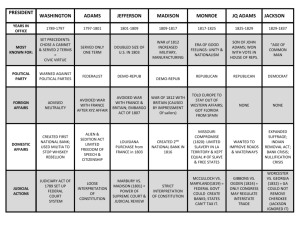

Party Affiliation

advertisement

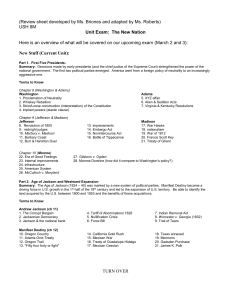

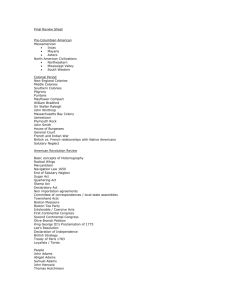

Biography: President James Madison 1809-1817 Party Affiliation Believing that the Articles of Confederation rendered the new republic subject to foreign attack and domestic turmoil, James Madison helped set the wheels in motion for a national convention to draft the young nation's Constitution. Madison led the Virginia delegation to the Philadelphia meeting, which began on May 14, 1787, and supported the cry for General Washington to chair the meeting. Madison's "Virginia Plan" became the blueprint for the constitution that finally emerged, eventually earning him the revered title, "Father of the Constitution." Having fathered the document, Madison worked hard to ensure its ratification. Along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, he published the Federalist Papers, a series of articles arguing for a strong central government subject to an extensive system of checks and balances. Under Thomas Jefferson, Madison served as secretary of state, supporting the Louisiana Purchase and the embargo against Britain and France. Indeed, Madison shaped foreign policy during Jefferson's administration, emerging from behind the scenes in 1808 to succeed him as the fourth President of the United States. It was not at all clear that Madison would carry the day. Jefferson's embargo of all trade with Britain and France had devastated the nation. New England states spoke of open secession from the Union. The Federalists, convinced they would ride national outrage to victory, renominated their 1804 contender, Charles C. Pinckney of South Carolina. Meanwhile, George Clinton, who had agreed to run as Madison's vice president, also consented to run for President! Madison swamped the opposition, winning 122 votes to Pinckney's 44. His reelection was also dramatic. Madison's nomination for a second term came just fifteen days prior to his war message to Congress, listing American grievances against Britain. Congress voted the United States into the War of 1812, largely guaranteeing Madison's reelection. Supreme Court Decisions See Marbury vs. Madison (John Adams reading) Domestic Policy During the James Madison presidency, domestic affairs took a backseat to foreign affairs, as would be expected of a nation at war. The President made this point clear in his public addresses. For example, Madison's first inauguration speech stressed his commitment to neutrality in the French-English conflict while insisting that U.S. neutrality be respected without conditions by the warring parties. His second speech, delivered on March 13, 1813, ten months into the war, accused the British of arming frontier "savages" in vicious acts of war upon the American citizenry. Indeed, almost everything else seemed trivial in comparison to the conflict with Britain. Among the domestic issues that did stand somewhat apart from the war itself was the struggle over the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States, whose charter was scheduled to terminate in 1812. The move to re-charter the Bank met stiff opposition from three sources: "old" Republicans who viewed the Bank as unconstitutional and a stronghold of Hamiltonian power, anti-British Republicans who objected to the substantial holdings of Bank stock by Britons, and state banking interests opposed to the U.S. Bank's power to control the nation's financial business. When the anti-Bank forces killed the re-charter drive, the U.S. confronted the British without the means to support war loans or to easily obtain government credit. In 1816, with Madison's support, the Second Bank was chartered with a twenty-year term. Madison's critics claimed that his support for the Bank revealed his pro-Federalist sympathies. Foreign Policy For Madison and the War Hawks, the declaration of war against Great Britain amounted to a second war of independence for the new Republic. It also provided the opportunity to seize Canada, drive the Spanish from west Florida, put down the Indian uprising in the Northwest, and secure maritime independence. In the preparations for battle, it became clear that most of the War Hawks wanted a land invasion of Canada above all else. Accordingly, the United States moved quickly to mount an offensive against Canada. Unfortunately, the move ended in disaster for American forces. Things went better for the Americans in the spring of 1813. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory over the British fleet on the southwestern tip of Lake Erie, following the sacking of the Canadian capital city of York (present-day Toronto), enabled the United States to send a force commanded by William Henry Harrison, who would become the ninth President of the United States, against the Native American leader, Tecumseh, at the Battle of the Thames River in western Ontario. A vengeful force of Kentucky militia beat the Indians badly. The following spring, General Andrew Jackson's Tennessee militia, aided by Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee allies, slaughtered what was left of the late Tecumseh's forces at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, deep in the Mississippi Territory (present-day Alabama). Events swung back against the Americans in late spring of 1814 as the British, who had now defeated Napoleon, went on the offensive. British ships raided American ports from Georgia to Maine, occupying half the district of Maine in the process. They also launched an invasion down the Champlain Valley that was repelled after an American naval victory on Lake Champlain in September 1814. British forces were more successful in targeting the nation's capital in Washington, D.C. The seat of American government fell, with British troops torching the White House and most other federal buildings in retaliation for the burning of the Canadian Parliament buildings in York. Their offensive stalled in Baltimore, however, as they were unable to blast their way past Fort McHenry. It was this battle, in fact, that inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner," which became the American national anthem in the 1930s. Next, the British turned their attention to New Orleans, hoping to use the city as a bargaining chip in the coming peace negotiations. A massive British Army of 6,000 soldiers moved against the city, which was protected by Andrew Jackson's diverse command of 4,000 regular soldiers, Kentucky and Tennessee militia, and New Orleans citizens, including many free blacks and slaves and nearly 1,000 French pirates. When the British charged across an open field a few miles below the city on January 8, the entrenched Americans laid down such heavy fire that 2,000 Redcoats fell dead within minutes. Those who survived the first blast simply threw down their weapons and withdrew. Only seventy Americans died. Unbeknownst to either army, the battle came two weeks after a peace treaty had been signed in Ghent, Belgium. Although Madison fared poorly during the war, the victories against Tecumseh and at New Orleans lifted American spirits and returned Madison to a high point of public respect. If nothing else, the war swelled national pride, broke the Indian threat in the Northwest, and reaped tremendous political benefits for those lucky enough to have fought and survived. General Jackson, moreover, emerged as a genuine war hero, equal in public esteem to George Washington. The 2,200 dead Americans undoubtedly left behind families proud of the men who had won the Second American Revolution. Biography: President Thomas Jefferson 1801-1809 Party Affiliation Sharp political conflict developed, and two separate parties, the Federalists and the DemocraticRepublicans, began to form. Jefferson gradually assumed leadership of the Republicans, who sympathized with the revolutionary cause in France. Attacking Federalist policies, he opposed a strong centralized Government and championed the rights of states. such as Adams and Washington and more extreme Federalists like Hamilton. In the presidential election of 1800, Hamiltonian Federalists refused to back Adams, clearing the way for the Republican candidates Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr to tie for first place with 73 electoral votes each. After a long and contentious debate, the House of Representatives selected Jefferson to serve as the third U.S. president, with Burr as his vice president. The election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800 was a landmark of world history, the first peacetime transfer of power from one party to another in a modern republic. Delivering his inaugural address on March 4, 1801, Jefferson spoke to the fundamental commonalities uniting all Americans despite their partisan differences. "Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle," he stated. "We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists." The Jeffersonian Republicans placed their faith in the virtues of an agrarian democracy. They believed that the greatest threat to liberty was posed by a tyrannical central government and that power in the hands of the common people was preferred. Those natural democratic instincts required sharpening, however, by education. In foreign affairs, the Jeffersonian-Republicans favored France over Britain. Jefferson lauded the French Revolution, which claimed the American Revolution as its model, but decried its bloody excesses. The Jeffersonian-Republicans opposed the Jay's Treaty (1795) as excessively pro-British. The Jeffersonians began using the name Democratic-Republicans in 1796, and would later shorten it to Republicans. During the time of Andrew Jackson they became the Democratic Party. Supreme Court Decision See Marbury vs. Madison (John Adams reading) Domestic Policy When Jefferson learned that Spain had secretly ceded Louisiana to France in 1800, he instructed his ministers to negotiate the purchase of the port of New Orleans and possibly West Florida. Jefferson strategically made this move in order to insure that American farmers in the Ohio River Valley had access to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River—the river was a key to the farmers' economic well-being, as they needed a vent for their surplus grain and meat. Even before the French took over Louisiana, the Spaniards had closed the Mississippi River in 1802. While Jefferson was known to be partial to the French, having the Emperor Napoleon's driving interests for world domination next door was not an attractive prospect; thus, Jefferson acted swiftly. To his surprise, Napoleon, needing funds to finance a new European war with England, offered to sell Jefferson most of the land from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. His price of $15 million amounted to approximately four cents per acre for 828,000 square miles, doubling the size of the nation. Although Jefferson understood that the U.S. Constitution said nothing about the purchase of foreign territory, he set aside his strict constructionist ideals to make the deal—Congress approved the purchase five months after the fact. Jefferson then outfitted a twenty-five man expedition to explore the new lands. Led by his secretary, Meriwether Lewis, and Army Captain William Clark, these adventurers took two and one-half years to cover 8,000 miles. They traveled up the Missouri River, across the Continental Divide, and down the Columbia River to the Pacific before retracing their steps to St. Louis. The expedition is considered one of the great exploratory quests in human history. Foreign Policy Several weeks after buying Louisiana, Napoleon declared war on Great Britain. At first, the European fighting benefited the United States since Americans functioned as the merchants carrying supplies to the warring powers. Consequently, between 1803 and 1807, total U.S. exports jumped from $66.5 million to $102.2 million. This service provided by American ships often involved re-exporting, meaning European and colonial goods were picked up by American ships for transport to U.S. ports where they were reloaded onto other U.S. ships for export to Europe. During the same four-year period, reexports quadrupled, rising from $13.5 million to $58.4 million. Then, the bottom fell out of the trade industry as England and France each independently outlawed virtually all American commerce with their opponent. The British navy also began seizing American ships with cargoes bound for Europe and impressing American sailors into the Royal Navy. The problem partly stemmed from the practice of British sailors jumping ship to join U.S. merchant vessels. Thousands of such deserters were considered fair prey by the British navy, which also routinely impressed American citizens on the pretext that they were British deserters, many of whom were in fact just that. Tensions mounted, and in the summer of 1807, the British warship Leopard fired on the American naval frigate Chesapeake, killing three Americans, when the ship refused boarding orders. Cries for war erupted throughout the nation. Jefferson banned all British ships from U.S. ports, ordered state governors to prepare to call up 100,000 militiamen, and suspended trade with all of Europe. He reasoned that U.S. farm products were crucial to France and England and that a complete embargo would bring them to respect U.S. neutrality. By spring 1808, however, the Embargo Act that was passed by Congress in December 1807 had devastated the American economy. American exports plummeted from $108 million to $22 million. Economic desperation settled upon the mercantile Northeast. Finally, Jefferson backed off in the last months of his administration, and Congress replaced the Embargo Act with the Non-Intercourse Act, which banned trade with England and France but allowed it with all other countries. Eventually, the trade war would propel America into a fighting war with England during the administration of Jefferson's successor, James Madison. Biography: President James Monroe 1817-1825 Party Affiliation James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States Monroe and the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States. As an anti-federalist delegate to the Virginia convention that considered ratification of the United States Constitution, Monroe opposed ratification, claiming it gave too much power to the central government. He took an active part in the new government, and in 1790 he was elected to the Senate of the first United States Congress, where he joined the Jeffersonians. Monroe largely ignored old party lines in making appointments to lower posts, which reduced political tensions and enabled the "Era of Good Feelings", which lasted through his administration. He made two long national tours in 1817 to build national trust. Frequent stops on these tours allowed innumerable ceremonies of welcome and expressions of good will. The Federalist Party continued to fade away during his administration; it maintained its vitality and organizational integrity in Delaware and a few localities, but lacked influence in national politics. Lacking serious opposition, the Democratic-Republican Party's Congressional caucus stopped meeting, and for practical purposes the Democratic-Republican Party stopped operating. Supreme Court Decisions McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) - Landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States. The state of Maryland had attempted to impede operation of a branch of the Second Bank of the United States by imposing a tax on all notes of banks not chartered in Maryland. Though the law, by its language, was generally applicable to all banks not chartered in Maryland, the Second Bank of the United States was the only out-of-state bank then existing in Maryland, and the law was recognized in the court's opinion as having specifically targeted the Bank of the U.S. The Court invoked the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution, which allowed the Federal government to pass laws not expressly provided for in the Constitution's list of express powers, provided those laws are in useful furtherance of the express powers of Congress under the Constitution. This case established two important principles in constitutional law. First, the Constitution grants to Congress implied powers for implementing the Constitution's express powers, in order to create a functional national government. Second, state action may not impede valid constitutional exercises of power by the Federal government. Domestic Policy Monroe's popularity was undiminished even when following difficult nationalist policies as the country's commitment to nationalism was starting to show serious fractures. The Panic of 1819 caused a painful economic depression. The application for statehood in 1819 by the Missouri Territory as a slave state failed. An amended bill for gradually eliminating slavery in Missouri precipitated two years of bitter debate in Congress. The Missouri Compromise bill resolved the struggle, pairing Missouri as a slave state with Maine, a free state, and barring slavery north of latitude 36/30' N forever. The Missouri Compromise lasted until 1857, and would remain a serious issue between north and south. Congress demanded high subsidies for internal improvements, such as for the improvement of the Cumberland Road, during Monroe's presidency. Monroe vetoed the Cumberland Road Bill, which provided for yearly improvements to the road, because he believed it to be unconstitutional for the government to have such a large hand in what was essentially a civics bill deserving of attention on a state by state basis. Monroe sparked a constitutional controversy when, in 1817, he sent General Andrew Jackson to move against Spanish Florida to pursue hostile Seminole Indians and punish the Spanish for aiding them. Monroe believed that the Indians must progress from the hunting stage to become an agricultural people, noting, "A hunter or savage state requires a greater extent of territory to sustain it than is compatible with progress and just claims of civilized life." Foreign Policy Monroe formally announced in his message to Congress on December 2, 1823, what was later called the Monroe Doctrine. He proclaimed that the Americas should be free from future European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. It further stated the United States' intention to stay neutral in European wars and wars between European powers and their colonies, but to consider new colonies or interference with independent countries in the Americas as hostile acts toward the United States. Although it is Monroe's most famous contribution to history, the speech was written by John Quincy Adams, who designed the doctrine in cooperation with Britain. Monroe and Adams realized that American recognition would not protect the new countries against military intervention. The Doctrine stated that not only must Latin America be left alone, but also Russia must not encroach southward on the Pacific coast. "...the American continents," he stated, "by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European Power." The result was a system of American isolationism. The Monroe Doctrine held that the United States considered the Western Hemisphere as no longer a place for European colonization; that any future effort to gain further political control in the hemisphere or to violate the independence of existing states would be treated as an act of hostility; and finally that there existed two different and incompatible political systems in the world. The United States, therefore, promised to refrain from intervention in European affairs and demanded Europe to abstain from interfering with American matters. Monroe also worked on a treaty with Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the United States and supported the founding of colonies in Africa for free African Americans that would eventually form the nation of Liberia, whose capital, Monrovia, is named in his honor. Biography: President Andrew Jackson 1829-1837 Party Affiliation Jackson's name has been associated with the spread of democracy in terms of the passing of political power from established elites to ordinary voters based in political parties. "The Age of Jackson" shaped the national agenda and American politics. Jackson's philosophy as President followed much in the same line as Thomas Jefferson, advocating Republican values held by the Revolutionary War generation. Jackson's presidency held a high moralistic tone; having as a planter himself agrarian sympathies, a limited view of states' rights and the federal government. Jackson feared that money and business interests would corrupt republican values. When South Carolina opposed the tariff law he took a strong line in favor of nationalism and against secession. Jackson was the first President to invite the public to attend the White House ball honoring his first inauguration. Many poor people came to the inaugural ball in their homemade clothes. The crowd became so large that Jackson's guards could not keep them out of the White House, which became so crowded with people that dishes and decorative pieces inside were eventually broken. Some people stood on good chairs in muddied boots just to get a look at the President. The crowd had become so wild that the attendants poured punch in tubs and put it on the White House lawn to lure people outside. Jackson's raucous populism earned him the nickname "King Mob". Jackson believed that the president's authority was derived from the people and the presidential office was above party politics. Instead of choosing party favorites, Jackson chose "plain, businessmen" whom he intended to control. Supreme Court Decision Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but the Supreme Court did not hear the case on its merits. It ruled that it had no original jurisdiction in the matter, as the Cherokee was a dependent nation, with a relationship to the United States like that of a "ward to its guardian." Worcester v. Georgia (1832). Chief Justice John Marshall laid out the relationship between the Indian Nations and the United States. The court ruled that the individual states had no authority in American Indian affairs. Marshall's language in Worcester may have been motivated by his regret that his earlier opinions in Fletcher and Johnson had been used as a justification for Georgia's actions. In a popular quotation, President Andrew Jackson reportedly responded: "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" Because Jackson proceeded with Cherokee removal, Worcester did little more for indigenous rights than Johnson v. M'Intosh or Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. Domestic Policy When Jackson became President, he implemented the theory of rotation in office for political appointments. Many of the individuals in government offices were holdovers from the Presidency of George Washington, whom Jackson thought were corrupt. He noted, "In a country where offices are created solely for the benefit of the people no one man has any more intrinsic right to official station than another." He believed that rotation in office would prevent the development of a corrupt bureaucracy. Another notable crisis during Jackson's period of office was the "Nullification Crisis", or "secession crisis", of 1828 – 1832, which merged issues of sectional strife with disagreements over tariffs. Southern politicians argued that tariffs benefited northern industrialists at the expense of southern farmers. The issue came to a head when Vice President Calhoun supported the claim of his home state, South Carolina, that it had the right to "nullify"—declare void—the tariff legislation of 1828, and more generally the right of a state to nullify any Federal laws that went against its interests. Although Jackson sympathized with the South in the tariff debate, he also vigorously supported a strong union, with effective powers for the central government. Jackson asked Congress to pass a "Force Bill" explicitly authorizing the use of military force to enforce the tariff. The Force Bill and Compromise Tariff passed on March 1, 1833, and Jackson signed both. The South Carolina Convention then met and rescinded its nullification ordinance. On May 1, 1833, Jackson wrote, "the tariff was only the pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question." The Second Bank of the United States was authorized for a 20-year period during James Madison's tenure in 1816. On July 3, 1832 Congress passed the bank's recharter bill to be quickly vetoed by the president. In Jackson's veto message, he conceded that a national bank may be "convenient", it is "subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people." He went on to call the bank a "monopoly" that hindered the common man, whom he strived to represent as president. Moreover, Jackson thought America should be an "agricultural republic", and that the bank hindered that notion, as it favored northeastern states over southern and western ones, and that it "improved the fortunes of commercial and industrial businesses at the expense of farmers and laborers." Foreign Policy Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Jackson's presidency was his Indian policy. Jackson was a major advocate of a policy known as Indian removal. Jackson had been negotiating and implementing treaties and removal policies with Indian leaders for years before his election as president. Many tribes and portions of tribes had been removed to Arkansas Territory and further west of the Mississippi River with different degrees of acquiescence on the part of the Indians. Further, many white Americans advocated total extermination of the "savages", particularly those who had experienced frontier wars. Violence, both on the part of the white settlers and the Indians, had been increasing in recent decades as white settlers were pushing further west. Before his election as president, Jackson had been involved with the issue of Indian removal. The relocation of the Indians to west of the Mississippi River had been a major part of his political agenda in both the 1824 and 1828 presidential elections. In 1830, congress passed the Indian Removal Act, and Jackson signed it into law. The Act authorized the President to negotiate treaties to buy tribal lands in the east in exchange for lands further west, outside of existing U.S. state borders. Biography: President John Adams 1797-1801 Party Affiliation The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government that favored industry, landowners, banking interests, merchants, and close ties with England. Opposed to them were the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, who advocated limited powers for the federal government. Adams's Federalist leanings and high visibility as vice president positioned him as the leading contender for President in 1796. In the early days of the American electoral process, the candidate receiving the second-largest vote in the electoral college became vice president. This is how Thomas Jefferson, who opposed Adams in the election, came to serve as Adams's vice president in 1797. Adams won the election principally because he identified himself with Washington's administration and because he was able to win two electoral ballots from normally secure Jeffersonian states. In 1800, Adams faced a much tougher battle for reelection, as the differences between the Federalists and the Republicans intensified—by that time, the terms "Democratic-Republican" and "Republican" were used interchangeably. The Supreme Court Marbury v. Madison (1803) Facts of the Case The case began on March 2, 1801, when an obscure Federalist, William Marbury, was designated as a justice of the peace in the District of Columbia. Marbury and several others were appointed to government posts created by Congress in the last days of John Adams's presidency, but these last-minute appointments were never fully finalized. The disgruntled appointees invoked an act of Congress and sued for their jobs in the Supreme Court. (Justices William Cushing and Alfred Moore did not participate.) Question Is Marbury entitled to his appointment? Is his lawsuit the correct way to get it? And, is the Supreme Court the place for Marbury to get the relief he requests? Conclusion Decision: 4 votes for Madison, 0 vote(s) against Legal provision: Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 Yes; yes; and it depends. The justices held, through Marshall's forceful argument, that on the last issue the Constitution was "the fundamental and paramount law of the nation" and that "an act of the legislature repugnant to the constitution is void." In other words, when the Constitution--the nation's highest law--conflicts with an act of the legislature, that act is invalid. This case establishes the Supreme Court's power of judicial review. Domestic Policy President Adams's style was largely to leave domestic matters to Congress and to control foreign policy himself. Not only did the Constitution vest the President with responsibility for foreign policy but perhaps no other American had as much diplomatic experience as Adams. As a result of his outlook, much of his domestic policy was intertwined with his foreign policy, for diplomatic issues often sparked a domestic reaction that consumed the the nation. On the heels of the XYZ Affair (see Foreign Policy section), there were many negative sentiments toward the French. Sensing this mood in the citizenry and identifying an opportunity to crush the pro-French Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson, the Federalist-dominated Congress drafted and passed the Alien and Sedition Acts during the spring and summer of 1798. Supposedly created as a means of preventing the aiding and abetting of France within the United States and of obstructing American foreign policy, the laws in actuality had domestic political overtones. Three of the laws were aimed at immigrants, most of whom tended to vote for Democratic-Republican candidates. The Naturalization Act lengthened the residency period required for citizenship from five to fourteen years. The Alien Act, the only one of the four acts to pass with bipartisan support, allowed for the detention of enemy aliens in time of war without trial or counsel. The Alien Enemies Act empowered the President to deport aliens whom he deemed dangerous to the nation's security. The fourth law, the Sedition Act, outlawed conspiracy to prevent the enforcement of federal laws and punished subversive speech— with fines and imprisonment. There were fifteen indictments and ten convictions under the Sedition Act during the final year and a half of Adams's administration. No aliens were deported or arrested although hundreds of alien immigrants fled the country in 1798 and 1799. In response to the Federalists' use of federal power, Democratic-Republicans Thomas Jefferson and James Madison secretly drafted a set of resolutions. These resolutions were introduced into the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures in the fall of 1798. Jefferson and Madison argued that since the Constitution was created by a compact among the states, the people, speaking through their state legislatures, had the authority to judge the legitimacy of federal actions. Hence, they pronounced the Alien and Sedition Acts null and void. Although no other states formally supported the resolutions, they rallied Democratic-Republican opinion in the nation. Most importantly, they placed the Jeffersonian Republicans within the revolutionary tradition of resistance to tyranny. The resolutions also raised the issue of states' rights and the constitutional question of how conflict between the two authorities would be resolved short of secession or war. Foreign Policy Adams's presidency was consumed with problems that arose from the French Revolution, which had also been true for his predecessor. Initially popular with virtually all Americans, the French Revolution began to arouse concerns among the most conservative in the United States after the excesses that commenced in 1792. Adams had observed the coming of the French Revolution while living in France and Great Britain, and he immediately realized its potential for terror and anarchy. His skepticism was confirmed. Nevertheless, the problems that beset Presidents Washington and Adams arose more from the wars spawned by the French Revolution. War erupted in 1792 when France attempted to export its revolutionary ideas and when several European monarchical nations allied against the French, hoping to eradicate the threat posed by the republican revolutionaries. The great danger for the United States began in the spring of 1793 when Great Britain, the principal source of American trade, joined the coalition against France. Although the Washington administration proclaimed American neutrality, a crisis developed when London sought to prevent U.S. trade with France. Numerous depredations occurred on the high seas, as ships of the Royal Navy seized American ships and cargoes and sought to impress American sailors who had allegedly deserted the British navy. Cries for war with Britain were widespread by 1794. Believing that war would be disastrous, President Washington sent John Jay to London to seek a diplomatic solution. The result was Jay's Treaty, signed in 1794. The treaty improved U.S.-British relations. France, interpreting the treaty as a newly formed alliance between the United States and an old enemy, retaliated by ordering the seizure of American ships carrying British goods. This plunged Adams into a foreign crisis that lasted for the duration of his administration. At first, Adams tried diplomacy by sending three commissioners to Paris to negotiate a settlement. However, Prime Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand of France insulted the American diplomats by first refusing to officially receive them. He then demanded a $250,000 personal bribe and a $10 million loan for his financially strapped country before he would begin peace negotiations. This episode, known as the XYZ affair, sparked a white-hot reaction within the United States. Adams responded by asking Congress to appropriate funds for defensive measures. These included the augmentation of the Navy, improvement of coastal defensives, the creation of a provisional army, and authority for the President to summon up to 80,000 militiamen to active duty. Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts to curb dissent, created the Navy Department, organized the Marine Corps, and cancelled the treaties of alliance and commerce with France that had been negotiated during the War of Independence. Biography: President George Washington 1789-1797 Party Affiliation All through his two terms as president, Washington was dismayed at the growing partisanship within government and the nation. The power bestowed on the federal government by the Constitution made for important decisions, and people joined together to influence those decisions. The formation of political parties at first were influenced more by personality than by issues. “However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” -George Washington, Farewell Address, Sept. 17, 1796 Supreme Court Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) Facts of the Case In 1777, the Executive Council of Georgia authorized the purchase of needed supplies from a South Carolina businessman. After receiving the supplies, Georgia did not deliver payments as promised. After the merchant's death, the executor of his estate, Alexander Chisholm, took the case to court in an attempt to collect from the state. Georgia maintained that it was a sovereign state not subject to the authority of the federal courts. Question Was the state of Georgia subject to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and the federal government? Conclusion In a 4-to-1 decision, the justices held that "the people of the United States" intended to bind the states by the legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the national government. The Court held that supreme or sovereign power was retained by citizens themselves, not by the "artificial person" of the State of Georgia. The Constitution made clear that controversies between individual states and citizens of other states were under the jurisdiction of federal courts. State conduct was subject to judicial review. Domestic Policy As the first president, Washington was astutely aware that his presidency would set a precedent for all that would follow. He carefully attended to the responsibilities and duties of his office, remaining vigilante to not emulate any European royal court. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President," instead of more imposing names that were suggested. At first he declined the $25,000 salary Congress offered the office of the presidency, for he was already wealthy and wanted to protect his image as a selfless public servant. However, Congress persuaded him to accept the compensation to avoid giving the impression that only wealthy men could serve as president. George Washington proved to be an able administrator. He surrounded himself with some of the most capable people in the country, appointing Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State. He delegated authority wisely and consulted regularly with his cabinet listening to their advice before making a decision. Washington established broad-ranging presidential authority, but always with the highest integrity, exercising power with restraint and honesty. In doing so, he set a standard rarely met by his successors, but one that established an ideal by which all are judged. During his first term, Washington adopted a series of measures proposed by Treasury Secretary Hamilton to reduce the nation's debt and place its finances on sound footing. His administration established several peace treaties with Native American tribes and approved a bill establishing the nation's capital in a permanent district along the Potomac River. In 1791, Washington signed a bill authorizing Congress to place a tax on distilled spirits, which stirred protests in rural areas of Pennsylvania. Quickly, the protests turned into a full-scale defiance of federal law known as the Whiskey Rebellion. Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792, summoning local militias from several states to put down the rebellion. Washington personally took command, marching the troops into the areas of rebellion and demonstrating that the federal government would use force, when necessary, to enforce the law. Foreign Policy In foreign affairs, Washington took a cautious approach, realizing that the weak, young nation could not succumb to Europe's political intrigues. In 1793, France and Great Britain were once again at war. At the urging of Alexander Hamilton, Washington disregarded the U.S. alliance with France and pursued a course of neutrality. In 1794, he sent John Jay to Britain to negotiate a treaty (known as the "Jay Treaty") to secure a peace with Britain and clear up some issues held over from the Revolutionary War. The action infuriated Thomas Jefferson, who supported the French and felt that the U.S. needed to honor its treaty obligations. Washington was able to mobilize public support for the treaty, which proved decisive in securing ratification in the Senate. Though controversial, the treaty proved beneficial to the United States by removing British forts along the western frontier, establishing a clear boundary between Canada and the United States, and most importantly, delaying a war with Britain and providing over a decade of prosperous trade and development the fledgling country so desperately needed.