Perioperative management of sickle cell disease and trait

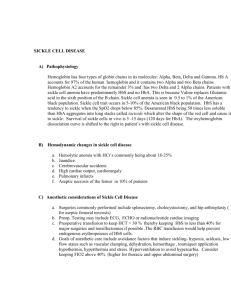

advertisement

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE PATIENTS Ruma Anand Yen-Phan Ta MBBS 3 Dr D Green May 2005 SICKLE CELL SYNDROMES Sickle cell disease (SCD) refers to a group of haemoglobinopathies. HbSS – Sickle cell anaemia HbSC disease HbSD disease HbS/β-thal - Sickle β-thalassaemia Over 10,000 patients with SCD in Britain. Up to 10% afro-caribbeans (AFC) in UK carry the HbS gene (i.e. have sickle cell trait). SCD endemic in parts of North America, Africa, Mediterranean, Middle East and India. Therefore, theoretically all non-caucasian patients should have a sickle screening preoperatively In practice, the test is usually restricted to AFCs MOLECULAR BASIS OF SICKLE CELL DISEASE Normal adult HbA contains 2 α chains and 2 β chains. Homozygous for HbSS – sickle cell anaemia. HbS has valine substituted for glutamine in the 6th position of β-globin chain. HbS becomes insoluble at O2 tension in venous range 5 – 5.5kPa and crystallizes sickling rigid cell wall increased viscosity difficult capillary passage but reforms again in well oxygenated lung .. leads to reduced life span Can cause occlusion and obstruction tissue/organ infarct pain (these are clinical episodes known as crises). HbSC and HbS/β-thal similar symptoms to homozygous HbSS Heterozygote (sickle-trait) often asymptomatic, sickling can occur at very low oxygen tensions (below 3 kPa). SICKLING TRIGGERS Hypoxaemia - isolated HbSS cell sickle at a partial pressure of O2 less than 5.3 kPa. Acidosis Hypothermia Dehydration Low perfusion states Infections SICKLE CELL AND SURGERY Surgery requiring GA may increase risk of vaso-occlusive events in SCD. Sickle cell crises may be precipitated by: Surgical trauma and inflammatory response to tissue injury Hypoxia associated with ventilatory depression (e.g. pain, opioids etc) Dehydration induced by reduced oral fluid intake CLINICAL CRISES There exist three forms of clinical crises in patients with SCD Aplastic crises produce dramatic decreases in erythropoiesis and haematocrit levels. Vaso-occlusive (painful) crises aplastic crises splenic sequestration crises. This is due to parvovirus infection switching off bone marrow RBC production, catastrophic with shortened lifespan of RBC in SCD vs normals (10 vs 120 days) Splenic sequestration crises occur in children younger than 6 years of age. VASO-OCCLUSIVE CRISES Vaso-occlusive crises are characterized by sickling, venous thrombosis, organ infarction, and severe pain Sudden onset of severe pain is usually in bones and joints. Bone marrow ischaemia due to sickling in bone marrow sinusoids. May be precipitated by: Infection Exposure to cold Unusual stress such as trauma, strenuous physical exertion, emotional disturbance Increased haematocrit (due to dehydration) No apparent precipitating factor VASO-OCCLUSIVE CRISES MANAGEMENT Pain may be mild and of short duration but often excruciating and requires hospitalisation. Post-op painful sickle crisis may present, needs to be distinguished from surgical pain. Adequate and prompt pain relief Opioids might be required Can lead to respiratory depression acidosis and hypoxia. Pethidine is avoided due to poor efficacy, short half life and toxic metabolite which may cause convulsions (nor-pethidinic acid) PRE OPERATIVE ASSESSMENT Sickledex: solubility test which screens for HbS. Haematological advice should always be sought for sickle cell anaemia patients. A sample for blood group and antibody screening Does NOT distinguish between trait and disease thus: Haemoglobin electrophoresis is necessary to confirm the exact phenotype. This may take time to perform so a sickle test must be performed well before the time of an elective procedure Previously transfused SCD patients often have red cell antibodies. Evidence of renal, pulmonary or cerebrovascular complications should be assessed pre-operatively. Check for signs of vaso-occlusion, fever, infection and dehydration. CARDIOVASCULAR AND RESPIRATORY MANIFESTATIONS Cardiovascular manifestations result from Risk of pulmonary congestion due to fluid overload during hydration for painful crisis increases with age. Chronic anaemia Pulmonary arterial occlusions leading to cor pulmonale Myocardial damage resulting from small infarcts as well as iron deposition Minority of adult patients will develop problems with fluid balance. Pulmonary dysfunction secondary to upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolization is relatively common in patients with SC disease ACUTE CHEST SYNDROME ACS is typically detected 2–3 days postoperatively. Risk of ACS a factor of 1.7 for every 1g/dl of Hb. Difficult to diagnose but common characteristics: fever, dyspnoea, cough, chest pain and pulmonary infiltrates Pneumonia can trigger and complicate ACS, broadspectrum antibiotics e.g. cephalosporin and erythromycin in combination are indicated if infection occurs. Arterial blood oxygen saturation commonly falls with ACS, therefore monitor arterial blood gases rigorously. MANAGEMENT OF ACS Pre-op to reduce risk of ACS: Transfusion Hydroxyurea Aims to HbS level to ≈30% and haemoglobin >10g/dl before major surgery. The need to reduce HbS to these levels has recently been questioned Enhances formation of HbF Lung function tests to assess respiratory fitness. SKELETAL MANIFESTATIONS Dactylitis (“hand-foot syndrome”) Often 1st manifestation of sickle cell anaemia, predominates in children. Result of necrosis of small tubular bones of hands and feet soft tissue swelling, heat and tenderness over metacarpals and proximal phalanges Need urgent transfusion! In adults the head of femur and humerus are prone to develop infarcts, because collateral circulation is poor. NEUROLOGICAL MANIFESTATIONS Strokes are much more common in children than in adults. Frequently, large arteries such as the internal carotid or the middle cerebral are occluded In adults, haemorrhagic strokes occur more frequently than arterial occlusive strokes Subarachnoid haemorrhages are most common. Exchange transfusion followed by maintenance hypertransfusion is a prudent course of action. Pre-op management for uncovering previous ischaemic injury: Transcranical doppler studies MRI Note proliferative sickle retinopathy due to sickling, stasis and occlusion of small blood vessels. RENAL MANIFESTATIONS Sickle cell nephropathy, characterised by Defective renal concentration and acidification. Lesions are consequence of sickling in vasa recta (supplies blood to collecting ducts, medullary structures etc.) of renal medulla. Concentrating defect results due to obliteration of vasa recta which forms part of the counter-current multiplication system in loops of Henle. Because of the slow blood flow and decreased local oxygen tension, the renal medulla is particularly vulnerable to infarction and necrosis Papillary renal necrosis, 2° to medullary ischaemia, may be manifest by unilateral haematuria. Increased incidence of UTI and pyelonephritis due to structural abnormalities and scarring. RENAL FAILURE Acute renal failure may occur and is commonly associated with dehydration and hypovolaemia. Chronic renal failure is an important cause of illness and death in over 40yr olds with SCD. Dehydration and hypovolaemia must be avoided. PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 1 If anaemia is present and severe, blood transfusion prior to elective surgery may be indicated. transfusion with normal adult hemoglobin (AA) to dilute the sickle erythrocytes and decrease blood viscosity is indicated (see earlier). Maximum Hb 10g dl-1 Use of a tourniquet (depending on surgery planned) is controversial in both the homo- and heterozygote during surgery to prevent stasis of blood. If essential ensure careful wrapping of extremity, normothermia, short compression time, hyperoxygenation. PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 2 Hydroxyurea therapy prior to elective surgery should be considered. Prophylactic antibiotic cover should be considered in view of SCD patient’s increased susceptibility to bacterial infections. Penicillin V or clarithromycin or ciprofloxacin. Pre-operative haematocrit should adjusted to 30-35%, Hb +/- 10g dl-1. be PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 3 Prevent sickling by avoiding Hypoxaemia By measuring oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry and giving prophylactic oxygen. Oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve is shifted to the left. Low arterial saturation in SCD. During surgery and the postoperative period, the inspired oxygen concentration should be increased to around 40% to maintain or increase the arterial oxygen tension. PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 4 Hyperviscosity Keep Hb around 10 gdl-1 Maintain hydration Acidosis Positive pressure ventilation during surgery to achieve normocarbia and avoid acidosis. Aim for mild respiratory alkalosis (pH ≈ 7.45) PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 5 Hypotension, Hypovolaemia and Dehydration Avoided by volume status monitoring by central venous catheter or oesophageal doppler. Depending on duration of procedure and anticipated blood loss. Symptom free heterozygotes require less invasive monitoring and management. To avoid dehydration (i.e. to prevent circulatory stasis) An IV infusion should always be set up preoperatively. Allow oral fluids as late as possible and give pre- and post-operative IV fluids. PERI-OPERATIVE CARE 6 Normothermia maintenance. Fever increases the rate of gel formation by S haemoglobin. Although hypothermia retards gel formation, the decreased temperature also produces peripheral vasoconstriction. Consequently, normothermia is desirable. Increasing ambient temperature in operating room. POST-OPERATIVE Continue careful observation of the patient and monitoring of oxygenation into the postoperative period. Postoperative pain, analgesics, and transient pulmonary dysfunction may decrease arterial oxygen tension. Consequently, supplemental oxygen should be administered after surgery. SUMMARY SCD presents with many acute as well as chronic complications which need to be considered in the pre-op assessment and consequently the appropriate perioperative care provided. Although patients with sickle cell trait (SCT) are at less risk than patients with SCD, the same precautions applied to patients with SCD should also be used for those with SCT.