How to Prepare for and Give an Effective Oral Argument

advertisement

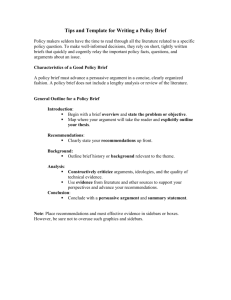

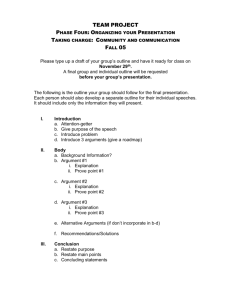

How to Prepare for and Give an Effective Oral Argument Professor Schack Prepared for: Appellate In-House Competition Oral Argument "[O]ral argument — the chance to make a difference in result — is extremely valuable to litigants. If oral argument is to be more than an empty ritual, it must provide the litigants with an opportunity to persuade those who will actually decide an appeal." Moles v Regents of Univ. of Cal., 32 C3d 867, 872, 187 CR 557 (1982). Rules of Professional Conduct 3.3 (a) A lawyer shall not knowingly: (1) Make a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal; *** (3) Fail to disclose to the tribunal legal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel[.] ADMISSION TO PRACTICE RULE 5 I solemnly declare . . . I will employ for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to me only those means consistent with truth and honor. I will never seek to mislead the judge or jury by any artifice or false statement. Audience and Purpose Your audience is a panel of judges. concerned with doing justice on the facts of the particular case. Your purpose is to educate and persuade. But oral argument is not a reiteration or reading of your brief. You are present to engage in a dialogue with the court about the law and your case. Do not read your argument! (Court Rules) RAP 11.4(g) (g) Reading at Length. Counsel should avoid reading at length from briefs, records, or authorities. FRAP 34(c) – Order and Content of Arguments Counsel must not read at length from briefs, records, or authorities. Supreme Court Rule 28(1): Oral argument read from a prepared text is not favored Supreme Court Rule 352(c) specifically prohibits reading "at length from the record, briefs, or authorities." Guide for Counsel in cases to be argued before the United States Supreme Court: Under no circumstances should you read your argument from a prepared script. Twin Pillars of an Effective Oral Argument Balance being in control with being flexible! The pitfalls of wanting too much control: Tendency to become the speech maker or off-the-cuff commentator The lawyer bent on delivering a carefully drafted speech is quickly disconcerted by interruptions and questions that take the advocate off message. The spontaneous commentator, despite his quiz-show ingenuity, spars with the bench but fails to guide the discussion to any discernible goal. The pitfalls of wanting to be overly flexible: The lawyer depend on questions to organize their argument. What does this mean for the advocate? (Objectives) Execute your Strategy: Be able to simplify a complex so that the judge cantoand understand Strategy: Select winthe decide Prepared: Know the facts ofcalibrated your law. Goal:arguments Know what you case want. Flexible –argument Questions are opportunities Respond: toinopposing counsel’s points and to the your assertions and support for those assertions onBe the order which you will argue your issues able to answer the judge’s questions and use the exchange between opposing counsel and the court. and present your arguments. questions to make the points that you want to make or use the question to segue back into your argumen Be able to adjust your arguments to the points raised by the court and opposing counsel. Oral Arguments are Focused Appellate arguments are sharply focused The clock permits no other approach. In contrast to the brief, the oral argument has a narrower focus. Allocate your time so that you will be able to make the arguments. Plan on having half the time to make your argument and half the time to answer questions . Have a plan B in anticipation of a “cold” court. Preparing Your Argument Have an outline, not a prepared text. Less is more. Have an opening prepared (but don’t read it during your argument). Your opening should include: ID yourself and your client Reserve rebuttal (if appellant) Your legal theory Your theme Issues and relief requested – stated affirmatively Your roadmap A word about the “legal theory” and “theme”: Legal theory: Why you are legally entitled to win. Theme: Why you are morally entitled to win. ARGUMENT Ground your argument in the law Standard of review As in your brief, state the law and your facts in a favorable light. Use the rules and cases to make your argument. For example, “Your Honor, the statement that the alleged assailants were members of a gang will prejudice Mr. Simmons because it is likely to evoke an emotional response, not a rational decision, from the jurors ...“ Use a principle-based positive assertion to move into the discussion of a case. For example, “Your Honor, where, as here, statements were made in the face of an ongoing emergency, they are non-testimonial and, thus, admissible without running afoul of the Confrontation Clause. [Then, discuss analogous case] Have a closing, including your request for relief, prepared. Anticipate the court’s questions. Where are the potential weaknesses in your argument? In your opponent’s? Answering Questions Questions from the court tell you what the court is thinking and tell you where the court needs clarification. The court may ask questions for information for clarification on a point to understand your position to test the merits of your case You should welcome questions as an opportunity to address the court’s concerns and to engage in a dialogue with the court. Listen to the questions. What is it that the judge is concerned about? A.K.A.: THE CALL OF THE QUESTION When you answer a question, normally give a short answer and then give a more developed response. Answer with “yes” or “no” when appropriate. Answer with “yes, except when” or “no, when” if the answer is not absolute. Use dovetailing by taking phrases from the question and inserting them into your answer. Don’t back into your answer. Avoid stream of consciousness answers. Never talk over the court. When the court asks a question, stop talking. Answer the question. Do not say that you will get to it later. After you answer the question, segue back into your argument (or, better yet, use the answer to make your argument). And do not make the answer tougher than it is—some questions really are “softballs.” Questions you can expect to be asked What is the standard of review? What is your bottom line – exactly what do you want the court to do Do you concede that . . . ? Conceding facts vs. legal argument – be careful. What is your authority? (questions about precedent) If we think ______, do you lose? (case-dispositve questions) RESPONSIVENESS What does this mean for the Petitioner/Appellant? What does this mean for the Respondent? The Basics The moving party sits on the left as you face the court. When the judge enters the courtroom, rise. Remain standing until the judge sits down. You may then sit down. When the judge is ready, he or she will “call” the case. When asked if you are ready, stand and say, “Yes, Your Honor. The State/Defendant is ready.” Then the State’s counsel should move to the podium. The Basics (cont’d) Avoid distracting mannerisms. Listen carefully to the proceedings: to what opposing counsel is arguing and to the court’s questions and concerns. Watch your time. End when your time is up (or before). If you run out of time, say “thank you” and sit down or ask if you can briefly conclude (and do so). End strong! Speak with conviction. Know what you want, and be able to express it clearly and succinctly. Avoid throat clearing language: “I think” and “I believe.” The Basics (cont’d) Stand when you are addressed by the court. Address the court as “Your Honor,” “this Court,” or by title and last name, such as “Judge Jones.” Be respectful to the court, court personnel, opposing counsel, and the parties. Make eye contact. Use a conversational tone and speak in short sentences. Address the court, not opposing counsel. Dress and act professionally.