Black History Month

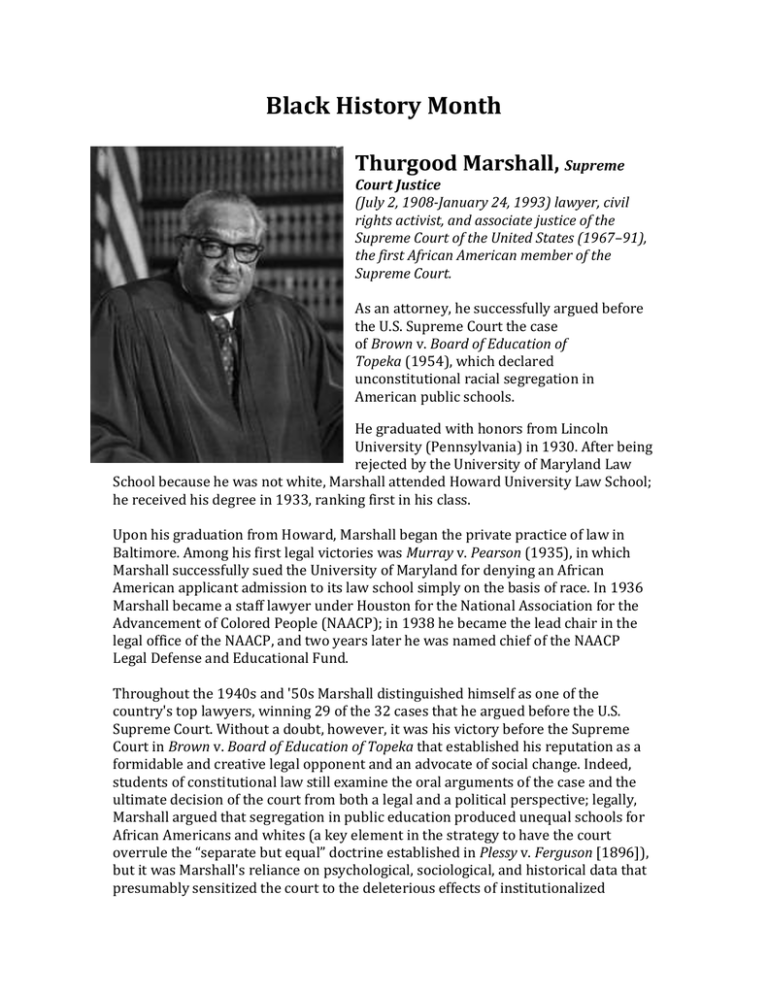

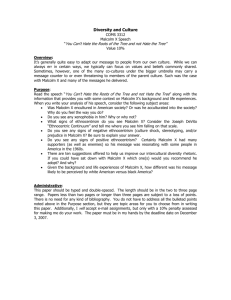

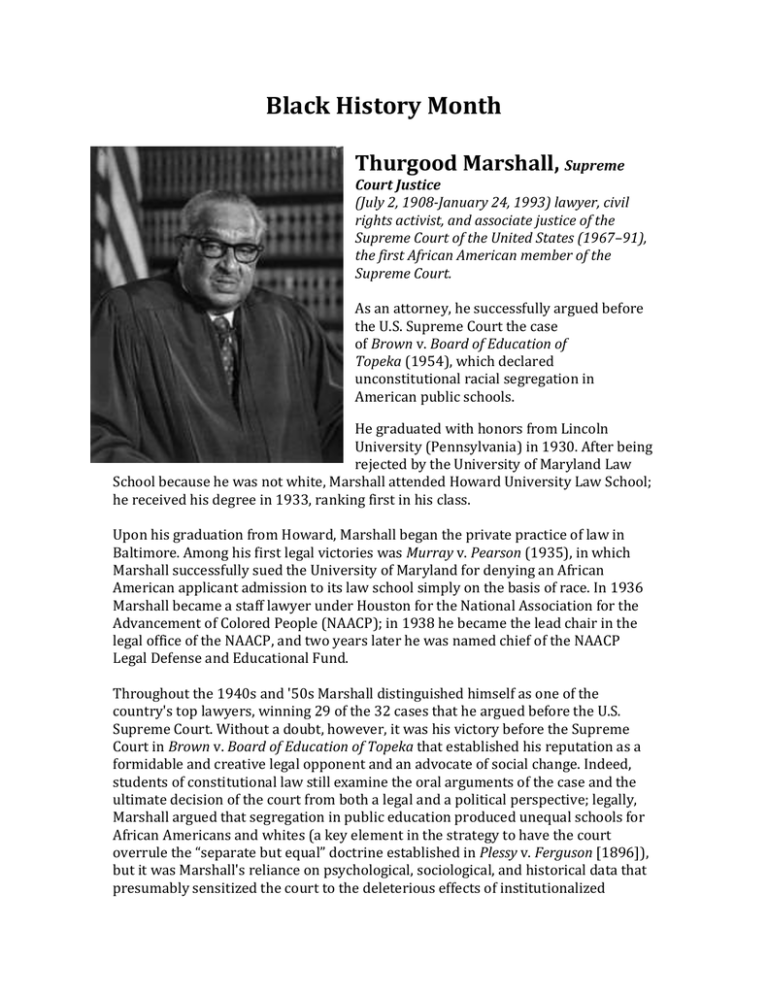

Thurgood Marshall, Supreme

Court Justice

(July 2, 1908-January 24, 1993) lawyer, civil

rights activist, and associate justice of the

Supreme Court of the United States (1967–91),

the first African American member of the

Supreme Court.

As an attorney, he successfully argued before

the U.S. Supreme Court the case

of Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka (1954), which declared

unconstitutional racial segregation in

American public schools.

He graduated with honors from Lincoln

University (Pennsylvania) in 1930. After being

rejected by the University of Maryland Law

School because he was not white, Marshall attended Howard University Law School;

he received his degree in 1933, ranking first in his class.

Upon his graduation from Howard, Marshall began the private practice of law in

Baltimore. Among his first legal victories was Murray v. Pearson (1935), in which

Marshall successfully sued the University of Maryland for denying an African

American applicant admission to its law school simply on the basis of race. In 1936

Marshall became a staff lawyer under Houston for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); in 1938 he became the lead chair in the

legal office of the NAACP, and two years later he was named chief of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

Throughout the 1940s and '50s Marshall distinguished himself as one of the

country's top lawyers, winning 29 of the 32 cases that he argued before the U.S.

Supreme Court. Without a doubt, however, it was his victory before the Supreme

Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that established his reputation as a

formidable and creative legal opponent and an advocate of social change. Indeed,

students of constitutional law still examine the oral arguments of the case and the

ultimate decision of the court from both a legal and a political perspective; legally,

Marshall argued that segregation in public education produced unequal schools for

African Americans and whites (a key element in the strategy to have the court

overrule the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson [1896]),

but it was Marshall's reliance on psychological, sociological, and historical data that

presumably sensitized the court to the deleterious effects of institutionalized

segregation on the self-image, social worth, and social progress of African American

children.

In September 1961 Marshall was nominated to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit by President John F. Kennedy, but opposition from Southern senators

delayed his confirmation for several months. President Lyndon B. Johnson named

Marshall U.S. solicitor general in July 1965 and nominated him to the Supreme Court

on June 13, 1967; Marshall's appointment to the Supreme Court was confirmed by

the U.S. Senate on August 30, 1967.

Copyright © 1994-2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. For more information

visit Britannica.com

Richard and Mildred

Loving, Loving v. Virginia

Richard and Mildred became reluctant

activists in the Civil Rights movement

of the 1960s when they successfully

challenged Virginia's ban on

interracial marriage.

Barred from marrying in their home

state, the couple drove 90 miles north

to Washington, D.C. to tie the knot.

They'd been married just a few weeks,

living in Central Point, when in the

early morning hours of July 11, 1958,

the county sheriff, acting on an

anonymous tip that the Lovings were

in violation of the law, stormed into the couple's bedroom with a pair of deputies.

"Who is this woman you're sleeping with?" the sheriff asked the startled Richard

Loving. Mildred offered up the answer: "I'm his wife." When she pointed out the

couple's marriage certificate hanging on the wall, the sheriff coldly replied, "That's

no good here."

Richard ended up spending a night in jail, the pregnant Mildred several more, and

the couple eventually pleaded guilty to violating Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of

1924, which recognized citizens as "pure white" only if they could claim white

lineage all the way back to 1684. The Lovings' one-year sentences were suspended,

but the plea bargain came with a price: The couple was ordered to leave the state

and not return together for 25 years.

"Almighty God created the races white, white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he

placed them on separate continents," Judge Leon M. Bazile ruled. "And but for the

interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The

fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix."

The Lovings followed orders. They paid their court fees; relocated to Washington,

D.C.; had three children; and only rarely made separate return visits to see friends

and family.

But by 1963, the Lovings decided they'd had enough. The Civil Rights movement

was blossoming into real change in America, and with a sense, perhaps, that this

new era might lead the Lovings back to their old life in Virginia, Mildred wrote

Attorney General Robert Kennedy to ask for his assistance.

Kennedy wrote back and referred the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union

(A.C.L.U.), which took on the couple as clients. The A.C.L.U.'s two lawyers for the

couple, Bernard S. Cohen and Philip J. Hirschkop, appealed the Lovings' case to the

Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. For Richard Loving, the argument to be made

was a simple one: "Tell the court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live

with her in Virginia." When that court upheld the original ruling, the case went to

the United States Supreme Court.

On June 12, 1967, the high court agreed, unanimously coming down in favor of the

Lovings, striking down Virginia's law and allowing and the couple to return home. "I

feel free," Richard is reported to have said after the ruling.

There’s little doubt about Mildred and Richard's legacy. There's an unofficial holiday

celebrating their triumph and multiculturalism, called Loving Day (June 12). More

importantly, the prohibition against mixed race marriages has been stripped out of

every state constitution.

© 2012 A&E Television Networks. All rights reserved.

George Washington

Carver, Chemist and Inventor

An American agricultural chemist,

agronomist, and experimenter, his

development of new products derived

from peanuts (groundnuts), sweet

potatoes, and soybeans helped

revolutionize the agricultural economy

of the South.

Carver was the son of a slave woman owned by Moses Carver. During the Civil War,

slave owners found it difficult to hold slaves in the border state of Missouri, and

Moses Carver therefore sent his slaves, including the young child and his mother, to

Arkansas. After the war, Moses Carver learned that all his former slaves had

disappeared except for a child named George. Frail and sick, the motherless child

was returned to his former master's home and nursed back to health. Though the

Carvers told him he was no longer a slave, he remained on their plantation until he

was about 10 or 12 years old, when he left to acquire an education. He spent some

time wandering about, working with his hands and developing his keen interest in

plants and animals.

By both books and experience, George acquired a fragmentary education while

doing whatever work was available. In his late 20s he finished his high school

education in Minneapolis, Kan., while working as a farmhand. After a university in

Kansas refused to admit him because he was black, Carver matriculated at Simpson

College, Indianola, Iowa, where he studied piano and art, subsequently transferring

to Iowa State Agricultural College, where he received a bachelor's degree in

agricultural science in 1894 and a master of science degree in 1896.

Carver left Iowa for Alabama in the fall of 1896, and accepted a position as Director

of the newly organized department of agriculture at the Tuskegee Normal and

Industrial Institute. Carver devoted his time to research projects aimed at helping

Southern agriculture, demonstrating ways in which farmers could improve their

economic situation.

At this time agriculture in the Deep South was in serious trouble because the singlecrop cultivation of cotton had left the soil of many fields exhausted and worthless.

As a remedy, Carver urged Southern farmers to plant peanuts and soybeans, which

could restore the soil.

Carver found that Alabama's soils were particularly well-suited to growing peanuts

and sweet potatoes, but when the state's farmers began cultivating these crops

instead of cotton, they found little demand for them on the market. In response to

this problem, Carver set about enlarging the commercial possibilities of the peanut

and sweet potato. He ultimately developed 300 derivative products from peanuts—

among them cheese, milk, coffee, flour, ink, dyes, plastics, wood stains, soap,

linoleum, medicinal oils, and cosmetics—and 118 from sweet potatoes, including

flour, vinegar, molasses, rubber, ink, a synthetic rubber, and postage stamp glue.

In 1914, Carver revealed his experiments to the public, and increasing numbers of

the South's farmers began to turn to peanuts, sweet potatoes, and their products for

income. The South became a major new supplier of agricultural products.

When Carver arrived at Tuskegee in 1896, the peanut had not even been recognized

as a crop, but within the next half century it became one of the six leading crops

throughout the United States.

In 1940 Carver donated his life savings to the establishment of the Carver Research

Foundation at Tuskegee for continuing research in agriculture. During World War II

he worked to replace the textile dyes formerly imported from Europe, and in all he

produced dyes of 500 different shades.

Carver was uninterested in the role his image played in the racial politics of the

time. His great desire in later life was simply to serve humanity; and his work, which

began for the sake of the poorest of the black sharecroppers, paved the way for a

better life for the entire South. His efforts brought about a significant advance in

agricultural training in an era when agriculture was the largest single occupation of

Americans, and he extended Tuskegee's influence throughout the South by

encouraging improved farm methods, crop diversification, and soil conservation.

Copyright © 1994-2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. For more information

visit Britannica.com

W.E.B. Du Bois, Activist and

Writer

Du Bois graduated from Fisk University in

1888. He received a Ph.D. in history from

Harvard University in 1895.

Although Du Bois had originally believed that

social science could provide the knowledge to

solve the race problem, he gradually came to

the conclusion that in a climate of strong

racism, social change could be accomplished

only through agitation and protest.

Two years later, in 1905, Du Bois took the

lead in founding the Niagara Movement,

which was dedicated chiefly to attacking the platform of Booker T. Washington. The

small organization, which met annually until 1909, was significant as an ideological

forerunner and direct inspiration for the interracial NAACP (National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People), founded in 1909. Du Bois played a prominent part in

the creation of the NAACP and became the association's director of research and editor of

its magazine, The Crisis.

Du Bois' black nationalism took several forms—the most influential being his pioneering advocacy of PanAfricanism, the belief that all people of African descent had common interests and should work together in

the struggle for their freedom. Du Bois was a leader of the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900

and the architect of four Pan-African Congresses held between 1919 and 1927.

He resigned from the editorship of The Crisis and the NAACP in 1934. Upon leaving the NAACP, he

returned to Atlanta University, where he devoted the next 10 years to teaching and scholarship. In 1940 he

founded the magazine Phylon, Atlanta University's “Review of Race and Culture.” In 1945 he published

the “Preparatory Volume” of a projected encyclopedia of the black, for which he had been appointed editor

in chief. He later returned to a research position at the NAACP. The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois was

published in 1968.

Copyright © 1994-2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. For more information

visit Britannica.com

Ida B. Wells, journalist

Ida B. Wells was born a slave in 1862 in Holly

Springs, Mississippi. Her father, James, was a

carpenter and her mother, Elizabeth, was a

famous cook. Both parents were literate and

taught Ida how to read at a young age. She was

surrounded by political activists and grew up

with a sense of hope about the possibilities of

former slaves within the American society.

Both parents died, along with an infant

brother, during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic

when Ida was 16 years old. At that young age,

she assumed the responsibility of rearing her

five younger brothers and sisters.

She soon became a teacher in order to earn

money for the family and eventually ended up

working in Memphis. While there, one day

changed her life forever. She has accustomed to riding the train in whatever seat she

chose. In 1883, she sued the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad because they forbade

her from sitting in the ladies coach subsequently wrote and article about the

experience. The success of her article about the ease influenced her career change to

journalist.

As injustices against former slaves raged throughout the South and a reign of terror

began, Wells' sense of indignation and quest for justice was fueled. She decided to

use her pen to expose the motives behind the violence. Lynching had become one of

the main tactics in the strategy to terrorize blacks, and exposing its real purpose

became the target of her crusade for justice. When three of her male friends, who

were upstanding, law-abiding, successful businessmen (in direct competition with

white businessmen), were lynched on the pretext of a crime they did not commit,

Wells wrote about the situation with a clarity and forcefulness that riveted the

attention of both blacks and whites. Her major contention that lynchings were a

systematic attempt to subordinate the black community was incendiary.

She advocated for both an economic boycott and a mass exodus. She traveled

through the United States and England, writing and speaking about lynching and the

government's refusal to intervene to stop it. This so enraged her enemies that they

burned her presses, and put a price on her head, threatening her life if she returned

to the South. She remained in exile for almost forty years.

Wells went to Chicago in the mid-1890s where she met and married Ferdinand

Barnett, a widower and a fellow crusader who was a well-known attorney as well as

the founder of The Conservator newspaper. In addition to raising Barnett's two

children from his previous marriage, the couple had four children of their own in

eight years. Even with this added responsibility, Wells continued in her relentless

fight for social justice. She was very active in the suffragist movement and became

one of the founding members of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP) and the National Association for Colored Women (NACW).

Ida B. Wells-Barnett died in 1931, leaving a formidable legacy of undaunted courage

and tenacity in the fight against racism and sexism in America.

Source: www.idabwells.org

Maya Angelou, Author and Activist

Born Marguerite Johnson on April 4, 1928 in St.

Louis, Missouri. Angelou spent her difficult formative

years moving back and forth between her mother's

and grandmother's. At age eight, she was raped by

her mother's boyfriend, who was subsequently killed

by her uncles. The event caused the young girl to go

mute for nearly six years, and her teens and early

twenties were spent as a dancer, filled with isolation

and experimentation.

At 16 she gave birth to a son, Guy, after which she

toured Europe and Africa in the musical Porgy and

Bess. On returning to New York City in the 1960s, she

joined the Harlem Writers Guild and became

involved in black activism. She then spent several

years in Ghana as editor of African Review, where

she began to take her life, her activism and her

writing more seriously.

Maya Angelou's five-volume autobiography commenced with I Know Why the Caged

Bird Sings in 1970. The memoirs chronicle different eras of her life and were met

with critical and popular success. Later books include All God's Children Need

Traveling Shoes (1986) and My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken and Me(1994).

She has published several volumes of verse, including And Still I Rise (1987) and

Complete Collected Poems of Maya Angelou (1995). Her volume of poetry, Just Give

Me a Cool Drink of Water 'Fore I Die (1971), was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

In 1993, Angelou read 'On the Pulse of Morning' at Bill Clinton's Presidential

inauguration, a poem written at his request. It was only the second time a poet had

been asked to read at an inauguration, the first being Robert Frost at the

inauguration of John F. Kennedy. In 2006, Angelou agreed to host a weekly radio

show on XM Satellite Radio's Oprah & Friends channel. She also teaches at Wake

Forest University in North Carolina, where she has a lifetime position as the

Reynolds professor of American studies.

Drawing from her own life experiences, Angelou published Letter to My Daughter in

2008. She wrote the work for the daughter she never had, sharing anecdotes and

offering advice. Well received, the book earned several honors, including a NAACP

Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work-Non-Fiction.

© 2012 A&E Television Networks. All rights reserved.

Langston Hughes, Poet, Novelist,

Playwright, and Columnist

After publishing his first poem, "The Negro Speaks

of Rivers" (1921), he attended Columbia

University (1921), but left after one year to work

on a freighter, traveling to Africa, living in Paris

and Rome, and supporting himself with odd jobs.

After Vachel Linday promoted his poetry, he

attended Lincoln University (1925–9), and while

there he wrote his first book of poems, The Weary

Blues (1926), which launched his career as a

writer.

As one of the founders of the cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance,

he was innovative in his use of jazz rhythms and dialect to depict the life of urban

blacks in his poetry, stories, and plays.

“A Dream Deferred,” by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore-And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over-like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

A prolific writer for four decades, he protested the injustices committed against his

fellow African Americans through his works. Among his most popular creations was

Jesse B Semple, better known as "Simple," a black Everyman featured in the

syndicated column he began in 1942 for the Chicago Defender.

© 2012 A&E Television Networks. All rights reserved.

Shirley Chrisholm, former

Congresswoman

Born Shirley St. Hill on November 30, 1924 in New

York City. Chisholm spent part of her childhood in

Barbados with her grandmother and graduated

from Brooklyn College in 1946.

She began her career as a teacher and earned a

Master's degree in elementary education from

Columbia University. She served as director of the

Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center from 1953 to

1959 as an educational consultant to New York

City's Bureau of Child Welfare from 1959 to 1964.

In 1969, Chisholm became the first black congresswoman and began the first of

seven terms. After initially being assigned to the House Forestry Committee, she

shocked many by demanding reassignment. She was placed on the Veterans' Affairs

Committee, eventually graduating to the Education and Labor Committee. She

became one of the founding members of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1969.

Chisholm became the first African American woman to make a bid to be President of

the United States when she ran for the Democratic nomination in 1972. A champion

of minority education and employment opportunities throughout her tenure in

Congress, Chisholm was also a vocal opponent of the draft.

After leaving Congress in 1983, she taught at Mount Holyoke College and was

popular on the lecture circuit. She is the author of two books, Unbought and

Unbossed (1970) and The Good Fight (1973).

© 2012 A&E Television Networks. All rights reserved.

Coretta Scott King, Activist

Born on April 27, 1927 in Marion, Alabama.

Although best known as the wife of 1960s civil

rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott

King established a distinguished career in

activism in her own right. Working side-by-side

with her husband throughout the 1950s and

1960s, King took part in the Montgomery Bus

Boycott of 1955 and worked to pass the 1964

Civil Rights Act. Her memoir, My Life with Martin

Luther King, Jr., was published n 1969.

Following her husband's assassination in 1968,

she continued their work, founding the Martin

Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, GA. She served as the

center's president and chief executive officer from its inception.

In 1980, a 23-acre site around King's birthplace was designated for use by the King

Center. The following year, a museum complex was dedicated on the site.

King also was behind the fifteen-year fight to have her husband's birthday instituted

as a national holiday — President Ronald Reagan finally signed the bill in 1983.

In 1995, King passed the reins of the King Center over to her son, Dexter, but she

remains in the public eye. She wrote regular articles on social issues and published a

syndicated column. She had been a regular commentator on CNN since 1980. In

1997, she called for a retrial for her husband's alleged assassin, James Earl Ray. Ray

died in prison before the trial could be effected.

Coretta and Martin Luther King, Jr. had four children: Martin Luther King III, who

now serves as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC);

Yolanda, an actress; Bernice, a lawyer and Baptist minister; and Dexter; who runs

the King Library and Archive. King suffered a heart attack and stroke in August

2005; she died on January 30, 2006.

© 2012 A&E Television Networks. All rights reserved.

Malcolm X, Civil Rights Activist

Malcolm X was born as Malcolm Little

on May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, to

Louise and Earl Little. When Malcolm

was four-years-old, his family moved to

East Lansing, MI.

Two years later, in 1931, Earl Little's

dead body was discovered laid out on

the municipal streetcar tracks. Although

Malcolm X's father was very likely

murdered by white supremacists, from

whom he had received frequent death

threats for his involvement in Civil

Rights Activism, the police officially

ruled his death a suicide, thereby

voiding the large life insurance policy he

had purchased in order to provide for

his family in the event of his death.

Malcolm X's mother never recovered

from the shock and grief of her

husband's death. In 1937, she was

committed to a mental institution and Malcolm X left home to live with family

friends.

In 1946, while living in Boston with his half-sister, Malcolm X was sentenced to ten

years in jail on charges of larceny. While in prison, he read extensively and began to

hear about the idea of Black Nationalism – the idea that in order to secure freedom,

justice and equality, black Americans needed to establish their own state entirely

separate from white Americans.

Supported largely by the Nation of Islam, a group his siblings had also recently

joined, Malcolm X converted to the Nation of Islam while in prison, and upon his

release in 1952 he abandoned his surname "Little," which he considered a relic of

slavery, in favor of the surname "X" – a tribute to the unknown name of his African

ancestors.

Now a free man, Malcolm X traveled to Detroit, where he worked with the leader of

the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, to expand the movement's following among

black Americans nationwide.

By the early 1960s, Malcolm X had emerged as a leading voice of a radicalized wing

of the civil rights movement, presenting an alternative to Dr. Martin Luther King's

vision of a racially integrated society achieved by peaceful means. Dr. King was

highly critical of what he viewed as Malcolm X's destructive demagoguery. "I feel

that Malcolm has done himself and our people a great disservice," he said.

In 1963, Malcolm X became deeply disillusioned when he learned that his hero and

mentor had violated many of his own teachings. Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam

in 1964.

That same year, Malcolm X embarked on an extended trip through North Africa and

the Middle East. The journey proved to be both a political and spiritual turning point

in his life. He learned to place the American civil rights movement within the context

of a global anti-colonial struggle, embracing socialism and pan-Africanism.

Malcolm X returned to the United States less angry and more optimistic about the

prospects for peaceful resolution to America's race problems. "The true

brotherhood I had seen had influenced me to recognize that anger can blind human

vision," he said. "America is the first country… that can actually have a bloodless

revolution." Tragically, just as Malcolm X appeared to be embarking on an

ideological transformation with the potential to dramatically alter the course of the

American civil rights movement, he was assassinated.

On the evening of February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where

Malcolm X was about to deliver a speech, three gunmen rushed the stage and shot

him 15 times at point blank range. Malcolm X was pronounced dead on arrival at

Columbia Presbyterian Hospital shortly thereafter. He was 39 years old. The three

men convicted of the assassination of Malcolm X were all members of the Nation of

Islam.

Source: www.biography.com

Charlayne HunterGault, Journalist , Radio

Personality, News Anchor

In 1961 Hunter became the first

African American woman to enroll

in the University of Georgia; she was

also among the first African

American women to graduate from

the university, earning a degree in

journalism in 1963.

After college, she moved to New

York City and worked for The New

Yorker magazine (1963–67) in an

administrative job and contributed

pieces to the “Talk of the Town” section. Many of her articles expressed rich and

realistic portrayals of life in Harlem.

She next joined The New York Times as a staff reporter (1968–77), eventually

becoming the newspaper's Harlem bureau chief. In addition to winning numerous

awards for her coverage of inner-city issues, Hunter-Gault brought about a

significant change in The Times's editorial policy, eventually convincing the editors

to drop their use of the word Negroes when referring to African Americans.

Hunter-Gault gained a national audience after she joined the Public Broadcasting

Service (PBS) news program MacNeil/Lehrer Reportin 1978. When the program

grew into the 60-minute MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour in 1983, she became its national

correspondent and reported on topics that included racism, Vietnam veterans, life

under apartheid, drug abuse, and human rights issues. In 1997 Hunter-Gault left PBS

to become the Africa bureau chief for National Public Radio (NPR), and in 1999 she

was named Johannesburg bureau chief for the Cable News Network (CNN), a post

she held until 2005. She published a memoir, In My Place(1992), and New News Out

of Africa (2006), a book documenting positive developments in Africa. In 2005

Hunter-Gault was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ)

Hall of Fame.

Copyright © 1994-2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. For more information

visit Britannica.com