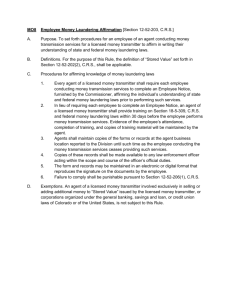

GMSS Money Laundering DA

advertisement