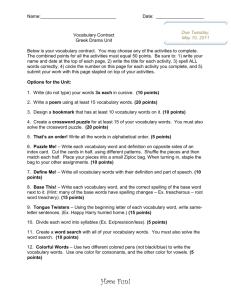

The Least You Should Know About Drama

advertisement

The Least You Should Know About Drama Drama Background Notes Mr. Holley What is Drama? Mystery writer and movie director Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Drama is life with the dull bits cut.” What Makes Drama Unique? Drama has one characteristic peculiar to itself—it is written primarily to be performed, not read. It is a presentation of action a. through actors (the impact is direct and immediate), b. on a stage (a captive audience), and c. before an audience (suggesting a communal experience). Uniqueness of drama continued… Of the four major points of view, the dramatist is limited to only one—the objective or dramatic. The playwright cannot directly comment on the action or the character and cannot directly enter the minds of characters and tell us what is going on there. But there are ways to get around this limitation through the use of 1. soliloquy (a character speaking directly to the audience), 2. chorus (a group on stage commenting on characters and actions), and 3. one character commenting on another. The Power of Drama • Originally, drama had religious purpose. The first theaters were sacred spaces. • Actors must pretend to become their characters. Spectators must pretend to accept stage illusions and identify with the characters (“suspend their belief in reality”). • Drama is a collective experience because the event is shared live between actors and audience. Live Theater Vs. TV and Film Film and TV • Performances are “frozen”—performers are not affected by the reactions of those who are watching. • Editing actors’ performances constructs an “artificial reality.” • Camera’s “eye” controls spectator’s point of view. Live Theater • Actors respond to the reactions of their audience. • Stage actors perform continuously, in “real time”. • Spectator is freer and can choose what to look for. Reading Plays Vs. Reading Fiction Reading Plays • “Economical”—it must tell its story in a short time, with relatively few words and little description. • Little description in a play. You need to use your own imagination to create the scene and character voices. Reading Fiction • Writers can use description, switch easily from scene to scene, and use a narrator to help interpret the action for the reader. Drama Literary Terms • • • • • • • • • • Conflict Character Setting Plot Play Structure Points of View Dialogue Imagery and Symbolism Irony Themes and Ideas Conflict • Conflict is the “skeleton” on which the rest of the play is constructed. • Three types of conflict: 1. Conflict between characters. 2. Conflict between a character and outside forces. 3. Conflict within an individual character. • If the central conflict involves characters who are not evenly matched, audiences tend to side with the “underdog.” (Audience is drawn into caring about the outcome of the conflict) Character • Definition of plot: “character in action.” • Playwright communicates character through the way a character looks, talks, and behaves. • Just as people do in real life, welldrawn stage characters make conflicting choices because they have conflicting—and sometimes hidden—feelings, beliefs, needs, and desires. • Hidden aspects are interesting because the audience gets to see deeper aspects of characters only as the play unfolds. Types of Characters • Flat character—is known by one or two traits • Round character—is complex and many sided • Stock character—is a stereotyped character (i.e. mad scientist; absent minded-professor) • Static character—remains the same from the beginning of the plot to the end • Dynamic character—undergoes permanent change Setting • By setting the play in a specific space and time, the actions of the characters and reactions of the audience are rooted in a specific culture and environment. • Setting affects mood by establishing the “feel” of an environment through the senses: lighting, temperature, sounds, and so on. • Setting affects the psychology of the characters by shaping their backgrounds, attitudes, goals, and emotions. • In modern plays, setting reflects the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters. Plot • Plot is story—the structure of important events that occur during the course of the play. • Good plot:… 1. Has “dramatic unity”—all the actions of the play relate to the central conflict. 2. Follows strict cause and effect. 3. Involves change, action, and movement. • Three kinds of dramatic changes: 1. Physical changes in the characters. 2. Changes in relationships between the characters. 3. Changes in attitude. • “Plot Manipulation”—a good plot should not have any unjustified or unexpected turns or twists; no false leads; no deliberate and misleading information. Play Structure • Exposition: The means by which the playwright communicates various background information to the audience. • Point of attack: The “point of no return” moment in the plot when the chain of events that leads eventually to the climax is set in motion. • Complication: Introduces a new plot element that affects the course of action of the play. • Crisis: The moment (or series of moments) when the conflict comes to a head. • Resolution: The moment or scene at the end of the play which contains the final solution to the problem. Points of View • Omniscient—a story told by the author, using the third person; her/his knowledge, control, and prerogatives are unlimited; authorial subjectivity. • Limited Omniscient—a story in which the author associates with a major or minor character; this character serves as the author’s spokesperson or mouthpiece. • First Person—the author identifies with or disappears in a major or minor character; the story is told using the first person “I” • Objective or Dramatic—the opposite of omniscient; displays authorial objectivity; compared to a roving sound camera. Very little of the past or the future is given; the story is set in the present. Dialogue • Dialogue is the foundation on which • 1. 2. 3. 4. • • drama is built. There are four main functions of dialogue: To allow playwrights to portray characters to the audience. A character’s manner of speaking— accent, rhythm, tone, choice of words— gives important clues about his or her background. How characters speak also reveals their present inner thoughts and feelings. Allows the characters to communicate with each other—”personality in action.” Dialogue doesn’t always rely on words, however. Silence can communicate, too. Subtext is the “real” or “true’ message— when a character says one thing but is really thinking or feeling something else. Imagery and Symbolism Imagery Symbolism • A play is like a poem—it presents a concentrated version of reality, using • In many plays, certain objects on only the most essential parts to stage also take on special meaning, present the story. standing for more than themselves. • An image can be understood on • Real objects (i.e. ring, gun) take on two levels: important symbolic meanings that 1. Denotation: the literal meaning. remind the audience of key ideas or 2. Connotation: all the other ideas that the characters associated with them. are associated with it. • Same images and symbolic objects recur throughout the play, often • Some playwrights use poetic changing meaning as the play grows. language as “word pictures” to expand the scope and meaning of what happens on the stage. • Playwrights use images that draw on the audience’s emotional associations to express more than one idea at a time. Irony • Irony should not be confused with “sarcasm” which is simply language designed to cause pain. • Irony is used to suggest the difference between appearance and reality, between expectation and fulfillment. • Three types of irony: 1. Verbal irony—the opposite is said from what is intended. 2. Dramatic irony—the contrast between what a character says and what the reader knows to be true. 3. Irony of situation—discrepancy between appearance and reality, or between expectation and fulfillment, or between what is and what would seem appropriate. Themes and Ideas • Themes give drama structure and focus. Many themes help audiences recognize universal ideas that relate to their own lives. • A theme can be: 1. a revelation of human character 2. may be stated briefly or at great length 3. A theme is not the “moral” (lesson) of the story • In some cases, plays are written solely to communicate ideas rather than to portray character or plot realistically. Dramas of ideas, such as political theater or propaganda films, are explicitly written to communicate a message, to educate audiences about an issue, and to change minds. • The most satisfying drama doesn’t take sides because realistic drama is “threedimensional” and characters are complete human beings—not totally “good” or “bad”. The Four Main Types of Drama • • • • Tragedy Comedy Melodrama Farce Tragedy • Tragic drama is one of the most powerful of all dramatic forms. It has captured the imaginations of dramatists from the Greeks to Shakespeare to contemporary playwrights. • There are may definitions of what makes a play a tragedy, but most definitions share at least some common characteristics: 1. Tragic drama deals with profound and universal problems, such as the nature of fate or the meaning of life. It also involves powerful emotions, such as ambition, jealousy, greed, or hate. 2. Tragic drama often centers on a tragic hero who becomes caught in a dramatic conflict that eventually leads to ruin or death. Usually the tragic hero is at least partially responsible for his or her ruin. 3. Some theorists blame the tragic hero’s downfall on a tragic flaw, such as pride or blindness, which contributes to the tragic hero’s own destruction. 4. Despite the fact that the play ends in disaster for the tragic hero, the effect of tragedy on its audience is uplifting rather than depressing (a catharsis— emotional release at the end). Our sympathy for tragic heroes allows us to identify with their situations. The lessons they learn in the tragic ending broaden our own understanding of life, causing us to feel noble emotions such as awe, pity, and compassion. Comedy • Comic drama has traditions that can be traced from the Greeks through modern television comedy. • In contrast to the profound themes of tragedy, comedy deals with smaller, everyday problems (i.e. rivalries, mistaken identities, obstacles to love, and so on). • Comic characters have no tragic flaws. In contrast to tragic heroes, who must end in ruin to learn important lessons, comic heroes do not suffer greatly and always survive, no matter how complicated the situations they face. • The comic conflict always ends more happily than it began. Just as classical tragedy usually ends in ruin and death, classical comedy often concludes symbolically, with a marriage celebration. • In contrast to tragedy, the effect of comedy on the audience is more entertaining than uplifting, but effective comedy can also deepen our understanding or life. Often the comic playwright’s intent is to show us a mirror image of ourselves. By getting us to laugh at humorous characters and situations, they encourage the comic side of being human. Melodrama and Farce Not every play, film, or television drama fits the definition of tragedy or comedy. Often dramas fall into the category of two related dramatic forms: melodrama or farce. Melodrama Melodrama—arouses pity and fear through cruder means. Good and evil are clearly depicted in white and black motifs. Plot is emphasized over character development. The melodramatic plot aims for thrills and theatrical excitement. Many of today’s popular dramatic forms—such as murder mysteries, horror movies, soap operas, and Westerns—fall into the melodrama category. Unlike tragedy, melodramas are very easy to understand. It is very clear who the “heroes” and “villains” are, and how we should feel about them. Farce Farce—aimed at arousing explosive laughter using crude means. Conflicts are violent, practical jokes are common, and the wit is coarse. The plots of farces are often based on complicated situations and frenzied action (i.e. unlikely coincidences, chase scenes, mistaken identity). Farce emphasizes physical humor and rarely springs from “character in action,” the basis of more sophisticated comedy.