in vacuō quae vulnera pectore fēcit.

Inventum medicīna meum est, opiferque per orbem dīcor, et herbārum subiecta potentia nōbīs: ei mihi, quod nūllīs amor est sānābilis herbīs, nec prōsunt dominō, quae prōsunt omnibus, artēs!” anaphora alliteration prodelision enjambment, polyptoton prodelision

nōbīs: dat. w/ subiecta irony

Review :

Look again at Apollo’s speech, and find examples of caesura and diaeresis .

Why might there be so many breaks in these lines compared to the narration?

How did Apollo come to have the lyre?

•

Hermes, the herald of the Olympian gods, is the son of Zeus and the nymph

Maia, daughter of Atlas and one of the Pleiades. Hermes is the god of shepherds, land travel, merchants, weights and measures, oratory, literature, athletics and thieves, and known for his cunning and shrewdness. Most importantly, he is the messenger of the gods. Besides that he was also a minor patron of poetry. He was worshiped throughout Greece -- especially in Arcadia -- and festivals in his honor were called Hermoea.

•

According to legend, Hermes was born in a cave on Mount Cyllene in

Arcadia. Zeus had impregnated Maia at the dead of night while all other gods slept. When dawn broke amazingly he was born. Maia wrapped him in swaddling bands, then, resting herself, fell fast asleep. Hermes, however, squirmed free and ran off to Thessaly. This is where Apollo, his brother, grazed his cattle. Hermes stole a number of the herd and drove them back to Greece. He hid them in a small grotto near to the city of Pylos and covered their tracks.

•

Before returning to the cave he caught a tortoise, killed it and removed its entrails. Using the intestines from a cow stolen from Apollo and the hollow tortoise shell, he made the first lyre. When he reached the cave he wrapped himself back into the swaddling bands.

•

When Apollo realized he had been robbed he protested to Maia that it had been Hermes who had taken his cattle. Maia looked to Hermes and said it could not be, as he is still wrapped in swaddling bands. Zeus the allpowerful intervened saying he had been watching and Hermes should return the cattle to Apollo. As the argument went on, Hermes began to play his lyre. The sweet music enchanted Apollo, and he offered Hermes to keep the cattle in exchange for the lyre.

•

Apollo later became the grand master of the instrument, and it also became one of his symbols. Later while Hermes watched over his herd he invented the pipes known as a syrinx (pan-pipes), which he made from reeds.

Hermes was also credited with inventing the flute. Apollo also desired this instrument, so Hermes bartered with Apollo and received his golden wand, which Hermes later used as his heralds staff. (In other versions Zeus gave

Hermes his heralds staff).

Source: Ron Leadbetter, pantheon.org

HERMES APOLLO HERAKLES

Attic Red Figure Kylix, ca. 500 B.C.; Antikenmuseen, Berlin, Germany

Elegiac Poetry

•

elegiac couplet (hexameter / pentameter)

- u u | - u u | - u u | - u u | - u u | - -

- u u | - u u | - || - u u | - u u | -

•

Greek origins

•

most popular type of poetry in Ovid’s Rome

–

Catullus, Propertius, Tibullus

•

love is common theme

–

paraclausithyron, exclusus amator

Read Amores I.1

(click for link)

V. The Pace Quickens

525

530

Plūra locūtūrum timidō Pēnēia cursū fūgit cumque ipsō verba inperfecta relīquit, tum quoque vīsa decēns; nūdābant corpora ventī, obviaque adversās vibrābant flāmina vestēs, et levis inpulsōs retrō dabat aura capillōs, auctaque forma fugā est. Sed enim nōn sustinet ultrā perdere blanditiās iuvenis deus, utque monēbat ipse amor, admissō sequitur vestīgia passū.

locūtūrum (eum) golden line!

alliteration prodelision amor (or Amor !)

V. The Pace Quickens

535 epic simile

Ut canis in vacuō leporem cum Gallicus arvō vīdit, et hic praedam pedibus petit, ille salūtem

(alter inhaesūrō similis iam iamque tenēre spērat et extentō stringit vestīgia rostrō, alter in ambiguō est, an sit conprēnsus, et ipsīs morsibus ēripitur tangentiaque ōra relinquit): sīc deus et virgō; est hic spē celer, illa timōre.

word picture enjambment, synchesis epizeuxis an : introduces a deliberative synchesis 2x

What is the Greek middle voice?

subject performs AND receives the action of the verb

What does Latin use instead?

reflexive pronoun

VI. Daphne’s Last Request

540 Quī tamen īnsequitur, pennīs adiūtus amōris, ōcior est requiemque negat tergōque fugācis inminet et crīnem sparsum cervīcibus adflat.

Vīribus absūmptīs expalluit illa citaeque

544a

545 victa labōre fugae “Tellūs,” ait, “hīsce vel istam,

[victa labōre fugae spectāns Pēnēidās undās] quae facit ut laedar, mutandō perde figūram!

polysyndeton enjambment istam (figuram)

VI. Daphne’s Last Request

547a

550

Fer, pater,” inquit “opem, sī flūmina nūmen habētis! quā nimium placuī, mutandō perde figūram!”

[quā nimium placuī, Tellūs, ait, hīsce vel istam]

Vix prece fīnītā torpor gravis occupat artūs: mollia cinguntur tenuī praecordia librō, in frondem crīnēs, in rāmōs bracchia crēscunt; pēs modo tam vēlōx pigrīs rādīcibus haeret, ōra cacūmen habet: remanet nitor ūnus in illā.

scan internal rhyme quā (figuram) synchesis antithesis

Credit: nga.gov

* Note that Daphne’s prayer, like Apollo’s to her, has many caesurae and diaereses. Why?

Pollaiuolo: Apollo and Daphne

• Antonio del Pollaiuolo, late

15 th century; oil on wood;

The National Gallery,

London

• Renaissance: classicizing, allegory

• What aspects of this portrayal are similar to or different from the Ovidian version?

• What are the limitations in portraying this myth visually?

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne

•

Gian Lorenzo Bernini,

1622-25; Rome,

Galleria Borghese

•

Baroque: reaction against the pure, straight lines of the

Classical period

Click to view the sculpture in the round

(narration in Italian)

Credit:

Cavetocanvas.com

Credit: www.mcah.columbia.edu

Credits: www.mcah.columbia.edu

Apollo Belvedere

• Roman copy of a Greek original by Leochares, ca.

120-140 (Hadrianic); Rome,

Vatican Museum.

• Compare this Apollo’s staid posture and classical lines with his portrayal by Bernini.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

(1598-1680)

Self portrait, ca. 1623

Rome: Galleria Borghese

Baroque Architecture : Baldacino, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Baroque Architecture : Bernini, Fontana dei Quattro Fiume,

Piazza Navona, Rome

Baroque Architecture : Trevi Fountain, Rome

Baroque Music :

1685-1750

VII. Apollo’s Eternal Love

555

Hanc quoque Phoebus amat positāque in stīpite dextrā sentit adhūc trepidāre novō sub cortice pectus conplexusque suīs ramos, ut membra, lacertīs ōscula dat lignō: refugit tamen ōscula lignum.

Cui deus “At quoniam coniūnx mea nōn potes esse, arbor eris certē” dīxit “mea. Semper habēbunt tē coma, tē citharae, tē nostrae, laure, pharetrae; word pictures… note the placement of the anatomical words chiasmus, synchesis, polypton, epizeuxis alliteration anaphora www.theoi.com

VII. Apollo’s Eternal Love

560 tū ducibus Latiīs aderis, cum laeta triumphum vōx canet et vīsent longās Capitōlia pompās.

Postibus Augustīs eadem fīdissima custōs ante forēs stābis mediamque tuēbere quercum,

565 utque meum intōnsīs caput est iuvenāle capillīs, tū quoque perpetuōs semper gere frondis honōrēs.”

Fīnierat Paeān: factīs modo laurea rāmīs adnuit utque caput vīsa est agitāsse cacūmen.

transferred epithet personification mediam : word picture simile, chiasmus epithet enjambment

The Laurel

•

Laurus nobilis

– evergreen, aromatic

•

Uses

– cooking and ornamental herb

– medicinal (salve for wounds, folk remedy for ear/headaches, high blood pressure, cough, poison ivy/oak and stinging nettle, arthritis)

•

Ancient symbolism

– healing

– prophecy

•

Pythia

– victory

•

Pythian Games

• cf. Baccalaureate, “rest on laurels”

– poet’s calling

• cf. poet laureate

–

Bible: resurrection and eternal life

Credit: Theoi.com

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

The Pythia, Apollo’s priestess at

Delphi, was preeminent among ancient oracles. Celibate for life, she gave prophecies on a single day for nine months of the year.

She sat on the tripod where hallucinogenic vapors may have put her in an altered state. Her utterances came forth in hexameters (the “Pythian meter”).

In this image, the Pythia holds the laurel (symbol of Apollo) in her right hand and stares intently into the phiale dish as she prophecies to

Aegeus.

Attic Red-figure. Themis (Pythia) - Aegeus Consults the Pythia Seated on a Tripod. By the Kodros

Painter, c. 440-430 B.C. Antiken-sammlung, Berlin, Germany. Credit: Ancienthistory.about.com.

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

From Theoi.com:

•

Ovid places the aetion in the Valley of Tempe in Thessaly, which is where the river Peneios flows into the Aegean sea. In the valley was a sacred laurel tree, the fronds of which were used to crown the victors of the Pythian games. The contests were originally musical, but athletic events were added in 585 B.C.

•

In a festival at Delphi, a branch of a sacred laurel tree was fetched from the Thessalian vale of Tempe. This rite would suggest that the Thessalian version of the Daphne myth was the older than the one told by Ovid as an aetion .

•

There was also a Delphic myth about

Daphnis, an oreiad nymph who was Gaia's prophetic priestess at Delphoi before Apollo took control of the oracle.

Valley of Tempe and the Peneus River

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

Mosaic from Antioch, House of Menander; ca. 2 nd - 3 rd century A.D.

Antakya Museum, Antakya, Turkey

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

From Theoi.com:

•

Pausanias, Description of Greece 10. 7. 8 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue

C2nd A.D.) : "The reason why a crown of laurel is the prize for a Pythian victory is in my opinion simply and solely because the prevailing tradition has it that Apollo fell in love with the daughter of Ladon [Daphne].”

•

Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 1. 16 (trans. Conybeare) (Greek biography C1st to 2nd A.D.) : "[In Antiokhos (Antioch) in Asia Minor is] the temple of Apollo Daphnaios, to which the Assyrians attach the legend of Arkadia. For they say that Daphne, the daughter of Ladon, there underwent her metamorphosis, and they have a riving flowing there, the

Ladon, and a laurel tree is worshipped by them which they say was substituted for the maiden.”

•

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 203 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd

A.D.) : "When Apollo was pursuing the virgin Daphne, daughter of the river Peneus, she begged for protection from Terra [Gaia the Earth], who received her, and changed her into a laurel tree. Apollo broke a branch from it and placed it on his head."

The Laurel: Mythic Sources

From Theoi.com:

•

Nonnus, Dionysiaca 33. 210 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.)

: "She told how the knees of that unwedded Nymphe [Daphne] fled swift on the breeze, how she ran once from Phoibos quick as the north wind, how she planted her maiden foot by the flood of a long-winding river, by the quick stream of Orontes, when the Earth (Gaia) opened beside the wide mouth of a marsh and received the hunted girl into her compassionate bosom . . . the god never caught Daphne when she was pursued, Apollo never ravished her . . . and [he] always blamed Gaia (earth) for swallowing the girl before she knew marriage.”

• Nonnus, Dionysiaca 42. 386 ff : "How the daughter of Ladon [Daphne], that celebrated river, hated the works of marriage and the Nymphe became a tree with inspired whispers, she escaped the bed of Phoibos but she crowned his hair with prophetic clusters."

The Laurel: Mythic Interpretations

The myth of Daphne is one that has inspired many interpretations, and Joseph

Campbell offers his take in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. His approach is to view the phenomenon of the hero in various cultures as the “monomyth,” the basis of all great deeds and stories of societies.

On the “call to adventure” of the hero:

“(The) first stage of the mythological journey– which we have designated the “call to adventure”– signifies that destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.”

On the refusal of the call:

“Often in actual life, and not infrequently in the myths and popular tales, we encounter the dull case of the call unanswered; for it is always possible to turn the ear to other interest. Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or “culture,” the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved.”

The Laurel: Mythic Interpretations

On Daphne’s flight from Apollo:

“This is indeed a dull and unrewarding finish. Apollo, the sun, the lord of time and ripeness, no longer pressed his frightening suit, but instead simply named the laurel his favorite tree and ironically recommended its leaves to the fashioners of victory leaves. The girl had retreated to the image of her parent and there found protection…”

Jungian psychoanalysis:

“The literature of psychoanalysis abounds in examples of such desperate fixations.

What they represent is an impotence to put off the infantile ego, with its sphere of emotional relationships and ideals. One is bound in by the walls of childhood; the father and mother stand as threshold guardians, and the timorous soul, fearful of some punishment, fails to make the passage through the door and come to birth in the world without.”

Discussion

•

Reactions?

•

What metamorphoses occur in this tale?

– What is the impetus of these changes?

– How has Ovid prepared us for these metamorphoses before they occur?

– Are they in any way contrary to our expectations?

•

How do Apollo and Daphne react to these transformations?

–

Who is sympathetic? With whom do we identify?

• How does Ovid “paint” this story? What visual cues does he give?

•

How does Ovid directly reference Augustus in this story? How does he indirectly reference him?

–

Are they favorable comparisons? Why or why not?

What do the laurels on the front of Augustus’s house symbolize?

Why was this such an important symbol for him?

Credit: Paul Zanker

The decoration of coins was a practical method of conveying propaganda throughout the empire, and Augustus made frequent use of the laurel as a symbol of victory in his coinage. Coin a shows the House of Augustus, flanked by two laurel trees with the oak wreath above the doors ( aureus from

Rome, 12 B.C.). Coins b and c (both aurei from Spain and Gaul, both 19/18

B.C.) again depict the two laurels , and on coin c , laurels grow on either side of the clipeus virtutis .

Res Gestae Divi Augusti

In consulatu sexto et septimo, postquam bella civilia exstinxeram, per consensum universorum potitus rerum omnium, rem publicam ex meā potestate in senatūs populique Romani arbitrium transtuli. Quo pro merito meo senatūs consulto

Augustus appellatus sum et laureis postes aedium mearum vestiti publice coronaque civica super ianuam meam fixa est et clupeus aureus in curia Iulia positus, quem mihi senatum populumque Romanum dare virtutis clementiaeque et iustitiae et pietatis causa testatum est per eius clupei inscriptionem. Post id tempus auctoritate omnibus praestiti, potestatis autem nihilo amplius habui quam ceteri qui mihi quoque in magistratu conlegae fuerunt.

--Augustus, Res Gestae 34

In my sixth and seventh consulships, when I had extinguished the flames of civil war, after receiving by universal consent the absolute control of affairs, I transferred the republic from my own control to the will of the senate and the Roman people. For this service I was named Augustus by decree of the Senate.

The doorposts of my house were officially decked out with young laurel trees, the corona civica was placed over the door, and in the Curia Iulia was displayed the golden shield ( clipeus virtutis ), which the

Senate and the people granted me on account of my bravery, clemency, justice, and piety ( virtus, clementia, iustitia, pietas ), as is inscribed on the shield itself. After that time I took precedence of all in rank, but of power I possessed no more than those who were my colleagues in any magistracy.

Clipeus Virtutis

Replica of the honorary shield of Augustus, awarded to him by the

Senate in 27 B.C. and displayed in the Curia;

Museum of Arles.

Credit: Livius.org

Mausoleum of

Augustus

Credit: The Online

Database of Ancient Art

Click here for more information about the reconstruction of the mausoleum.

Another reconstruction:

Upper right: The Mausoleum of

Augustus today. Lower right:

Google Earth view of the mausoleum. Below: The Ara

Pacis, located in the mausoleum complex with the Horologium.

Credit:

LacusCurtius.org

Ovid’s

Nachleben

(“Survival” or “afterlife”)

In the final lines of the Metamorphoses , Ovid points to the future of his work:

Iamque opus exegi, quod nec Iovis ira nec ignis nec poterit ferrum nec edax abolere vetustas. cum volet, illa dies, quae nil nisi corporis huius ius habet, incerti spatium mihi finiat aevi: parte tamen meliore mei super alta perennis 875 astra ferar, nomenque erit indelebile nostrum, quaque patet domitis Romana potentia terris, ore legar populi, perque omnia saecula fama, siquid habent veri vatum praesagia, vivam.

And now the work is done, that Jupiter’s anger, fire or sword cannot erase, nor the gnawing tooth of time. Let that day, that only has power over my body, end, when it will, my uncertain span of years: yet the best part of me will be borne, immortal, beyond the distant stars. Wherever Rome’s influence extends, over the lands it has civilised, I will be spoken, on people’s lips: and, famous through all the ages, if there is truth in poet’s prophecies, – vivam - I shall live. ( Trans . A.S. Kline)

Ovid’s

Nachleben

Metamorphosing the Metamorphoses

•

Manuscript tradition

•

Ancient admirers and imitators

•

Middle Ages

– new cultural preeminence in 12 th – 13 th centuries (“

Aetas Ovidiana

”)

– courtly love; Chretien de Troyes

– moralizing trend (Ovide Moralise)

–

Chaucer, Boccaccio, Dante

• Renaissance

–

Arthur Golding translation

–

Milton, Spenser, Shakespeare

–

Opera ( Dafne , 1598); painting and sculpture

•

Modern period

•

17 th - 18 th centuries: Dryden , Pope, Goethe, Keats

•

Romanticism: low point in Ovidian studies

•

20 th century: James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Franz Kafka; psychology

•

Contemporary revival

Credits: goodreads.com

WATCH A TRAILER

(click here)

Zimmerman finished the play in 1998, and it opened on Broadway in 2002

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

Breugel, ca. 1558

Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Belgium

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” --William Carlos Williams

According to Brueghel when Icarus fell it was spring a farmer was ploughing his field the whole pageantry of the year was awake tingling with itself sweating in the sun that melted the wings' wax unsignificantly off the coast there was a splash quite unnoticed this was Icarus drowning

“Musee des Beaux Arts” --W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters: how well they understood Its human position: how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along; How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting For the miraculous birth, there always must be Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating On a pond at the edge of the wood: They never forgot That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

“The Tree” – Ezra Pound, 1921-24

I stood still and was a tree amid the wood, Knowing the truth of things unseen before; Of Daphne and the laurel bow And that god-feasting couple old that grew elm-oak amid the wold. 'Twas not until the gods had been Kindly entreated, and been brought within Unto the hearth of their heart's home That they might do this wonder thing; Nathless I have been a tree amid the wood And many a new thing understood That was rank folly to my head before.

“Where I Live in the Honorable House of the Laurel Tree”

I live in my wooden legs and O my green green hands.

– Anne Sexton, 1960

Too late to wish that I had not run from you, Apollo, blood moves still in my bark bound veins,

I, who ran nymph foot to root in flight, have only this late desire to arm the trees I lie within. The measure that I have lost silks my pulse. Each century, the trickeries of need pain me everywhere.

Frost taps my skin and I stay glossed in honor, for you are gone in time. The air rings for you, for that astonishing rite of my breathing tent undone with your light.

I only know how this untimely lust has tossed flesh at the wind forever and moved my fears toward the intimate Rome of the myth we crossed.

I am a fist of my unease as I spill toward the stars in the empty years.

I build the air with the crown of honor; it keys my out of time and luckless appetite.

You gave me honor too soon, Apollo.

There is no one left who understands how I wait here in my wooden legs and O my green green hands.

“Ovid in the Third Reich” -- Geoffrey Hill, 1968

non peccat, quaecumque potest peccasse negare, solaque famosam culpa professa facit.

-Amores , III, xiv

I love my work and my children. God

Is distant, difficult. Things happen.

Too near the ancient troughs of blood

Innocence is no earthly weapon.

I have learned one thing: not to look down

So much upon the damned. They, in their sphere,

Harmonize strangely with the divine

Love. I, in mine, celebrate the love-choir .

“Daphne” – Alicia E. Stallings, 1999

Poet, Singer, Necromancer—

I cease to run. I halt you here,

Pursuer, with an answer:

Do what you will.

What blood you've set to music I

Can change to chlorophyll,

And root myself, and with my toes

Wind to subterranean streams.

Through solid rock my strength now grows.

Such now am I, I cease to eat,

But feed on flashes from your eyes;

Light, to my new cells, is meat.

Find then, when you seize my arm

That xylem thickens in my skin

And there are splinters in my charm.

I may give in; I do not lose.

Your hot stare cannot stop my shivering,

With delight, if I so choose.

Sources

Unless otherwise specified, all images are from Wikimedia Commons.

• A.S. Kline, “Ovid’s

Metamorphoses

”: http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm#askline

•

Mythology and images: www.theoi.com

•

Res Gestae text and translation: www.LacusCurtius.org

•

Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988.

•

Poems by William Carlos Williams and W.H. Auden: http://english.emory.edu/classes/paintings&poems/auden.html

•

Poem by Geoffrey Rich: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/178125

•

Poems by Ezra Pound and Anne Sexton: www.poemhunter.com

•

Poem by A.E. Stallings: www.poemtree.com