Parties and How to Keep Track of Them: Supreme Court

advertisement

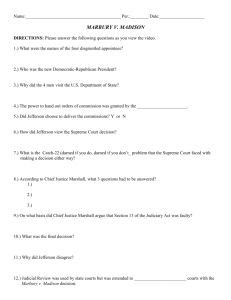

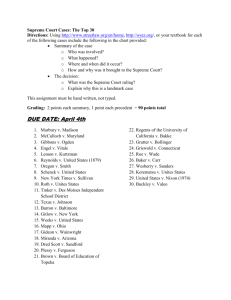

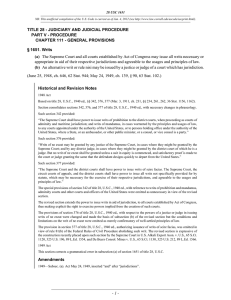

Briefing Supreme Court Cases Parties and How to Keep Track of Them: Trial Courts • Plaintiffs – Sue defendants in civil court. • Government – Prosecutes defendants in criminal cases. Parties and How to Keep Track of Them: Supreme Court • Cases coming to the Court on a writ of certiorari: • Petitioner is the party asking the Court to overturn a lower court decision. • Respondent is the party who wins in the lower court and responds to the petition in the Supreme Court. Parties and How to Keep Track of Them: Supreme Court • Cases that come to the Court on appeal. • Appellant: Person/party who formally appeals to the Court (almost never happens). • Appellee: Person/party who responds to the appeal. Parties and How to Keep Track of Them: Supreme Court • The petitioner/appellant name always appears first in a case, and the order can change. • Trial: Johnson v. Udani (Johnson wins). • Appeal: Udani v. Johnson (because Udani lost at trial court). What Goes into a Brief: Title and Citation • Title: Shows who is opposing whom. • Person/party who initiates legal action always appears first. • Citation: Shows how to locate the case in a legal reporter. • U.S. Reports Citation: 484 U.S. 275 (volume No. U.S. page No.) What Goes into a Brief: Facts of the Case • A general overview of the RELEVANT case facts. • A one-sentence description of the nature of the case, to serve as an introduction. • A statement of the relevant law—that is, what statute of constitutional provision is at issue (this may be abstract). Facts (continued) • A summary of the complaint (in a civil case) or the indictment (in a criminal case). • This includes an explanation of who did what to whom and the arguments raised by each side. • A summary of actions taken by the lower courts, for example: defendant convicted; conviction upheld by appellate court; Supreme Court granted certiorari. What Goes into a Brief: Legal Issues • What exact question does the Court want to answer in this case? • Cases often have multiple issues, and your job is to figure out what issue is the main one presented in the excerpt you have read. • If a constitutional provision/statute is involved, include it in the question if possible. What Goes into a Brief: Holding • How does the Court answer? It is often easiest to write the legal question as “Yes/No” so that the answer is easy to determine. • What is the vote in the case? What Goes into a Brief: Reasoning • What is the logic behind the decisions (cite relevant arguments, precedents, etc.). • Follow the order of the opinion, and number your arguments point by point. • Caution: Reasoning v. obiter dicta (“said by the way”). Marbury is the quintessential example! What Goes into a Brief: Separate Opinions • List relevant arguments from additional opinions (in a sentence or two). • Knowing how each justice voted in this case will help you understand how they may vote in future cases. What Goes into a Brief: Analysis • What is important about this decision? • Is the argument sound? How does it fit with previous decisions of the Court? • What are the possible implications for this decision? • If the case is narrowly decided, what are the differences noted by the dissenters and what bearing might they have on future cases? Writing Briefs: A Cautionary Note • Don’t brief the case until you have read it through at least once. • Don’t think that because you have found the judge’s best purple prose you have necessarily extracted the essence of the decision. • Look for unarticulated premises, logical fallacies, manipulation of the factual record, or distortions of precedent. Example: Marbury v. Madison (1803) • Relevant Case Facts: After the election of 1800, President Adams and the Federalist-controlled Congress created six new circuit courts and several new district courts. They then tried to staff these courts during the last six months of Adams’s term. As part of the Organic Act of 1801Adams was also allowed to appoint forty-two justices of the peace in the District of Columbia. Several of the commissions were not delivered by Secretary of State John Marshall—including the appointment for William Marbury. When Jefferson came into office he told James Madison, the new secretary of state, not to deliver these commissions. As a result Marbury appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, asking the justices for a writ of mandamus ordering Madison to deliver the commissions. The lawsuit was based on Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which gave the Court the power to issue such writs. Legal Question: • Does the Supreme Court have the power to issue a writ of mandamus in order for an appointed judge to secure his commission? Holding: • No. By a vote of 4 to 0 the Court ruled that such power is not in the Constitution. Legal Reasoning: • Marbury has the right to his commission because the only requirement is the presidential seal. And, because President Adams affixed his seal to Marbury’s appointment he is entitled to it. For the current administration to deny the commission would violate his rights. • Marbury brought this case to the Court under its original jurisdiction, citing Article 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which added writs of mandamus to the Court’s original jurisdiction. Original jurisdiction, however, is set by Article III of the Constitution, and it does not include writs of mandamus. Any law contrary to the Constitution is void, and because this act is contrary to Article III it is void and unconstitutional. Marbury is not entitled to his commission. • Marshall asserts the Court’s power of judicial review—–the power to declare as void laws contrary to the Constitution. Specifically he argued: • • • • The Court has the duty to say what is law. The Court decides whether laws violate the Constitution. The Court has this power over all laws passed under the Constitution. In short, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what is the law.” Example: Ex parte McCardle (1869) • Relevant Case Facts: After the Civil War the Republican Congress instituted Reconstruction laws in the South. Specifically, it placed the South under military rule. McCardle wrote editorials opposing these measures and urged resistance against them. He was arrested for publishing “incendiary and libelous articles” and was held for trial before a military tribunal. McCardle argued that he was a citizen and not a member of militia and was therefore being illegally held. He filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus as allowed under Congressional Act of 1867. When this effort failed, he turned to the Supreme Court for help. Before the Court could hear the case, Congress repealed the Habeas Corpus Act, removing the Supreme Court’s authority to hear such cases. Legal Question: • Can the Supreme Court hear a petition for a writ of habeas corpus when Congress has taken away such authority? Holding: • No. By a vote of 8 to 0 the Court said it could not decide such cases. Legal Reasoning: • • • The Judiciary Act of 1789 established judicial courts in the United States, and set jurisdiction for these courts. Congress has expressly taken away the Court’s power to decide cases involving writs of habeas corpus. Without jurisdiction, this Court cannot proceed in this matter. The Court’s only function in instances such as this one is to declare that no jurisdiction exists and to dismiss the case. GLOSSARY TERMS • Writ of mandamus – “We • command.” a writ issued by a court commanding a public official to carry out a particular act or duty. Ex Parte – A hearing in which only one party to a dispute is present.