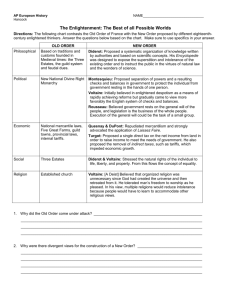

Travel report - University of Warwick

advertisement

Voltaire’s Fragments sur l’Inde and the problematic nature of Indian-European exchange in the later eighteenth century The concepts of ‘interconnected’ or ‘global’ history have made significant inroads into several historical disciplines, including amongst others economic, social, and material history, history of science and the history of consumption. They have not yet, however, significantly impacted on the history of ideas, and are, save for the odd exception, rarely considered in the realm of political economy.1 This paper aims to provide a step towards achieving this by presenting a case study that proves the crucial importance of India in the later eighteenth-century French evaluation of commerce. It is a general consensus amongst scholars of French eighteenth-century political economy to posit a caesura around mid-century, after which a younger generation of lumières, philosophes, or enlightened men of letters were said to have taken over. Some mark it with the publication of Montesquieu’s Esprit des Lois in 1748, some with Rousseau’s first discourse of 1750, and it generally coincides with a period of intensified warfare in Europe and abroad in the guise of the War of the Austrian Succession, the Carnatic Wars, and the Seven Years War. It is usually depicted as marking a transition from a period of general optimism amongst the Enlightened elite about the beneficial powers of commerce and luxury to a more nuanced and sceptical one, or from a period of a theoretical defence of trade and consumption, to a more critical interest in its practical implementation.2 One very prolific writer however, spans both sides of the divide: Voltaire’s first publications on the subject of commerce date from the 1720s, his last from the mid-1770s. His intervention and India’s role within it, will be the subject of this paper. Together with Melon and the young Montesquieu, Voltaire was one of the first authors to propagate the Whiggish defence of commerce in France. Inspired by his stay in England, his contacts with the merchant community there and his readings of Mandeville and the Spectator, he openly extolled luxury and commerce from the 1730s onwards, and his optimism about their beneficial impact explicitly included India on several occasions: see for instance quotes 1 & 2 on the handout. In his increasingly sophisticated defence of luxury and trade he shared the views of several Enlightenment political economists on both sides of the Channel. They can be classed into roughly four interlinked arguments. Firstly, following Mandeville, almost all defenders of luxury adopted his assertion that there can be no clear and stable definition of what constitutes luxury; that it cannot be clearly differentiated from the necessary and is historically relative.3 Secondly, they link commerce to man’s original sociability, so that commerce, sociability, and mutual benefit become inseparable from each other.4 Thirdly commerce is associated with peace, prosperity, and progress, with greater liberty, both political and personal, with urbanity, softer manners, taste, and a general defence of modernity. It is opposed to barbarism, violence, bloodshed, and poverty, and thus, in some writers, especially in Voltaire, becomes almost interchangeable with the concepts of civilisation and Enlightenment.5 Finally, with the advent of the ‘caesura’ or the ‘second generation’, we also see a greater nuancing, in the form of a widely-accepted differentiation between a ‘good’ 1 A notable recent exception is for instance Paul Cheney, Revolutionary Commerce: globalization and the French monarchy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010). 2 Sonenscher, Meysonnier, Shovlin, Clark, Hont 3 See Volt, Melon, Hume also Berry 4 Article forthcoming. 5 Karen O’B, Pomeau (histories) and a ‘bad’ kind of luxury. This is best known in the writings of Hume and in Saint-Lambert’s Encyclopédie article ‘luxe’, but Voltaire also developed this view and, especially in his great histories, the Essai sur les moeurs and the Siècle de Louis XIV, he differentiated between a positive, ‘bourgeois’ type of luxury, and a noxious, ‘feudal’ type. The latter was associated with ostentation and a type of society in which the luxury of the few was paid for by the misery of the masses. The modern kind of luxury however, was associated with private, bourgeois consumption and based on personal enjoyment and good taste. It was seen as giving employment to the masses and therefore leading to general prosperity. It had all the connotations the defenders of luxury praised and that Albert O. Hirschman has summarised as the ‘doux commerce’ thesis: refinement, urbanity, better taste and manners improved by increased sociability and especially the influence of women, and on the international level, peace and co-operation.6 Voltaire’s concept of modern, bourgeois commerce thus became central to his depictions of progress, civilisation, and Enlightenment.7 India figures in these texts, as in quotations one and two on the handout, but it is never central to the argument. There is however one text in which European trade with India is one of the main preoccupations: the Fragments sur l’Inde et sur le général Lally. Written and published in 1773-1774, they bring together, apparently unlinked, remarks on the European powers in India; Indian culture, history, and religions; and a defence of the French general Lally, who, after an unsuccessful campaign in India during the Seven Years War, was brutally executed on trumped-up charges of high treason in 1766. In the text commerce is still depicted as a central and crucial force for change. ‘It is merchants,’ Voltaire writes, ‘who have changed the face of the world.’ However the work also represents a complete rejection of all of the assertions about commerce outlined before, which for decades had been central to Voltaire’s concepts of Enlightenment and civilisation. Whereas before commerce was claimed to promote peace, prosperity and happiness, as well as liberty and thus human dignity, it was now linked to war, carnage and misery. The work opens with the following remarkable passage, marked as quotation three on your handout: As soon as India became a little known to the barbarians of the West and the North, she became the object of her greed, and this became even more marked when these barbarians had become polished and industrious and created new needs for themselves. It is well known that hardly had we left the seas surrounding south and east Africa, we fought twenty Indian nations of whose existence we had only just learnt. The Albuquerques and their successors only managed to bring pepper and cloth to Europe by carnage. Our European nations only discovered America to devastate it and to soak it in blood, in return for which they got cocoa, indigo, and sugar. The condemnation seems an echo of that expressed by the mutilated Negro slave in Candide, who pays the price for the Europeans' enjoyment of sugar. Together with the classic example of sugar, the objects in questions are typical of the international luxury trade at the time. They link the fate of India and the East Indies to that of America and the West Indies in one sweep: at this time most of the cocoa and sugar consumed in Europe came from Central and South America and the West Indies, whilst indigo, spices, pepper in particular, as well as fine fabrics, silks and calicoes, high- 6 Hirschman Cf Berry and Sekora See John Robertson, The Case for the Enlightenment: Scotland and Naples 1680-1760 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), in which he argues that that 'the intellectual coherence of the Enlightenment may still be found [...] in the commitment to understanding and hence to advancing, the causes and conditions of human betterment in this world' (p. 28). He identifies three strands in this endeavour, firstly the attempt to understand and define human nature; secondly, questions of material betterment and political economy, so much so in fact that 'political economy was the key to what the Enlightenment explicitly thought of as 'the progress of society'; and thirdly the study of the progress and development of societies, the process of civilisation (p. 29). 7 quality printed and painted cottons, were imported from India and the East Indies.8 What links all these places is that they suffer so that Europe can enjoy. The stress is not laid on the pleasures and sophistication resulting from luxury, but instead on the pain it causes, on greed and violence. The suffering caused is gratuitous in the double sense. Luxury objects are not gained by commerce but by war, the produce in question is 'bought' by devastation and bloodshed, Europe receives its pleasures without giving back benefits of any form, they obtain them gratuitously. Trade is no longer a ‘heureux échange’ as in the Mondain, it is no longer based on sociable mutuality and mutually beneficial. The injustice is exacerbated by the fact that these are 'nouveaux besoins', they are not necessary for survival, only sought out of greed, which makes the suffering itself gratuitous. Human life and happiness are 'traded in' for trivial consumer goods, the barbarity of which is underlined by the contrast of blood and devastation with sugar and cocoa. The blame for this does not lie with the few 'Albuquerques' of this world, it lies squarely with those who benefit from luxury, either through the profits from selling it, or through desiring and enjoying it (this is quotation four on your handout): ‘Almost all these vast domains, these costly establishments, all these wars undertaken to maintain them, were the fruit of the effeminacy of our cities and the greed of our merchants, even more so than of the ambition of the princes.’. The condemnation falls on the same bourgeois luxury with its traditional links to merchants urbanity, the Mondain’s 'mollesse' which is best translated as effeminacy, which Voltaire had previously extolled. In what seems a complete volte face of Voltaire's earlier position, the merchant no longer contributes to the happiness of the world' as he had done in the Lettres philosophiques. Instead his greed immediately contributes to global misery. Trade now results in war, devastation and enslavement. This is quotation five on your handout: ‘The successors to the brahmins, to these inventors of so many arts, to these lovers and arbiters of peace, have become our manufacturers, our mercenary negotiators. We have devastated their land, doused it in our blood. [...] Our European nations have destroyed one another in this same land to which we only came to look for money, and where the first Greeks only travelled for learning.’ Unlike in the earlier defences of commerce, where it was seen to foster peace, liberty, and the arts and sciences, it is now divorced from all three, indeed directly opposed to them: Luxury and trade, here in the guise of money, are explicitly contrasted to the arts and sciences or progress towards enlightenment, here summarised as ‘learning’. The successors of the bracmanes have to give up the arts and love of peace to accept a position of servitude in commerce, and engaging in commercial activities, which Voltaire had advocated as a certain way to personal independence and development during his English years, had turned into the very opposite. The anti-luxury argument is made most strongly in quotation six on your handout: It’s to furnish the tables of the citizens of Paris, London and other large cities with more spices than used to be eaten at the tables of princes; it’s to decorate simple townswomen with more diamonds than queens used to wear for their coronation; it is constantly to infect one’s nostrils with a disgusting powder, to fill oneself, following one’s fancy, with useless liquids unknown to our forefathers, that an immense commerce has been established [...].We have always complained about taxes, and often most justly so, but we have never considered that the biggest and harshest of all taxes is the one we impose upon ourselves with our new delicacies which have become necessities, and which in reality are ruinous luxury, even if we do not call them luxuries’ Luxury and commerce had been given critical connotations before, in the Essai sur les moeurs for instance, but previously that was always because they were the wrong type of luxury, the ‘bad’, feudal kind, not the beneficial, bourgeois luxury of enjoyment which spread universal opulence. This is not the case here. For the very first time Voltaire attacked the very type of bourgeois, progressive 8 On this see for instance J. H. Parry, Trade and Dominion: The European Oversea Empires in the Eighteenth Century (London: Cardinal, 1974), pp. 59-61, 66-70, 92-100 and 374. luxury which he had extolled for over four decades: the kind that, in the developments outlined in the Essai sur les moeurs and the Siècle de Louis XIV, had passed from the exclusive domain of 'princes' and 'queens' to precisely those 'bourgeois', those ‘townswomen’ and ‘citizens’ mentioned here. And even though some of it, such as jewellery, is perhaps ostentatious luxury, some is clearly the luxury of comfort and enjoyment: condiments, tobacco, tea and coffee, the type that should engender both sensual pleasure, refined taste, and immense commercial activity; just what Voltaire had applauded in the Mondain. Indian commerce is thus highly problematic. Colonial trade, involving slavery and forced labour had not been considered true commerce by Voltaire, and thus, whilst despicable, did not threaten his thought on commerce as civilisation. India however, as an old civilisation, a sovereign power which had traded internationally for centuries, ought to have been an illustration of the benefits of commerce as pointed to in the histories, the Mondain and the Lettres philosophiques. Instead, it nullifies all four arguments that had marked the optimistic thought on commerce: Luxury now exists as its own category and is to be condemned; this condemnation is comprehensive: there is no longer any differentiation between an advantageous and a noxious kind of luxury; commerce is now divorced from mutuality, sociability, peace and liberty; instead of promoting the arts and sciences, civilisation and Enlightenment it is now a force for their opposite: debasement, violence, and barbarity. This utterly destroyed decades of Voltaire’s own arguments about commerce which had made it absolutely central to his view of society, civilisation, and ultimately of ‘Enlightenment’. So the obvious question is why? Why did he threaten his entire edifice of Enlightenment social thought? I would suggest that the answer to this puzzle lies in the very nature of his Enlightenment project; in its focus not only on political economy but also on a genuine cosmopolitanism, or, to put it into contemporary slang, in its ‘globalism’. And to begin to solve the puzzle, the Fragments need to be seen in their historical context. A study of contemporary French writings reveals that Voltaire’s Fragments combine two current debates in later eighteenth-century France, enlarging, however, both their horizons. Contemporaries were preoccupied with the double problem of Indian trade on the one hand, and the link between modern warfare and commerce on the other. In France, there were lively debates about both. However, they were frequently considered as separate and treated from a Eurocentric if not straightforwardly French point of view. The relative novelty of the Fragments consists in their combination and in their extension towards a more cosmopolitan point of view. The first consists of the more nuanced and critical attitude towards commerce and luxury adopted after the above-mentioned caesura of the mid-century. Several distinguished scholars have analysed the increasing French preoccupation with the worrying link between international commerce, state debt, and warfare, which launched an acute desire for reform, especially after France’s dismal performance in the Seven Years War (1756-63). Michael Sonenscher has pointed to the various attempts by French eighteenth-century intellectuals to reconfigure the French and European economy in order to solve the war-debt nexus.9 Like Istvan Hont, John Shovlin has pointed to an increasing preoccupation with patriotism and agrarianism that went hand in hand with a rejection of luxury-based commerce;10 and in his neo-Tocquevillian account, Henry Clark also points out how a more positive view of the British-inspired model of commercial society endorsed by Melon, Voltaire, and the Gournay circle amongst others, came, by the end of the Seven Years War, to be rejected in favour of a more agrarian-based solution to the nation’s need for reform, as advocated by the 9 Sonenscher 10 physiocratic movement amongst others.11 Would-be reformers did indeed seek to recalibrate the French economy and the role of international trade within it, and their preoccupation did, as in Voltaire’s Fragments, often centre on the devastating effect of international warfare, but their focus on this was the regeneration of France, not the situation of either of the two Indies. Traditionally, starting with the abbé de Saint-Pierre’s project for perpetual piece, and the eighteenth-century revival of hopes for a Henry IV-style Grand Design,12 such reform programmes would include solutions, economic or political, for a lasting European peace and balance of powers, but even in those cases, more often than not, the perspective remained firmly Eurocentric. Whilst Voltaire rejected such a nationalist perspective, he came to accept the link between greed, speculation, trade, international rivalry, and warfare, and hence came to be much more critical in his evaluation of both commerce and luxury. In line with contemporary fashion he adopted a much more positive stance towards agriculture and began to style himself a ‘cultivateur’.13 However, there was a second ingredient to the stance espoused in the Fragments. There was another, albeit partly linked, debate raging in France immediately preceding the publication of the Fragments: a debate about French-Indian trade, or to be precise, about the nature and fate of the French East India Company. Again we see Voltaire making use of some of the arguments brought forward there, but again modifying them and expanding them to give them a more cosmopolitan aspect. The French East India Company had become nearly extinct after the Seven Years War and the government considered abolishing its monopoly. To justify this, the then controller general, Maynon d’Inveau, asked the philosophe and economist André Morellet to write a treatise against the monopoly in 1769, which he duly did. The Mémoire sur la situation actuelle de la Compagnie des Indes was written in the tradition of the Gournay circle to which Morellet belonged, and even contained an essay by Gournay himself as an annexe. It provoked myriad responses and contributed to the abolition of the Company’s monopoly in the same year, revealing widespread dissatisfaction with the Company. When Morellet’s intervention came under fire, the physiocrat Dupont de Nemours wrote to support the pro-abolition stance. His Du Commerce et de la Compagnie des Indes which was also published in 1769 argues for France to cease all direct trade with India. Voltaire was a friend of Morellet and applauded the Mémoire which he saw has having justly killed off the company.14 Moreover, despite his general rejection of the Physiocratic movement, Voltaire maintained a friendship with the physiocrat Dupont de Nemours whose views and works he openly admired.15 Of undoubted importance for Voltaire’s Fragments was the clear link they established between company trade and warfare. However, neither Morellet nor Dupont went as far as Voltaire. Both their arguments were about the nature of the trade, in Morellet’s case the fact that it was conducted under a monopoly, in Dupont de Nemours’ that it was conducted directly, whilst he considered it best conducted indirectly by France, suggesting international commerce be best left to trading nations such as Holland who would become the intermediaries for agricultural nations such as France. Neither Dupont nor Morellet ever condemn all European-Indian trade as Voltaire had done. Instead they considered it as bringing legitimate enjoyments to Europeans and as beneficial to both parties involved, both having a mutual need of it.16 11 12 On this see for instance Sonenscher 13 14 Q Letters Copy in Library, annotations. 15 16 Morellet P. 186 Q, Dupont P. 20 Like perhaps only Raynal’s Histoire des deux Indes and unlike any of the above, Voltaire adopted a genuinely cosmopolitan point of view. He took the arguments about the link between international trade and warfare from the first debate and combined it with the analysis of the French-Indian trade brought forward in the debate about the French East India Company. Voltaire, however, moved away from a Eurocentric focus. If the effect of international commerce was war, it was no use to build up France to a position to win those wars, be it through agriculturalism or through other means, as the French reformist thinkers hoped to do. If another region, in this case India, would suffer from international commerce, this commerce would remain immoral. Voltaire rejected a patriotic point of view – if trade with India benefitted France it was to be continued – in favour of a genuinely cosmopolitan or Enlightened one: if trade was harmful to either party it was in contravention of the principles of mutuality, peace, and progress of civilisation that should mark true commerce. Regardless of whether the injured party was one’s patrie or not, such trade must be condemned. The role of India in Voltaire’s philosophy of commerce thus proves two arguments at once. John Robertson’s case about the centrality of political economy to the Enlightenment project, and Karen O’Brien’s argument about the strongly cosmopolitan character of the Enlightenment.17 As such Voltaire’s Fragments sur l’Inde demonstrate the importance of a ‘global’ or indeed ‘interconnected’ approach to the study of the history of ideas in general and of political economy in particular. 17