Acquired characteristics

advertisement

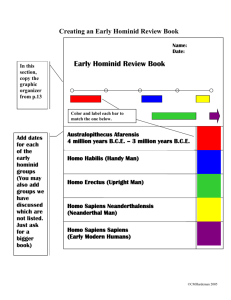

Building Modern Humans In the 1960s, Mary Leakey found tools from about 1.8 million years ago in Olduvai Gorge. These tools, called Olduwan tools, are attributed to Homo habilis. OLDOWAN TOOLS (left to right): end chopper, heavy-duty scraper, spheroid hammer stone (Olduvai Gorge); flake chopper (Gadeb); bone point, horn core tool or digger (Swartkrans). These tools predated finds of Homo habilis himself. In the early 1960s, some pieces of jawbone were found. Eventually, skull fragments surfaced. The brain of H. habilis was about 30% larger than that of Australopithecus, although the skeleton was otherwise similar. The use of tools is significant because of what it implies about mental ability. Archaeologists date the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) from this time. From this point on, hominid evolution is characterized as much by its tools as by anything else. Homo habilis, like its ancestors, was an African homind. FIGURE 15.1 Hominid Relationships Later hominids generally evolved in two directions—one a “robust” line that became extinct about 1 million years ago, and the other the “gracile” line continuing down to modern Homo sapiens (see also figure 14.6). H. Habilis may have developed a larger brain and used it to develop more sophisticated tools. This likely produced a more complex social and hunting system. This idea is called the hunting hypothesis – the idea that the need to kill small animals led to increased mental abilities, group interactions, and aggressive behavior. H. Habilis and the related species H. rudofensis and H. ergaster account for about a million years of hominid evolution from ~ 2.5 mya to ~ 1.5 mya. Homo habilis Homo rudolfensis Homo ergaster The species that followed, Homo erectus, was the first to be found outside of Africa. From the neck down, H. erectus was similar in stature and anatomy to modern humans. Its brain was almost 50% larger than that of H. habilis. Homo erectus camp sites show evidence of many animal bones and many tools. There is also some evidence of fire, although their use of it is uncertain. In the late 19th Century, it was widely believed that a single, direct ancestor could be found linking the apes and the humans. This is not true, but it energized the search for hominid fossils at the time. FIGURE 15.2 “Missing Link” Fallacy (a) A misreading of primate evolution led to the view that midway between modern apes (such as orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees) and modern humans there existed a direct, intermediate ape that was a blend of ape and human traits. (b) As current phylogeny shows, no such direct intermediate occurs, or is expected. Instead, apes and humans trace their ancestry back along independent lineages to a common ancestor about 6 to 7 million years ago (see also figure 14.6). Enter Eugene Dubois. Dubois was a Dutch physician who was interested in hominid fossils. He traveled to Sumatra, largely because he thought at modern-day orangutans provided evidence that the “missing link” might have lived there. Dubois joined the Dutch Army as a physician and was assigned to Sumatra. After becoming ill, he was sent to Java. He searched along the Solo River there, assisted by convict labor provided by the Dutch government. In 1891, they found a skullcap. A year later, a leg bone. He thought he had found the “missing link” which came to be known as “Java Man”. Most of the scientific establishment was skeptical. Other fossils were accumulating. A group of fossils were discovered near Beijing, China (then Peking) in the 1920s. They represented about two dozen individuals. Collectively, they gave a fairly complete reconstruction of “Peking Man”, later to be recognized as Homo erectus. Some content that the African predecessors of the Asian H. erectus represent a different species, Homo ergaster. Others believe the similarities between the two indicate that they are the same species. It appears likely that Homo erectus (or, perhaps, H. ergaster) arose in Africa, then migrated to Asia. They were tall (some reaching 6 feet) with large brains. At this point, body hair was likely reduced. Hunting was central to their existence. FIGURE 15.4 Out of Africa Various species of gracile hominids originated in Africa and then spread to other continents. This figure summarizes the approximate times and geographic locations of hominid species. The Neandertals Neandertals seem to have branched off about 500,000 years ago from the line leading to modern humans. They are descended from Homo heidelbergensis, which was a contemporary of H. erectus and also had an African origin. H. heidelbergensis spread northward and briefly overlapped with the earliest Neadertals. Neanderthal Man Neanderthals were not ancestors of modern man, although they did coexist with modern humans. Neanderthals arose about 300,000 years ago and survived until just 30,000 years ago. Neanderthal man is often classified as a subspecies of modern humans, Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Some workers (including Kardong) prefer to recognize them as a separate species, H. neanderthalensis. Evidence that some Neanderthals buried their dead suggests a more sophisticated culture. And finally, Homo sapiens The most recent evidence suggests that species also has its origins in Africa. In 1997, Tim White and coworkers found the remains of Homo sapiens approximately 160,000 years old in Ethiopia. Tim White By about 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had spread across Asia. At this time, they exhibited tool use and culture very similar to that of the Neanderthals. By about 40,000 years ago, however, H. sapiens had surpassed the Neanderthals in culture. They entered Europe, and by 30,000 years ago the Neanderthals were extinct. Africa Homo erectus (white arrows) originated in Africa but spread to parts of Eastern Asia, and perhaps into Europe. H. neanderthalensis apparently followed much the same migrations out of Africa as did H. sapiens after them. FIGURE 15.11 Replacement of H. erectus by H. sapiens (a) Multiregional Theory proposes that after H. erectus dispersed to various geographic regions, it continued to evolve in place, producing modern humans. (b) The Out-of-Africa Theory proposes that after H. erectus dispersed to various geographic regions, H. sapiens arose in Africa, then also dispersed to other geographic regions, displacing H. erectus as it spread. Current evidence seems to favor the Out-of-Africa theory. How did humans reach the New World? There are several possibilities. The most likely is through Beringia, a land bridge that connected Siberia and Alaska during the Ice Ages. FIGURE 15.12 Human Colonization of the New World The most likely routes were through Beringia via the coastline or inland via a land corridor that opened in the glacial ice sheets. Other, although more speculative, routes include a possible Pacific crossing or an Atlantic crossing. (After Campbell and Loy.) The arrival of humans coincided with the disappearance of many species of large mammals from North America. “Clovis” spearpoints are found associated with early human sites across North America. It is thought that the arrival of sophisticated human hunters led to the extinction of many “naïve” species of native mammals. Other researchers have suggested that the earliest humans in the Americas may have arrived by sea. This would help explain archaeological sites in Chile, which seem too old to have been explained by a Beringia crossing. DNA results have suggested to some workers an earliest entry date of 42,000 years ago, long before the Clovis peoples. The study of skulls has added to the confusion. Some prehistoric Americans had skulls that more closely resemble southern Asians than northern ones. It is possible that humans reached the Americas multiple times, by multiple routes. FIGURE 15.13 Human Variation and Relatedness Based on genetic similarities, the various ethnic groups of humans can be compared for their closest human relationships and nested together accordingly.